Jonathan Lukens / June 3, 2021

As a young man, I felt that most people conceived of memory differently than I did, believing that failures of memory were errors of playback more than of recording. This idea, that memory works like a vinyl record in which everything we experience has its groove, supposes that it’s just a matter of knowing precisely where to put the needle down to replay the experience. In contrast, my younger self operated with the also erroneous belief that our memories are only hazy recordings of what we have somehow deemed worthy of recalling—that memory is like finding old semi-legible notes to ourselves written in an old notebook and trying to figure out what they mean.

It was with this theory of memory in mind that I had begun to consider Split, a movie that I thought I remembered renting from a video store up the street from my childhood home sometime around 1990. For over a decade, my occasional recollections of the film, often spaced years apart, might prompt a web search with no results, which would then introduce a sense of disorientation: I could not experience the instant gratification of finding some online mention that might confirm that what I remembered was real. Was Split (that was the name, right?) just an Easter Egg written into the script of my past—some sort of Berenstain (sic?) Bears thing? After all, and with all due respect to the films’ creators: if my adolescent mind was going to fabricate a memory, this is the sort of thing it would have come up with.

Originally released theatrically in 1989, and subsequently on VHS in 1991 by Futura Home Video, Split was reissued on DVD in 2018 by Verboden Video and is also available through Alamo Drafthouse’s streaming app, which is how I was able to confirm its existence and watch it again. Spoilers of the film follow, but only insofar as my synopsis is veridical to the plot—a nested disclaimer I wouldn’t need to make if the film were less fractured. Whether its cracked mirror nature is a deliberate mindfuck, the result of freshman filmmaking hamfistedness, or both, is not something I can tell you.

The film opens with Starker, our hero, wandering the streets of San Francisco. His ripped jeans show his bare rear end, and he’s wearing the sort of jagged and discolored false teeth that might have been advertised in old comic books alongside fake vomit and squirting flowers. He walks through a parking lot full of city buses, suddenly looking directly at the camera and yelling, “Stop following me. Leave me alone.” At first, we believe he is addressing us, the viewers, and breaking the fourth wall, but the camera cuts to two men dressed in a mid-‘80s Ivy League casual style—like they just walked out of a JC Penny catalog shoot. One sits at a computer; the other, older and mustachioed, is framed over his right shoulder. The younger man was surveilling Starker, and, as the dialogue reveals, the populace more broadly. He rewinds a recording of Starker’s camera-facing monologue and consults with the older agent, who says Starker is just crazy, but capitulates to the younger agent’s desire for further observation.

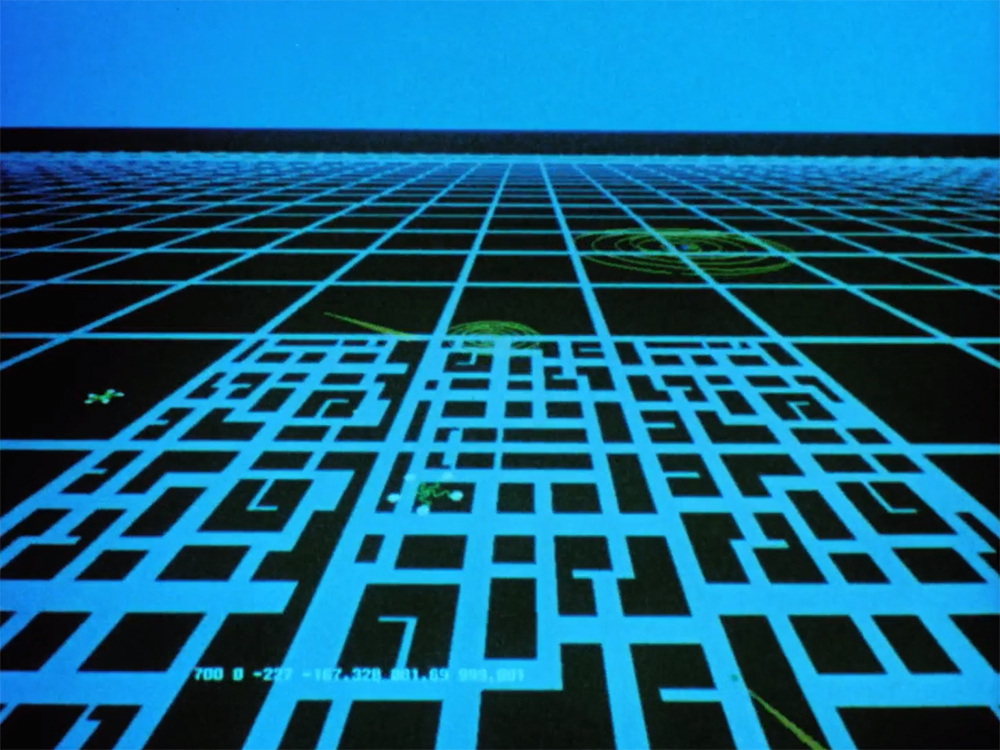

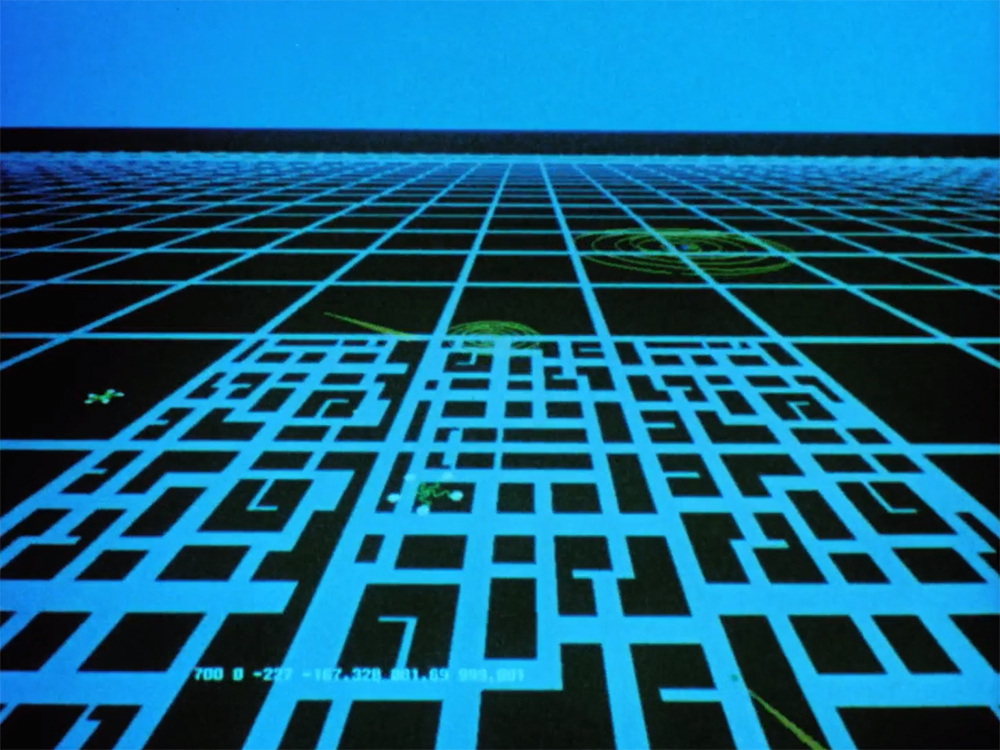

They run a face recognition program, presented as a musical montage, in which we see Starker’s head rendered as a 3D model as the camera hops around a black and white grid of similar hairless heads looking for a match. The sequence is still enthralling and somewhat hypnotic after 30 years. This isn’t a real 3D scan of a human head; rather it’s a painstakingly created proof of concept showing us what the technology that would soon become ubiquitous might look like. It dances. We hear pitch-shifted human voices of the sort we might associate with Laurie Anderson’s “O Superman,” and they create a synthetic and escalating harmonic pattern as the facial recognition nears completion.

This is the first of a few similarly rendered and soundtracked scenes that make Split worth more attention than it will ever receive. Analog processes are used to pre-mediate future digital operations, and there is a lo-fi poetry to them. These skies are the color of the ancestors of our flat-screen TVs, their saturations and frequency roll-off the stuff of a time when there really were dead channels, and tuned-in heads bobbed to the tangible yet barely audible click that the phone made just before it rang. Different media have different dispositions, and I explain these in the hope of being descriptive, while mindful of any argument about the veracity of concepts of authenticity.

Jittering a bit and mumbling, Starker heads into a diner and has a seat at a booth. He orders coffee from a waitress we’ll meet again later while speaking in a hybrid of fake European accents. Making a mess while examining a ketchup bottle, then pouring a packet of artificial sweetener onto the table and snorting it up his nose like cocaine, he talks to himself as the surrounding patrons begin to grow nervous. One of them gets up, takes him by the shoulder and leads him outside. At one point the camera lingers for a moment—letting us know that a brightly colored fabric pouch that Starker has left behind means something.

As the film progresses, we watch Starker give the agents surveilling him the slip. After being knocked out and having his jacket tagged with a tracking device, he discovers the device, removes his jacket, and changes clothes to elude his pursuers. To illustrate the process of his being tracked we are treated to a primitive color representation of a 3D vector map of the city. It’s like an isomorphic video game built of an extruded and pastel colored De Stijl painting that says, “Welcome to the control society. Now you’re playing with power.” The whole sequence provides a taste of the ‘90s to come, bringing to mind critiques of the automatic production of space and tactical media projects like the Institute for Applied Autonomy’s iSee and the performances of the Surveillance Camera Players.

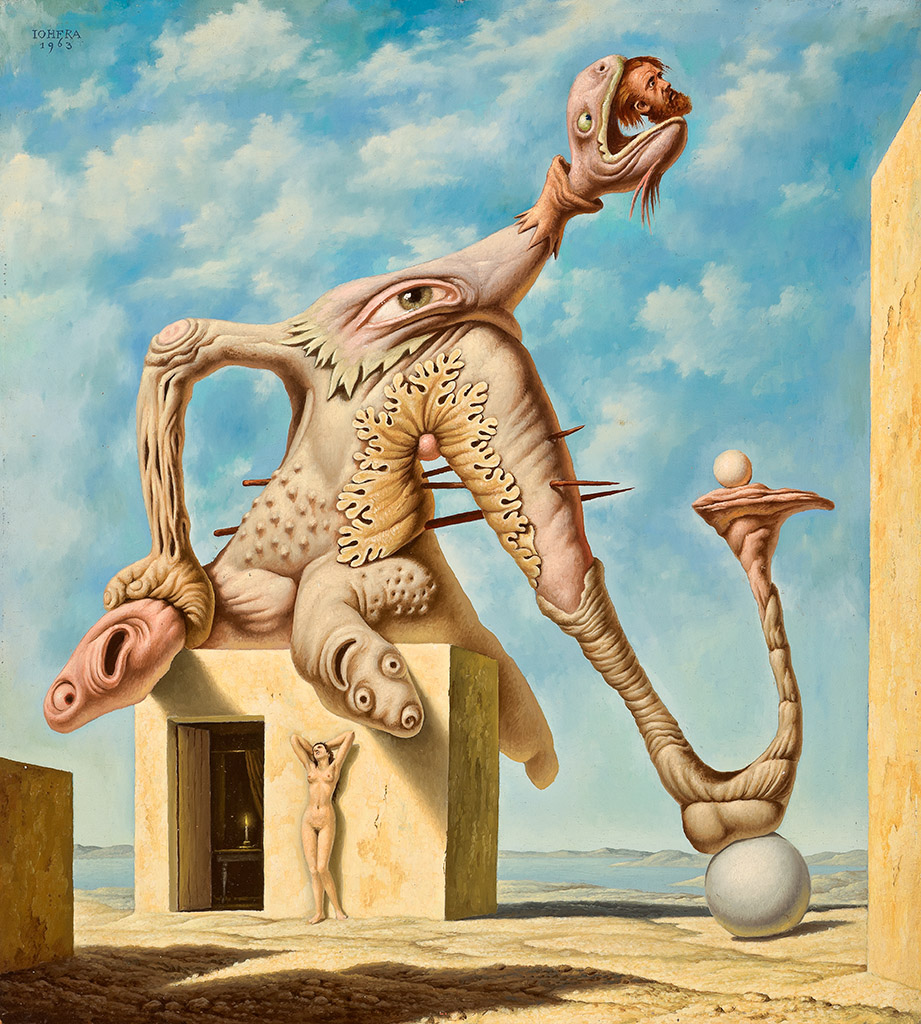

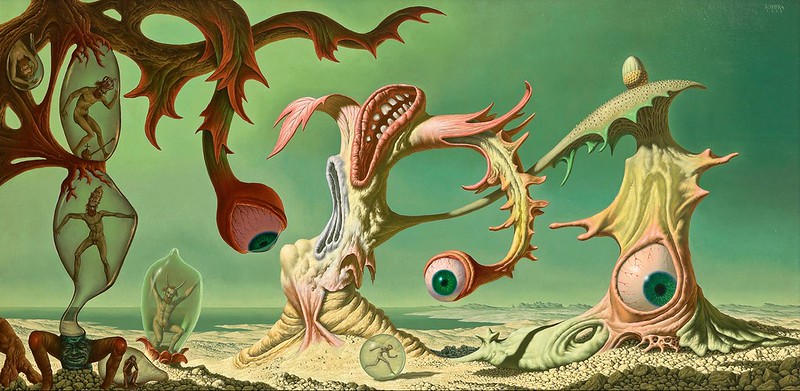

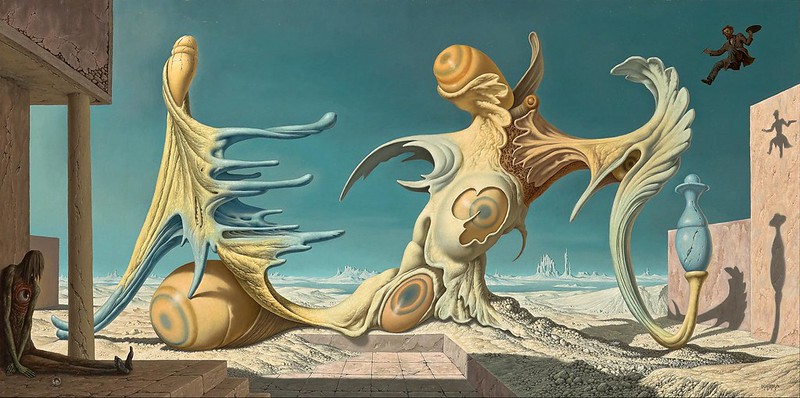

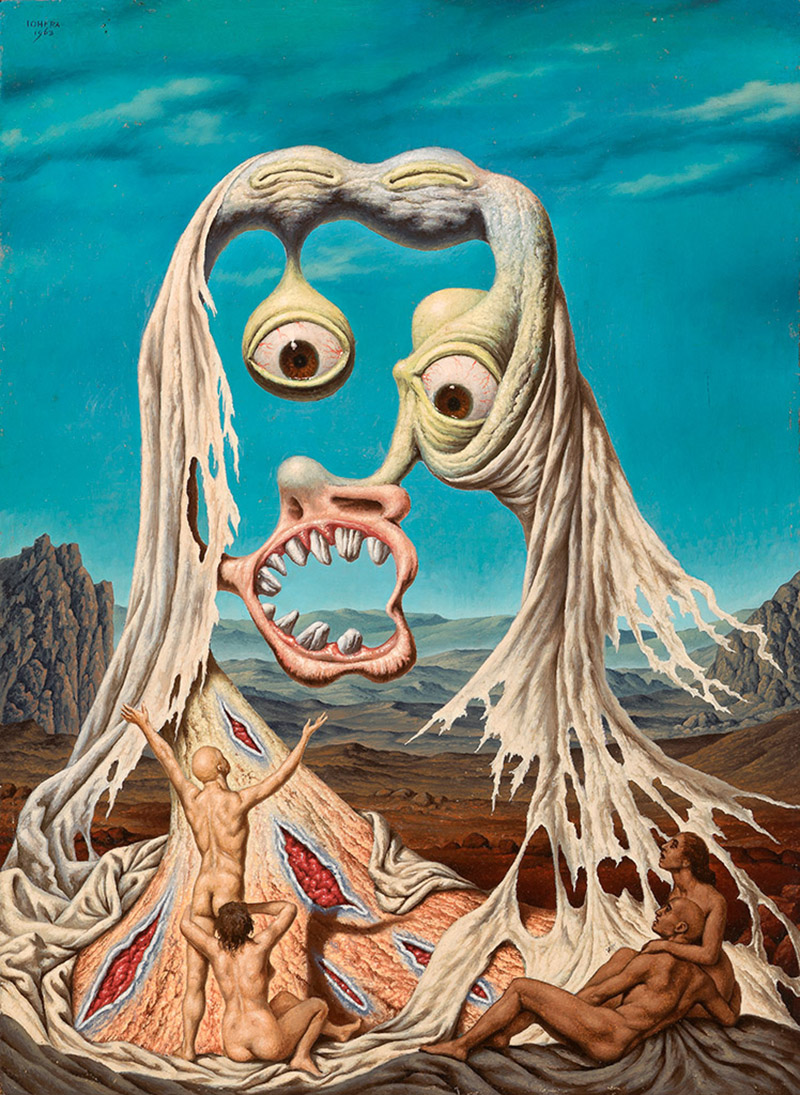

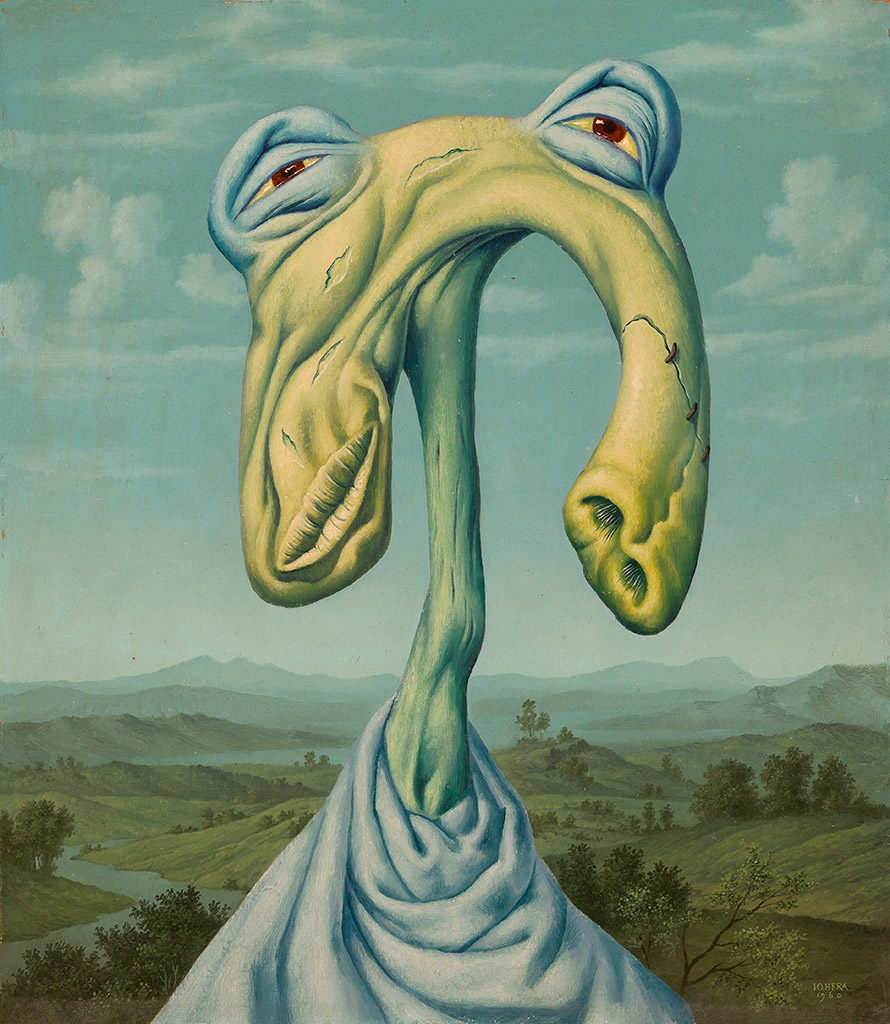

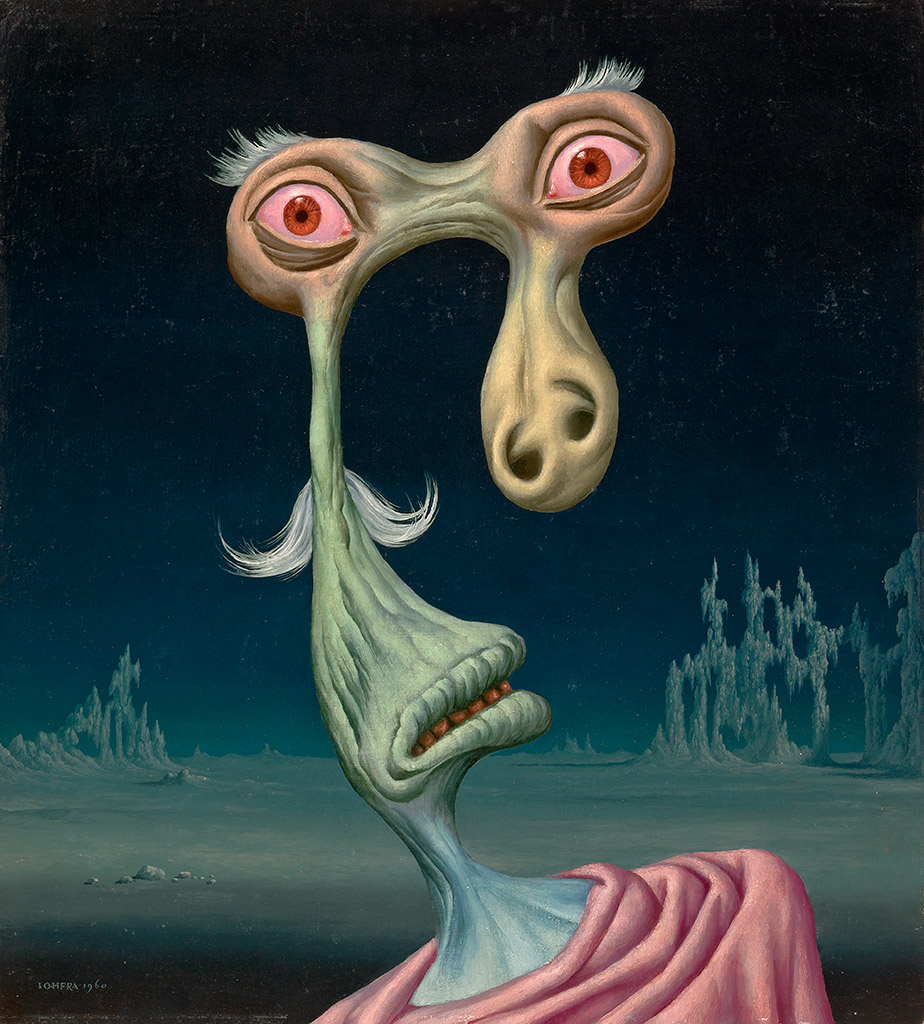

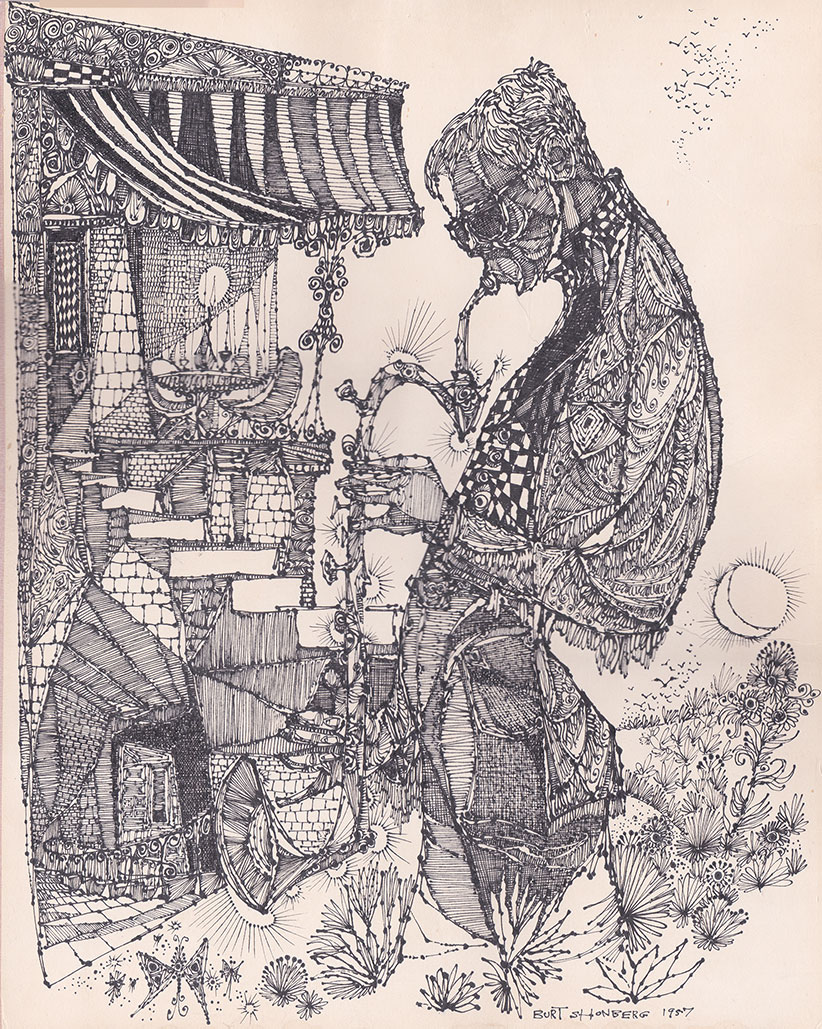

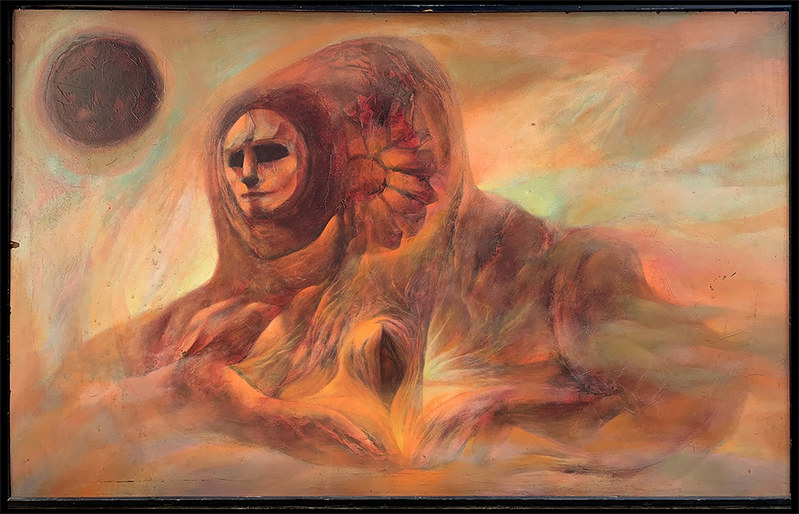

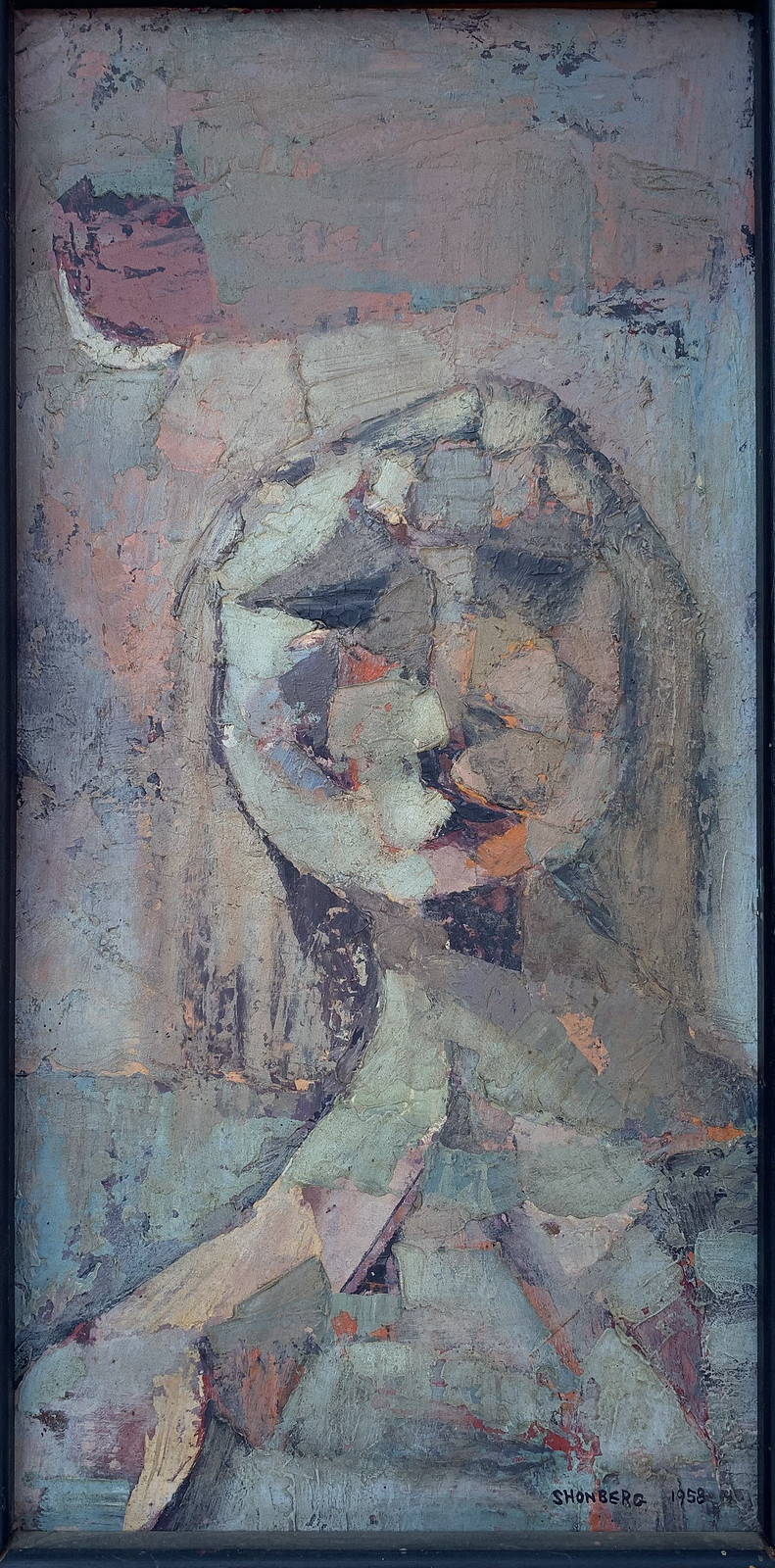

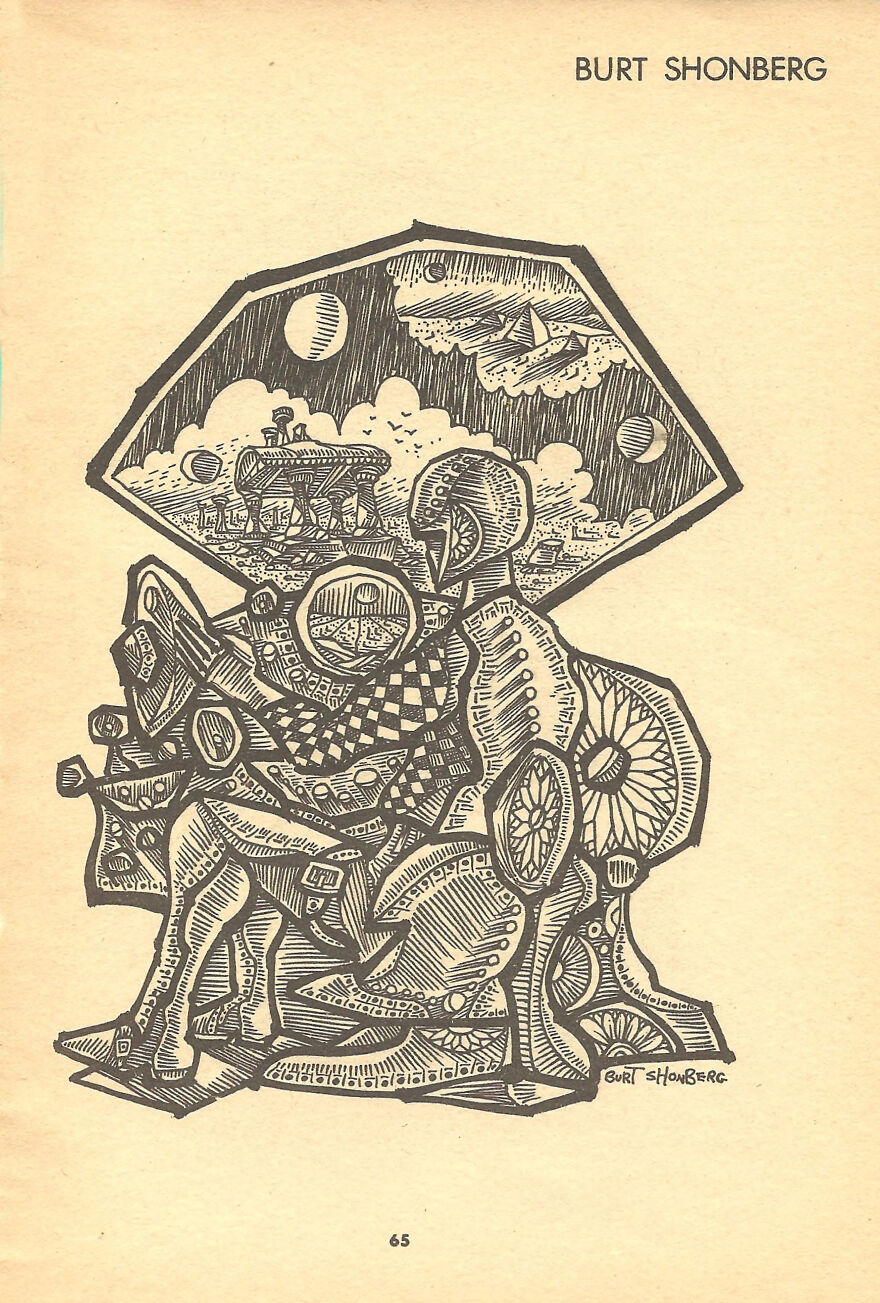

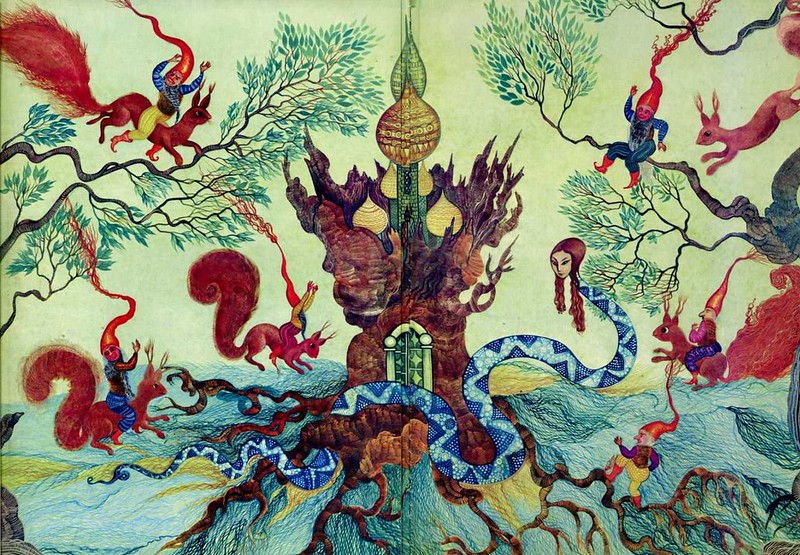

Starker retrieves the brightly colored fabric pouch from the trash outside the diner. He dons a new—and more ridiculous—disguise: a stick-on mustache and goatee paired with wire-rimmed glasses, a brown turtleneck, and a beige corduroy sports coat. Setting the scene for an art gallery opening, a lovingly blocked shot of Starker creates the sort of recursion we would associate with a Magritte or Escher through a row of champagne flutes. The camera lingers over a series of paintings reminiscent of Basil Wolverton’s or Erol Otus’s more psychedelic work. Gallery patrons talk trash about the paintings and each other while Starker shoves food in his pockets—John Belushi in Animal House style—as a lovely minimal synth piece by Robert Shaw, the director’s brother and creator of the computer generated effects seen through the film, begins to warble and flutter.

Conversing with the fictional creator of these paintings (in reality those of writer/director Chris Shaw himself), a flat-topped New Waver wearing a mustard yellow dinner jacket over a t-shirt, our ludicrously costumed hero mentions preparing to “wake people up.” As they discuss the artwork hanging on the gallery walls, they stop to look at a storyboard—which we realize is the storyboard of the current scene. As the artist begins to realize the same truth, he becomes enraged. He screams, but none of the patrons seem to notice or care.

The film meanders for a while, if it was not already meandering. We see the junior and senior agents discuss an analysis that reveals no discernible patterns in Starker’s behavior, and they escalate their attempts to find him. Now at the artist’s apartment after the art opening, Starker is coaxed into revealing his plan: “All we have to do is change the program!” he says, later addressing the painter’s skepticism with, “I have the way. The way is here—in my package!” Removing the pouch from an inside coat pocket, Starker then opens it to reveal a white plastic disc approximately the size of his hand. The artist remarks that it resembles a urinal deodorizer.

Starker goes on a tear: “Science is a jealous god.” The mystical “separates us from robots.” “What I am holding is a mutant biological organism.” He almost immediately contradicts himself and says the substance is just a placebo because people require a scientific reason to believe in something and that that is necessary for “the dream” to have power. He explains that he is going to dose the city’s water supply with this substance and then it will spread around the world as people excrete it through their urine. Sort of an Amanita muscaria re-trip meets infrastructural schwerpunkt: The MacGuffin is Elan Vital as urinal cake.

A few meaning-laden but plot-insignificant scenes later, Starker heads back to the diner. After a scuffle in which he startles Susan (the waitress we saw earlier) and she kicks him to the ground, he pressures her to let him hide out at her place. Reasonably viewing him as a crazy and potentially dangerous creep, she declines his offer. But, after following her to her car, he convinces her to relent by claiming that he used to be a veterinarian and that he may be able to explain the lethargy of the cat in a carrier in her back seat. The absurdity of this caged animal suddenly appearing to move the plot along is rendered even more absurd when Susan later explains that she already understood that the cat was lethargic because she had had it sterilized earlier in the day. There is something so metaphorically overt about this detail that I can’t tell if it’s a bad joke or a catastrophic mistake. In any event, Starker seems no less concerned about going home with a woman that left a post-op feline in the back of a car all day than Susan is about bringing home a man who claimed he was being followed and sat in her place of business snorting Sweet and Low through a straw while ranting in a fake French accent.

I will omit a lot of interpersonal awkwardness, strange dialogue, and things that may be significant to alternate interpretations in revealing that Starker crashes at Susan’s place (Pop Tarts and chill). The time they spend together only serves to make her subsequent death at the hands of the Starker’s pursuers insufficiently tragic to motivate his subsequent attempt at revenge. Discovering her murder at the hands of the Izod-clad archons, Starker—now in drag and blackface—follows the agents back to their bosses’ HQ. They enter through a large circular metal door, and Starker, who they don’t realize is following behind, is unable to enter.

Their boss, perhaps too obviously referred to as the “Agency Director” in a film about agency panic, laments his “monstrous” newly installed cybernetic arm. In an abrupt spasm of the plot that seems to indicate that the Director’s body is deteriorating, a lab-coated flunky soothes him by explaining that he has created that ultimate mad-scientist expression of mind-body dualism: a machine that can transfer a mind into another body. The camera cuts to Starker, unseen on the Agency Director’s CCTV, who is loading a pistol. He tries to find a way to open the door while the minions inside hurry to find a body to receive the Agency Director’s mind. The agents open the door and grab Starker, having seemingly no idea that they have apprehended the very person they were relentlessly pursuing earlier. Starker drops his gun in the struggle, and they strap him to a chair and lower a brain transfer apparatus over his head.

“Let me out! It worked!” Starker says, but it’s not clear if the process was successful or if Starker is trying to convince the agents that it was. We’re left to wonder if this Camp Concentration-style mind transfer worked at all. It’s set up as a techgnostic climax that never happens, as if this cyberpunk yacht rock anthem makes it to the guitar solo just as the amp blows. The enraged Agency Director yells and tells his minions to get rid of “her.” They throw Starker out, not seeming to care that this random person just entered their secret bunker, and still not realizing that it was Starker himself.

The final quarter of the film involves agents pursuing Starker while the Agency Director’s body is gradually replaced with a mechanical one. The music is great here and evokes both a sort of period instrumental soft rock call-center hold music and early Chrome. Someone with disposable income should release a proper soundtrack.

Now looking like a lo-fi Robocop or a reject from a Shinya Tsukamoto film, the Agency Director’s cybernetic augmentations (or too on-the-nose self-amputations) have endowed him with new powers. He accesses satellites while issuing abrasively vocoded directives that also appear on a camera-facing screen, perhaps to ensure intelligibility to the audience. Starker’s location is revealed on a map as crescendoing lo-bit sound effects accompany synth pads and drums. “Eradicate!” The Agency Director yells in a Davros-like moment. The camera cuts to Starker hopping over fences and traversing a roadside embankment, while the Agency Director seems to glitch out as he installs one last bionic eye into his head.

Now fully metal-skinned and ambulatory, he walks over to a pool of water inside headquarters. Elsewhere in a meadow, Starker stumbles into a pool himself, grabbing the white disc he revealed earlier. Somehow, both pools have become a sort of fold in space—the Agency Director reaches through and grabs Starker. They struggle, each remaining primarily in their own physical location while their arms bend through each others’ space. Starker breaks free and releases the chemical in the white disc. White dust floats in the air.

The end credits roll (well, melt, actually) and no further explanation is given.

***

Ultimately, outside of the beauty of the graphics and soundtrack, the joy and frustration of Split is that we are confronted with something that we can’t quite classify. Foregrounds and backgrounds of plot and image oscillate and change places, but so do the cues we’d typically use to determine whether or not we approached the material as comic or tragic, accidental or deliberate, high brow or trash stratum.

Watching Split (had I really seen it before?) left me with the distinct feeling that I just missed five minutes of it without leaving my seat. Shaw never really makes it clear what we should focus on, and the director’s commentary on the DVD doesn’t provide much help. There Shaw describes the film as “a dream that doesn’t really explain itself.” He does, however, talk a bit about chaos—not just disorder, but the branch of mathematics we might associate with Lorenz, Mandelbrot, the butterfly effect, and fractals. While history might provide examples of minor perturbations in complex systems causing them to collapse or toggle into alternate states, it seems here that chaos is really just used as a sort of “magic” (in the same way that “science” is used in superhero comics) to attempt to explain how Starker has a capacity for action that exceeds that of the archons that surveil him.

Really thinking about agency as contingent and distributed means something quite different and perhaps far more unsettling. I’d like to tell you that Split reveals a negotiation between ideas of cowboy individualism on one end, and on the other an appreciation of the behavior of complex adaptive systems of which human “individuals” are both composed of and parts of. In reality, the film presents 20th century ideas of autonomy and individuality taken to such an extreme that they become a bit goofy. The film presents an inverse relationship between attachment and individuality. Take, for example, this dialogue between the two primary agents who discover and begin tracking Starker, in which the frustrated junior agent asks:

How can he make it? We all have something: our family, our friends, something, but he… he gets by on nothing. How can he be that free? No human needs, no weaknesses, no feelings, nothing.

As they discuss their pending report to the Agency Director, the senior agent explains that they will just have to tell it like it is:

No recurrent behavior, no attachments, no soft spots: superman.

So, the superman, the “free” man, is the man who cares about no one and has no routine. Attachment to others is presented in the same way that an ascetic might present an attachment to material things, but also as a commodity that the system of surveillance capitalism depicted in the film exploits. In the world of Split, one can either be “free” and thus detached from social forces one can’t actually detach from, or part of some sort of winkingly self-aware Matrix.

Many of the characters, including Susan, the painter, some street crazies, and the pursuing agents, seem to have some awareness that by participating in society they are being had. It’s as if they are wearing the glasses from They Live (1988) but realize that if they call attention to their alien overlords they will just be ignored anyway.

Shaw’s broader argument seems to be that as an “individual” who is truly “free,” Starker exists without a data-body; he’s an Übermensch who cannot be profiled or reduced to his so-called statistical self. As such, Starker stands outside of culture—the infrastructure of shared social and material substrates that both the one and the many call upon to act. But he still has the magic urinal cake, the fulcrum and lever by which he is super empowered.

Like a bad haircut, dosing the water supply with mutagenic hallucinogens seems cool in high school, when we are naive enough to dream that control is simply a matter of centralization and that shocking the dupes out of their somnambulism is something they will high five us for afterwards. But while portrayed as some sort of systems-disrupting black swan herald of a “new age,” maybe Starker—and the film itself—just represents a dance around the collapse of any sort of shared systems of meaning. After all, at the climactic moment when Starker releases the mutagen, the end credits roll. Were not shown what comes next—just the end of the now.

Jonathan Lukens is a cultural worker from Atlanta. His work has been shown at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, played through omnifarious speakers, and published in The Atlantic, Design Issues, and The International Journal of Design in Society.

Jonathan Lukens is a cultural worker from Atlanta. His work has been shown at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, played through omnifarious speakers, and published in The Atlantic, Design Issues, and The International Journal of Design in Society.

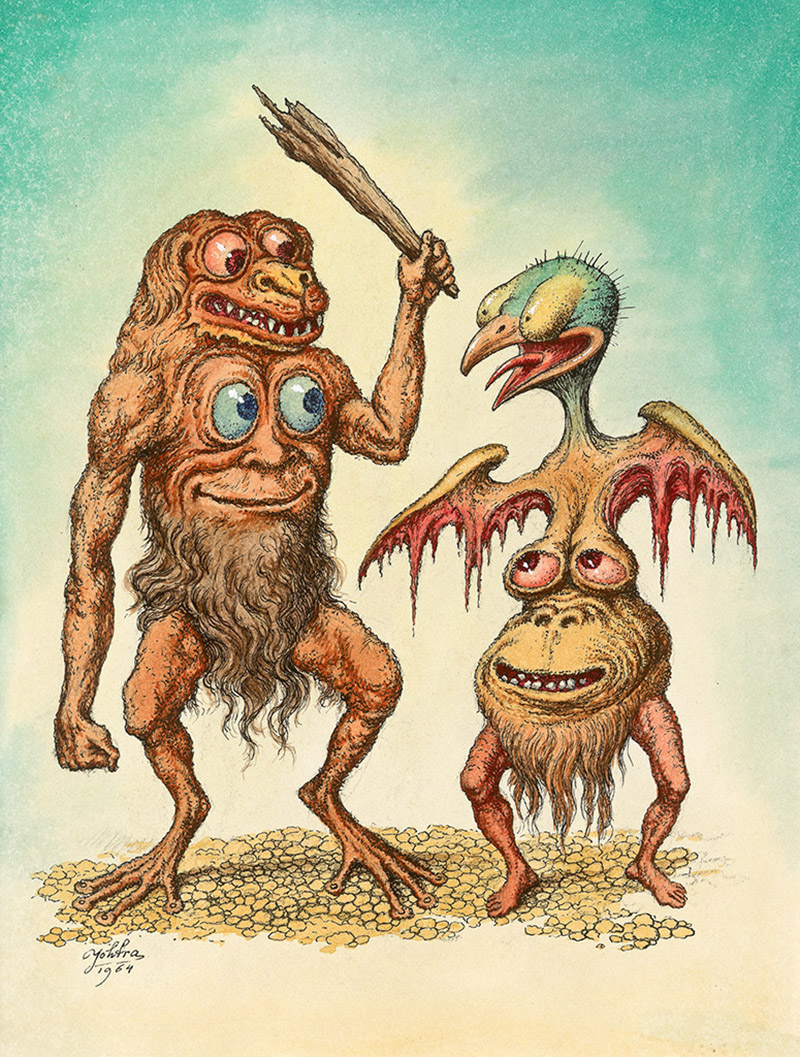

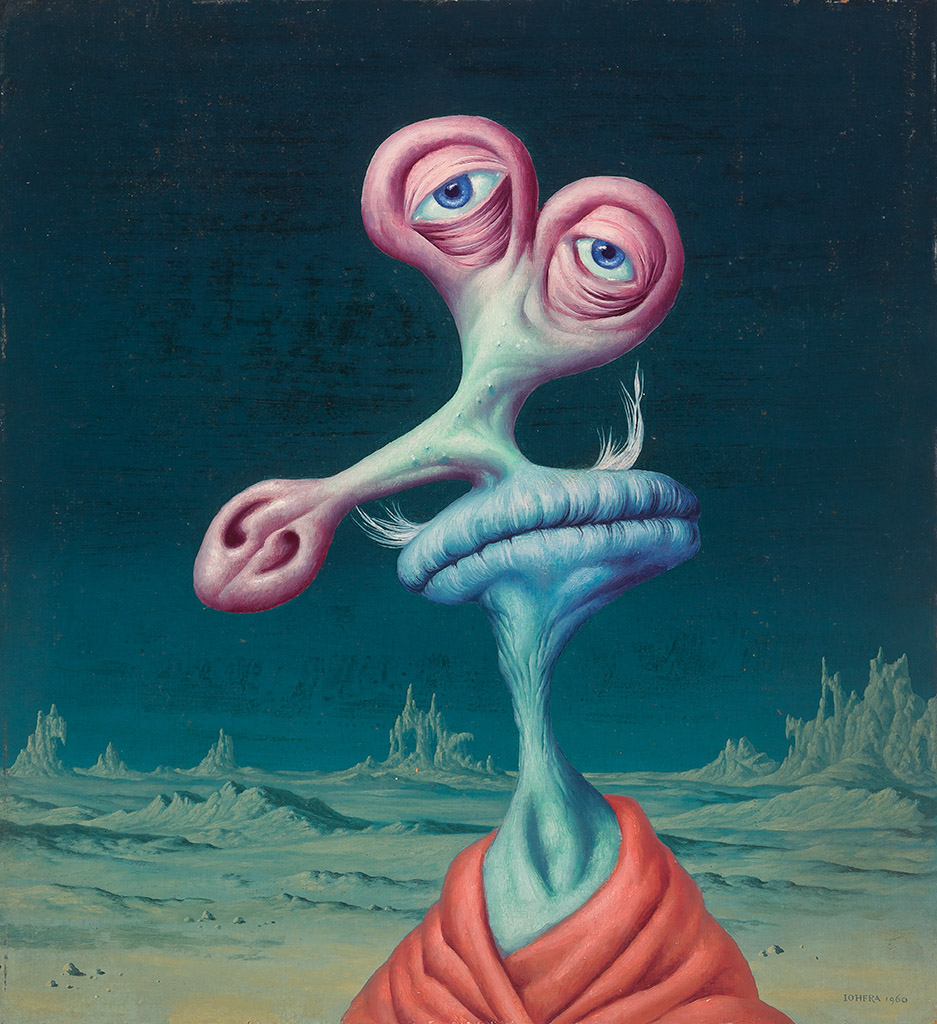

The Battle Between Good and Evil

The Battle Between Good and Evil  Ellen in Wonderland 3 - The visit to the forest with the human worms

Ellen in Wonderland 3 - The visit to the forest with the human worms  Ellen in Wonderland 2 - Ellen in dispute with a little harlequin

Ellen in Wonderland 2 - Ellen in dispute with a little harlequin  The Bummer - Odysseus at Kirke

The Bummer - Odysseus at Kirke  I made the impossible come true

I made the impossible come true  What do you think about marriage?

What do you think about marriage?  Study for - The Liberation of Andromeda

Study for - The Liberation of Andromeda  A Painful Encounter Artworks found at

A Painful Encounter Artworks found at