Art & Illustration

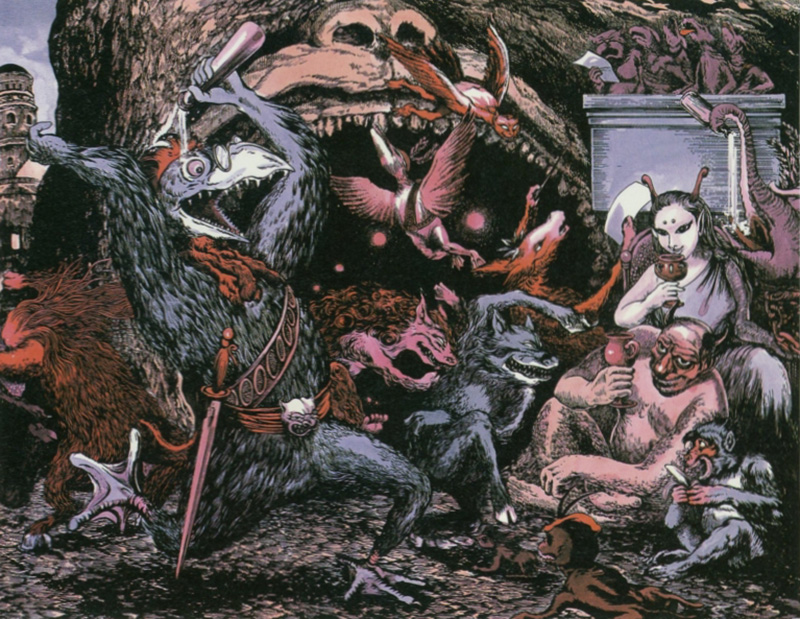

dragonspiritblog: Art by Dragolisco

mighty-dragons: Dark Alliance - Icewind by akreon

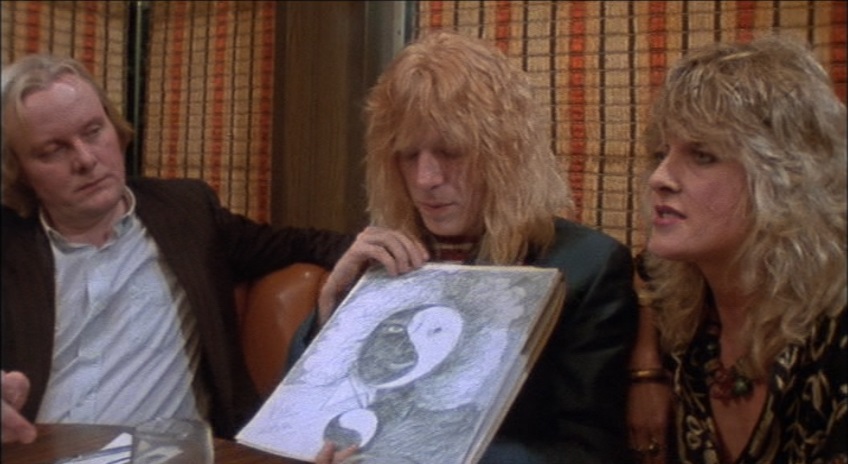

“Have a Good Time All the Time”: ‘This Is Spinal Tap’ and the Art of Longing

Lisa Fernandes / November 7, 2022

1984’s This Is Spinal Tap is all about the pining—epic pining, as high and fulsome as the band’s hair and the wailing notes they (try to) hit. Every single member of the band and their entourage is longing after something they want, something they need, but the real world thwarts them with a passionate glee. They’re either too recalcitrant to claim what they need, assuming that if they keep plowing on as they have been, glory will return to them; or, when their heart’s desire finally falls into their lap like a willing groupie, they’re completely unprepared for the responsibility of the task at hand.

Nobody in the band is content with how things are going, except for perhaps bassist Derek Smalls (Harry Shearer), whose storyline—which originally contained divorce-based angst—was generally abandoned to the cutting room floor, and Viv Savage (David Kaff), who seems to require nothing more than a good time and a keyboard to be happy. Lead singer David St. Hubbins (Michael McKean) longs for the respect the band once earned, and if he can’t be seen as a purveyor of popular music, he at least wants to be enrobed in the sort of dignity that most elder statesmen of rock are afforded. His wife on the astral plane, Jeanine Pettibone (June Chadwick), longs to prove that she has the skill and smarts to manage the band and isn’t just an astrologically-obsessed groupie who happened to get lucky with the lead singer. Manager Ian Faith (Tony Hendra) wants someone, anyone, to respect his authority and listen to what he has to say as chaos unspools around him. And newbie drummer Mick Shrimpton (R.J. Parnell), one in a long line of ill-fated skin-pounders who have lived and died by Spinal Tap’s ethos, just wants to make it through the tour without spontaneously combusting.

At the center of the movie—occasionally apoplectic, mostly filled with a cool and detached sense of calm—stands lead guitarist Nigel Tufnel (Christopher Guest). His longing is the most ardent of them all: he’s nearly visibly boiling beneath his skin with an obvious and ardent desire for the rest of the world to disappear and leave him alone with David.

This Is Spinal Tap has undergone multiple queer readings over the years, one of the very first suggested by Roger Ebert himself, who, in his Great Movies review of the film, declares that Nigel “longs for St. Hubbins with big wet spaniel eyes.” The movie’s cast is definitely aware of this interpretation of events. During a live-streamed 2020 reunion to benefit Pennsylvania’s Democratic party, McKean declared that someone once told him that This Is Spinal Tap is “the world’s greatest love story,” a statement McKean seemed to agree with and find flattering.

The film is also a story of watchful envy. It’s hard to ignore the look in Nigel’s eyes as he watches David, who is watching Jeanine, who is watching the stars. When Jeanine shows up in the middle of the tour and David races off to hug her, the camera lingers on Nigel’s downtrodden face as they hold each other. Later in the film, when Nigel enters the room with his Japanese tour trump card, the frame takes in Jeanine’s fury and disappointment. The tables turn in Nigel’s favor, firmly and utterly. The triangle cannot remain neatly balanced: Jeanine may have David’s body, but Nigel has captured his heart.

David’s physical affection for Nigel shows up in various moments in the film—most notably in the way he jollies Nigel into the room so he can hear a local radio station playing their early hit “Cups and Cakes.” There’s more proof in the pudding of the deleted scenes. Nigel teases David about “Nino Bidungo,” a sailor David had an affair with when the two shared an apartment; the two of them play “All the Way Home,” a skiffle-esque tune and their first composition, as a way to apologize to each other for the vicious fight they’ve just had. With David’s fingers dancing along the fretboard and Nigel plucking away at the strings, there’s a sense of harmony and affection, and the look on David’s face says it all.

Jeanine’s story would be a pitiable one were she not her own worst enemy, so hungry for power that she forces Ian out of his managerial role so that she can run things. It’s possible that she’s looking for control here because she never sees David and—in excised scenes from the film—he is not faithful to her while he’s on the road. If she runs his career and holds his purse strings, then he’ll have to respect her and she’ll be able to keep an eye on him. And in the meantime she can get onstage and bang a tambourine for a few minutes—after all, Linda Eastman got started the same way. But in Jeanine’s case the situation is actually sort of tragic, and just as emotionally provoking as David and Nigel’s unspoken love. The trouble with Jeanine’s attempt at climbing the band’s social ladder is, naturally, that she’s even worse than Ian is at booking the band into suitable venues. Working via astrology and David’s star charts, shoving him out front and letting him indulge his worst tendencies, her machinations are ultimately so clumsy that they result in Spinal Tap playing an amusement park where they’re billed second to a puppet show. What Jeanine longs for—David’s respect—she will never get. She’s left on the sidelines with nothing to be proud of, her influence on the band completely wiped away, longing for somebody to give her attention. But David’s attention remains fixed on Nigel’s face—perhaps forever.

In the very center of this push-pull triangle stands Ian, who just wants the band to get through the tour intact without any further disasters blowing the entire enterprise apart. Once upon a time, one assumes, he sat in some towering office complex, managing the careers of hard-rocking bands that were successful if not famous: a B-grade Led Zeppelin, an off-market Journey. Whatever led him to the door of this down-at-heel rock band, Ian is determined to at least gain some respect from these kids. But the band could care less about respecting him, and he takes his frustration out on inanimate objects. It’s not that the members of Spinal Tap set out to embarrass their fearless managerial forces; it’s that inept staff members, out of pocket creative decisions, and poorly operating stage props embarrass him, staining and straining the tour.

All of this tension is paid off by an orgasmic on-stage reunion and triumphant Japanese tour, which Jeanine can only watch from the sidelines as Ian smugly keeps an eye on her, tapping his cricket bat against his palm. The film chronicles a long, muddy battle for the band’s soul, and Nigel undeniably wins. Yet it’s not a sexist victory; while rock ‘n’ roll and brotherhood win the day, none of this is due to Ian developing a sudden ability to direct the band successfully. While Jeanine might be a bad manager and a worse girlfriend, the film’s other female characters—Bobbi Fleckman (Fran Drescher) and Polly Deutsch (Anjelica Huston)—are shown to be smart about their individual talents and the music business at large: they exist to point up the fact that Ian’s managerial skills are fairly terrible. What they want is for Ian to act like a sensible person.

Spinal Tap goes through a long conga line of humiliations before receiving its Japanese rebirth. While most of the movie’s characters get exactly what they need out of the long, strange trip they take to overseas stardom, some are left with their noses pressed against the plate glass window. But as the Rolling Stones famously sang: “You can’t always get what you want/But if you try sometime you’ll find/You get what you need.”

![]() Lisa Fernandes has been writing since she could talk. Her bylines include Newsweek; Women Write About Comics; Smart Bitches, Trashy Books; and All About Romance.

Lisa Fernandes has been writing since she could talk. Her bylines include Newsweek; Women Write About Comics; Smart Bitches, Trashy Books; and All About Romance.

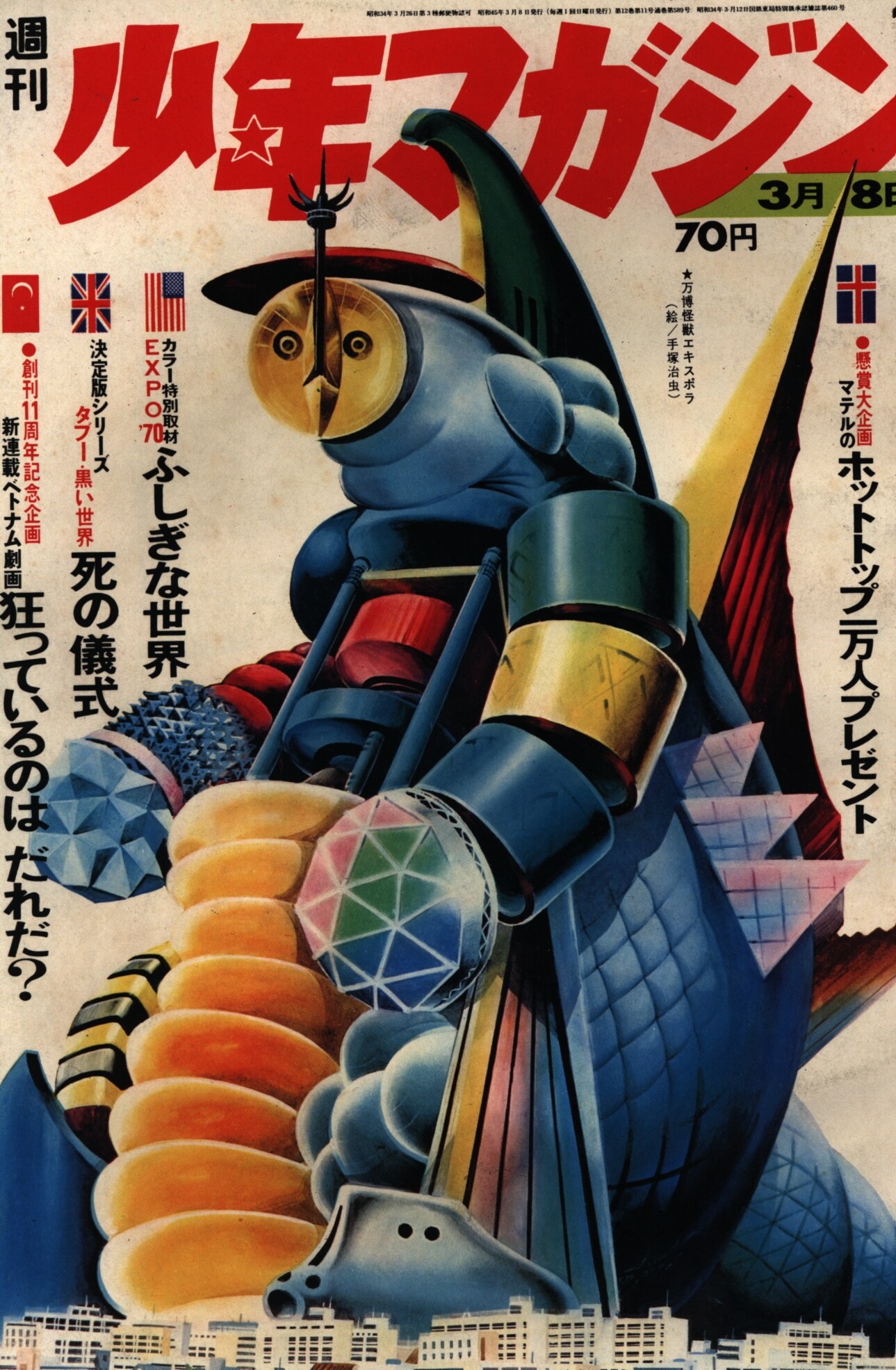

“One Nite Only”: When Frank Zappa Played at State U

James Higgins / September 26, 2022

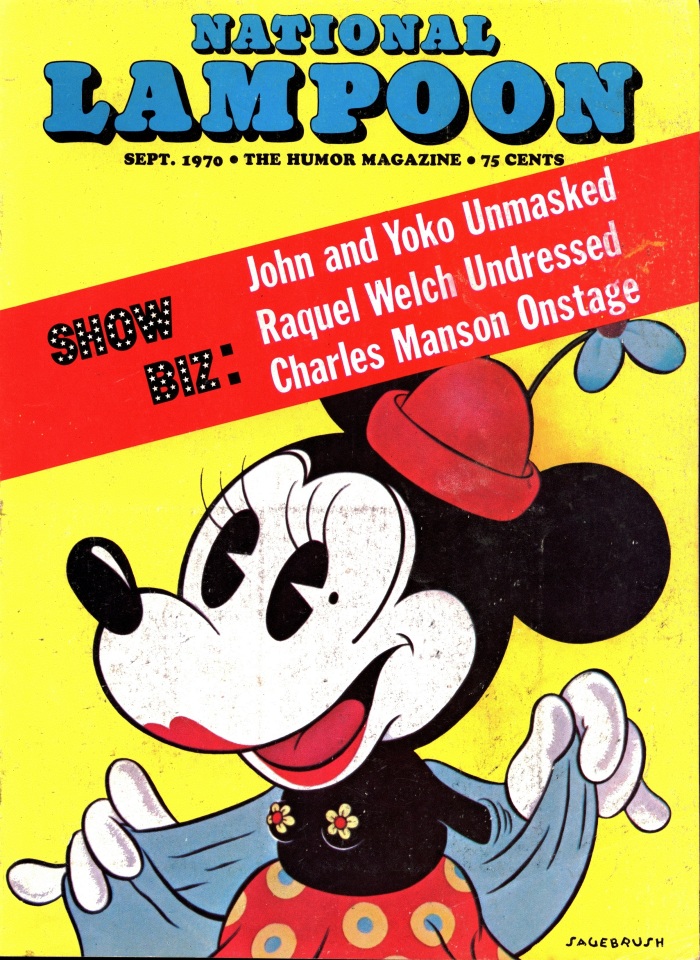

In the summer of 1970, the launch of the humor magazine National Lampoon was not going well. In his memoir of his time as publisher of the Lampoon, Matty Simmons observed that the first six months of the magazine’s existence were troubled ones: “By the fifth issue, the magazine was floundering. It was funny but haphazard. Circulation, after a first issue [i.e., March 1970] sale of 225,000, was now lingering around the 175,000 mark. Advertising was minimal. But some interesting things were happening.” (To put these numbers in perspective, Esquire‘s monthly circulation rate in summer 1970 was nearly 1.2 million.)

Those interesting things included increasing orders from college bookstores, a signal that the magazine was gaining popularity with young people. Dissatisfied with what he felt was artwork that failed to make the magazine stand out on newsstands, Simmons took charge of the cover for the September 1970 issue, commissioning Sagebrush Studios to create a garish red-and-yellow color scheme that promised (among other things) “Raquel Welch Undressed.” The cover showcased Minnie Mouse in disarray: “Minnie flashed tiny little titties covered somewhat discreetly by flowery pasties.”

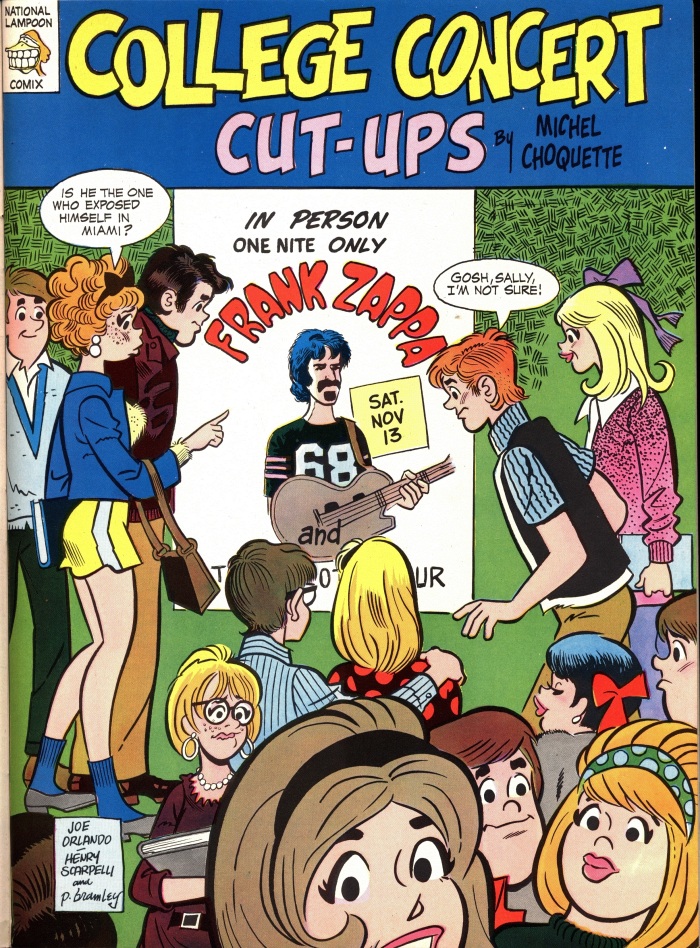

Two days after the September issue went on sale, Walt Disney sued the Lampoon for $8 million (eventually dropping the suit in exchange for a promise by the magazine to never again misappropriate Disney characters). But the September issue was a turning point, as circulation thereafter began to rise. A standout feature was “College Concert Cut-Ups,” a parody of Archie Comics created by Michel Choquette, a Canadian from Montreal who ultimately would spend three years at the magazine and contribute some of its most celebrated comic book parodies.

32-years-old in 1970, Choquette was knowledgeable about the rock ‘n’ roll music scene, including one of the most idiosyncratic bands then performing, Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention. In 1970, the group released two albums, Burnt Weeny Sandwich and Weasels Ripped My Flesh. Both relied on freeform, avant-garde-flavored compositions that were the antithesis of the songs then appearing on the Top 40 singles charts. Along with poking fun at the idea of wholesome, Midwestern college kids being subjected to Zappa’s anything-goes approach to music (and life), “College Concert” found humor in the vagaries of life on the road for a rock band, a theme that Zappa was to cover in-depth in his 1971 movie 200 Motels.

The lead artist for “College Concert” was Joe Orlando, a veteran of the comic book industry who, in 1985, would be made the Vice President of DC Comics. Assisting with the art was Henry Scarpelli, who in fact went on to work for Archie Comic Publications, and Peter Bramley, the Lampoon’s Art Director.

Alas, there is no record of what Zappa thought of “College Concert,” but he must have liked it to some degree, as he contributed to Choquette’s comic book history of the 1960s, the Someday Funnies (which, unfortunately, didn’t see print until 2011).

![]() James Higgins grew up in upstate New York and, like many baby boomers, thrived on a steady diet of sci-fi, fantasy, and horror content in movies, TV, and print media. Now retired, he devotes his days to excavating and examining pop culture artifacts from the Cold War era, both to generate nostalgia among his peers and to ensure that newer generations of young minds are themselves irreparably warped.

James Higgins grew up in upstate New York and, like many baby boomers, thrived on a steady diet of sci-fi, fantasy, and horror content in movies, TV, and print media. Now retired, he devotes his days to excavating and examining pop culture artifacts from the Cold War era, both to generate nostalgia among his peers and to ensure that newer generations of young minds are themselves irreparably warped.

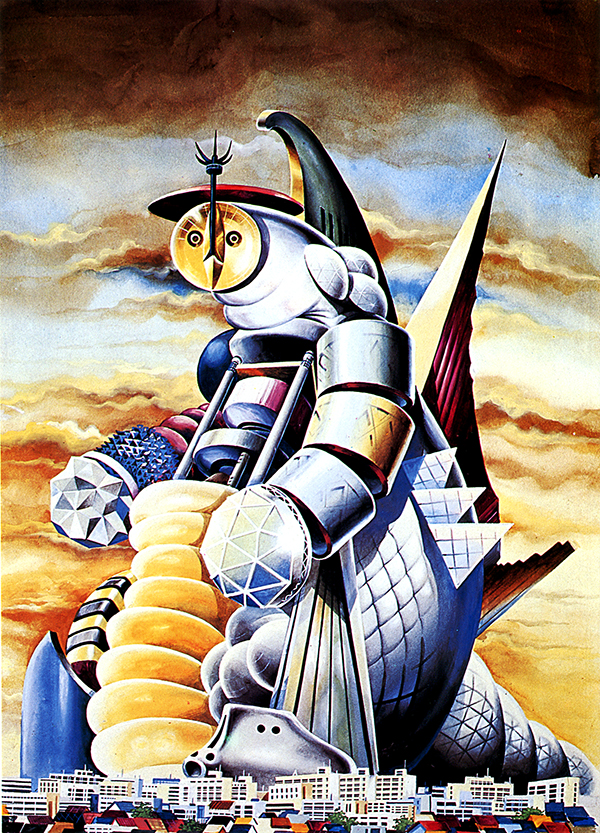

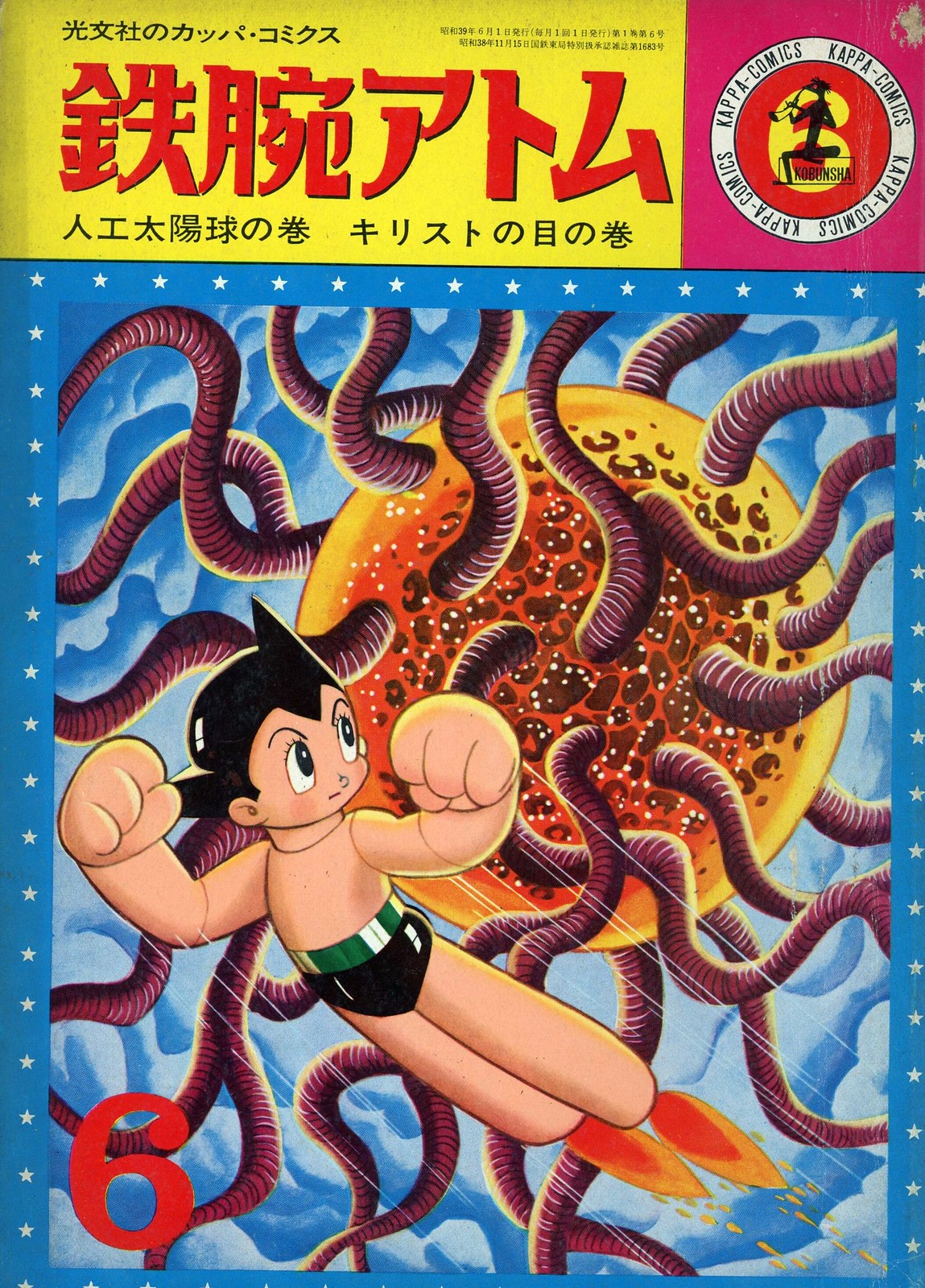

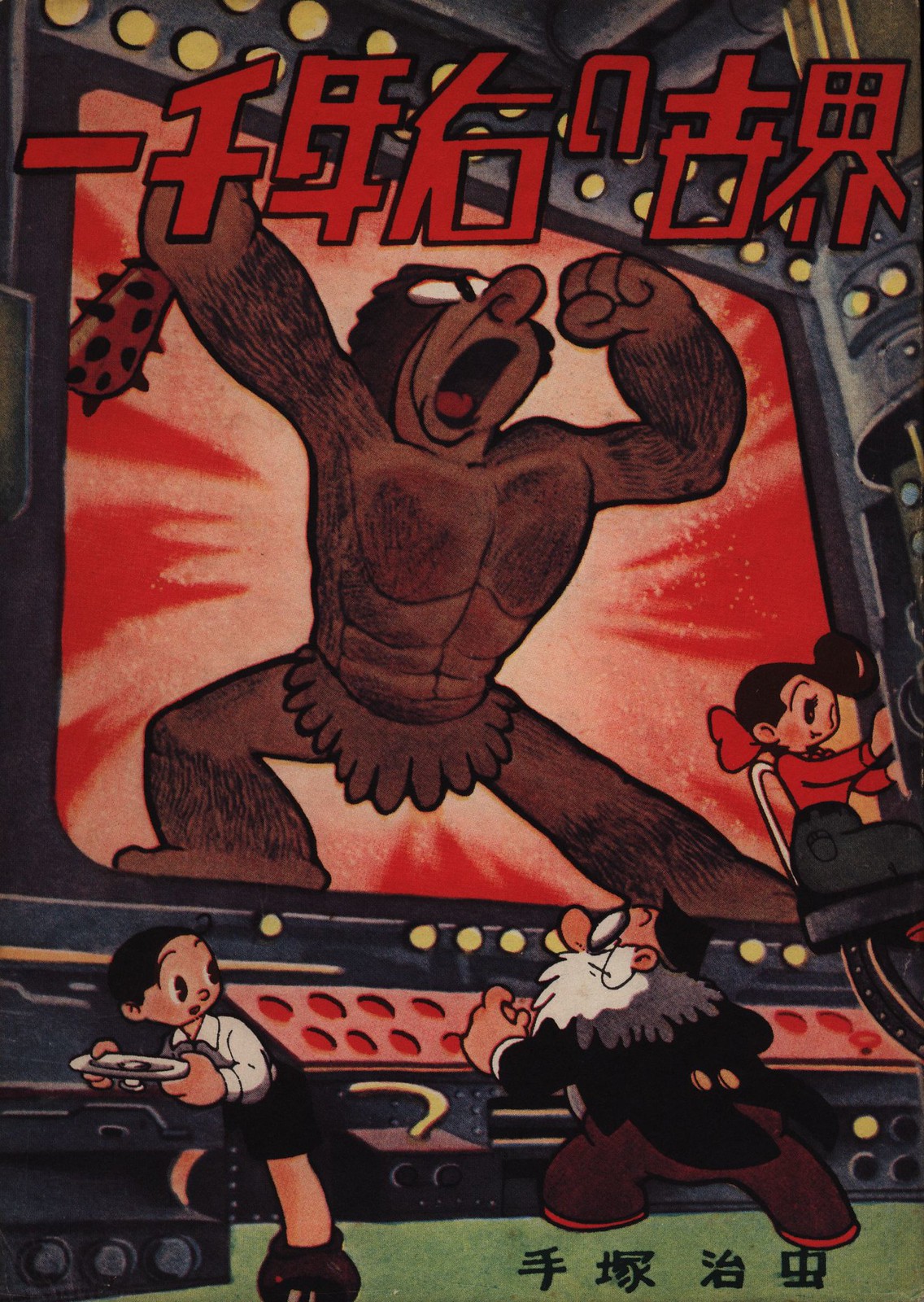

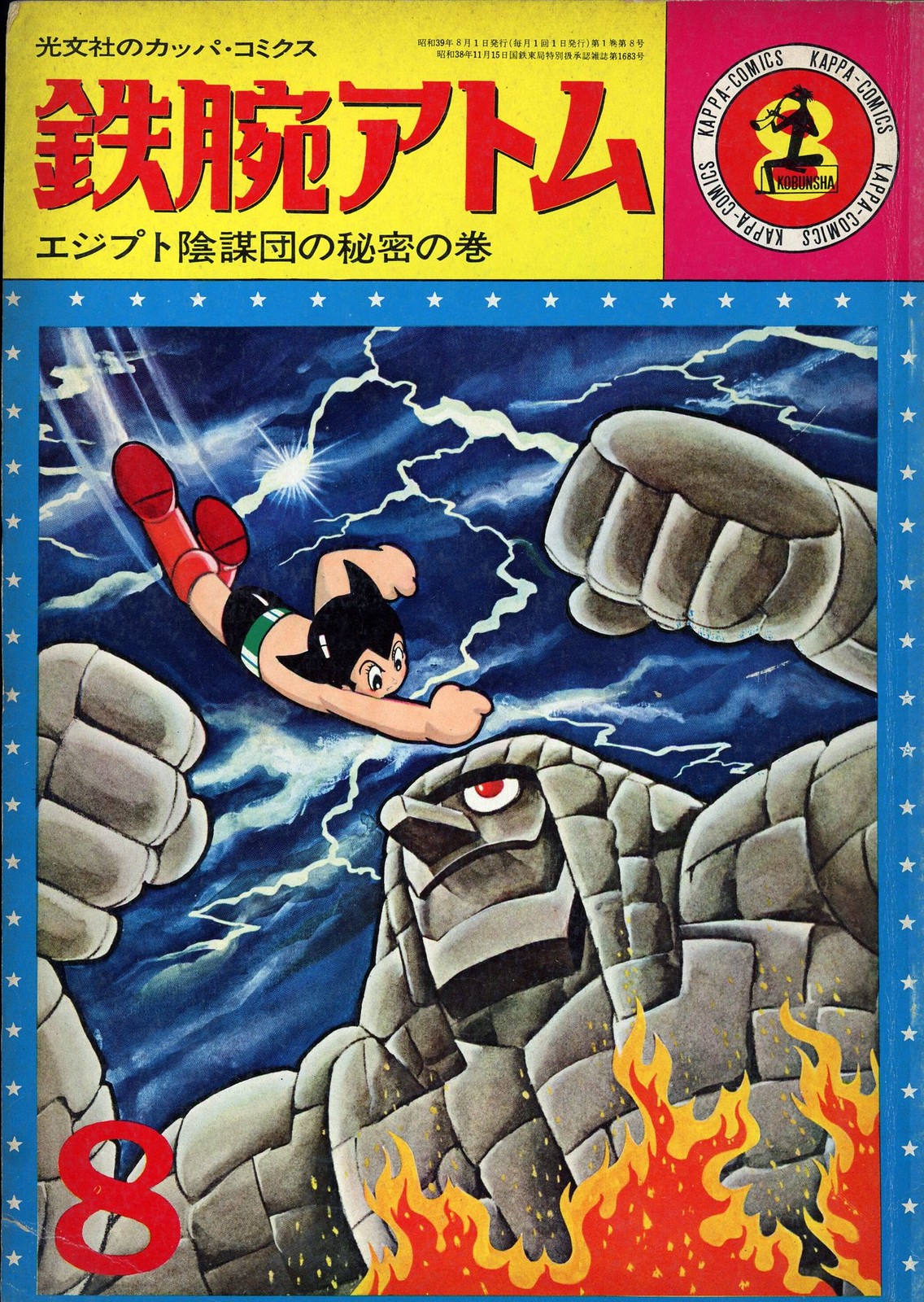

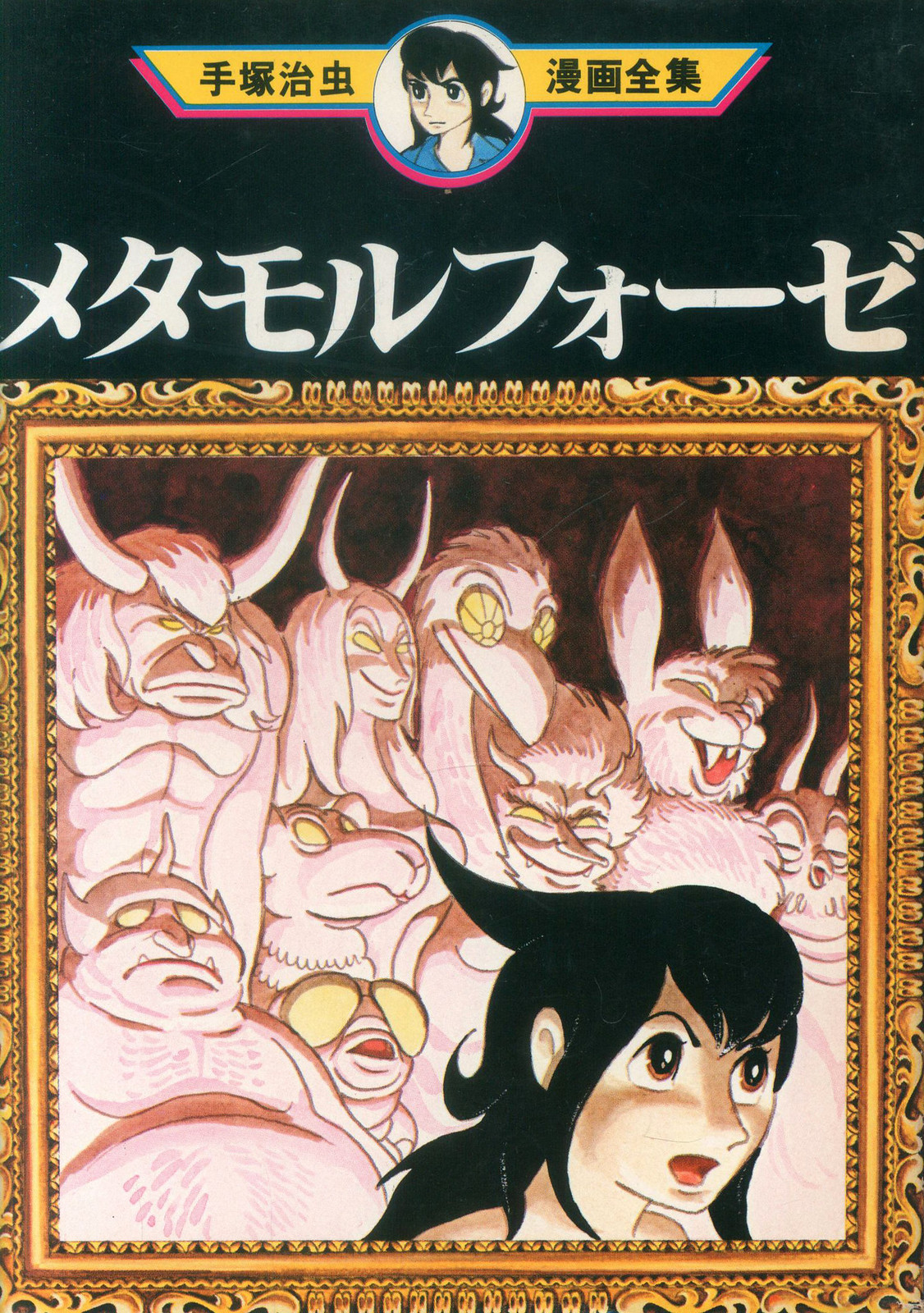

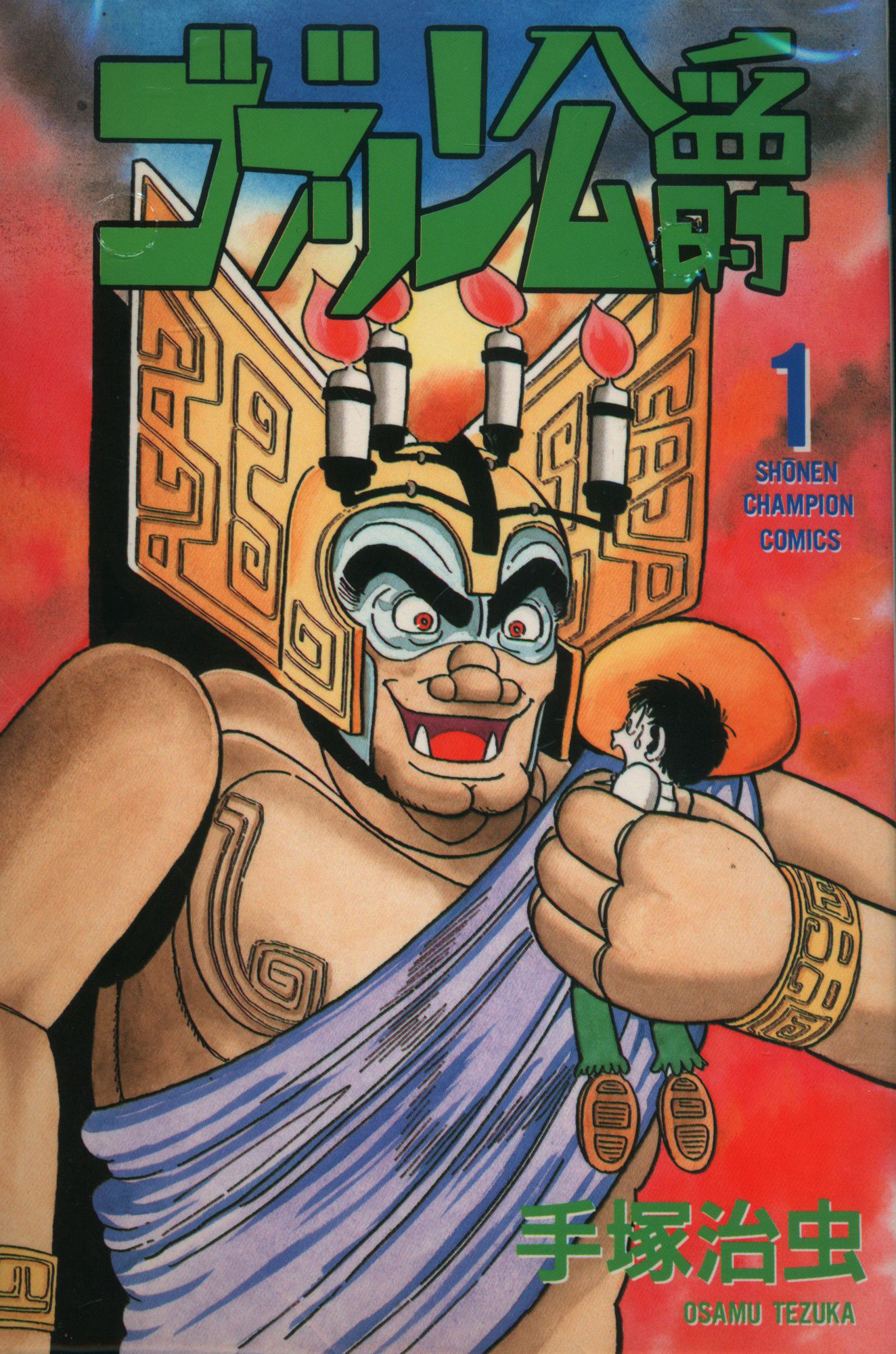

Osamu Tezuka (1928 - 1989)

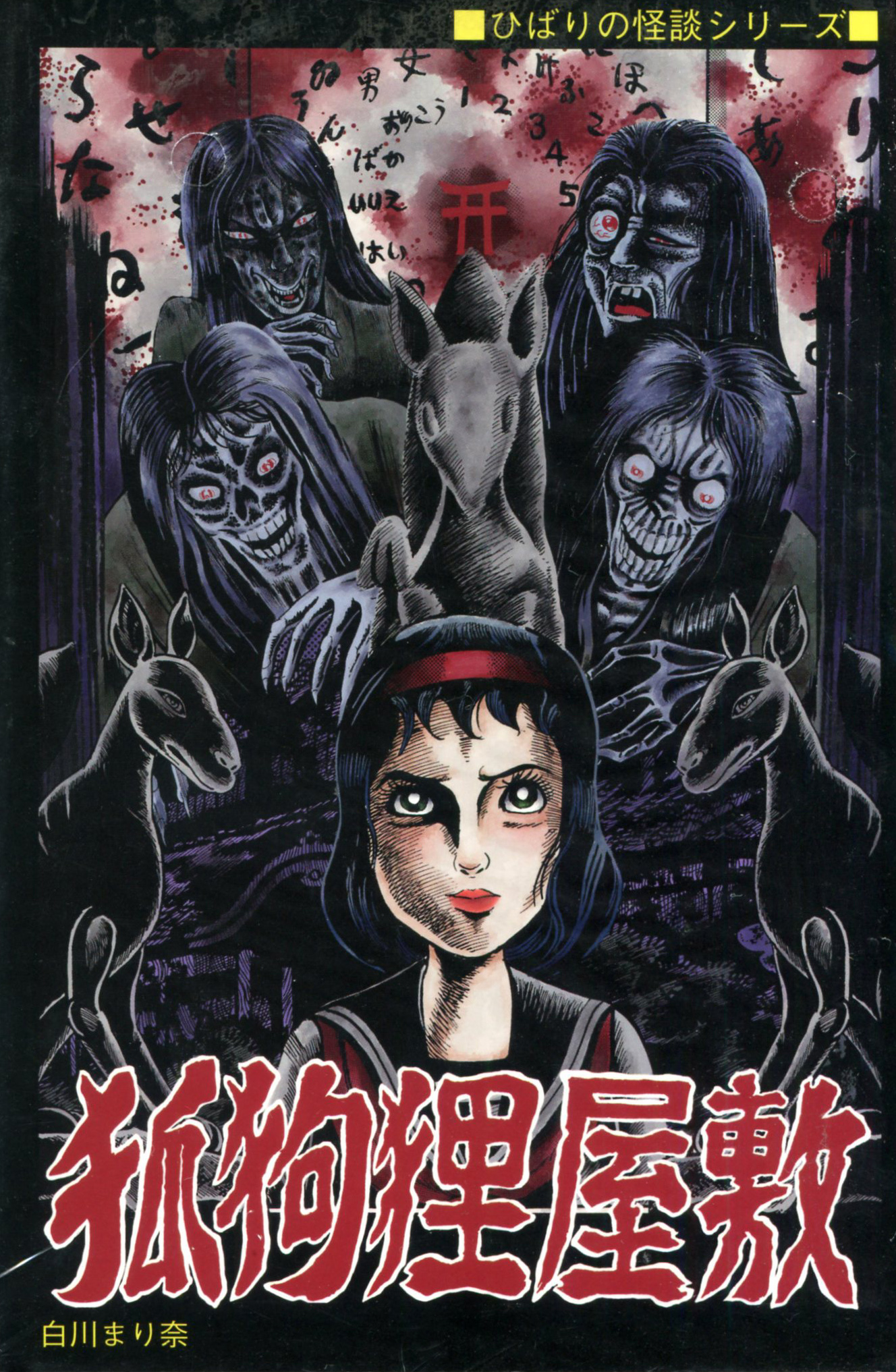

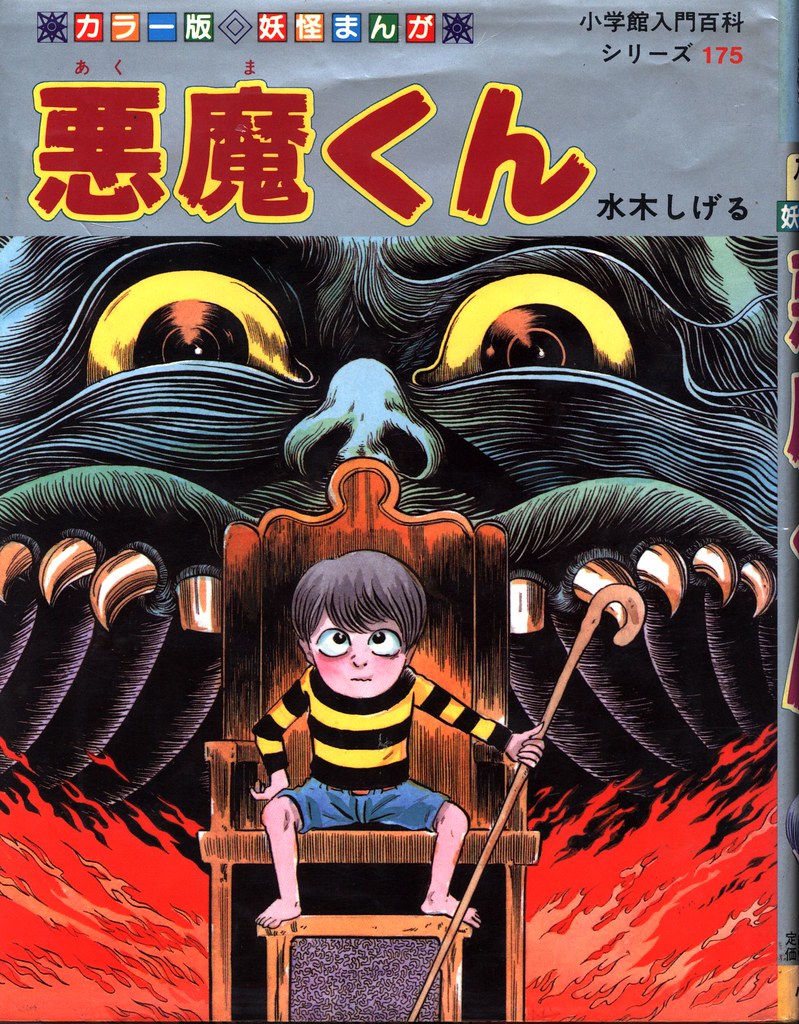

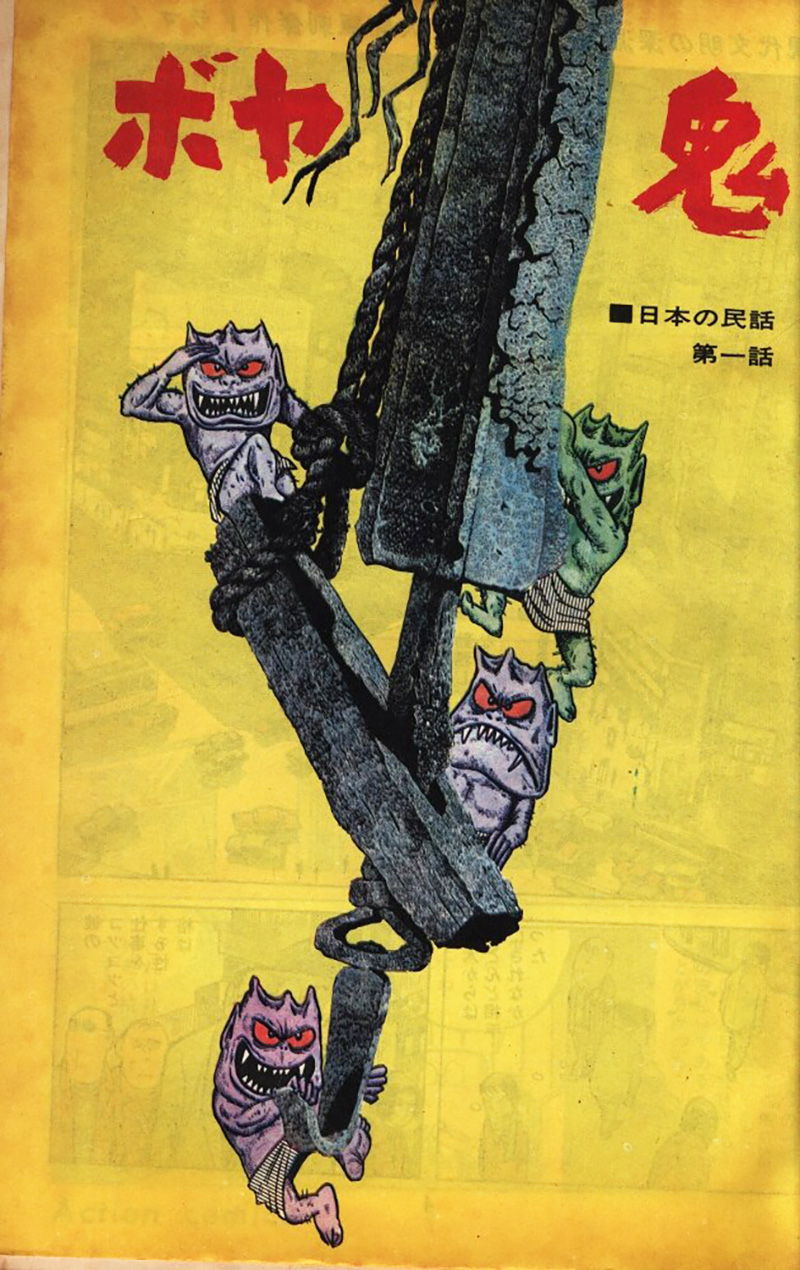

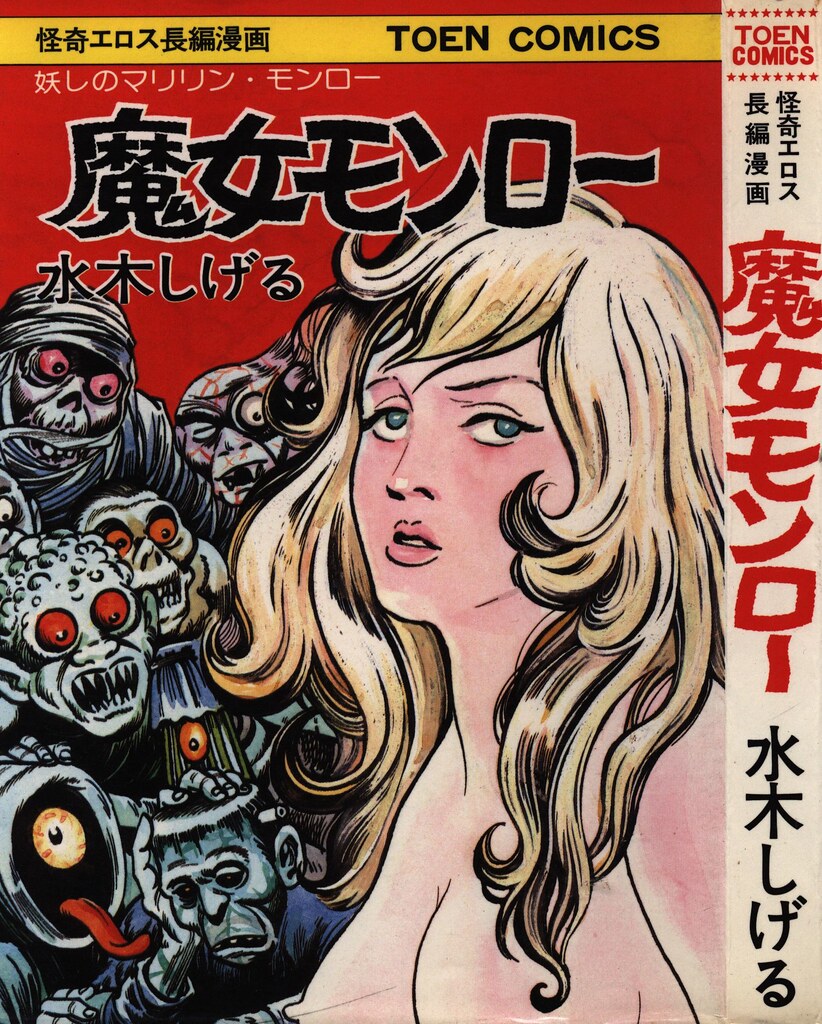

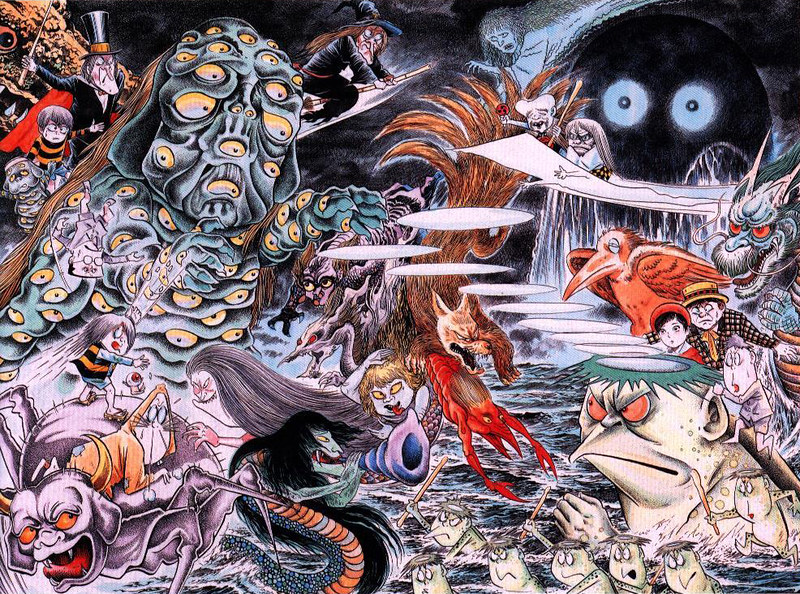

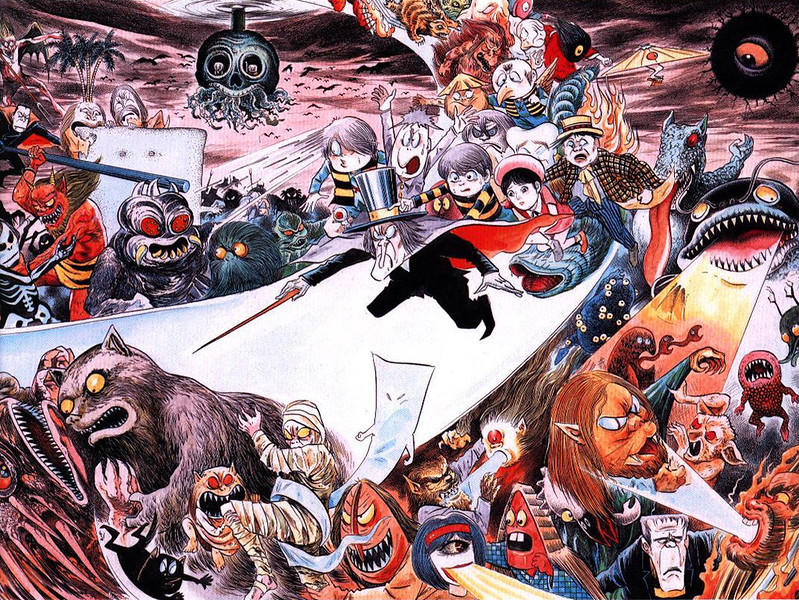

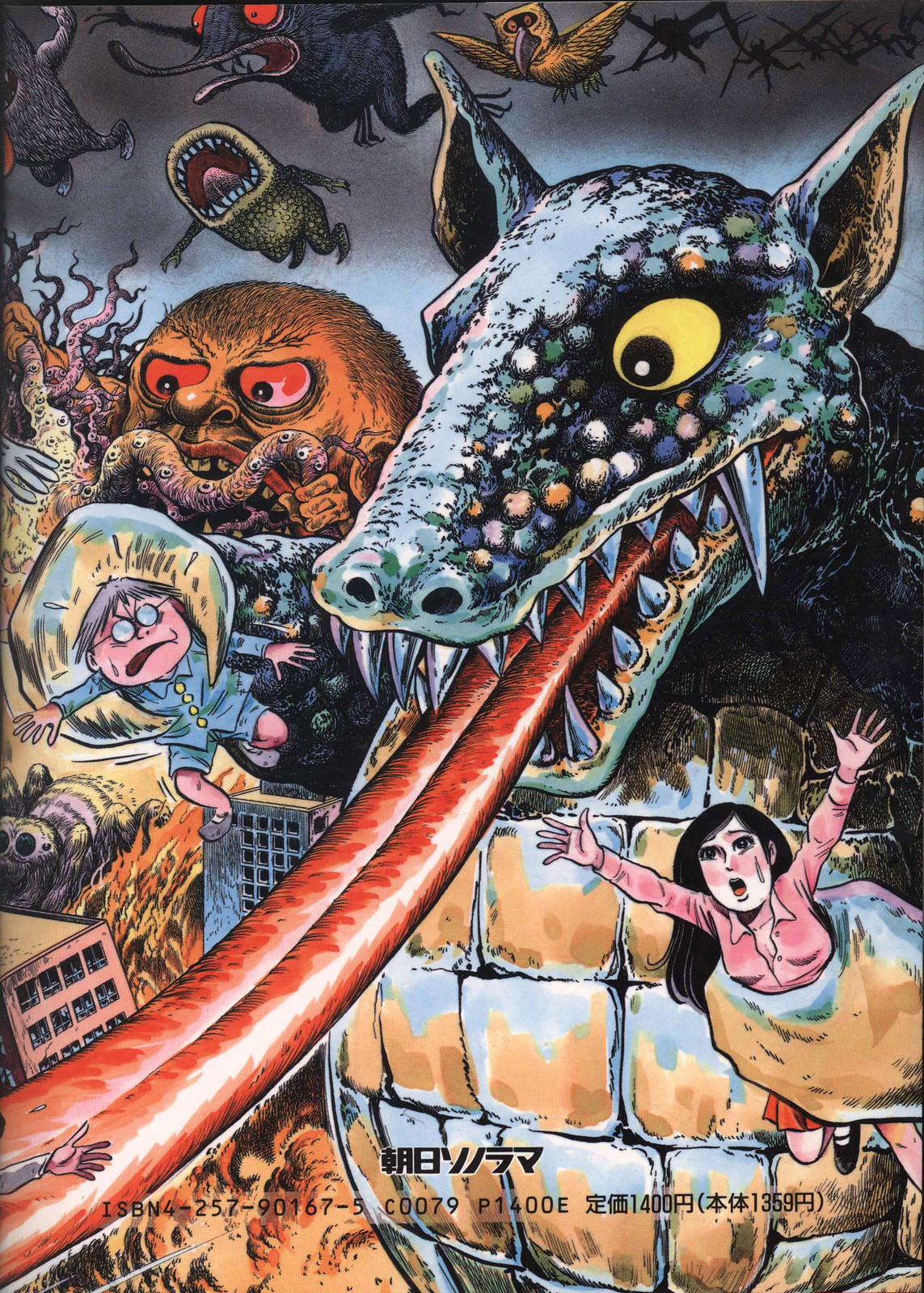

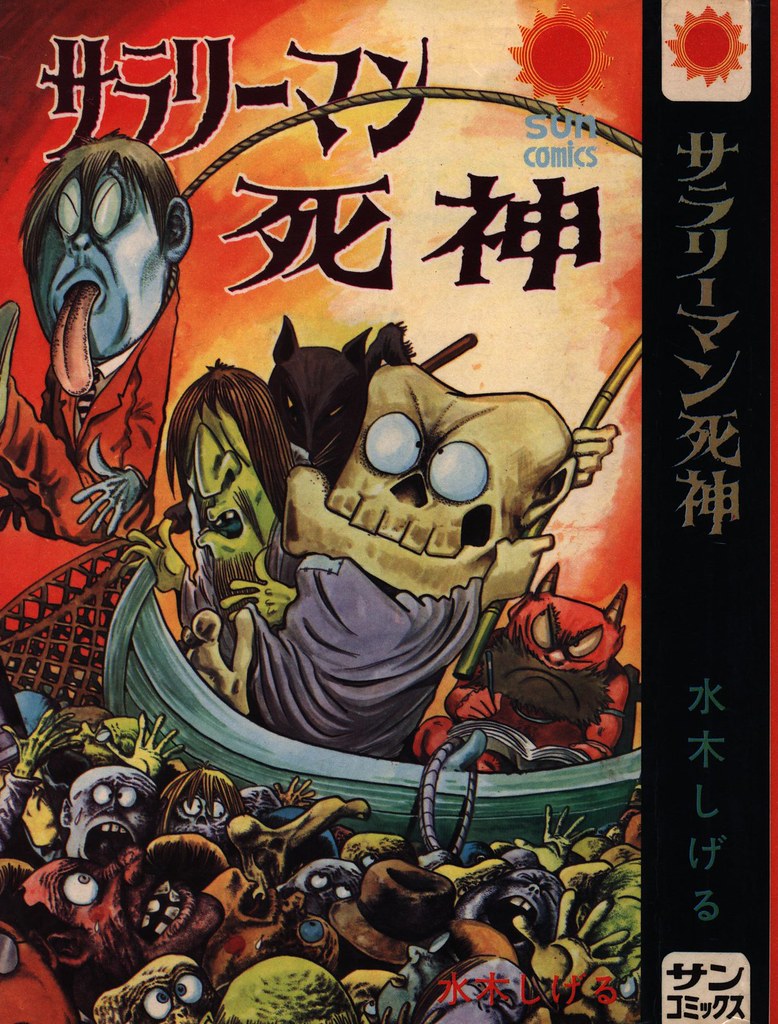

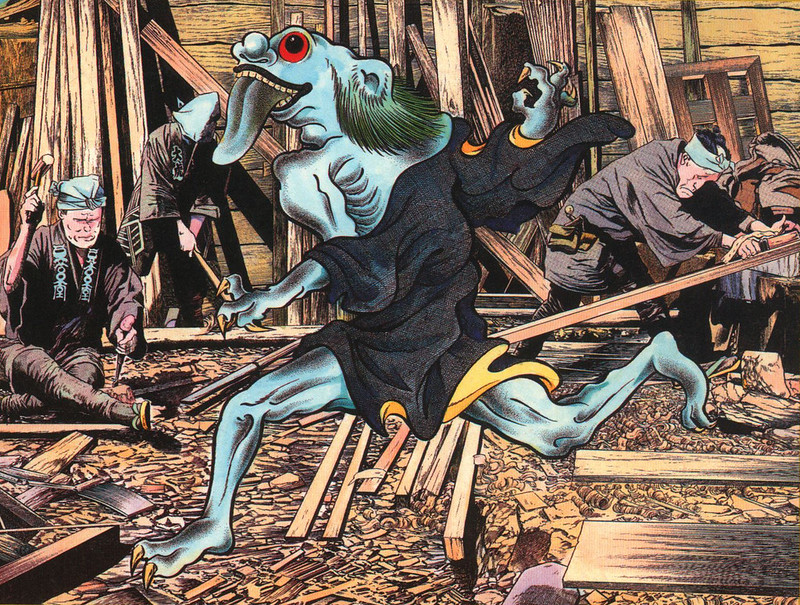

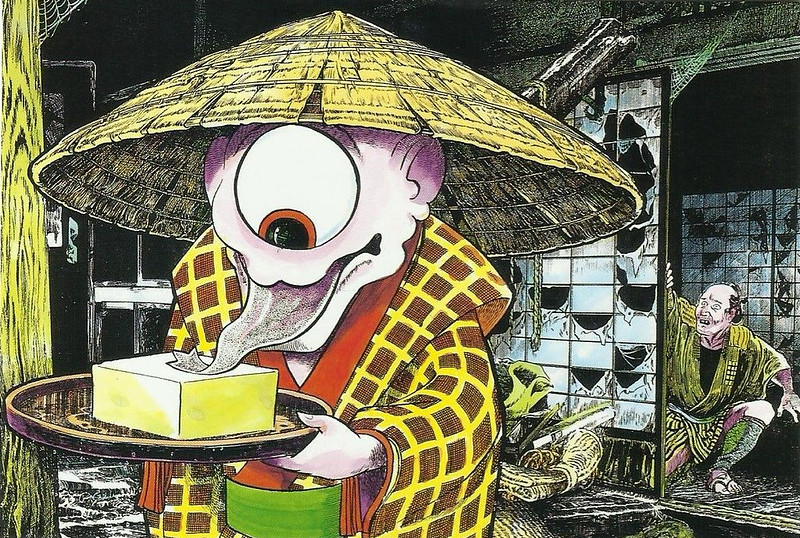

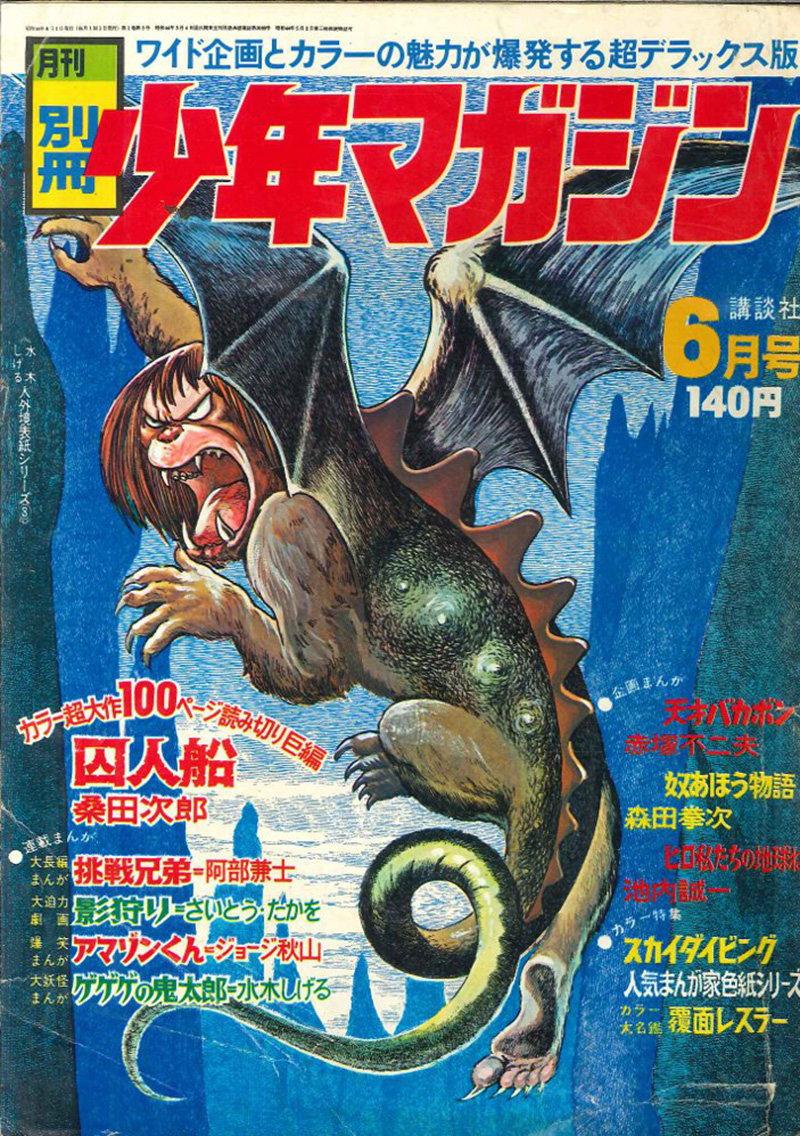

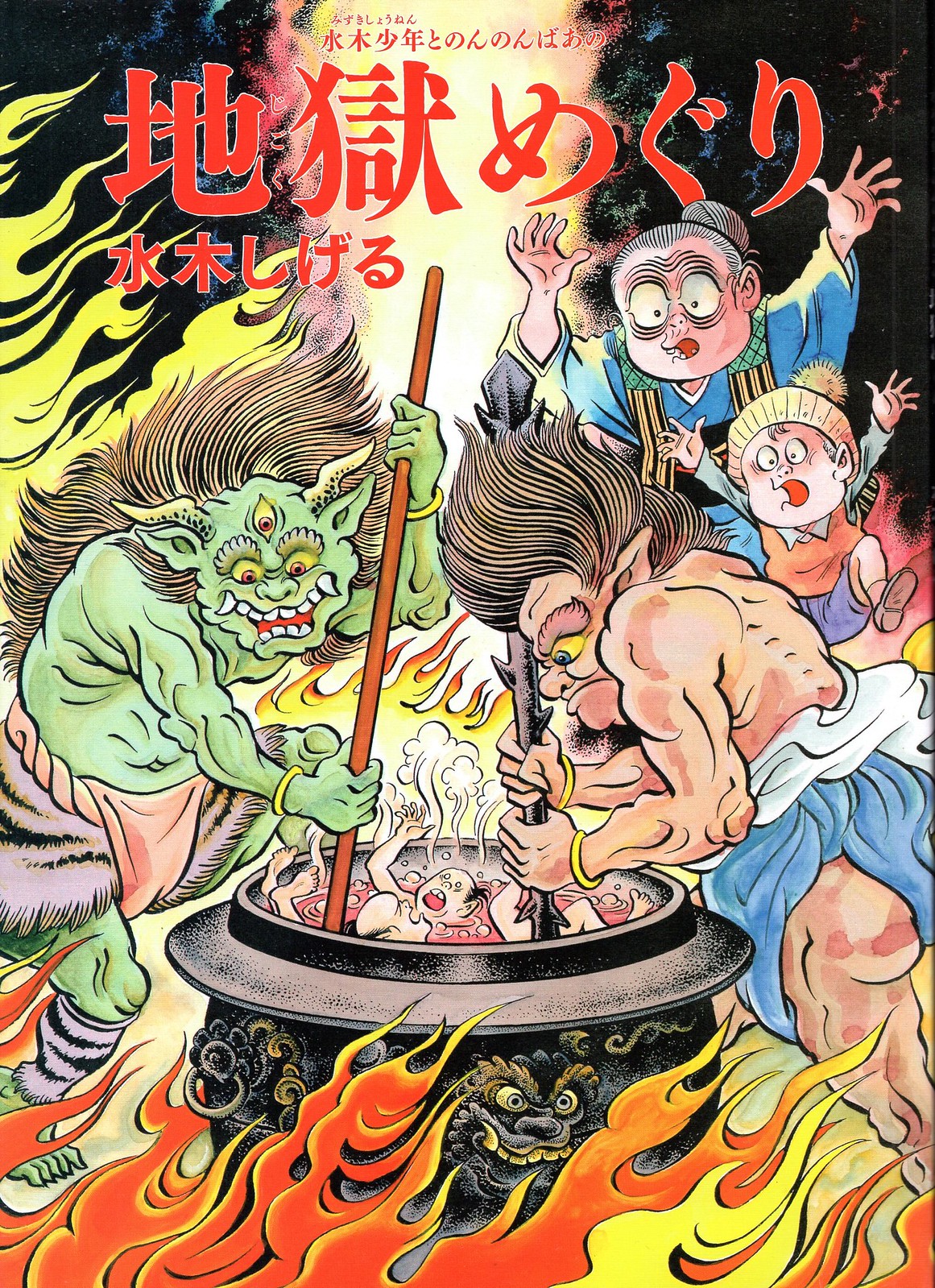

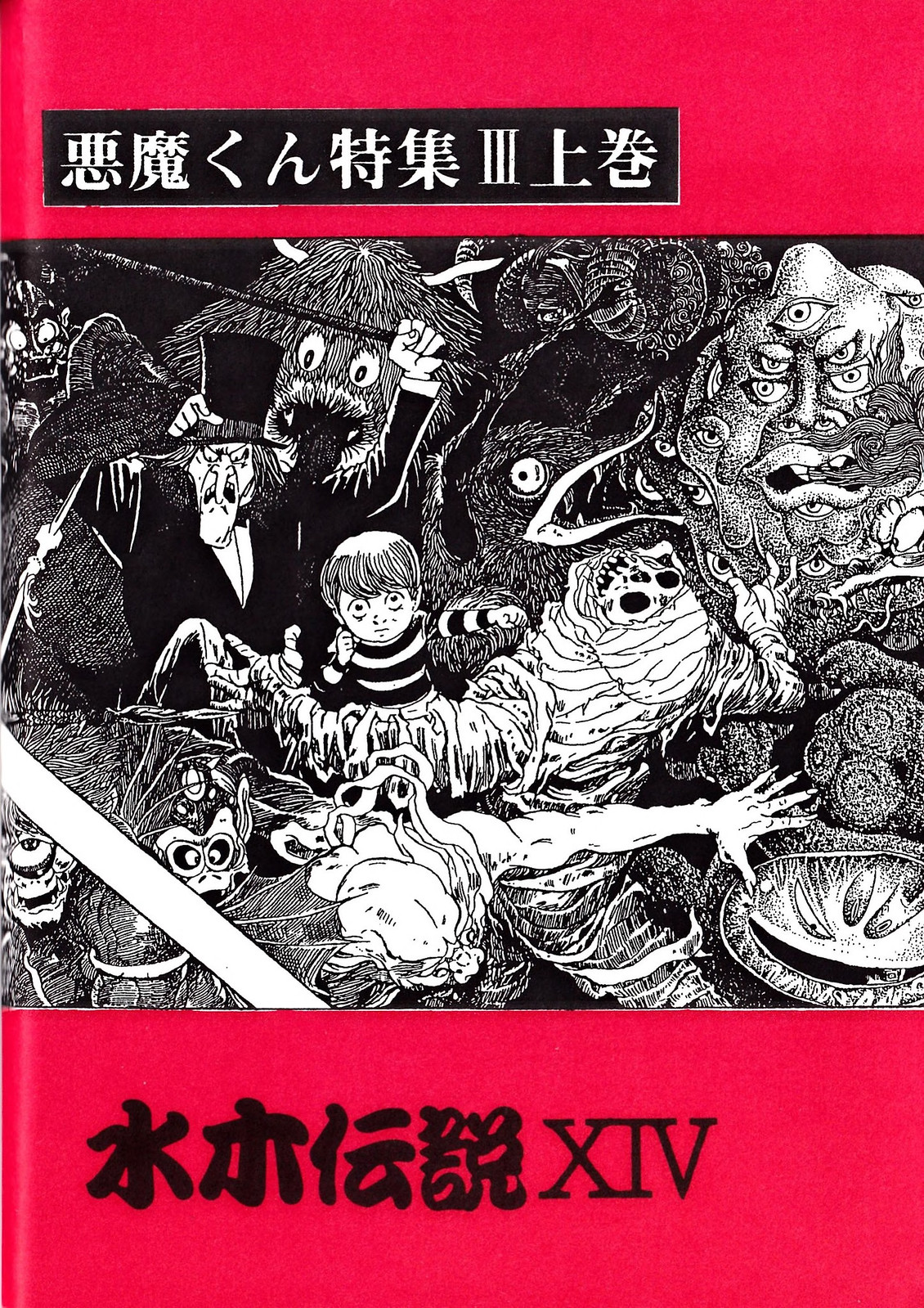

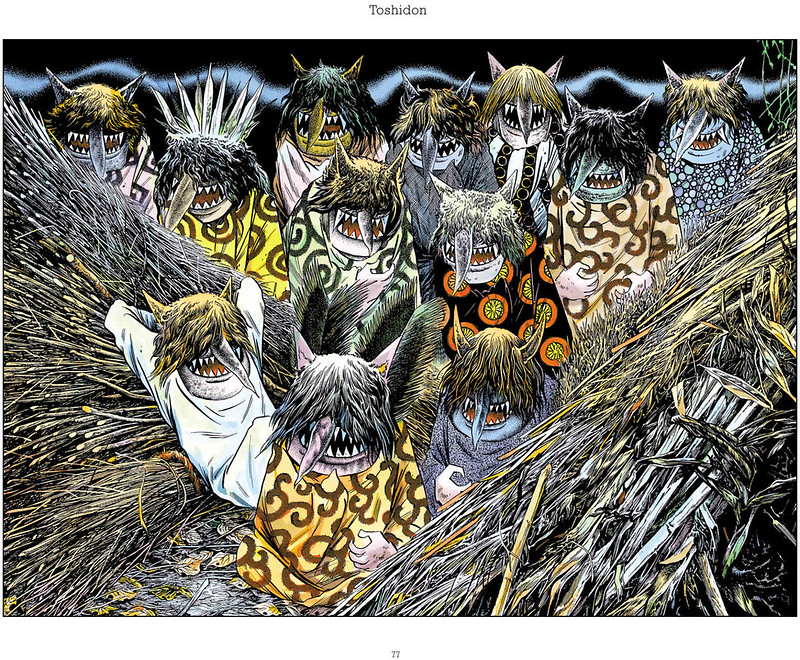

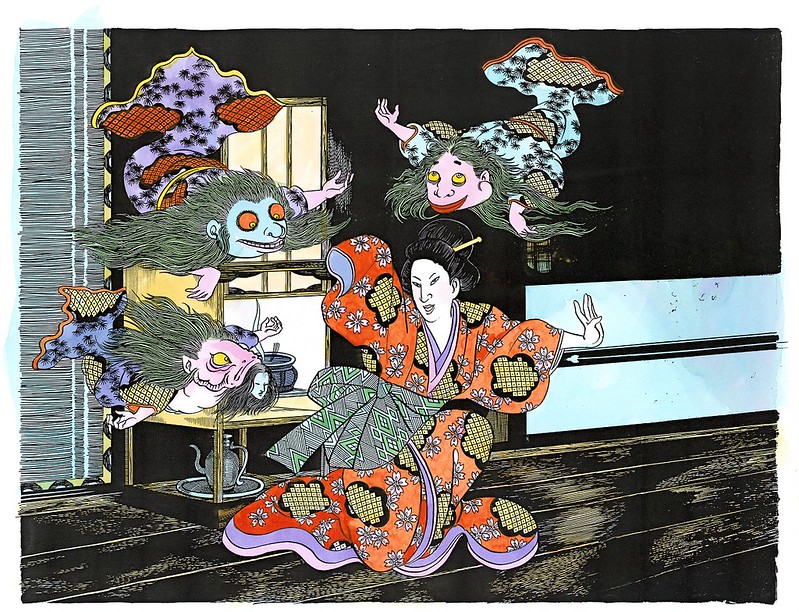

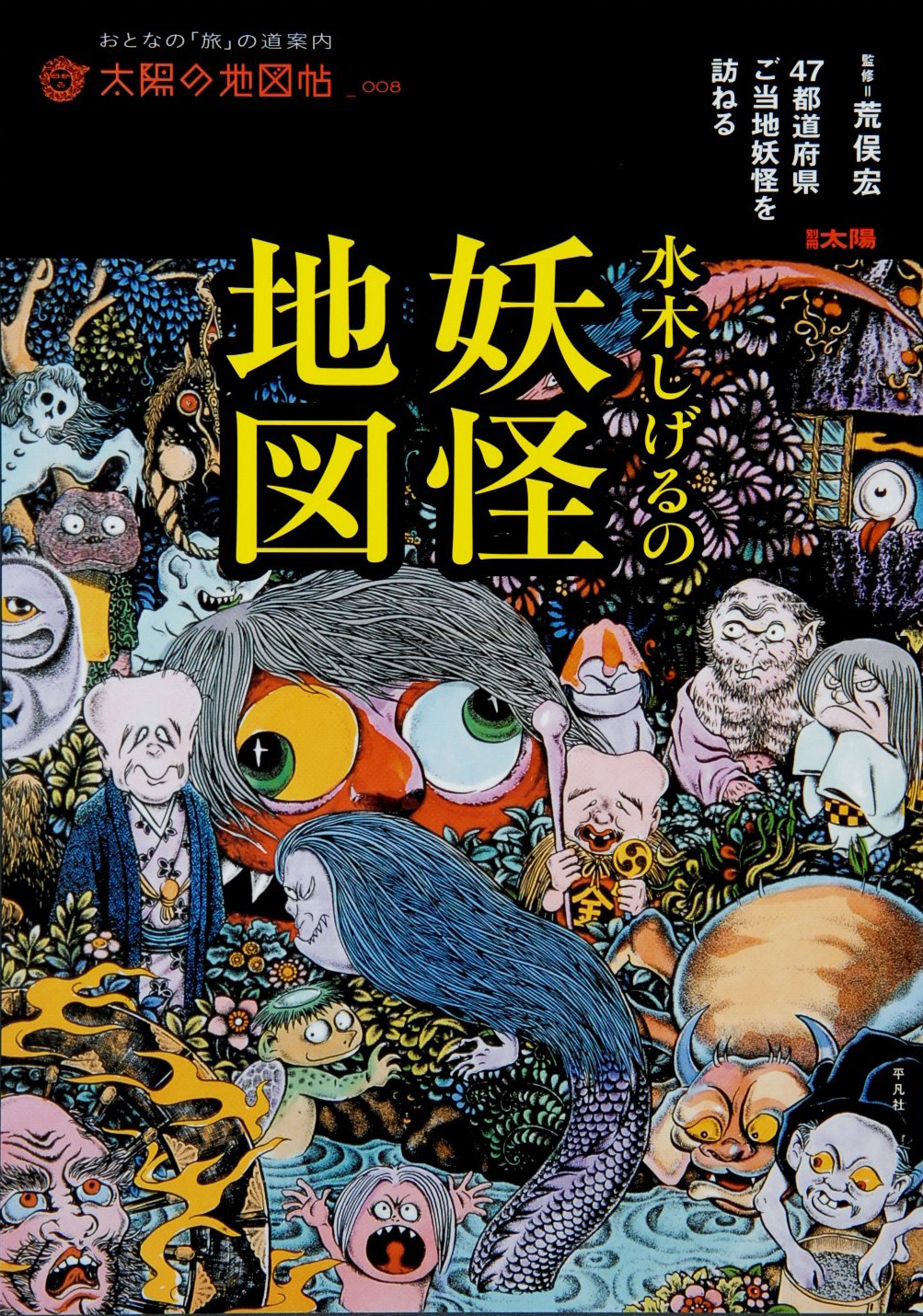

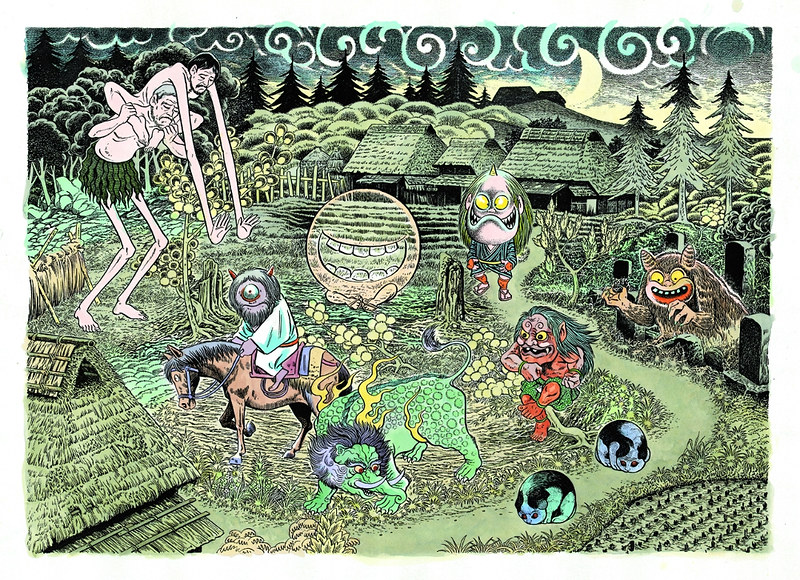

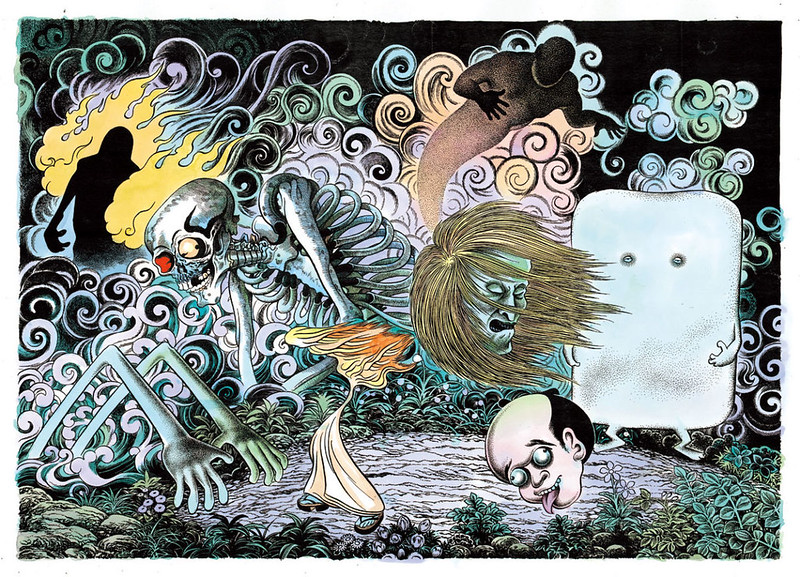

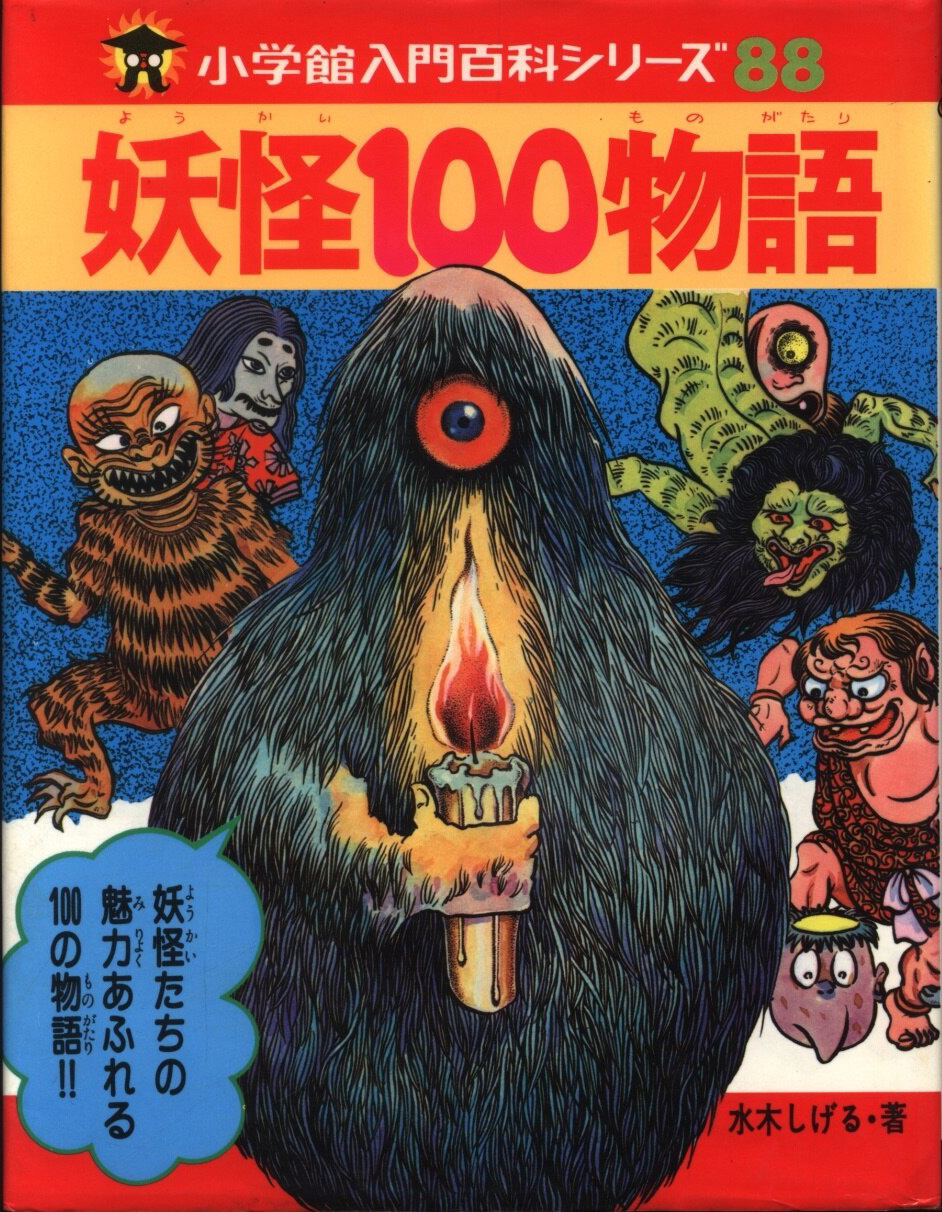

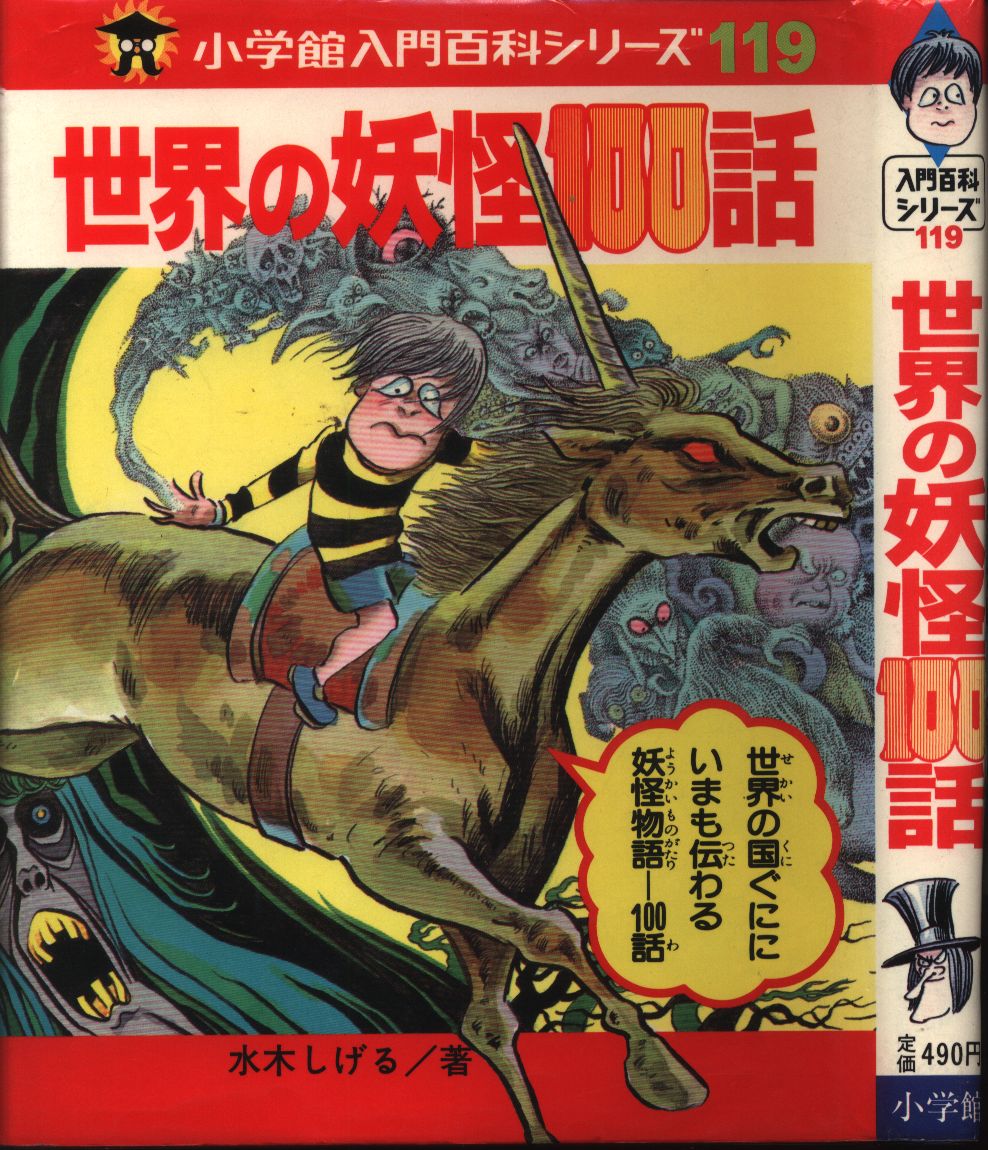

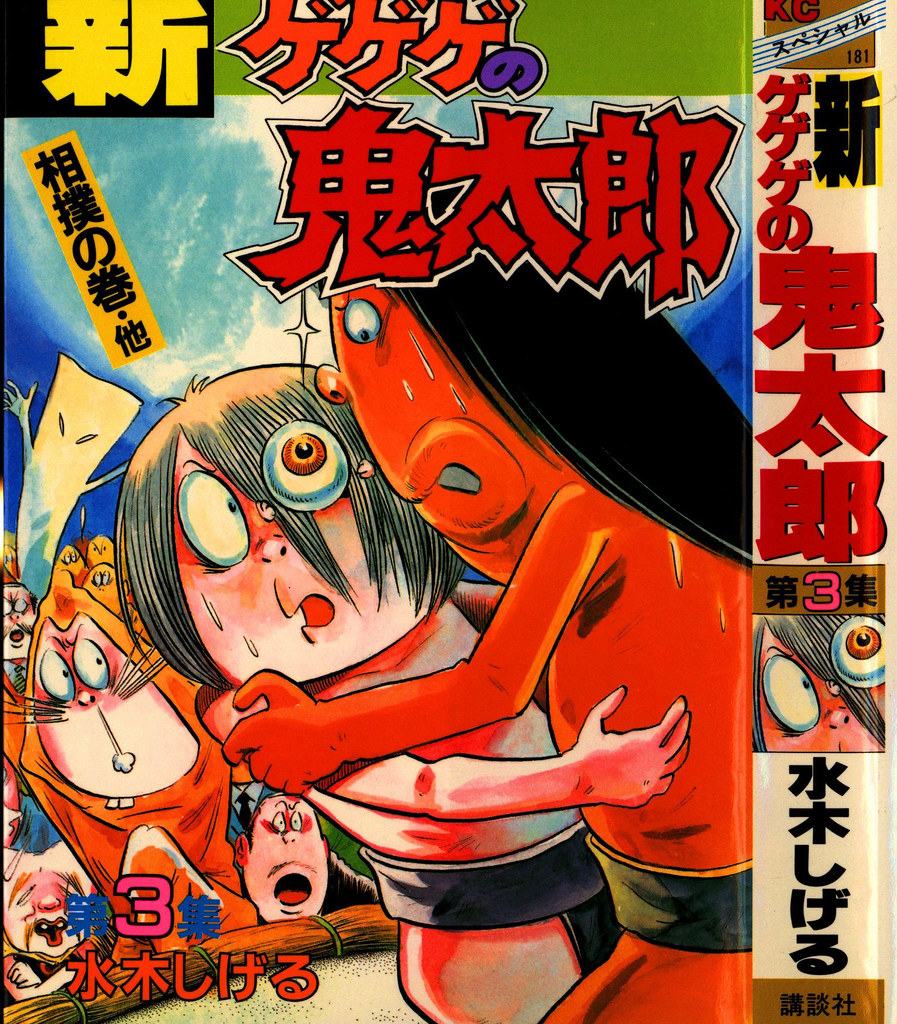

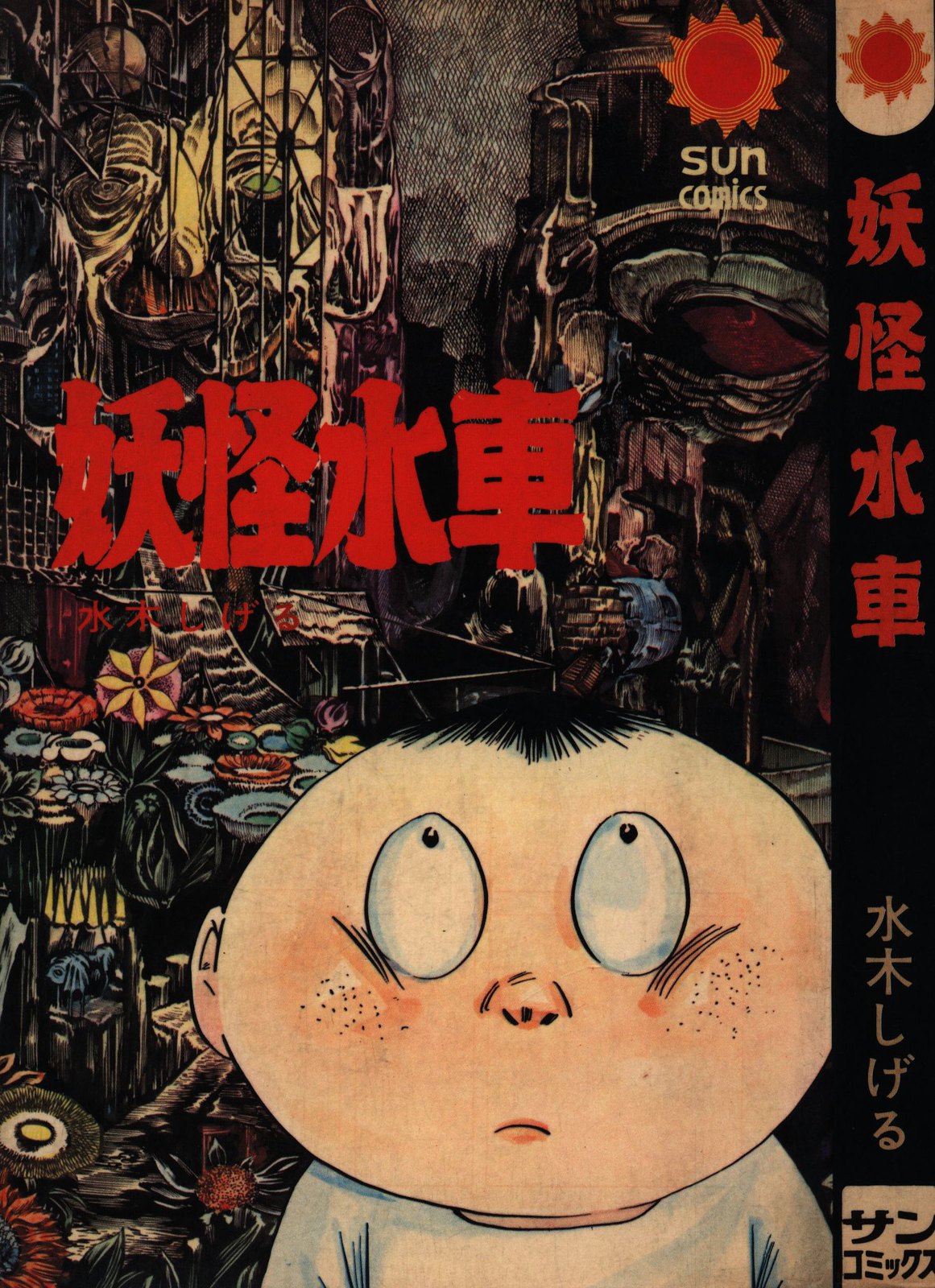

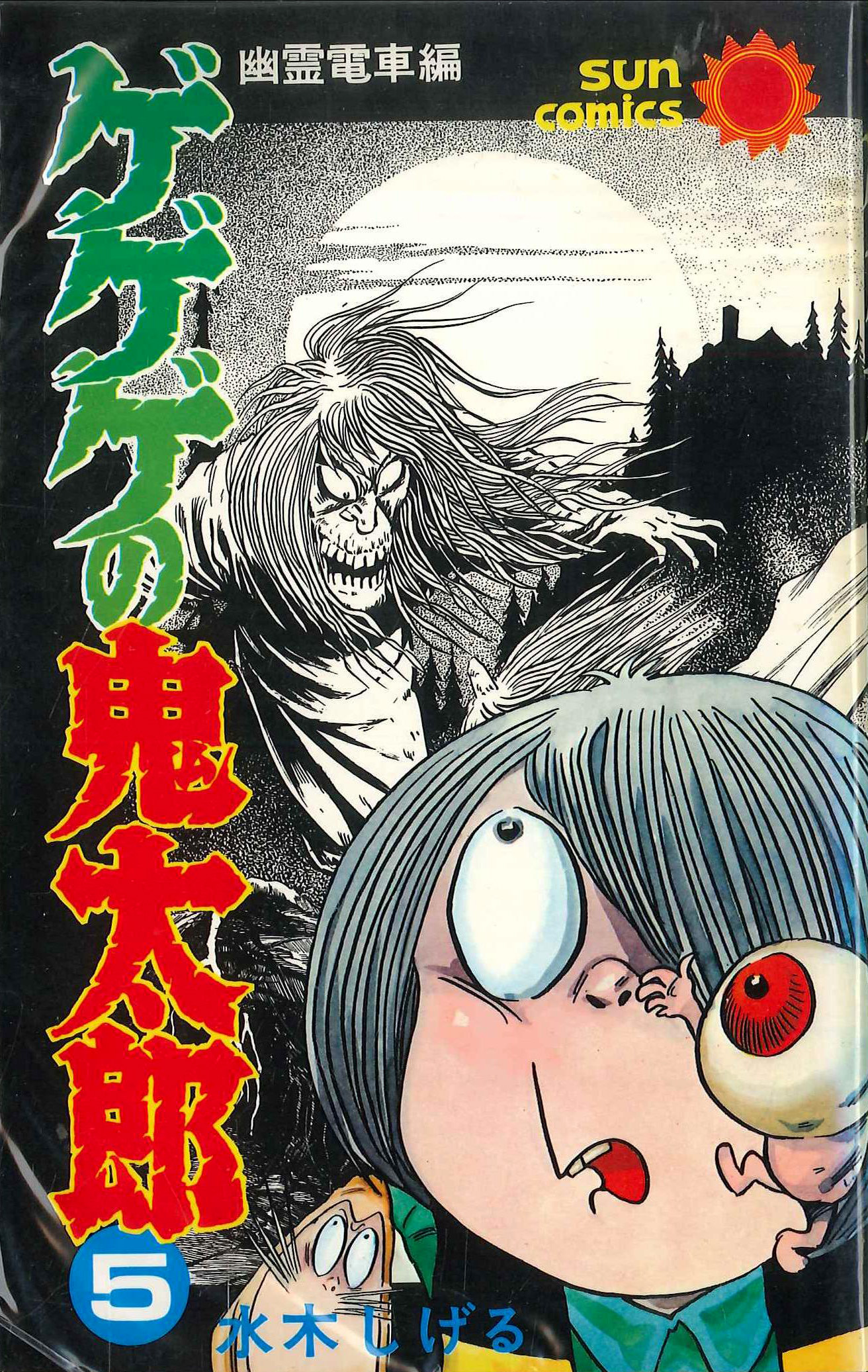

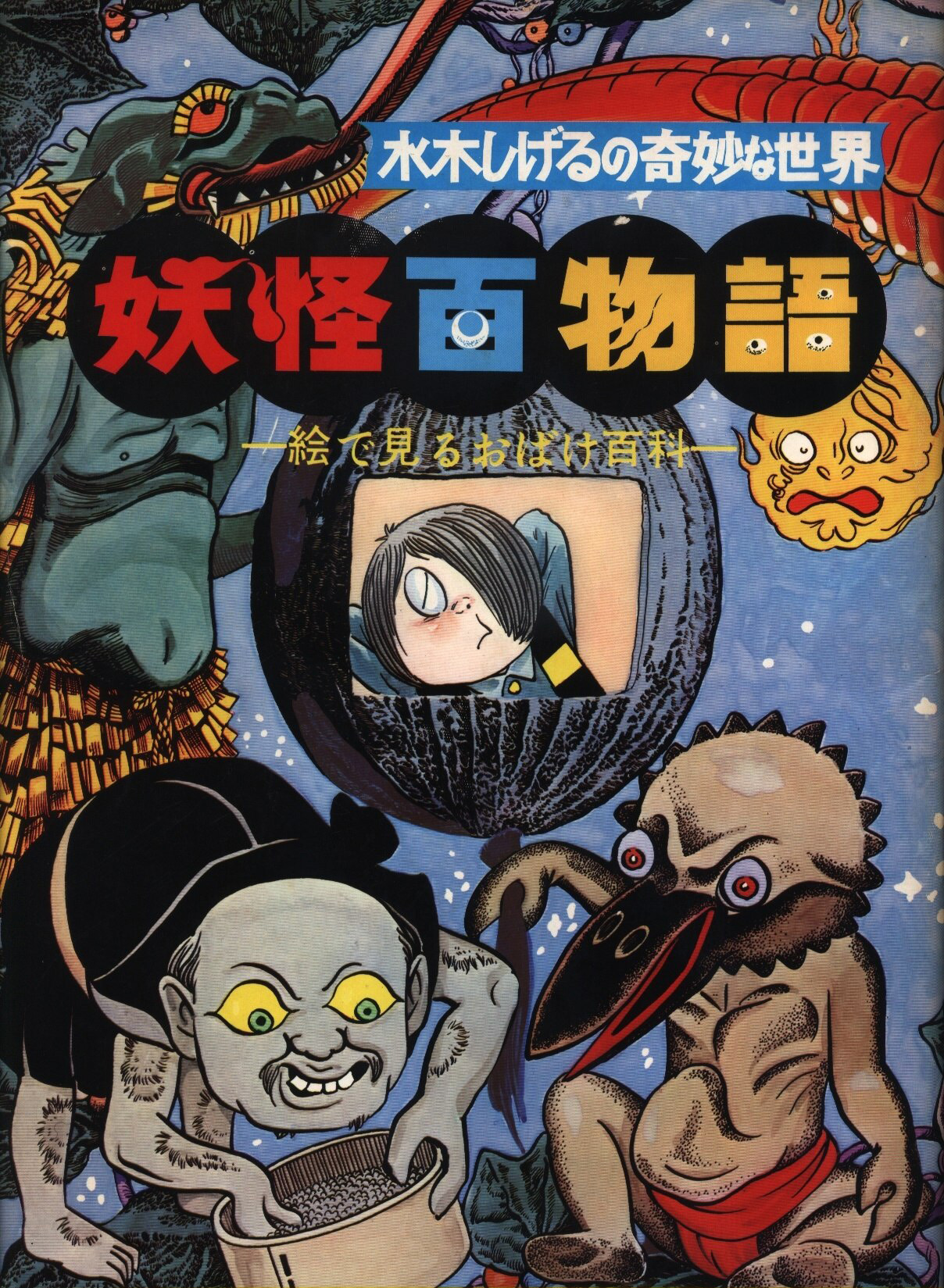

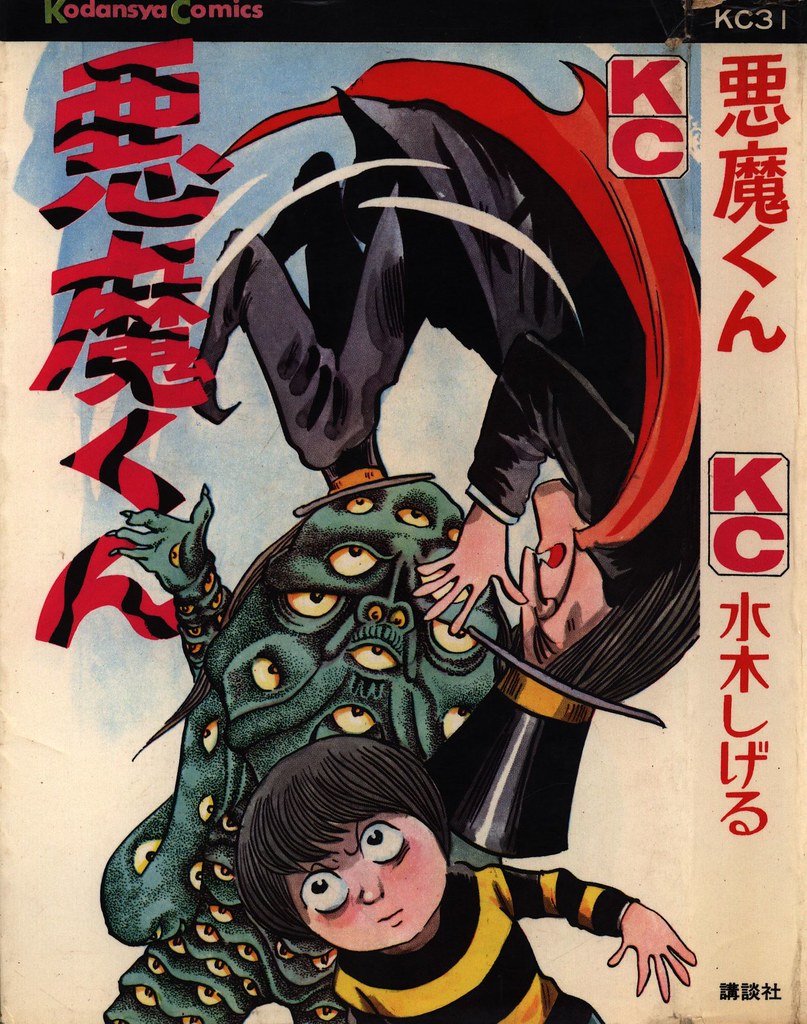

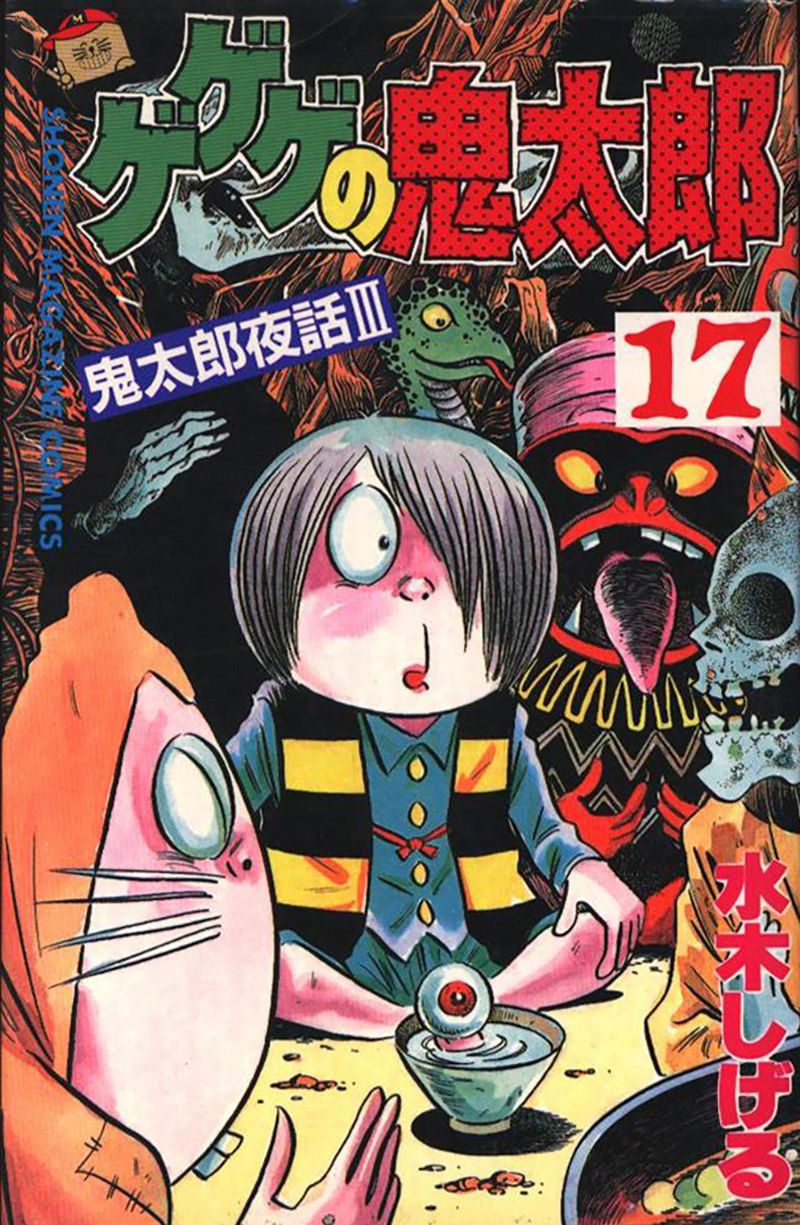

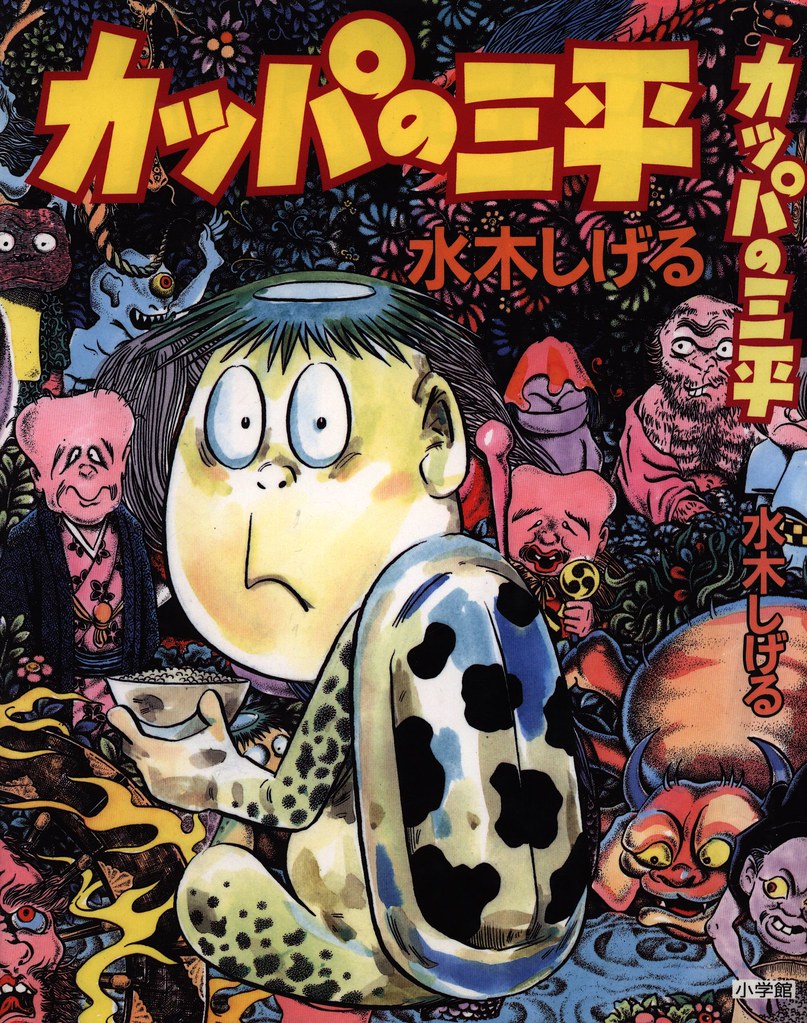

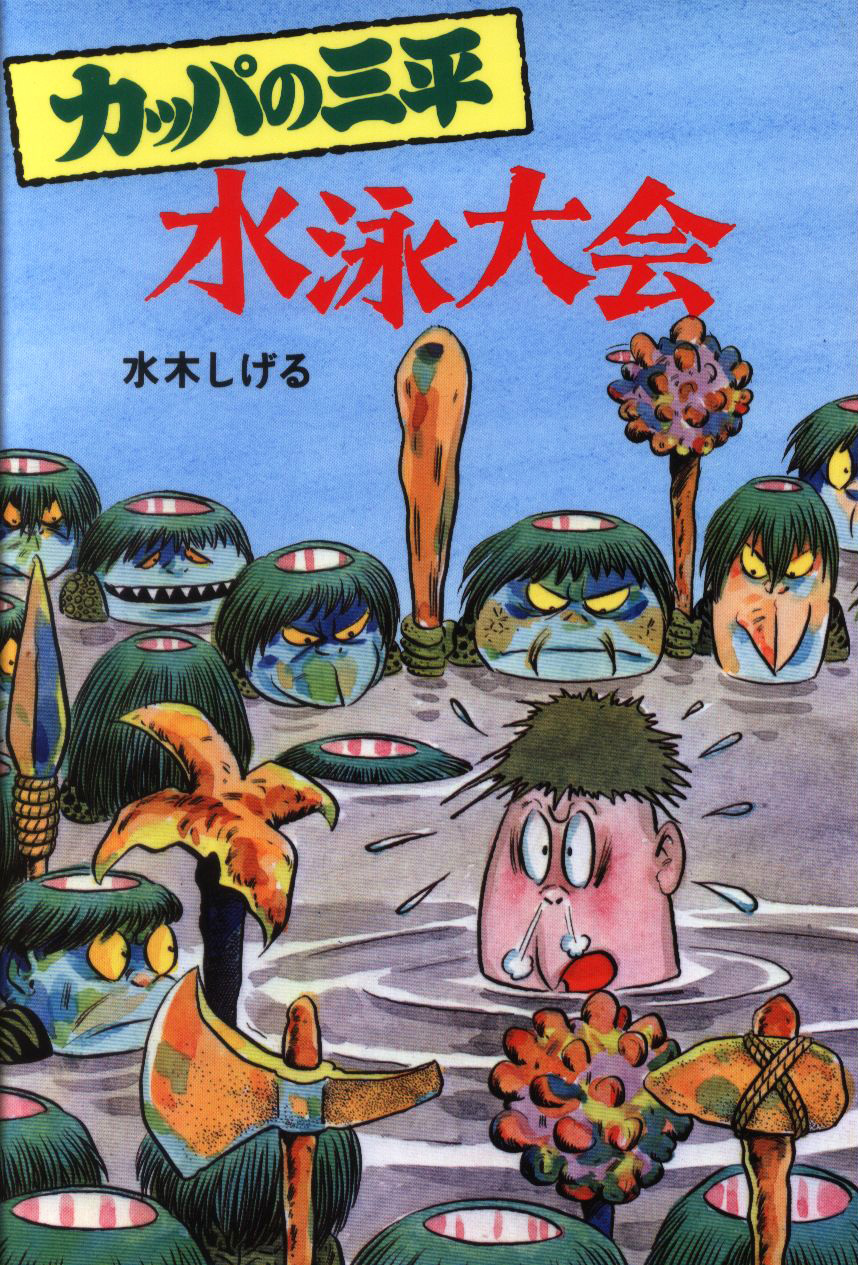

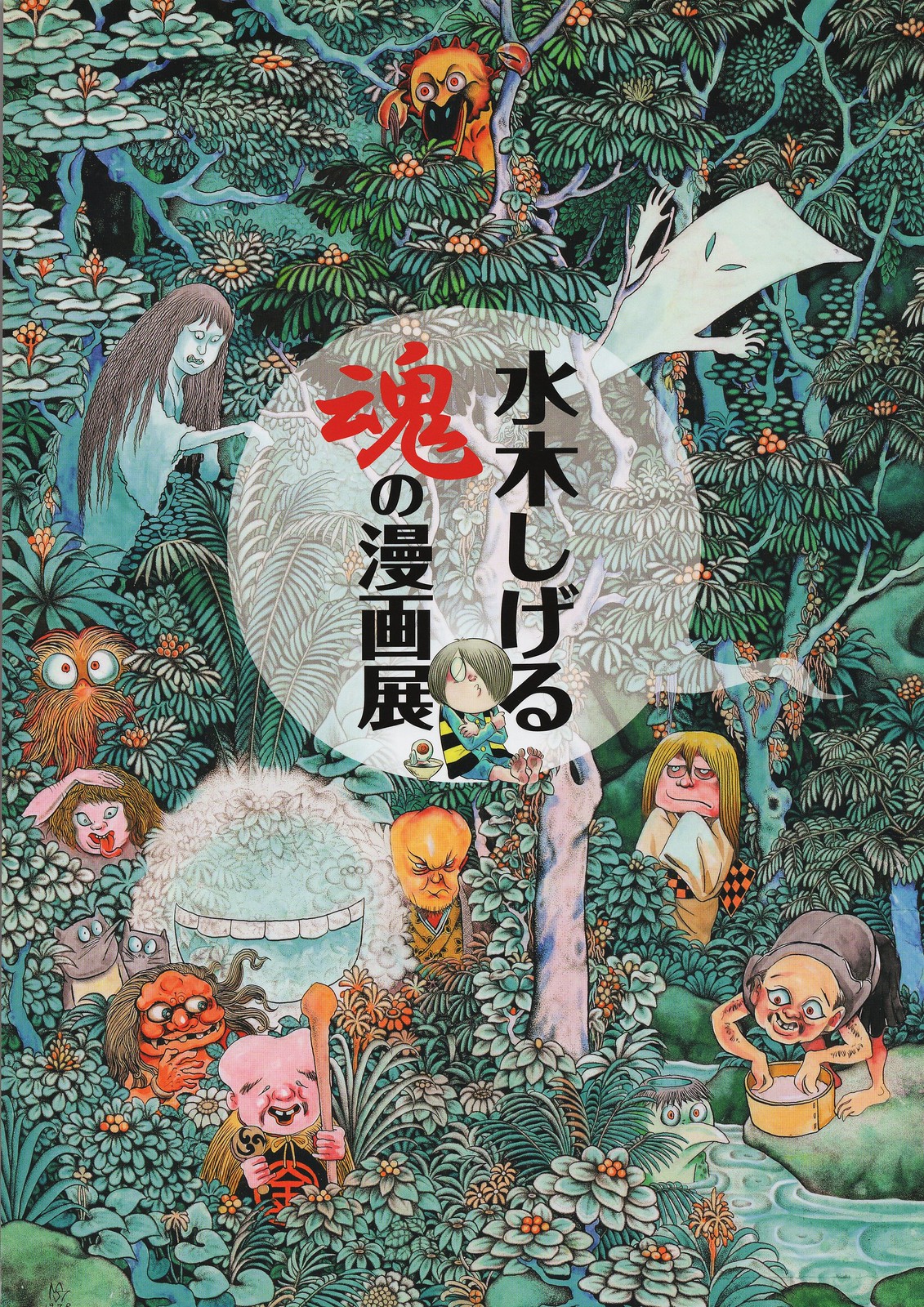

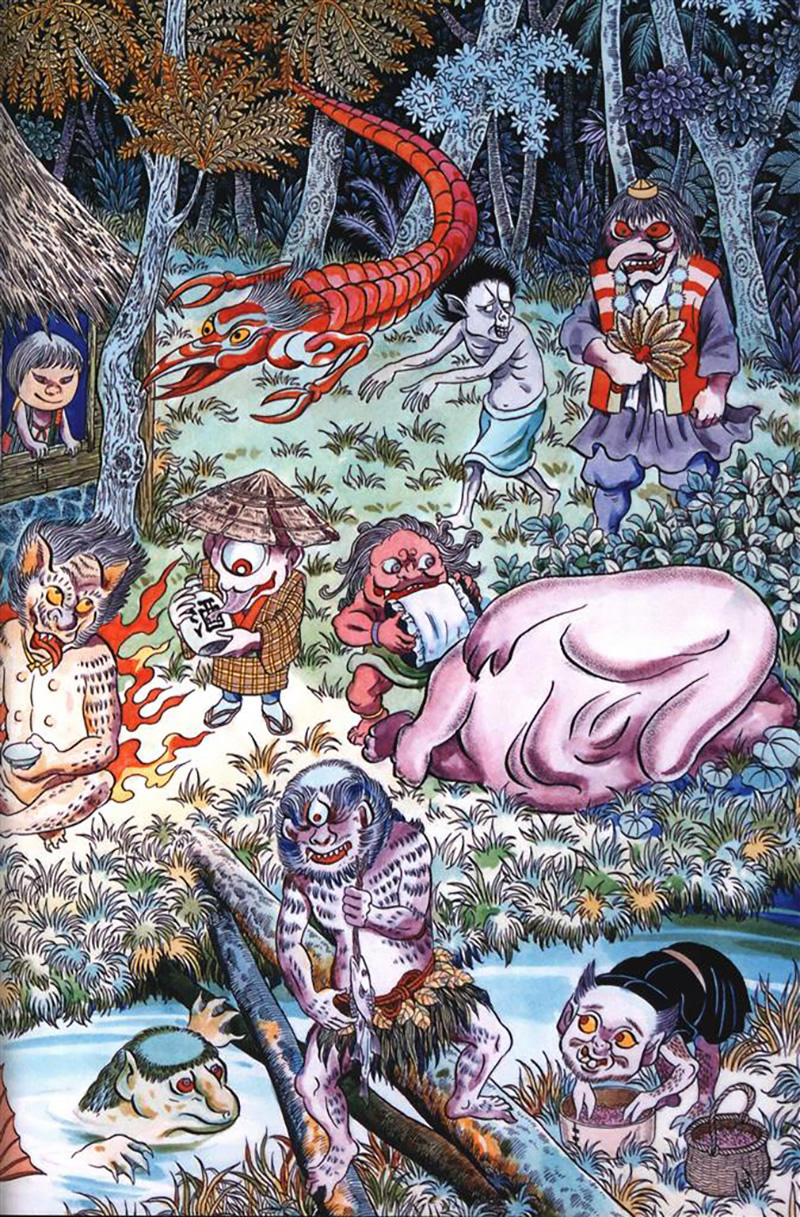

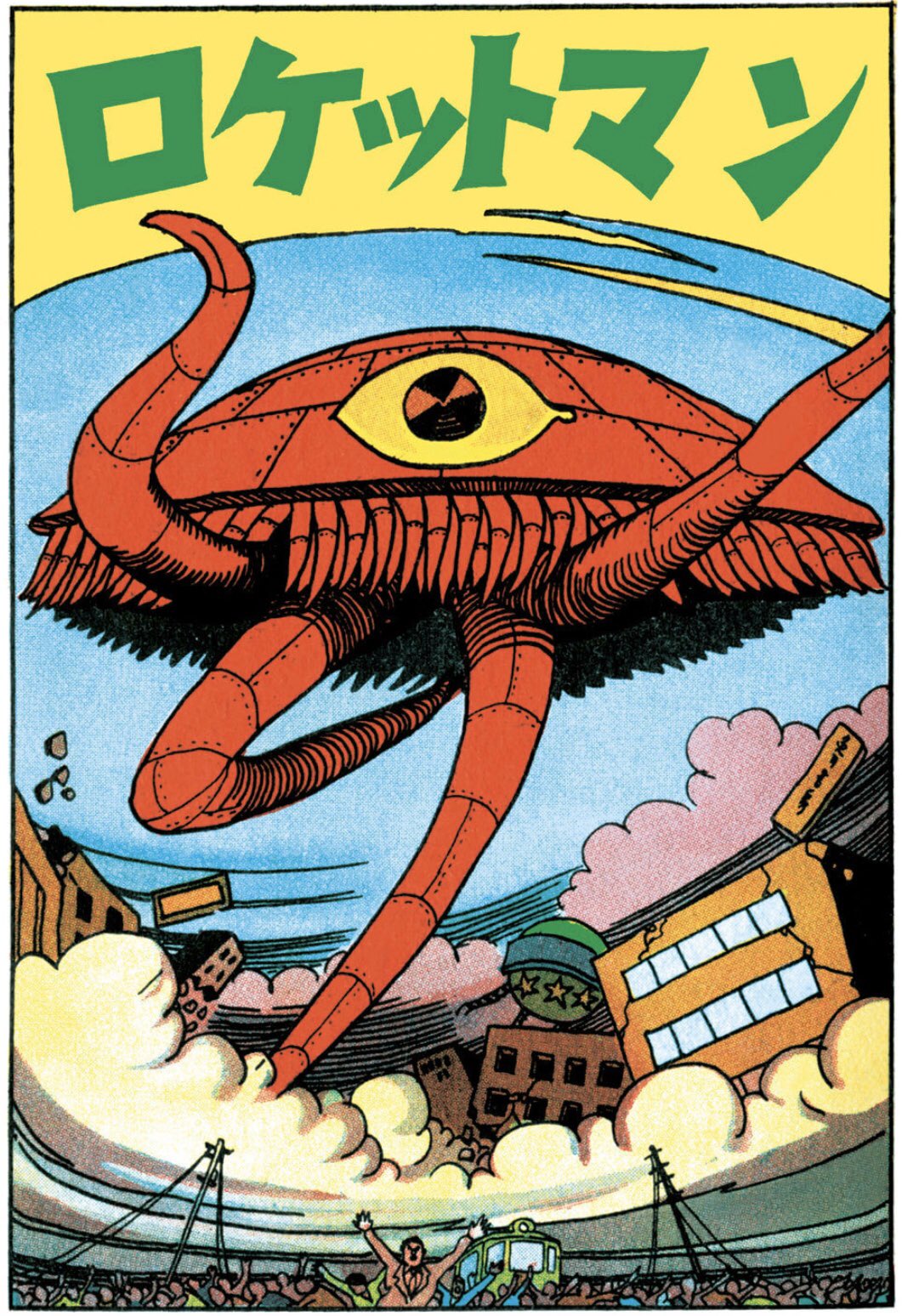

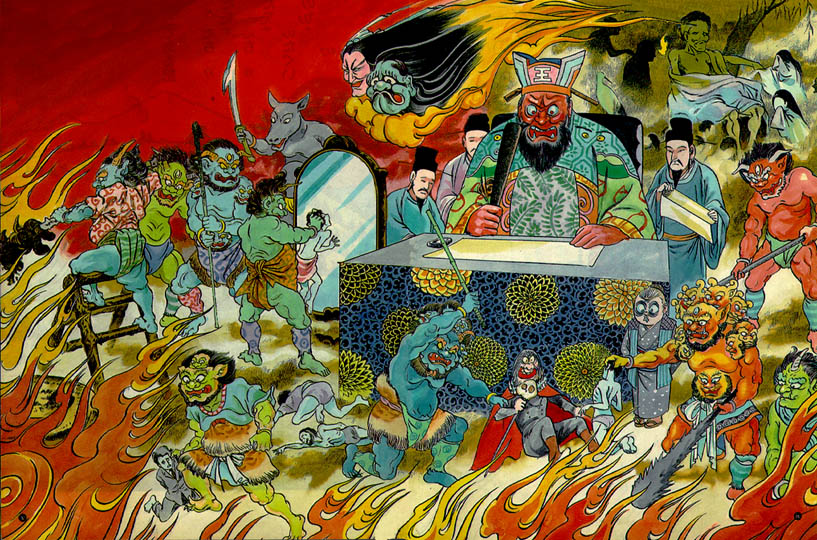

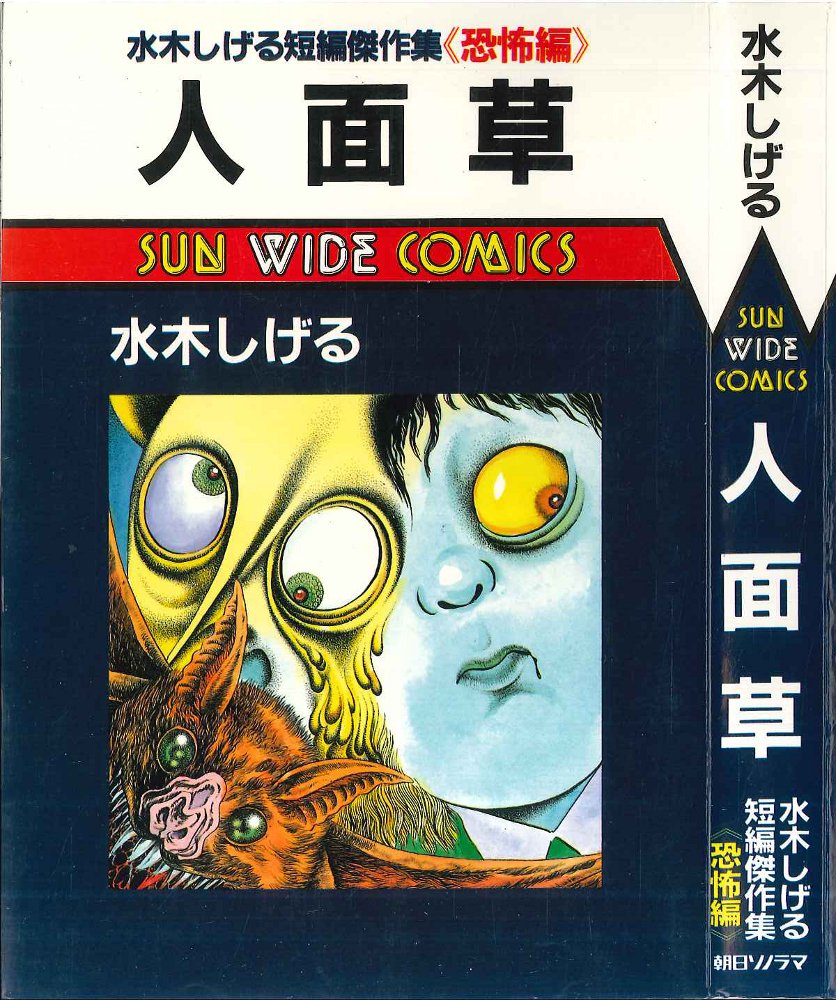

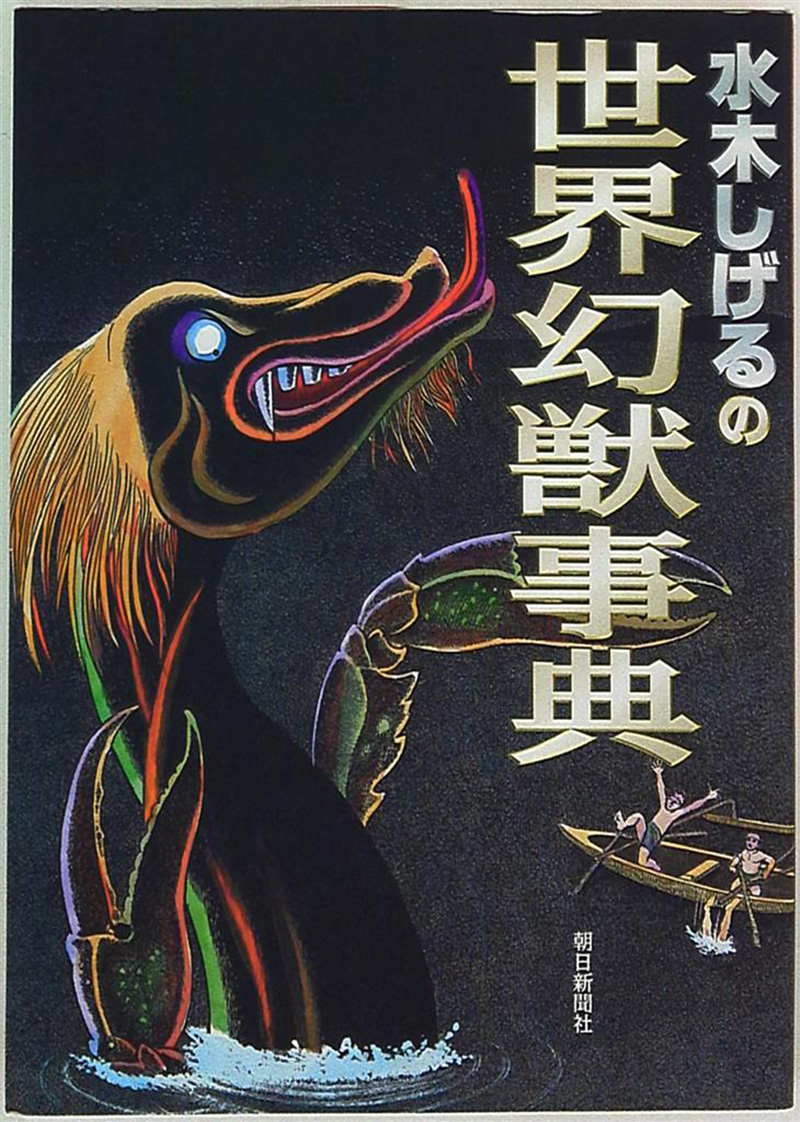

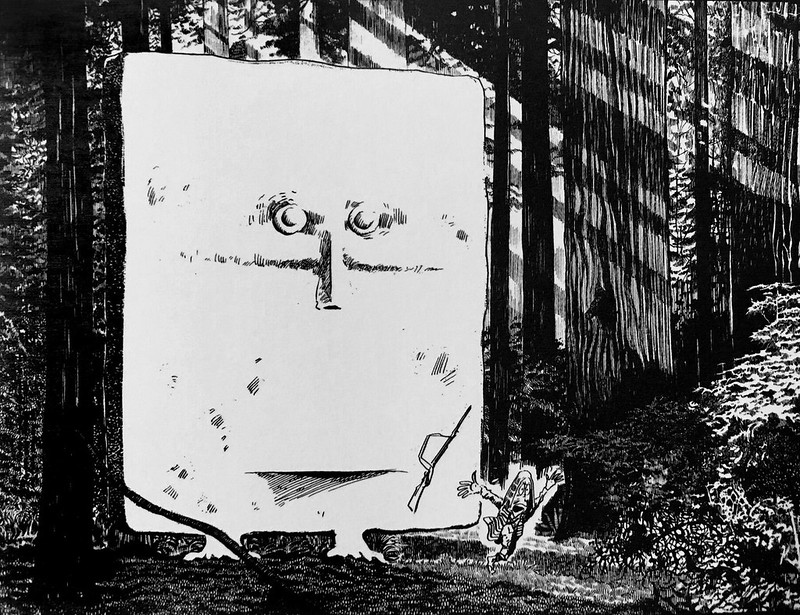

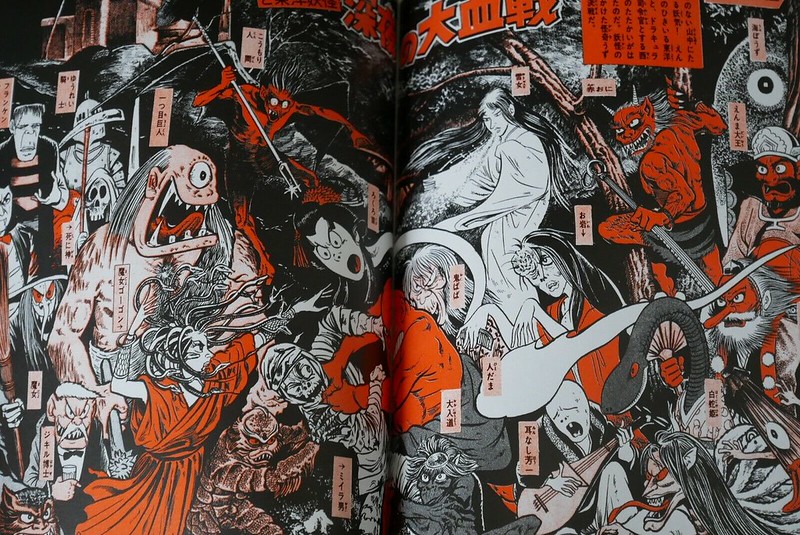

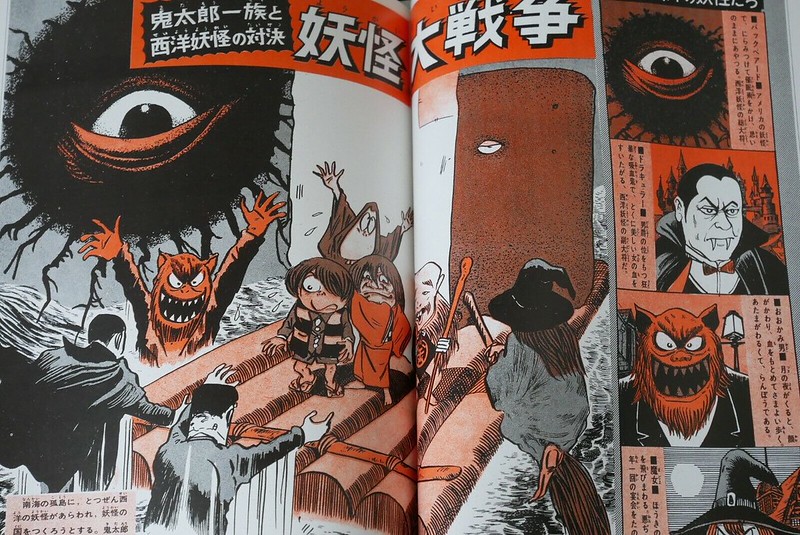

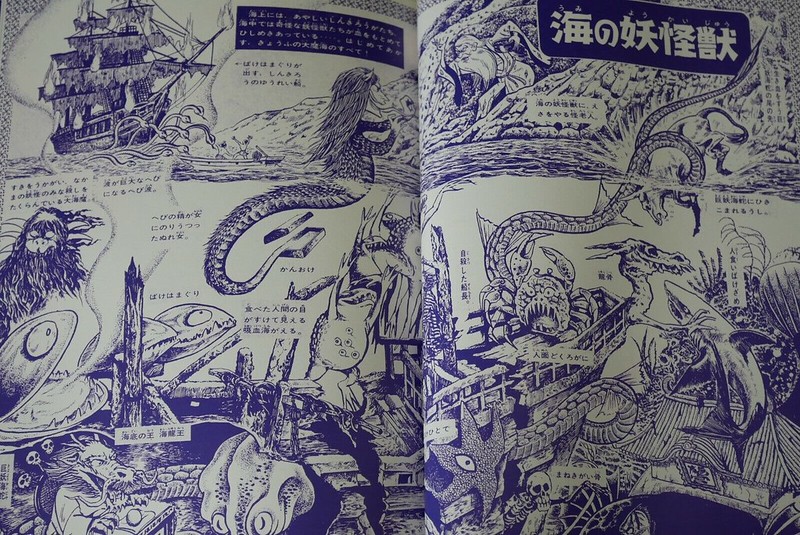

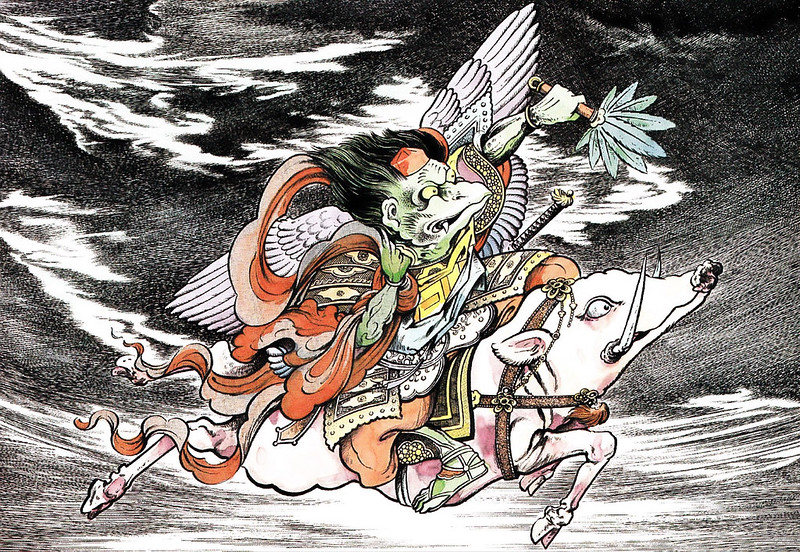

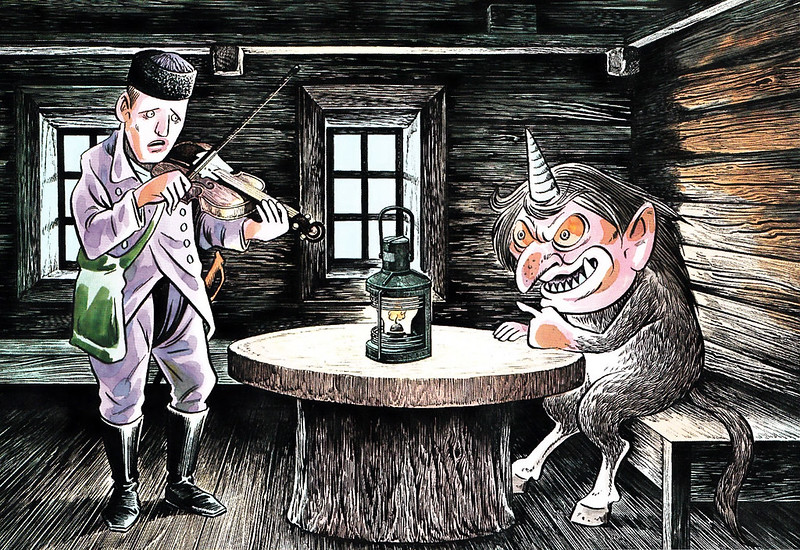

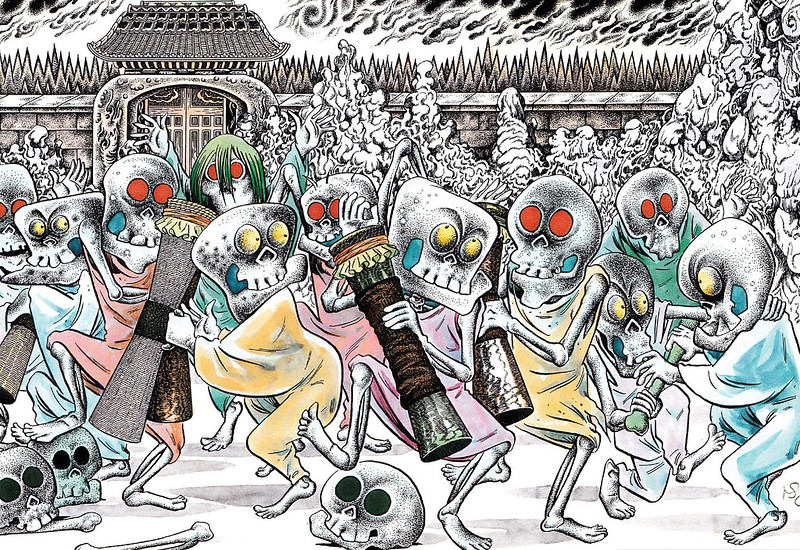

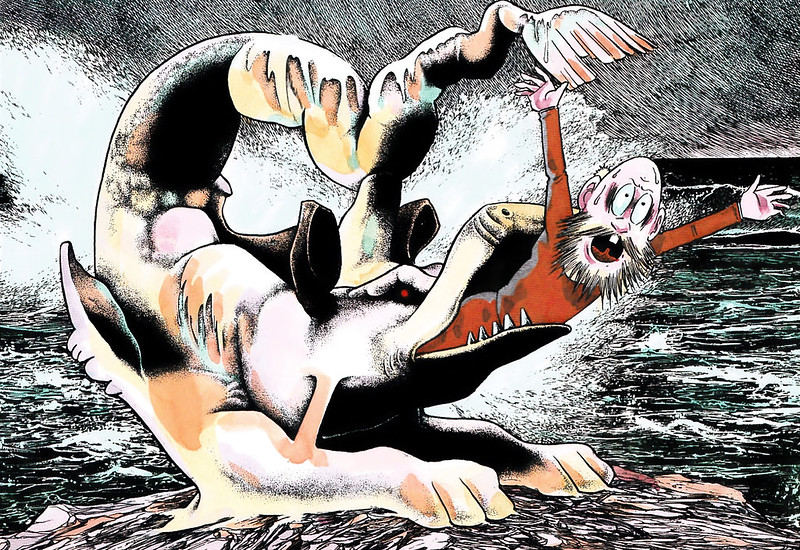

Shigeru Mizuki (1922 - 2015)

Previous Monster Brains posts sharing the work of Mizuki can be found below

Yokai / Mythological Creature Illustrations, 2002Illustrated Guide To Yokai Monsters, 2004 God of Pestilence Yokai, 1974 Yokai Illustrations

And finally, the first post on Monster Brains sharing the work of Mizuki in 2006.

Shigeru Mizuki - Yokai / Mythological Creature Illustrations, 2002

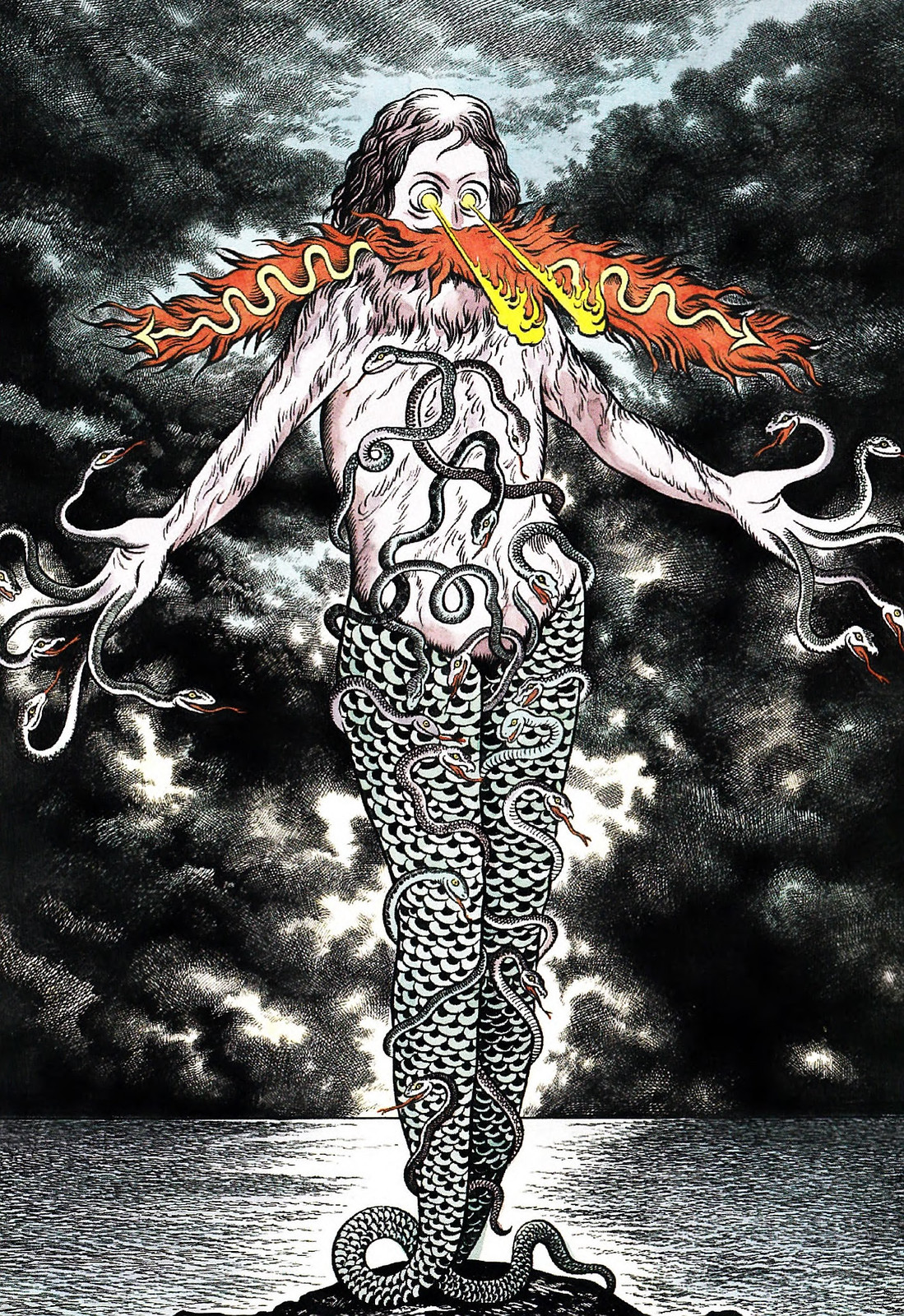

Typhon

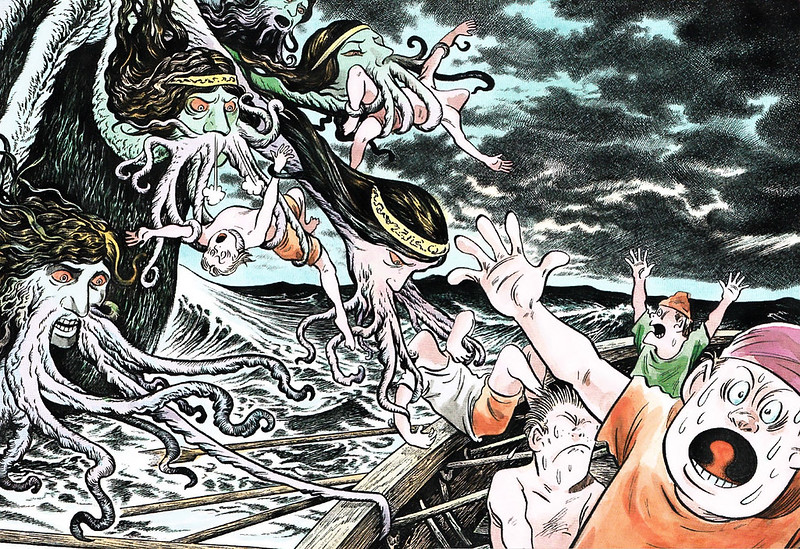

Typhon  Scylla

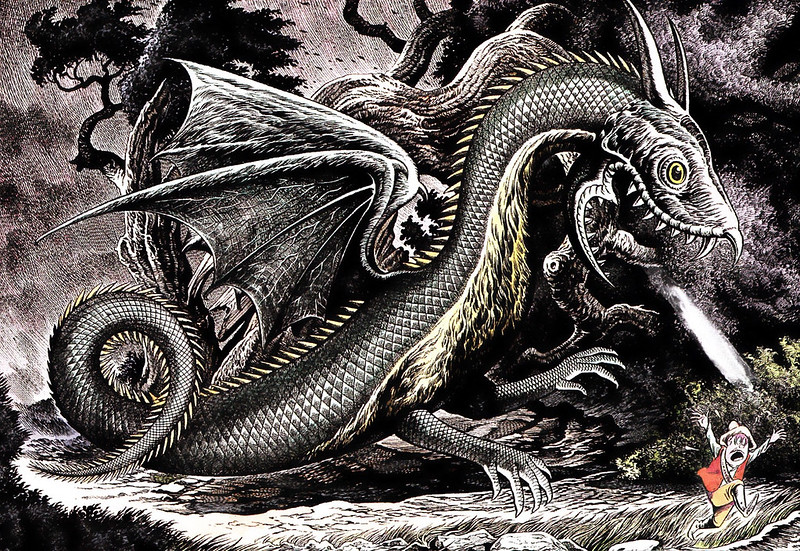

Scylla  Dragon

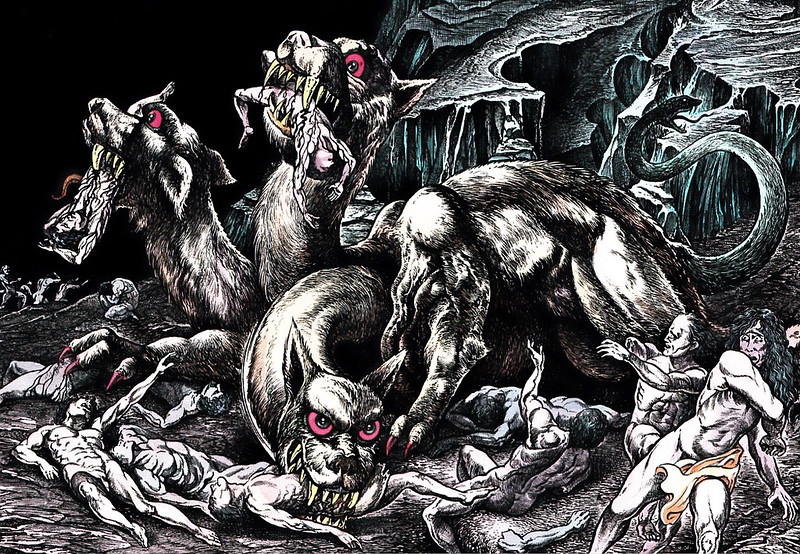

Dragon  Cerberus

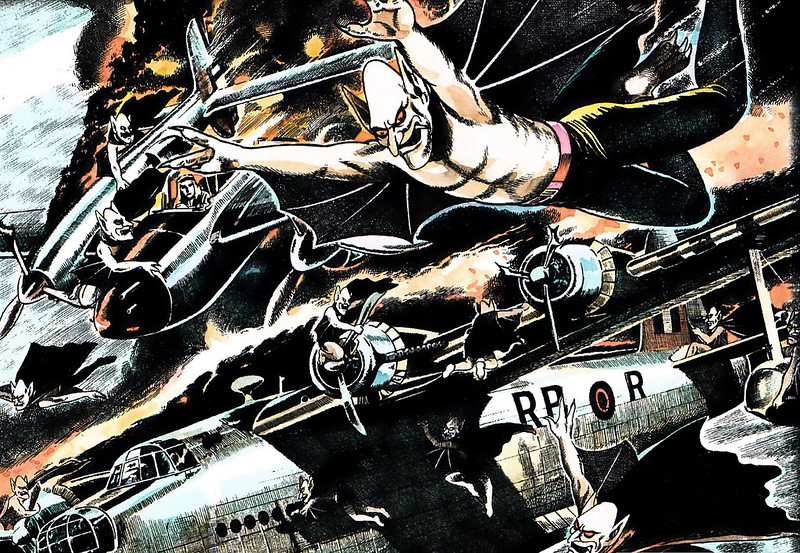

Cerberus  Gremlin

Gremlin  Glaukos

Glaukos  Rukh

Rukh  Backbeared

Backbeared  Zunuqua

Zunuqua  Waiwai

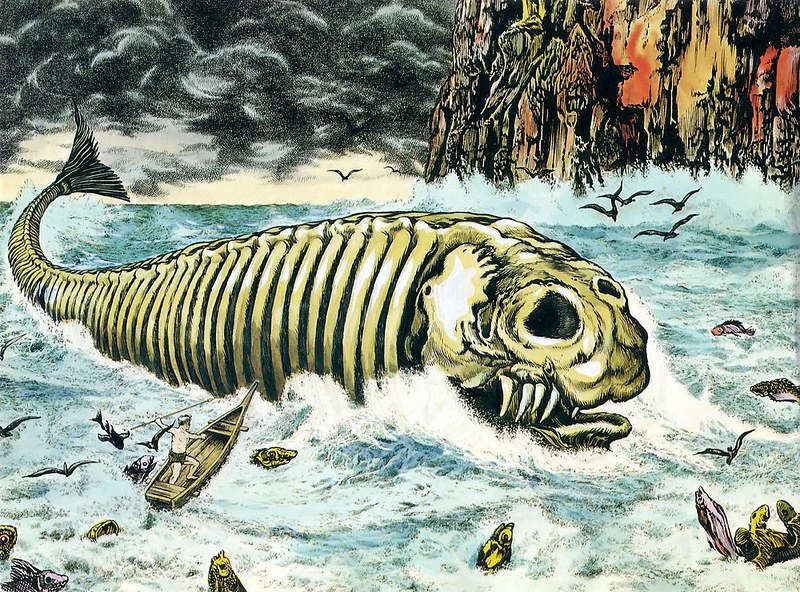

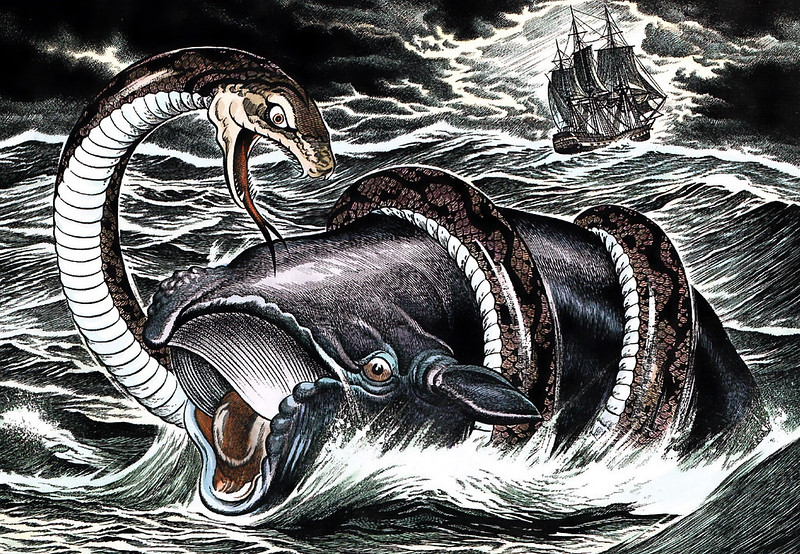

Waiwai  Sea Serpent

Sea Serpent  Centaurs

Centaurs Chon Chon

Chon Chon  Leviathan

Leviathan  Tengu of China

Tengu of China  Cholt

Cholt  Melusine

Melusine  Buer

Buer  Hippogriff

Hippogriff  Harpy

Harpy  Balor

Balor  Griffen

Griffen  Garuda

Garuda  The Death

The Death  Basilisk

Basilisk  Polyphemus

Polyphemus  Salamander

Salamander  Phorkys

Phorkys  Dragon

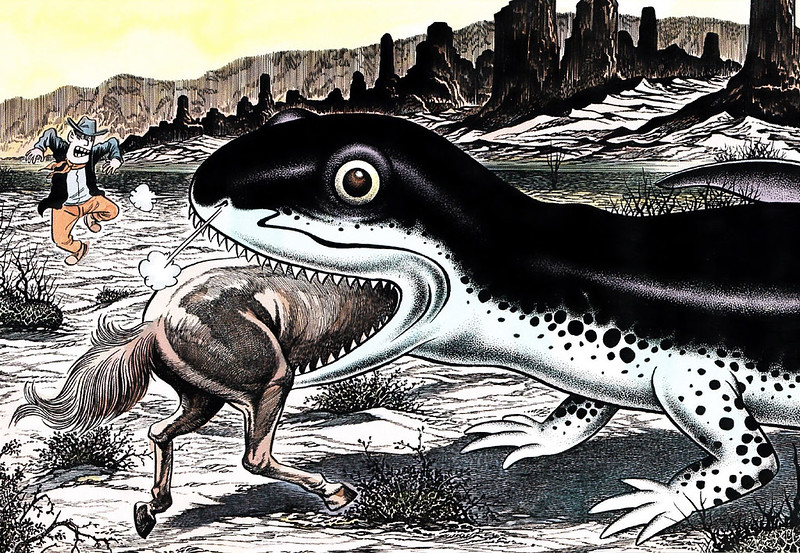

Dragon  Giant Newt

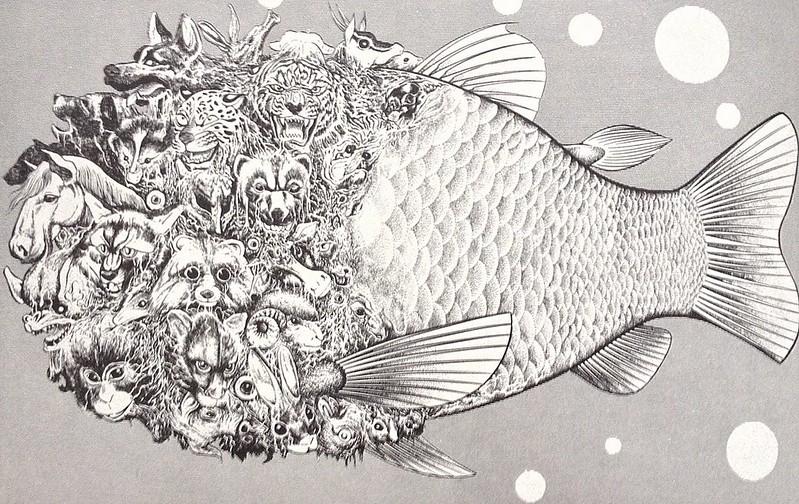

Giant Newt "This is an artbook/encyclopedia that came included with a set of Tarot Cards centered around Shigeru Mizuki's artwork. There are 80 Yokai/Mythical Creatures in total, and each one comes with their own entry that gives a little more information about the creature. Shigeru Mizuki himself considered mythical monsters/beasts outside of Japan types of Yokai, so these entries contain creatures from all around the world."

The complete book, including many more of Mizuki's illustrations of Yokai and other various mythological creatures can be viewed at Archive.org

Previous Monster Brains posts sharing the work of Mizuki can be found below.. Shigeru Mizuki - Illustrated Guide To Yokai Monsters, 2004 Shigeru Mizuki - God of Pestilence Shigeru Mizuki's Yokai, 1974 Shigeru Mizuki - Yokai Illustrations And finally, the first post on Monster Brains sharing the work of Mizuki in 2006..

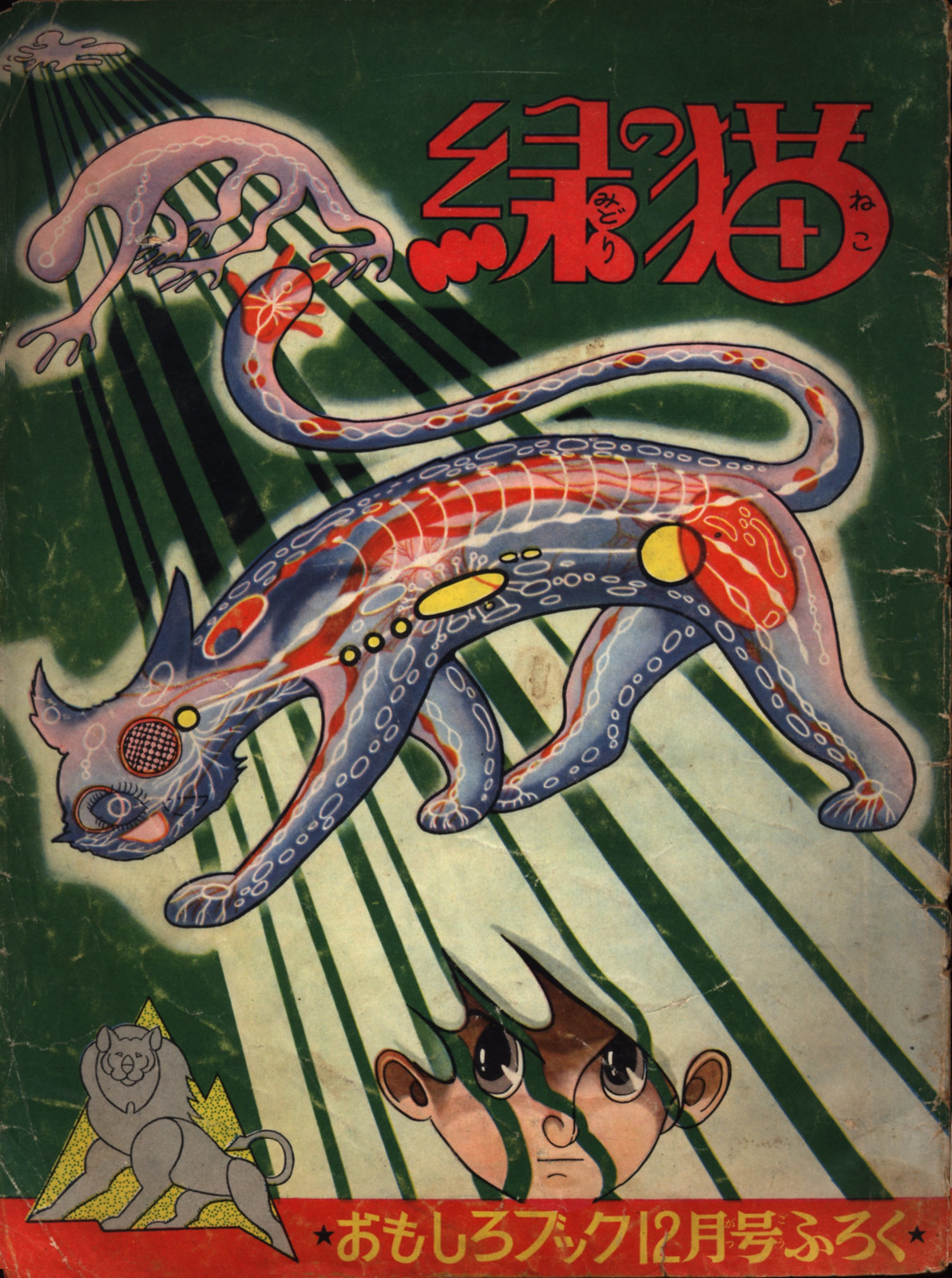

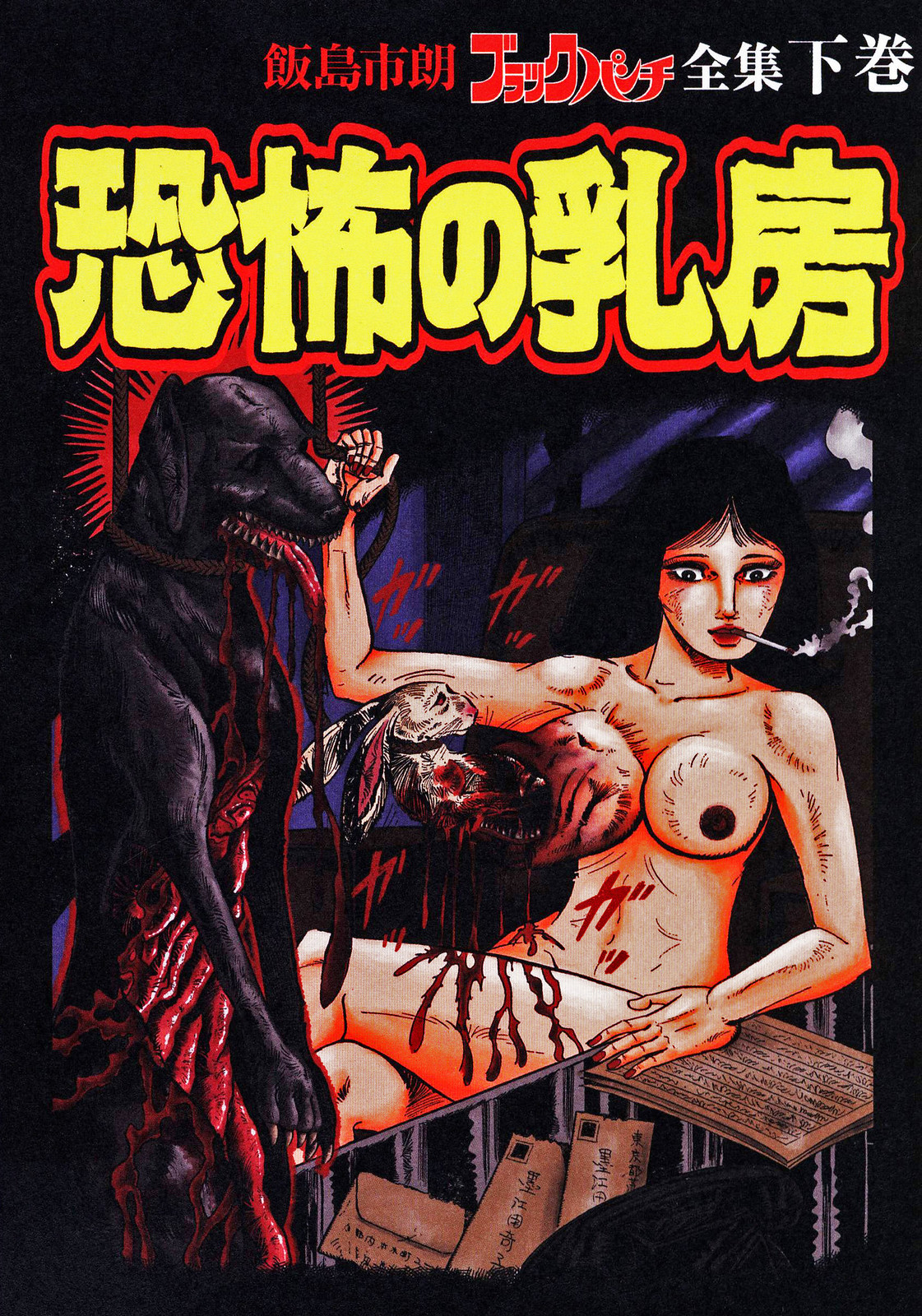

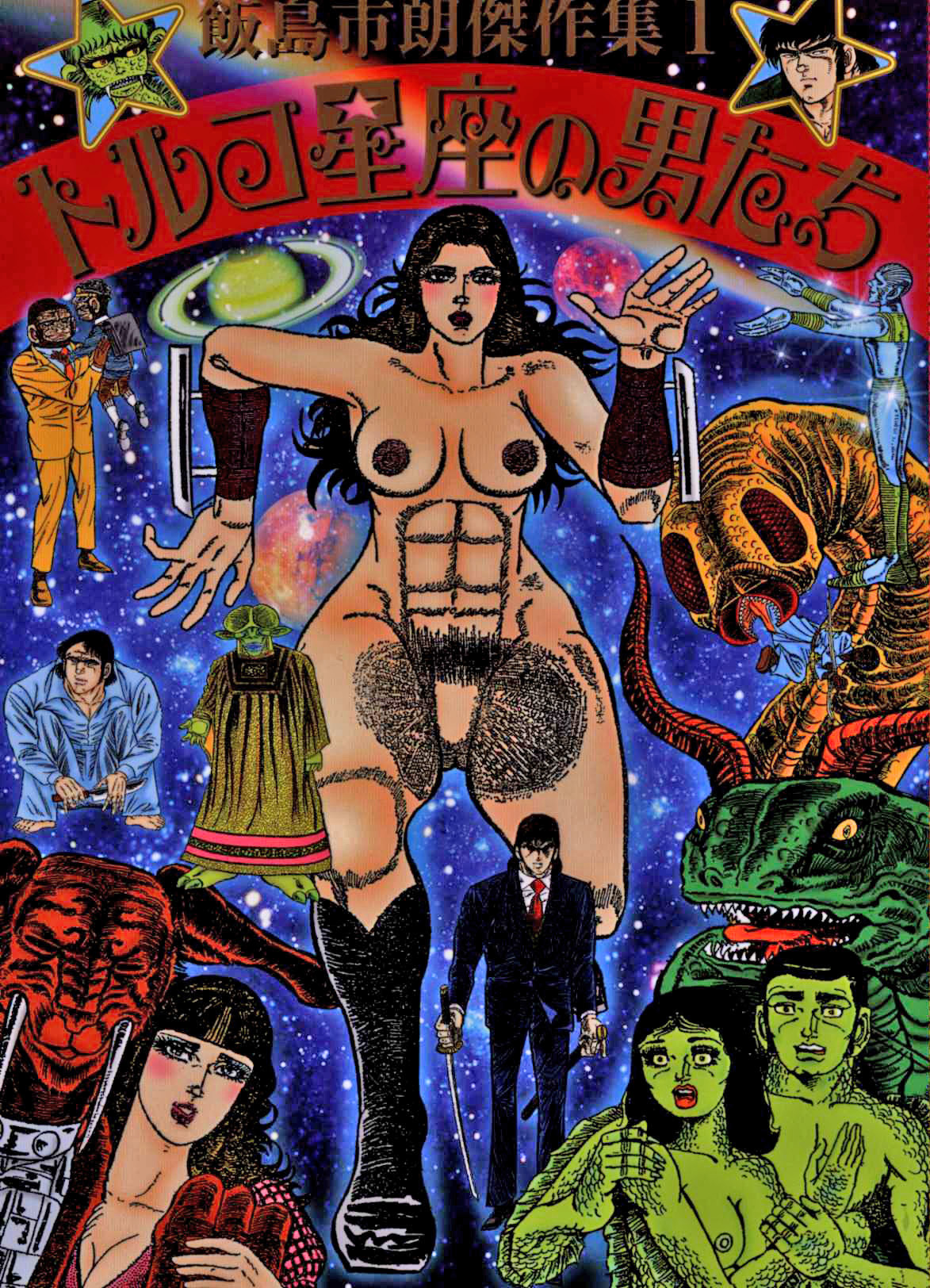

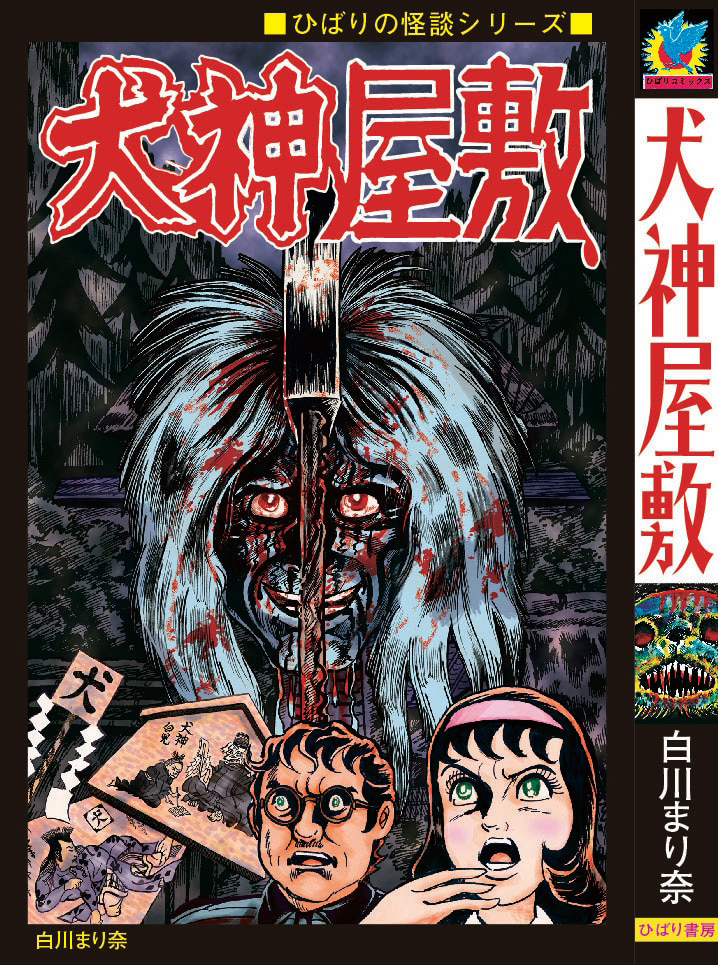

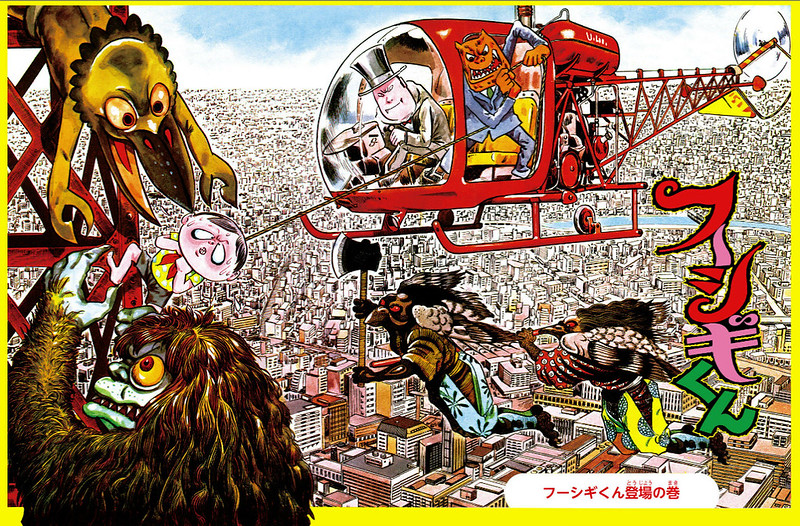

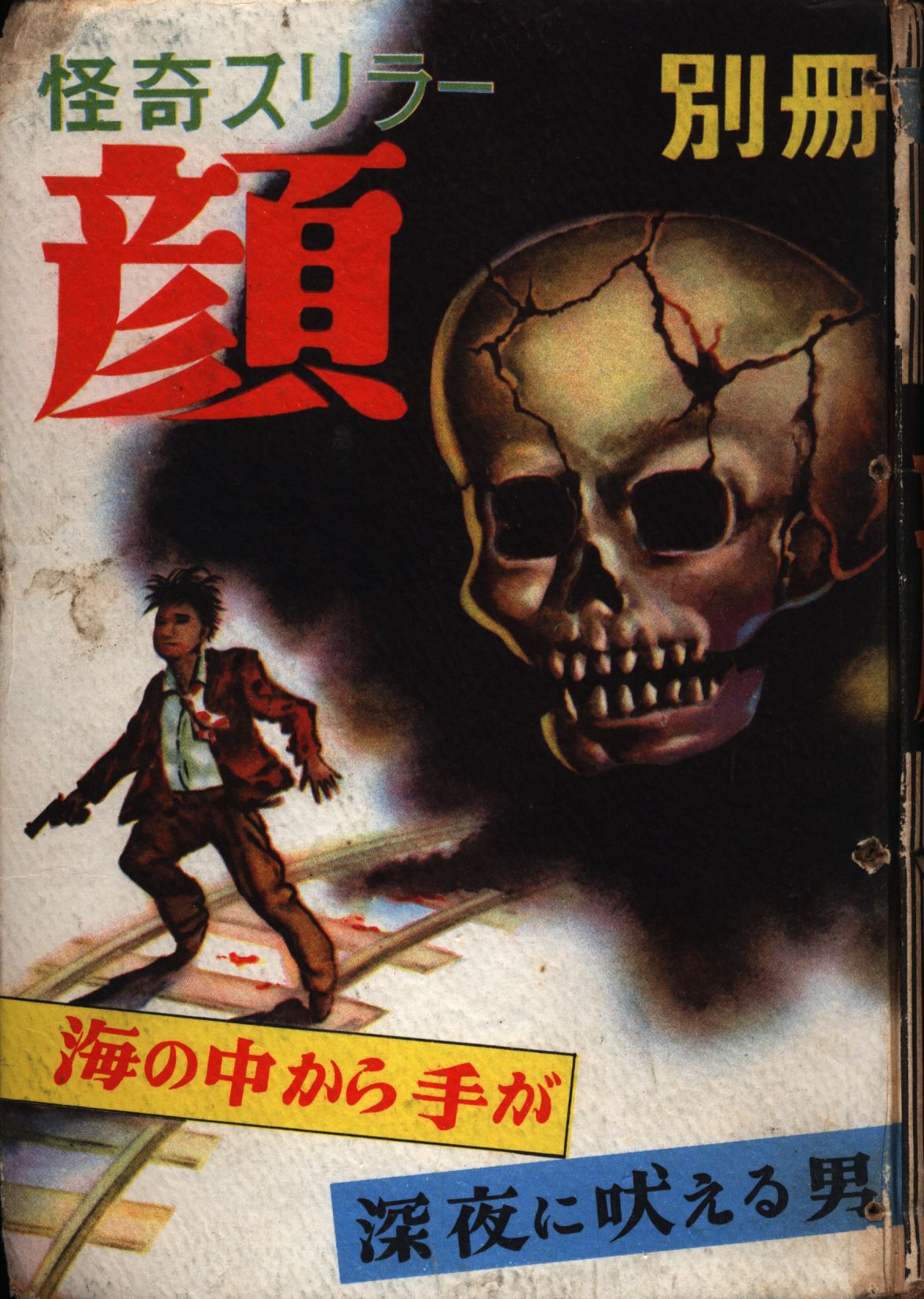

Ichiro Ijima

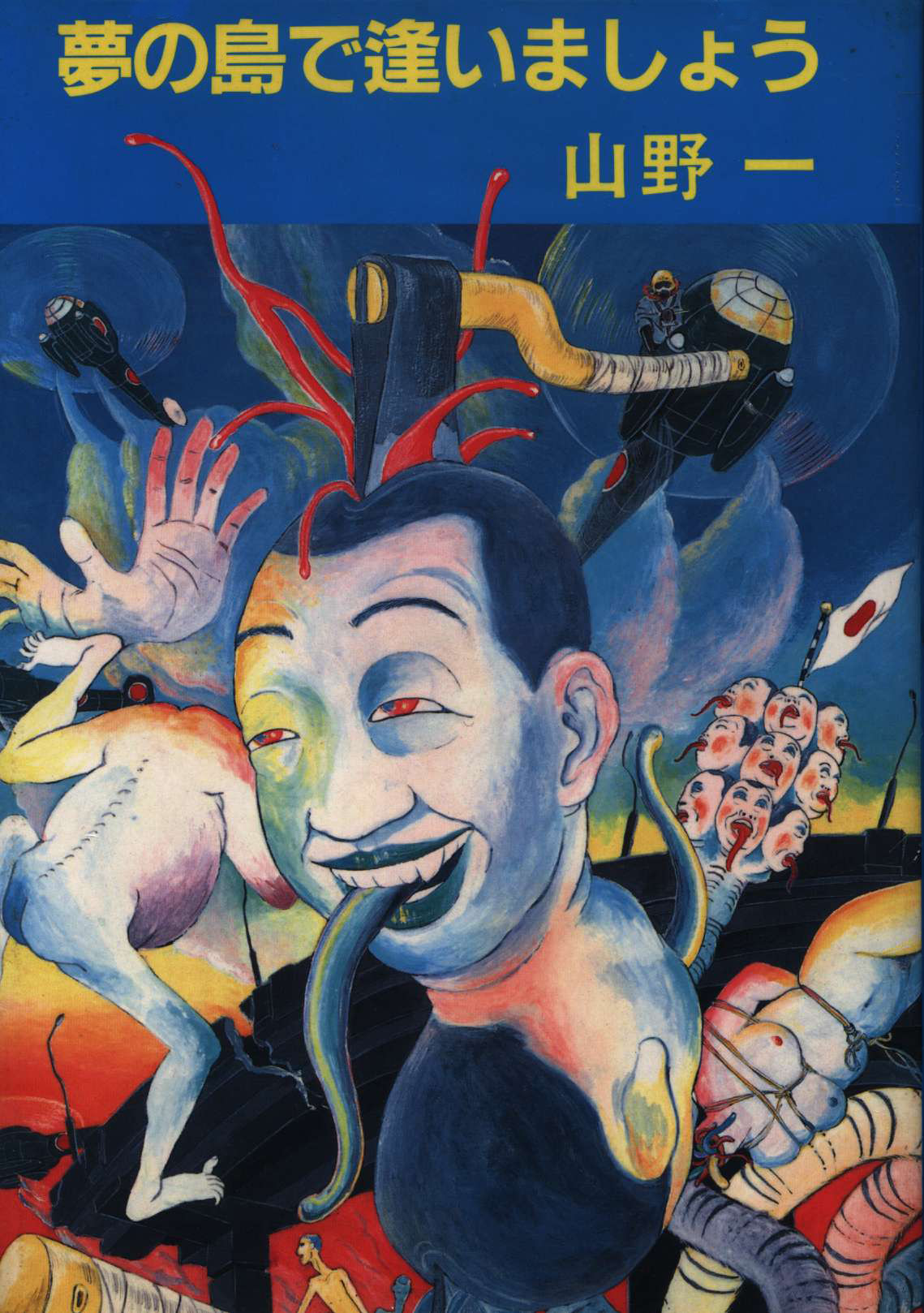

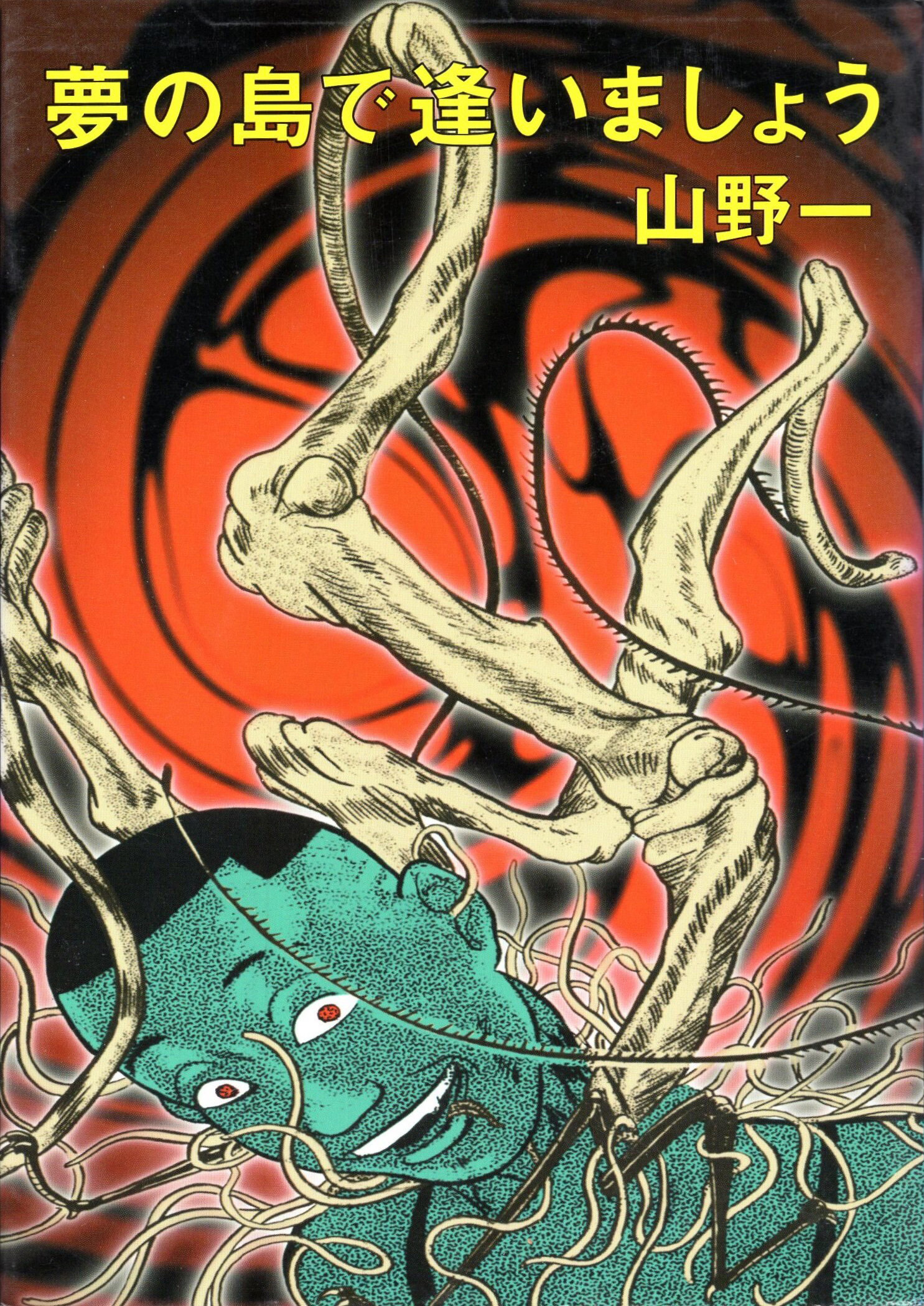

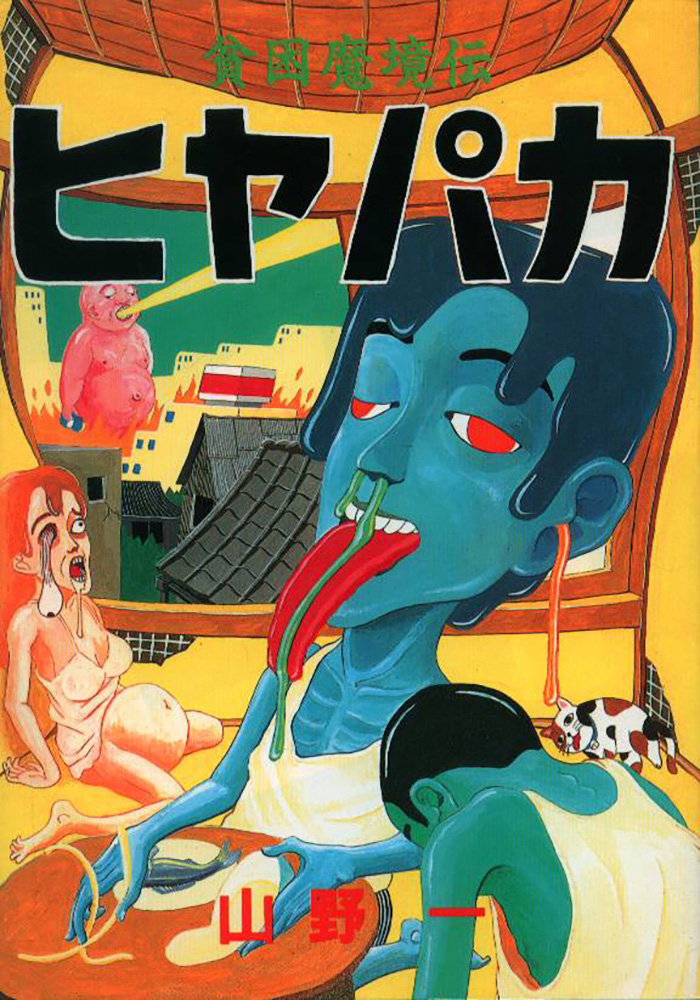

Hajime Yamano

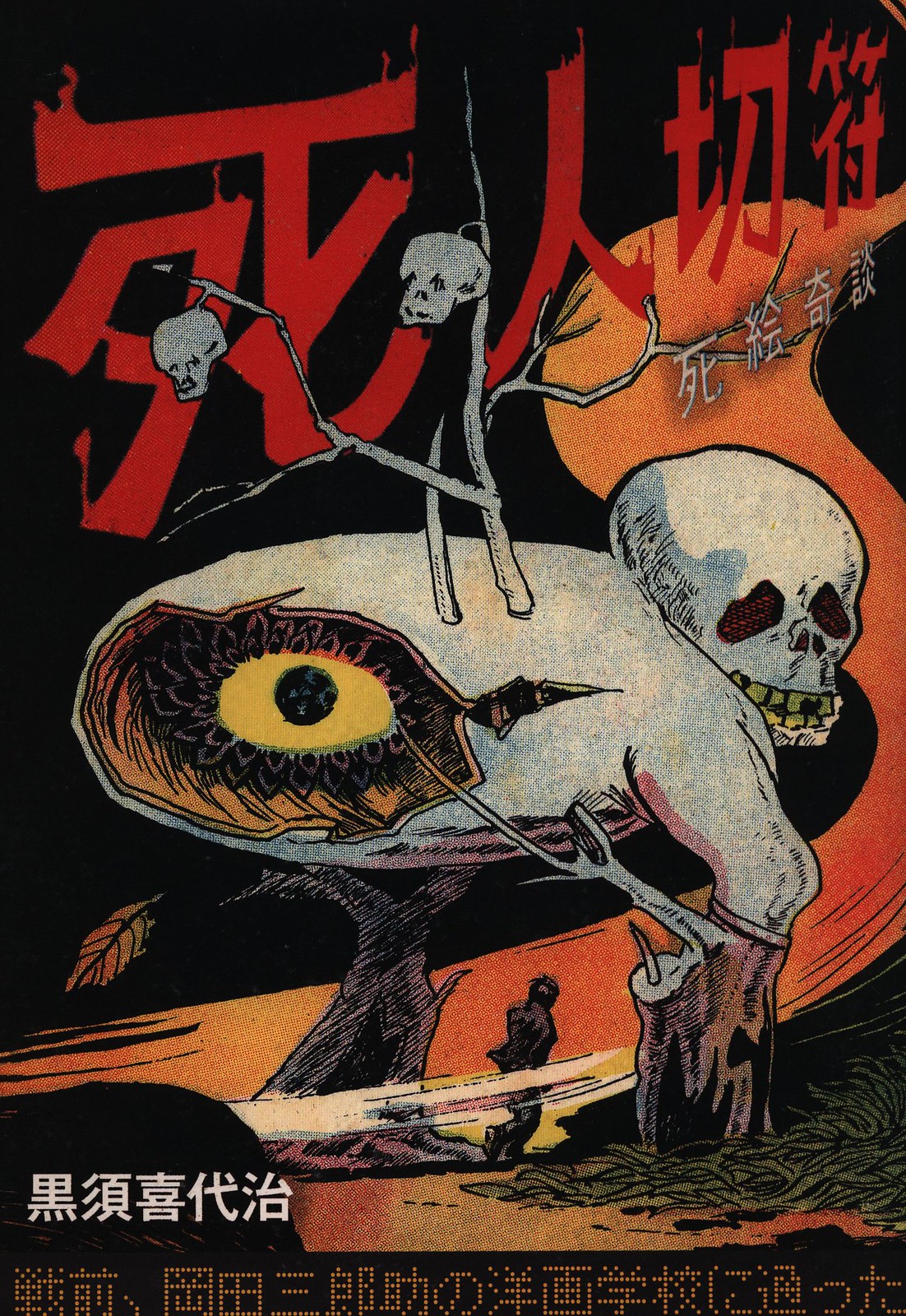

Kiyoji Kurosu

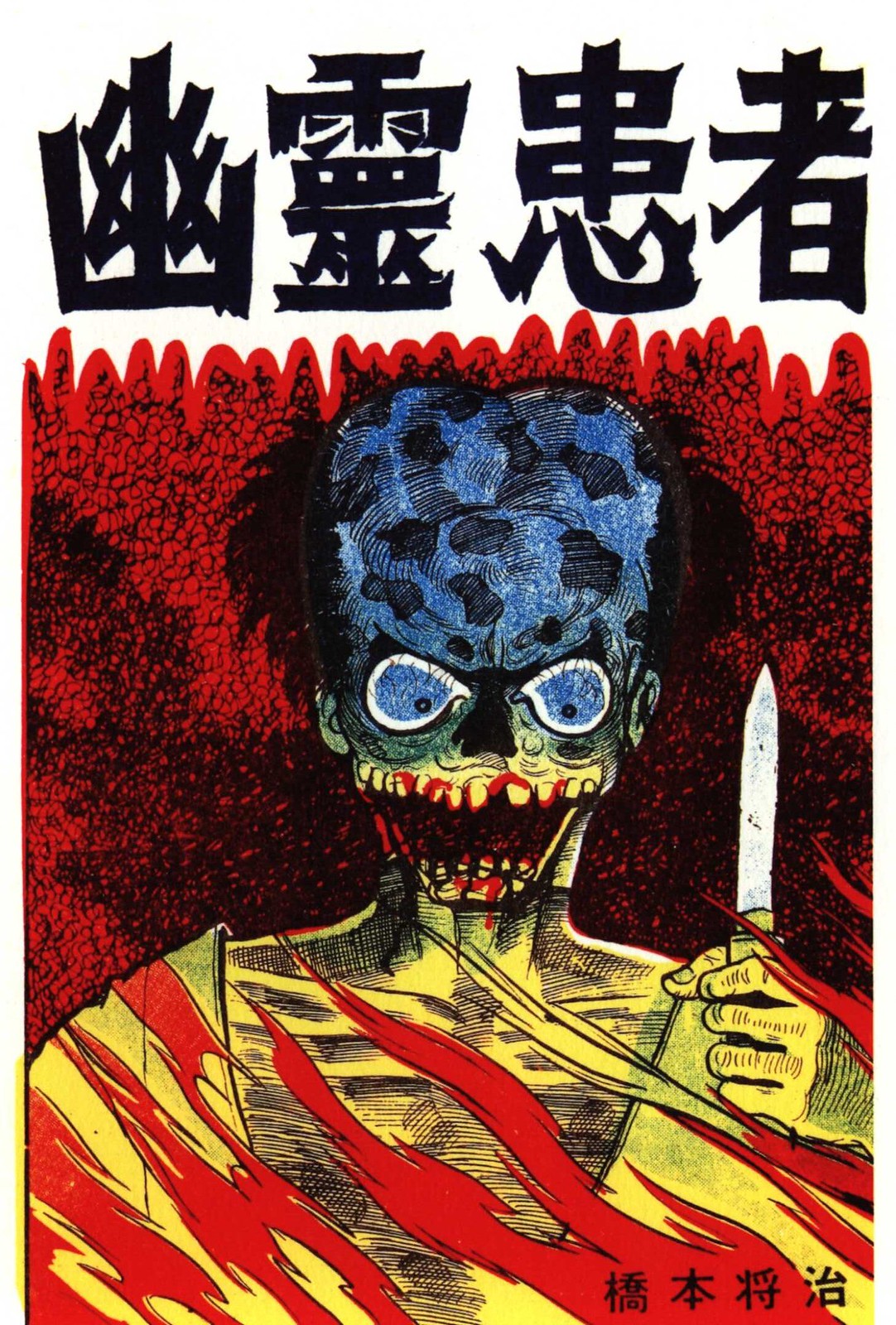

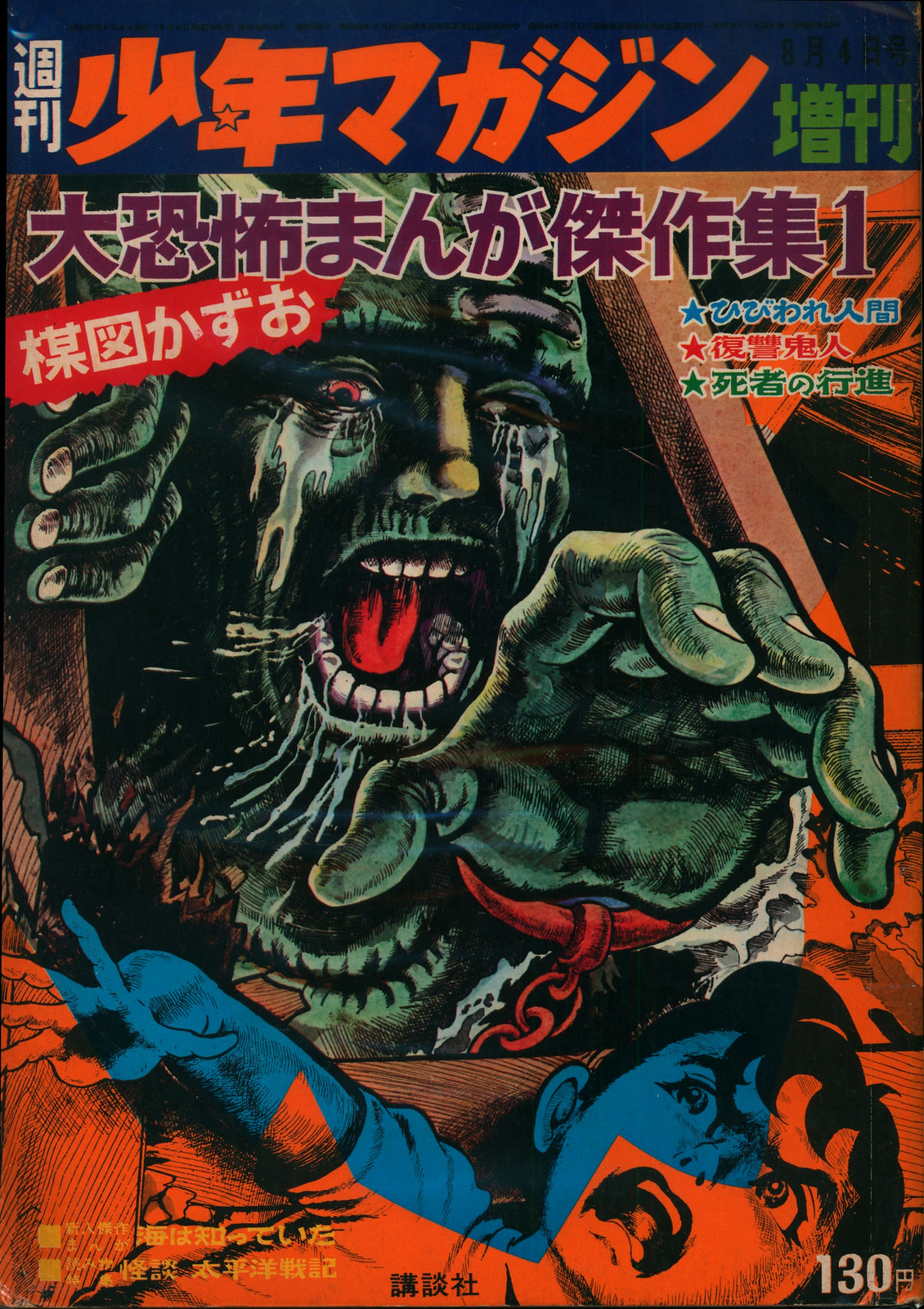

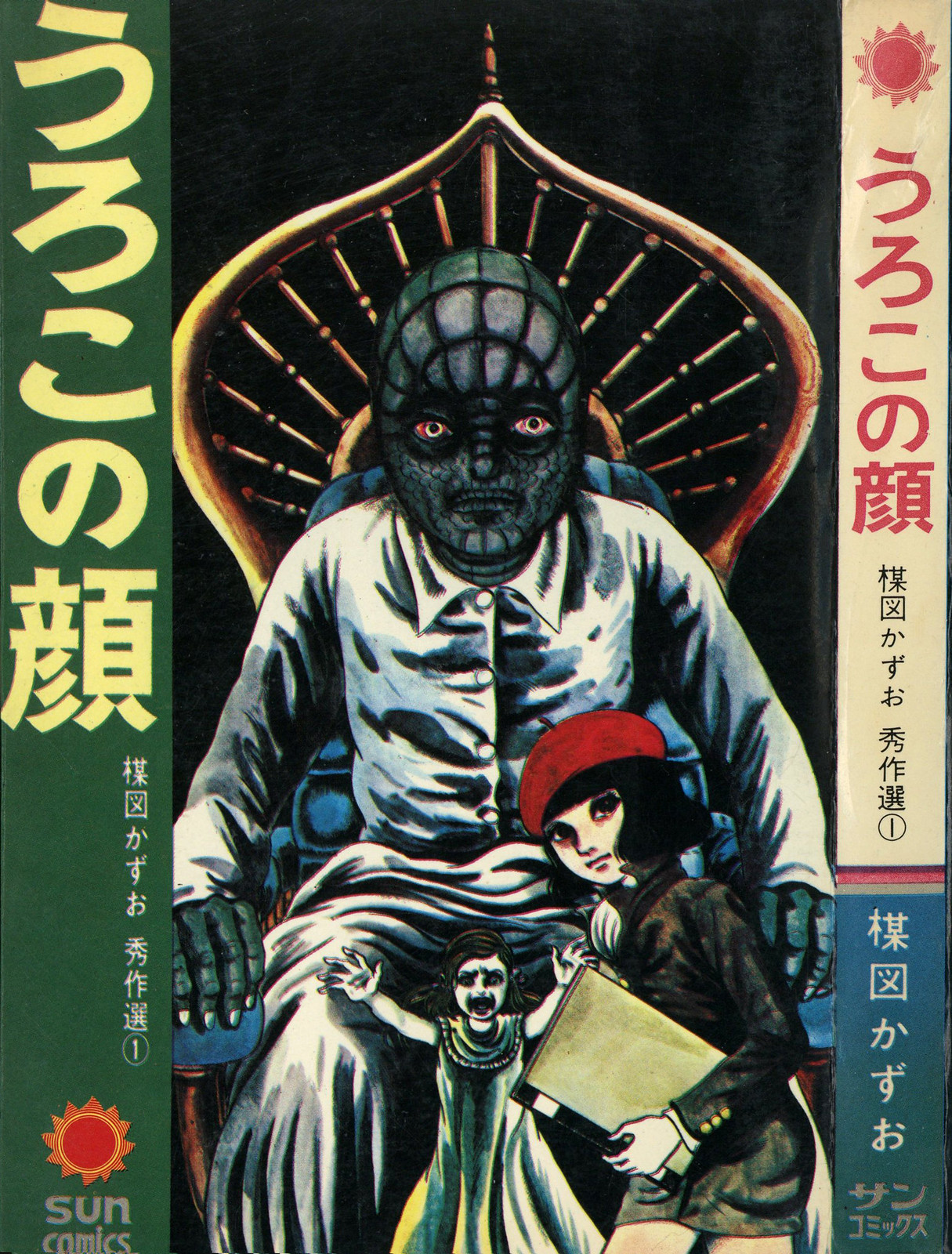

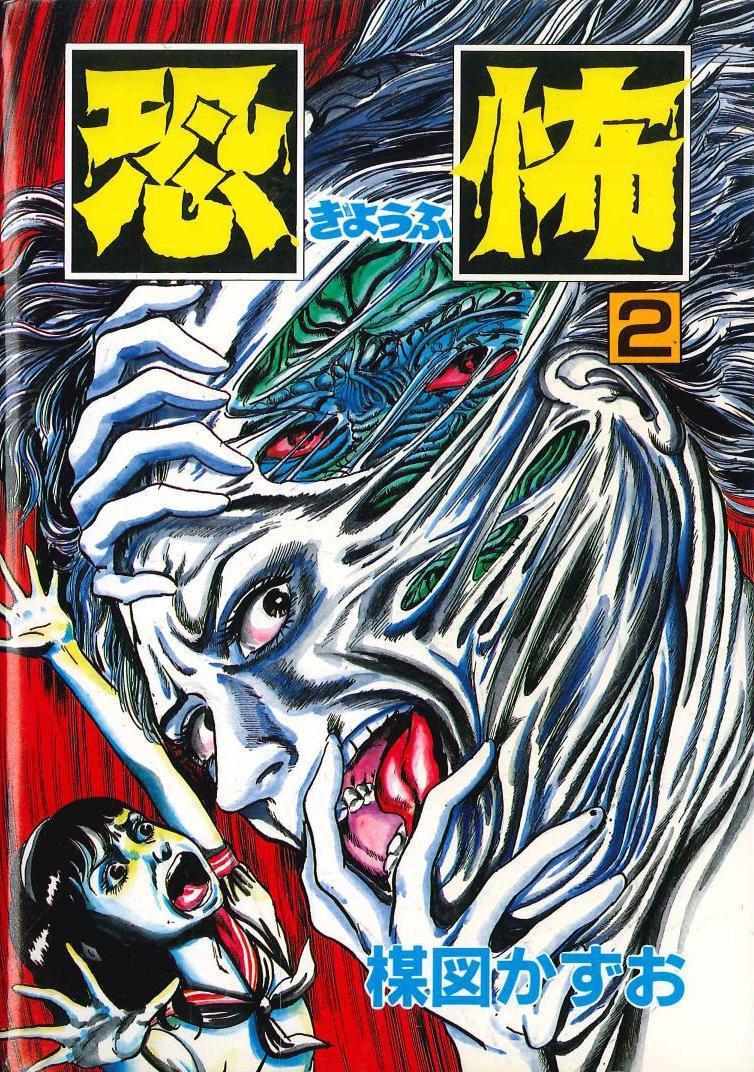

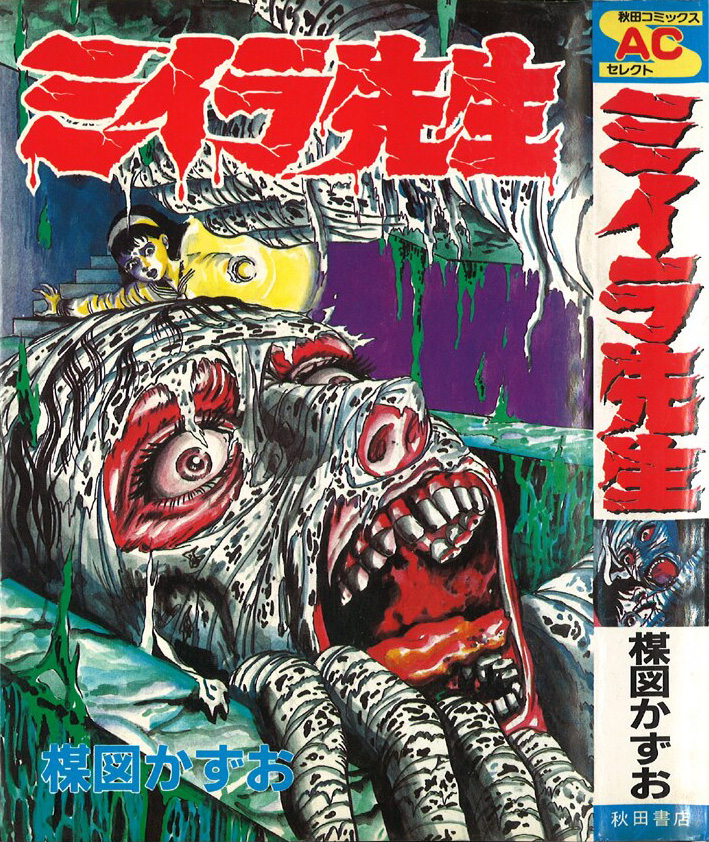

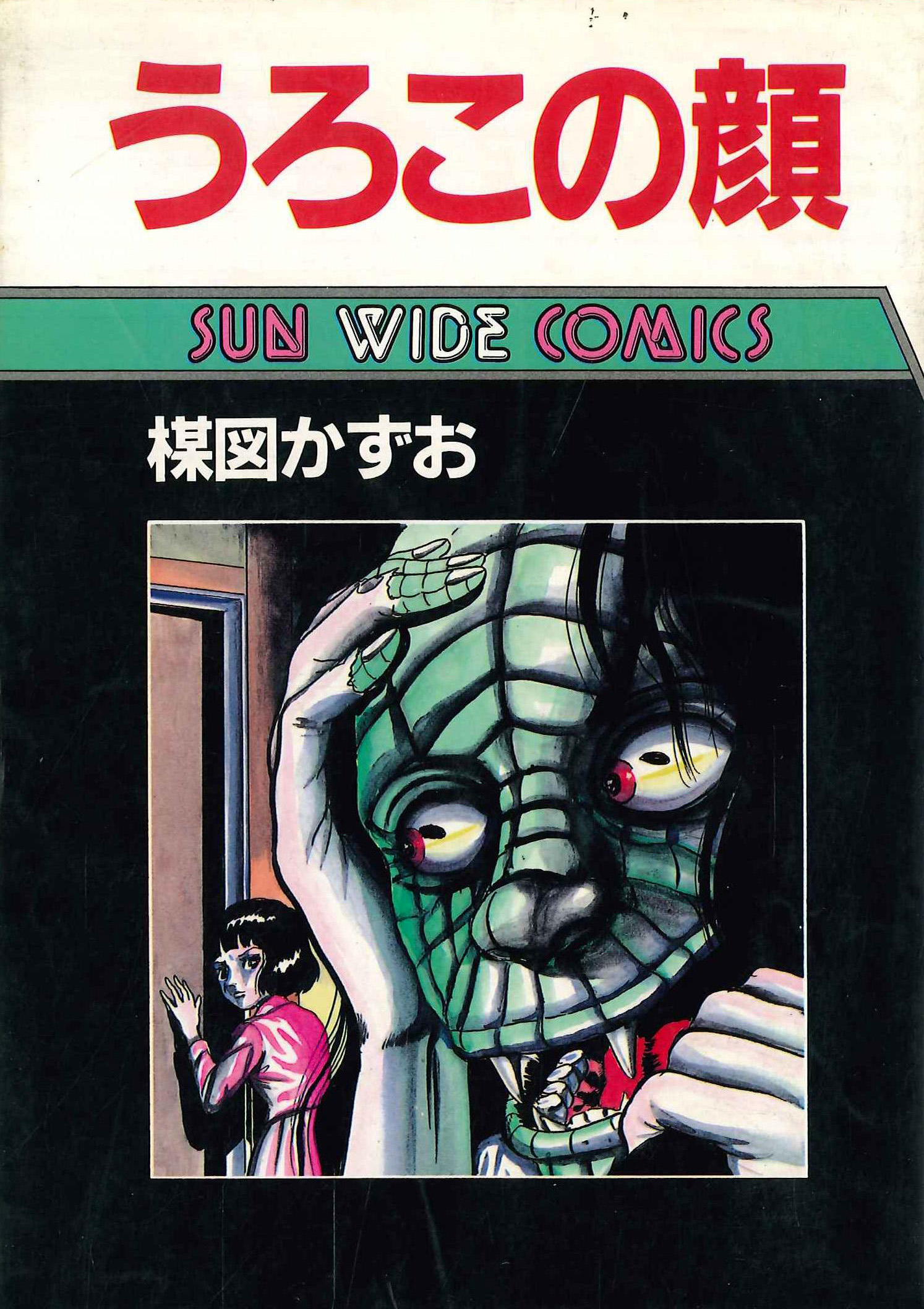

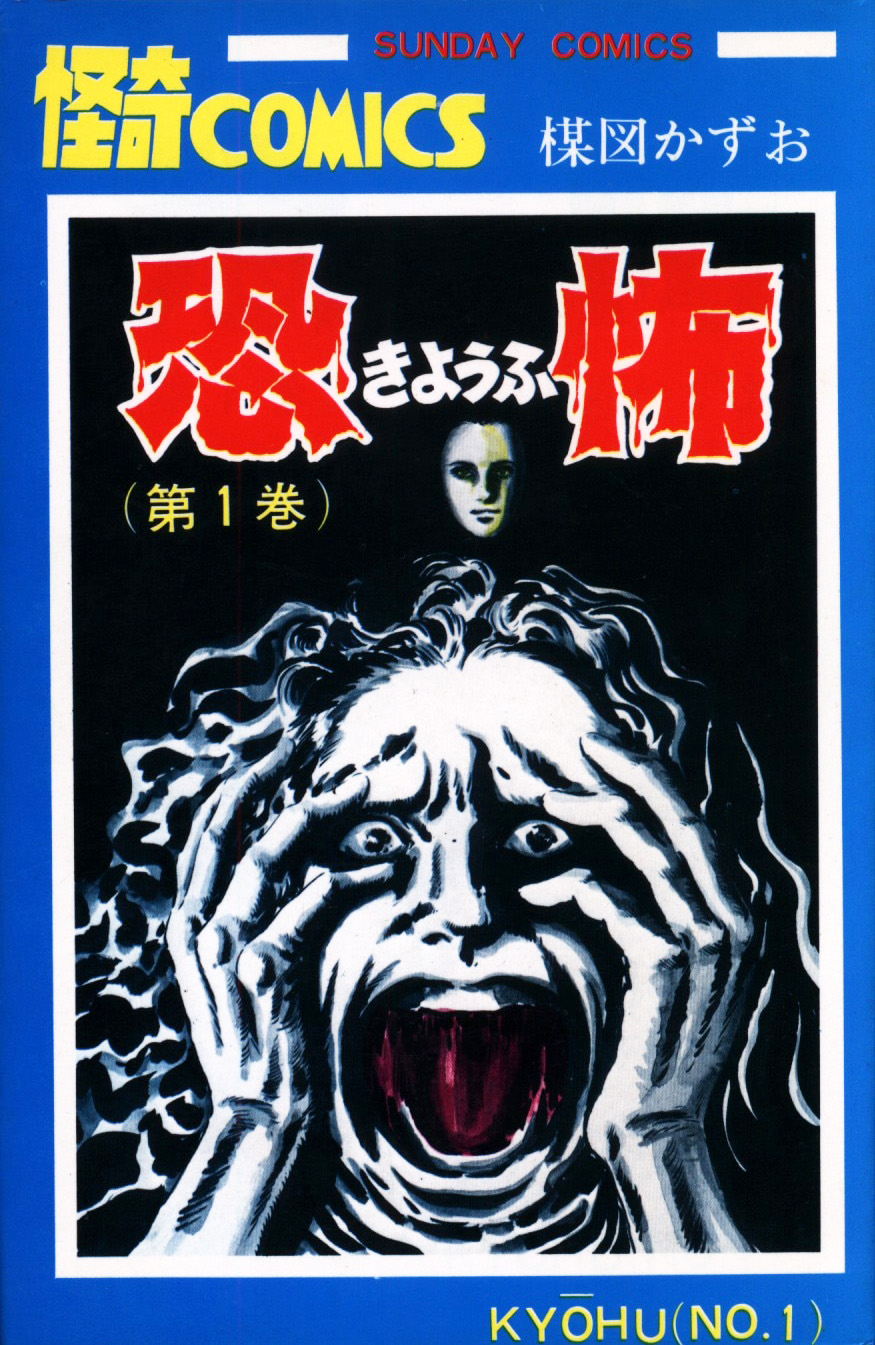

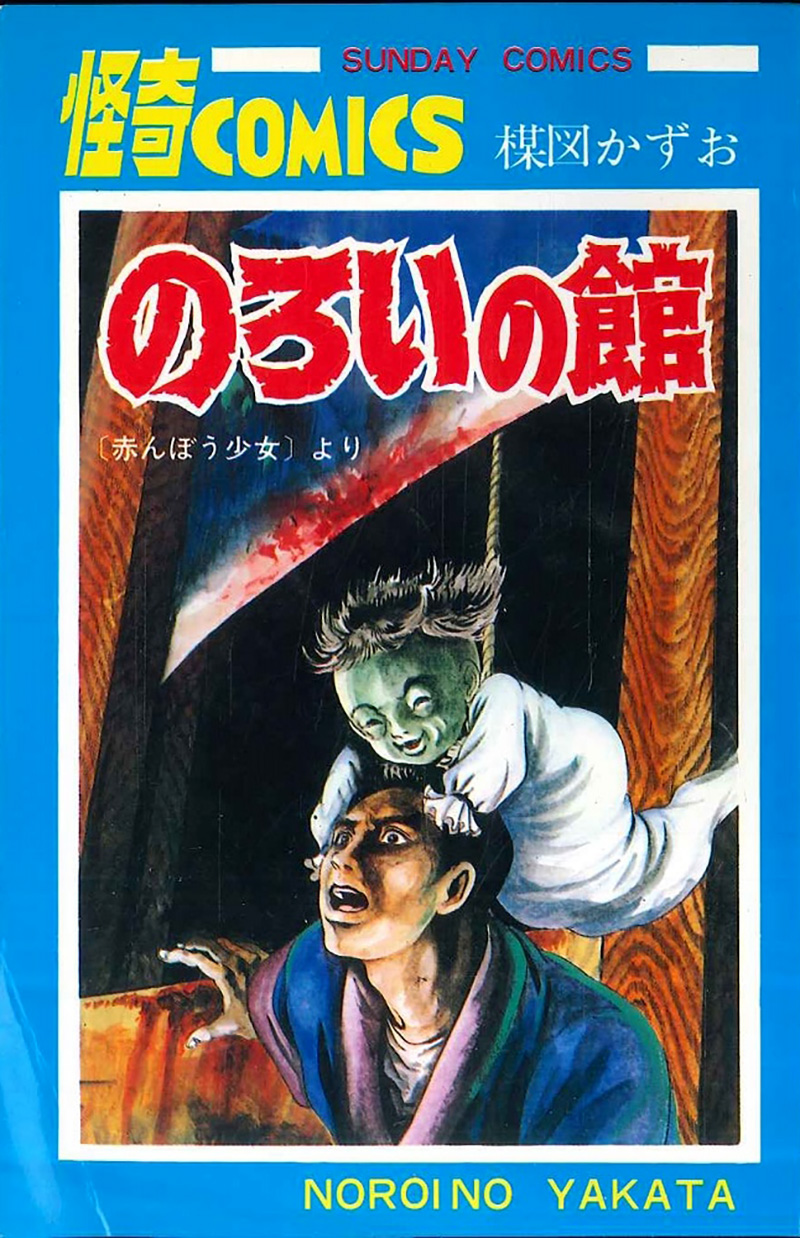

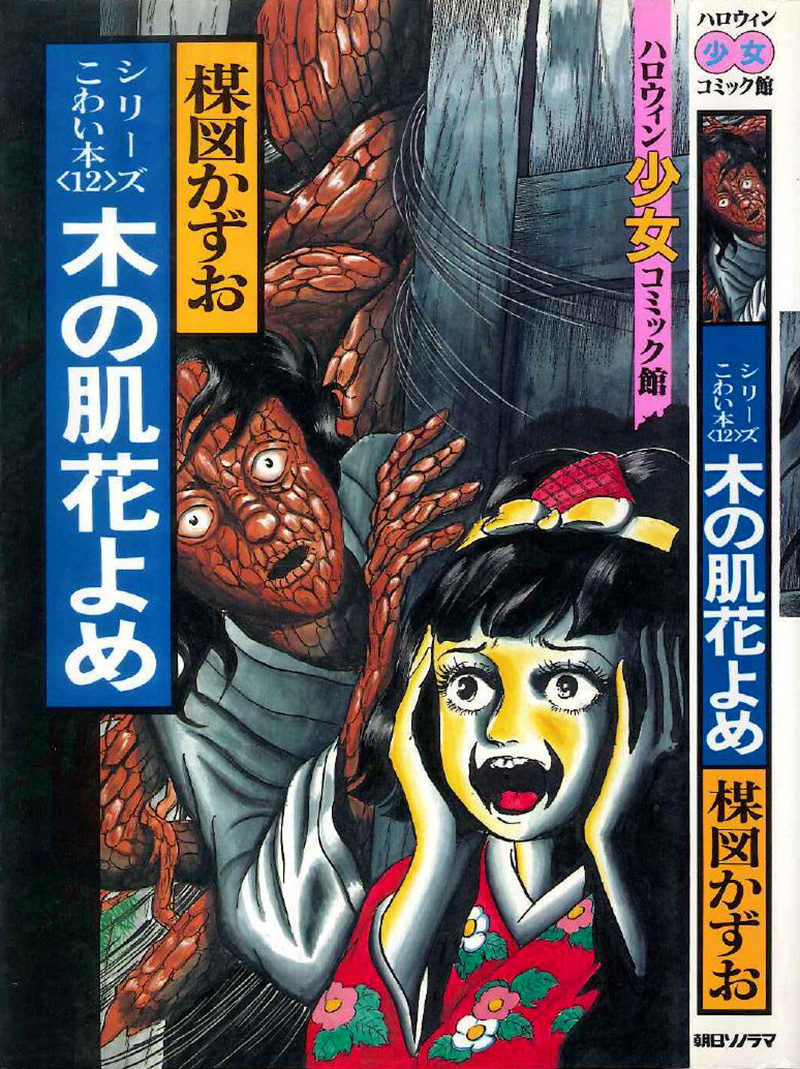

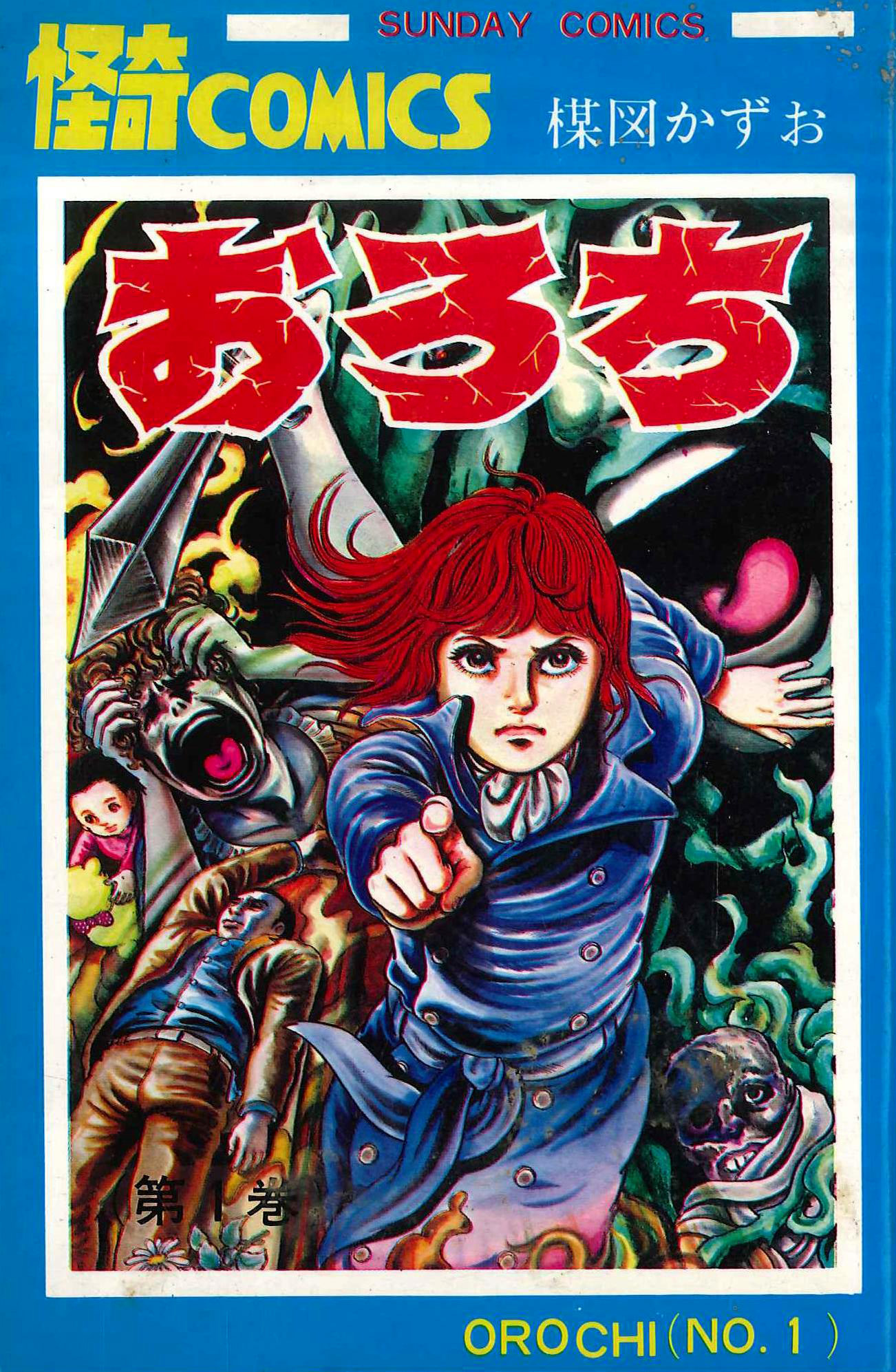

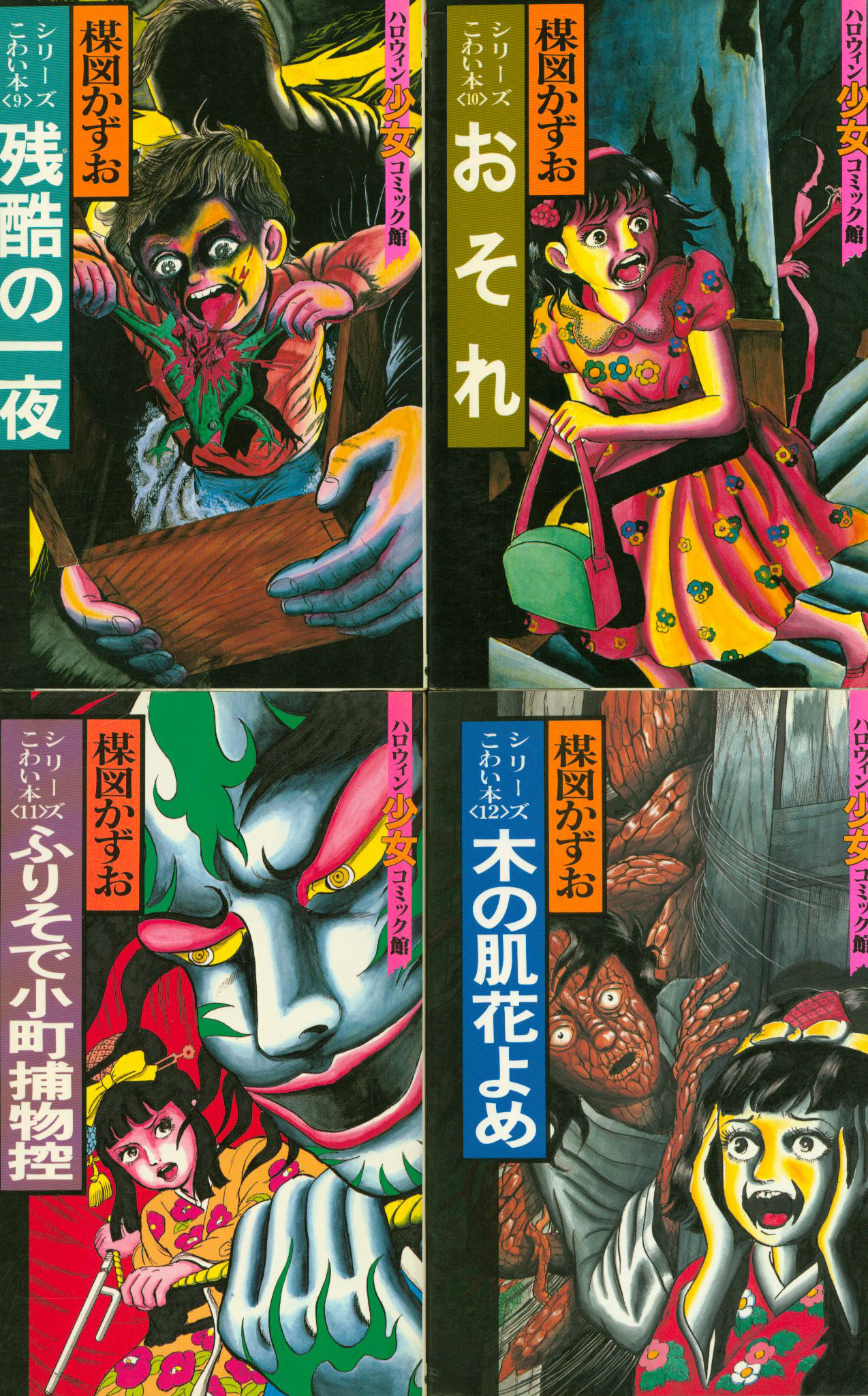

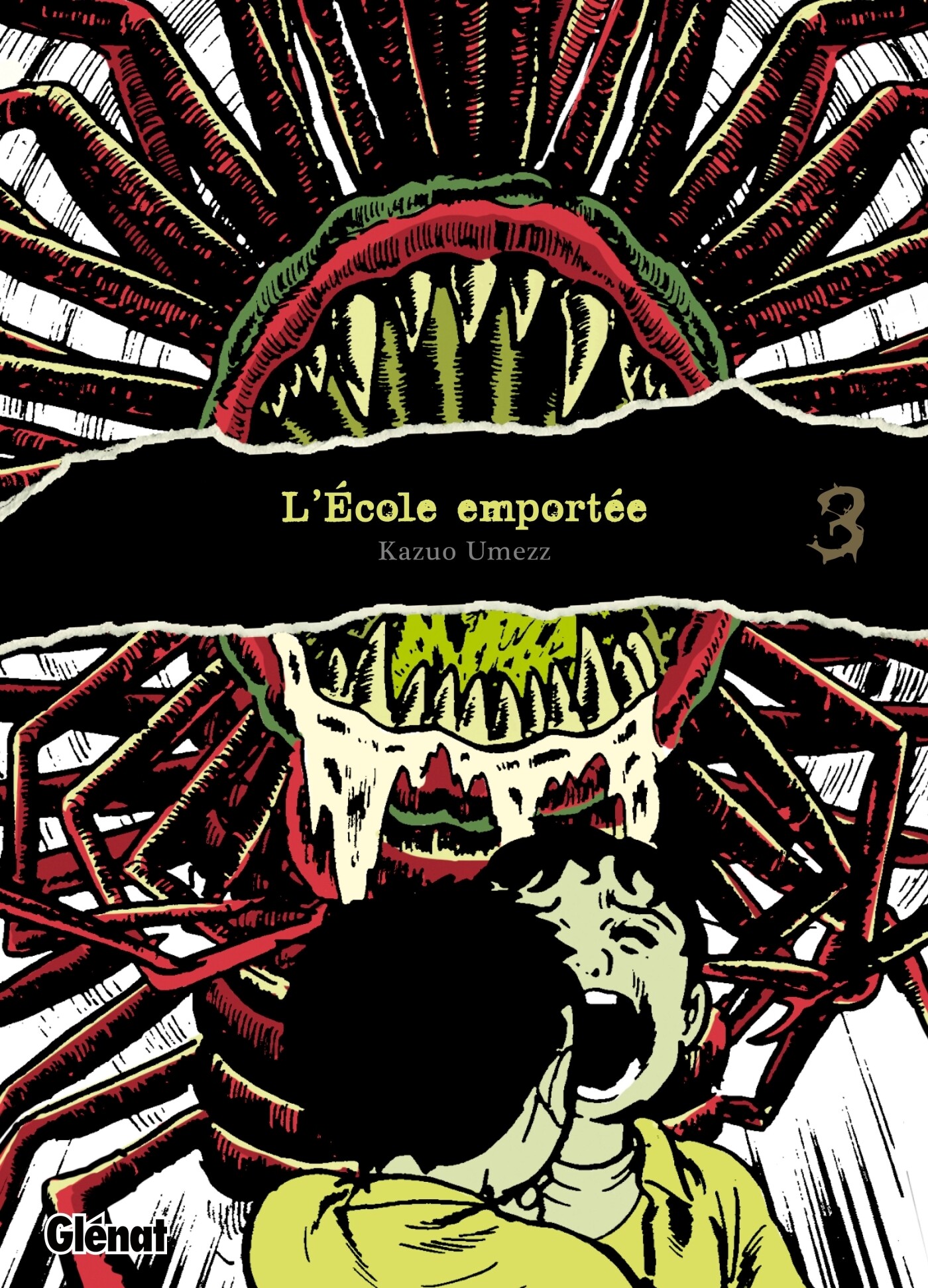

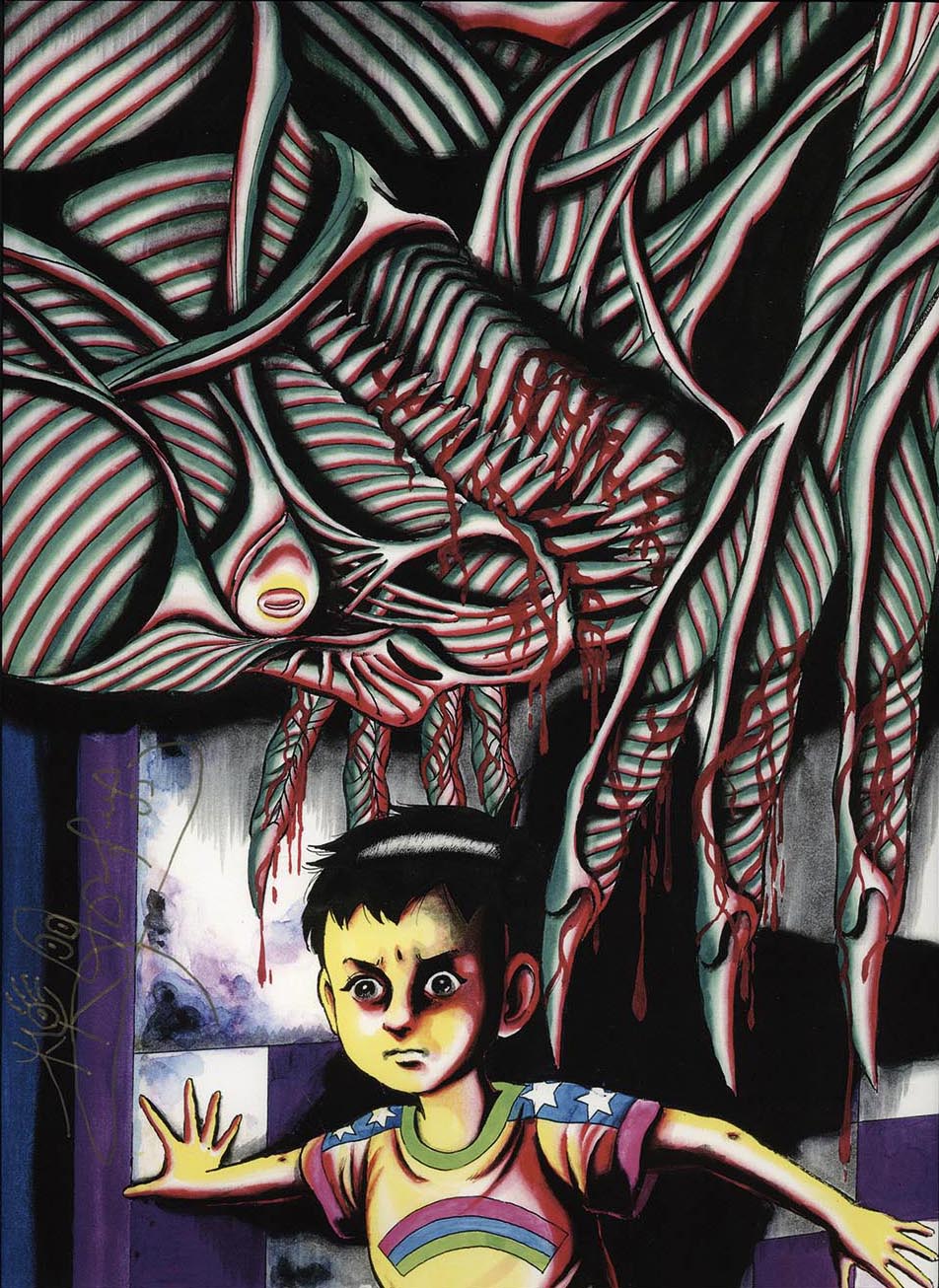

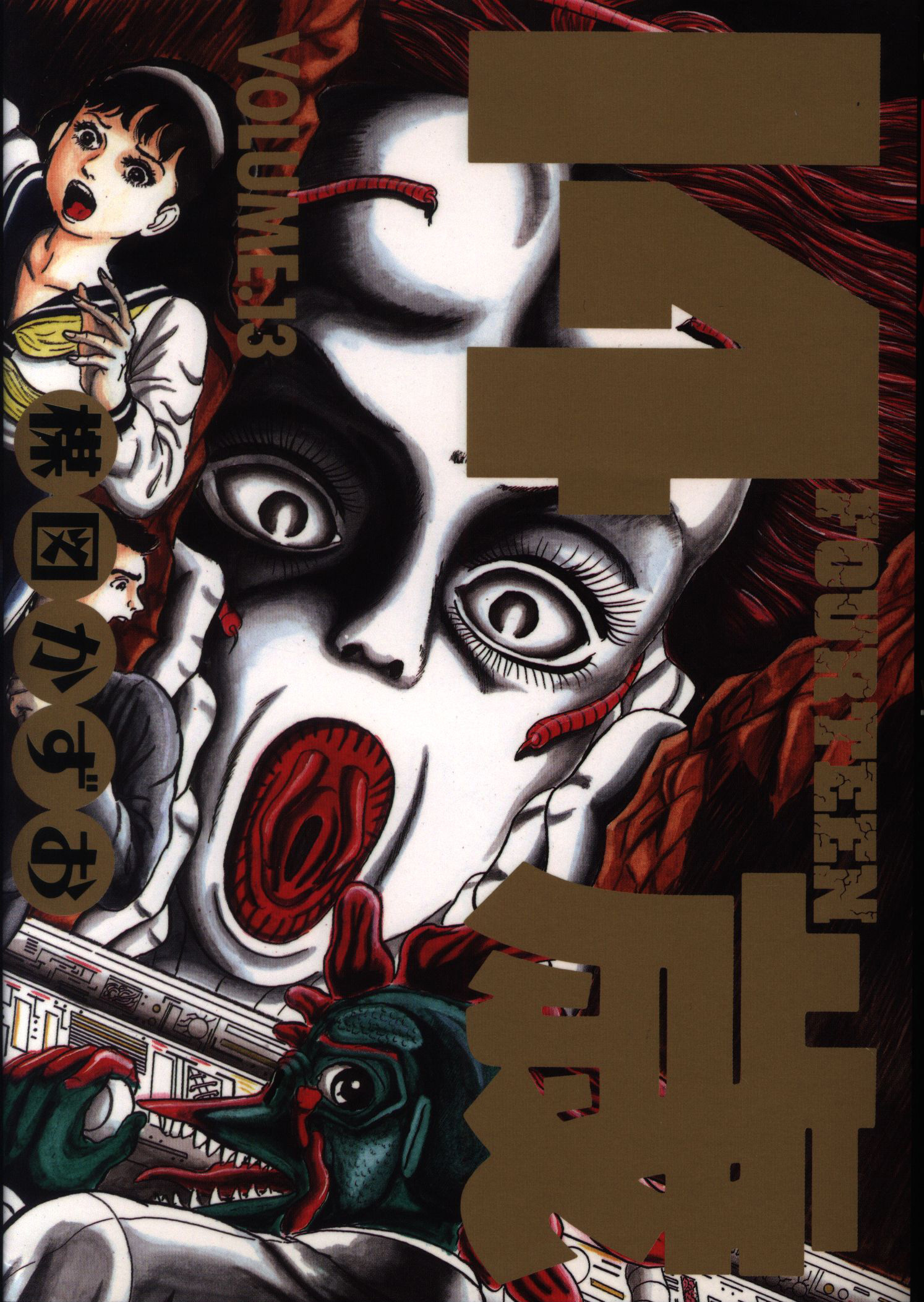

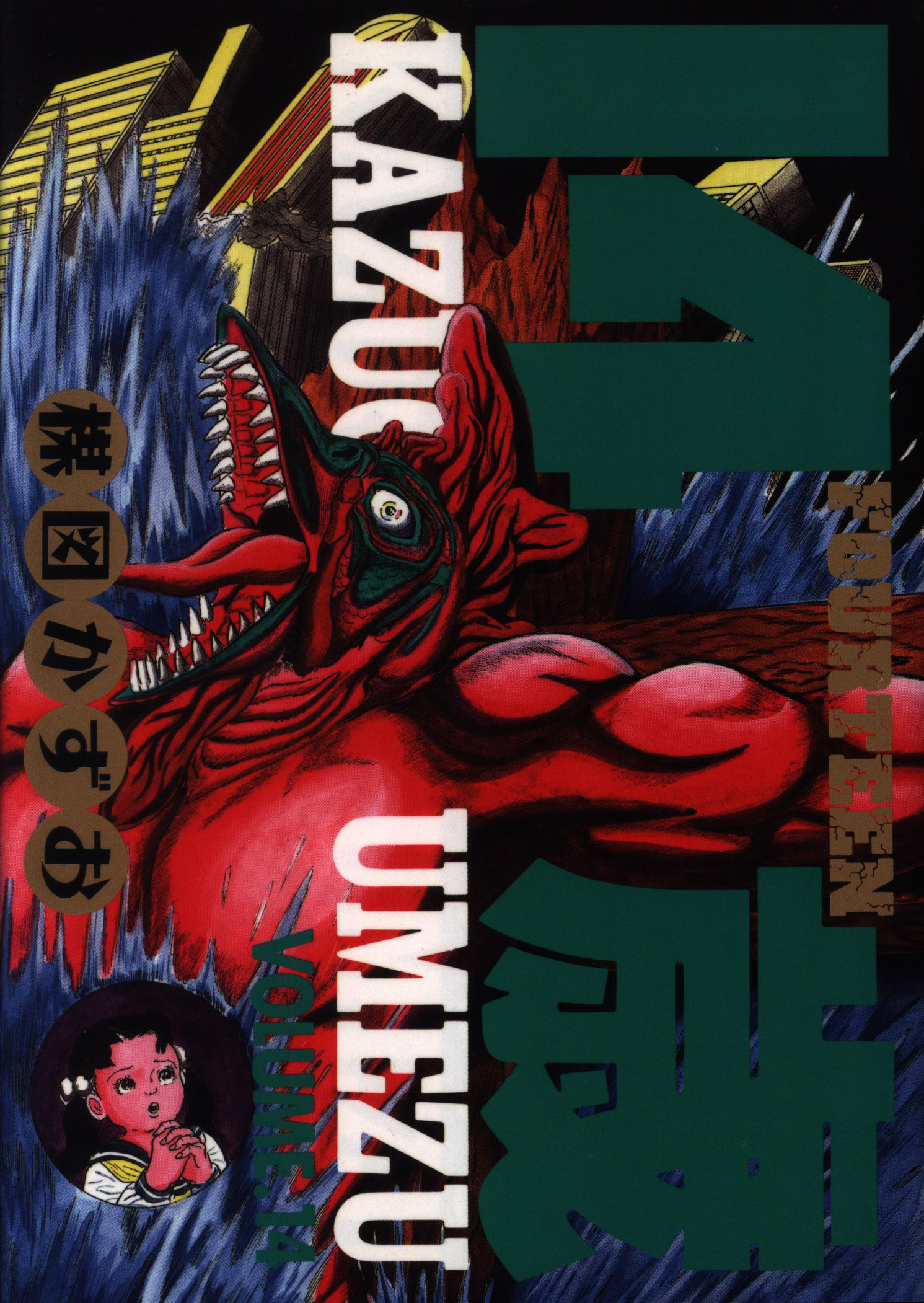

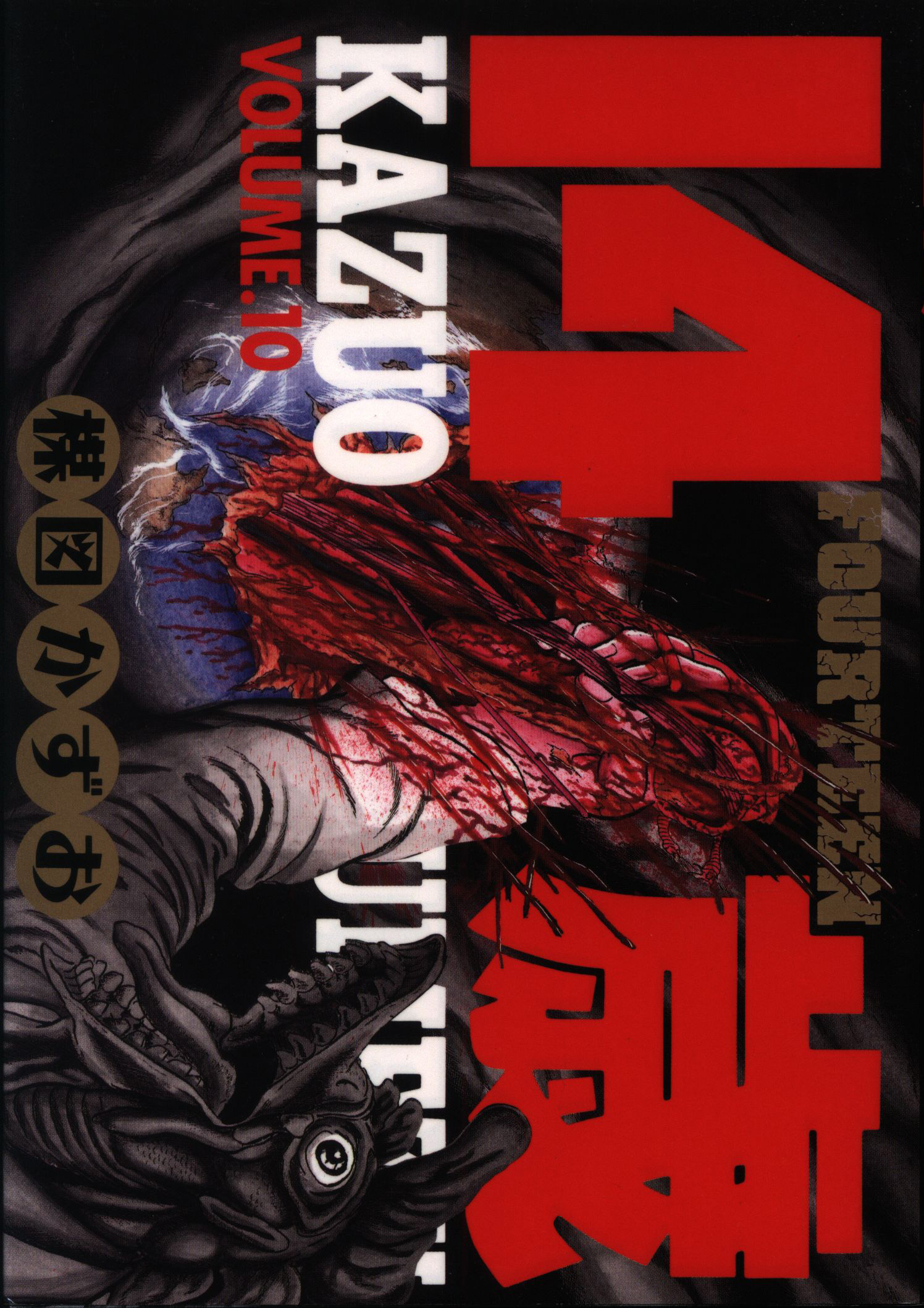

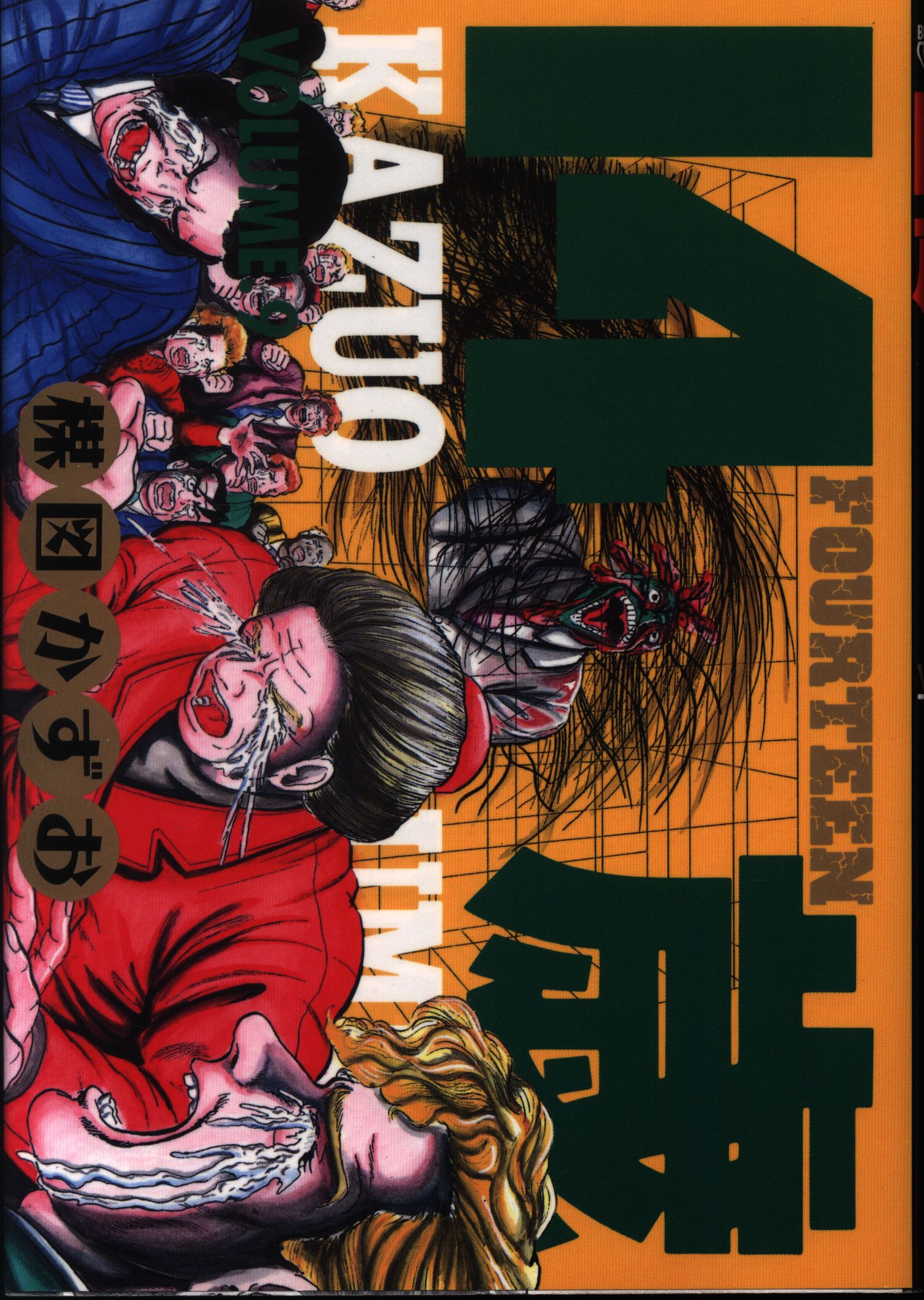

Kazuo Umezu

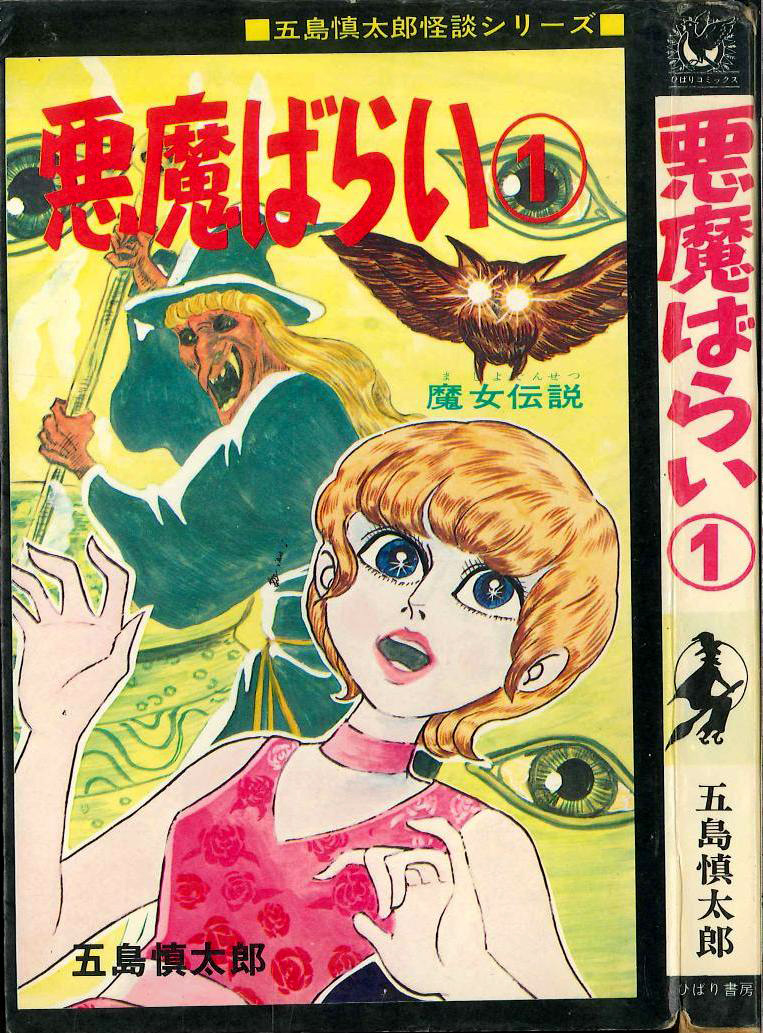

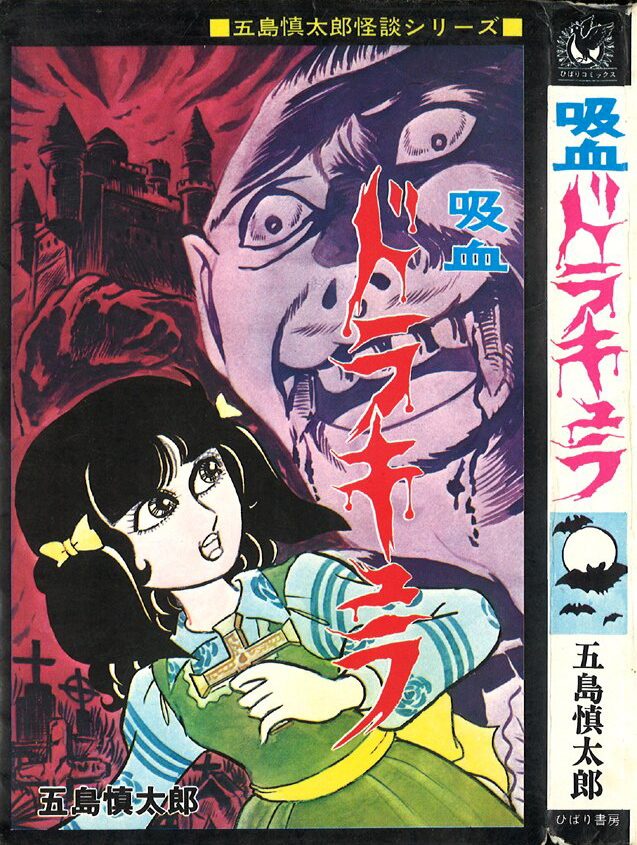

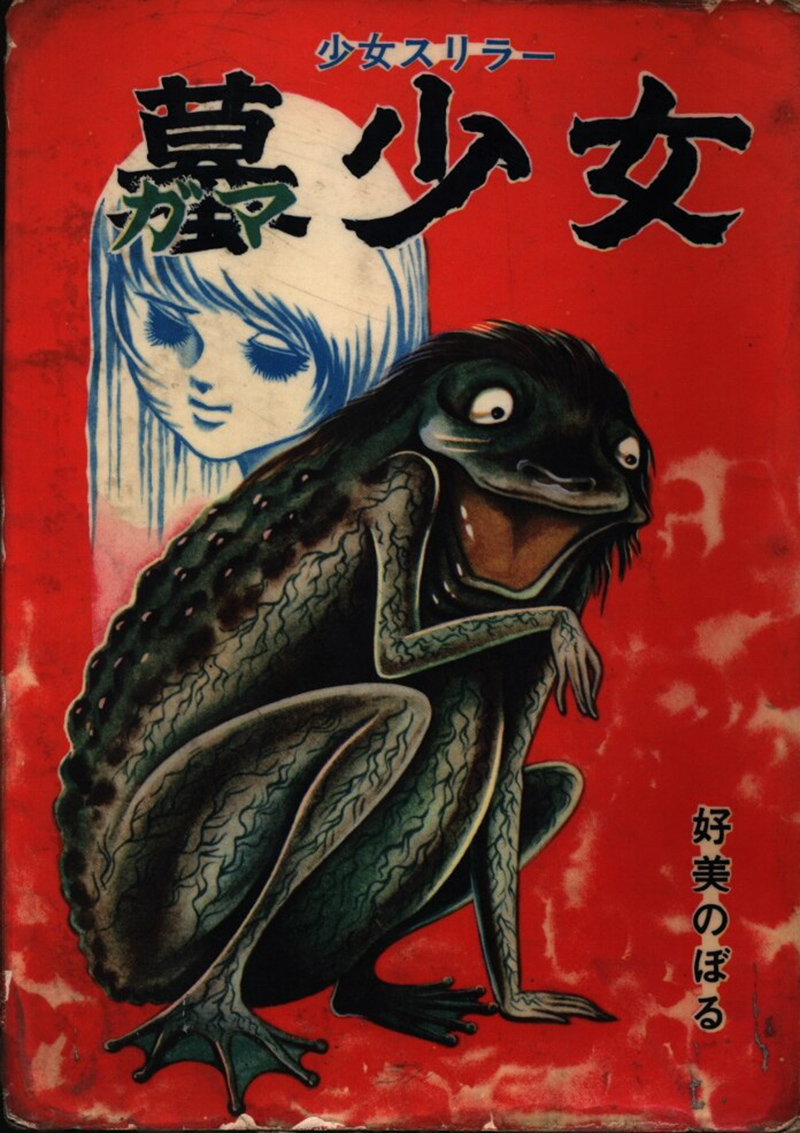

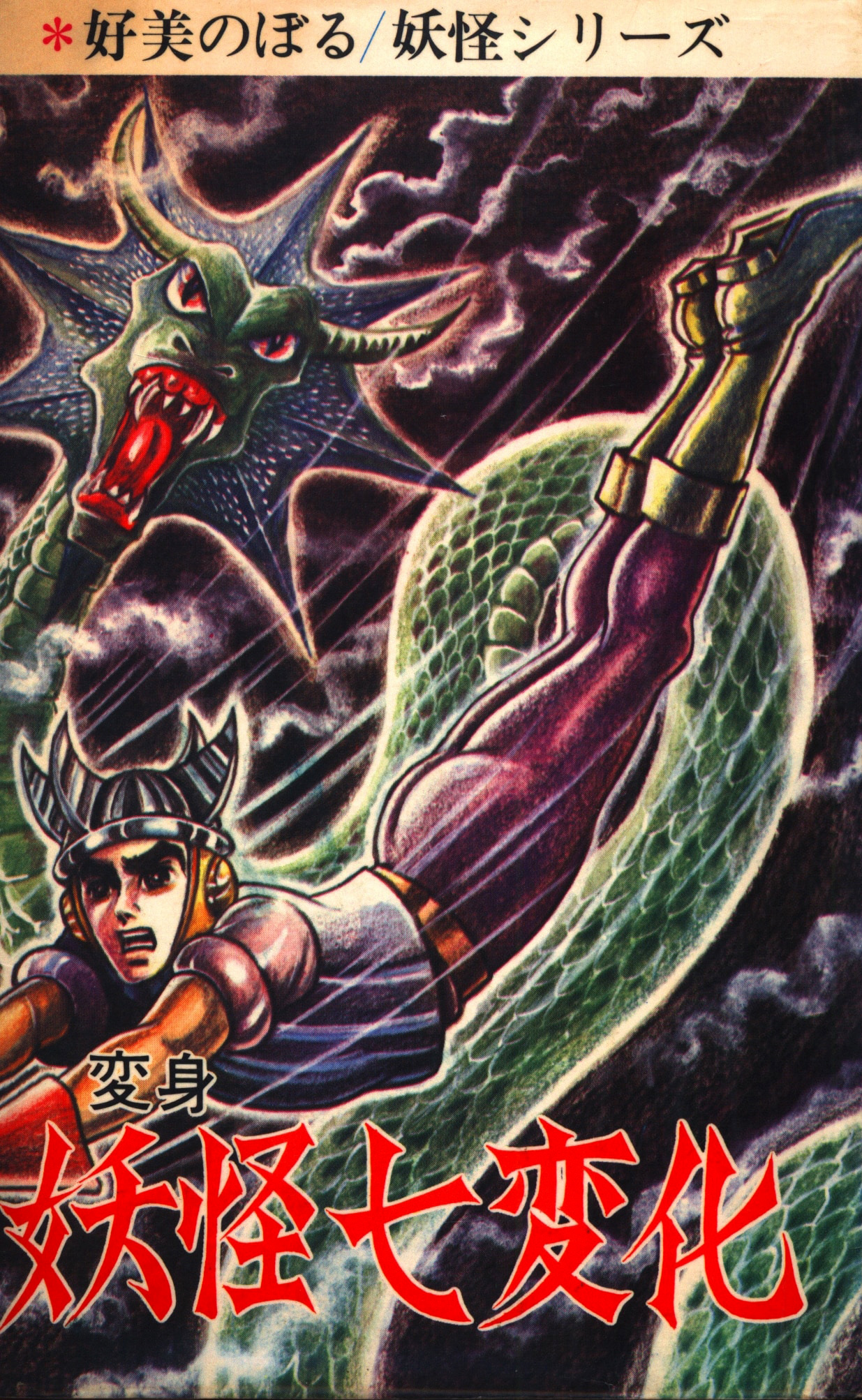

Kazuo Umezu - The Exorcist Comic, 1974

Originally published in the July 7th, 1974 issue of Shonen Sunday, a week before the film's Japanese release.

Originally published in the July 7th, 1974 issue of Shonen Sunday, a week before the film's Japanese release. Umezu previously posted in 2008.