Jules-Descartes Férat - Illustration for Edgar Allan Poe's "The Pit and the Pendulum," 1884

- source

- source Original Roleplaying Concepts

- source

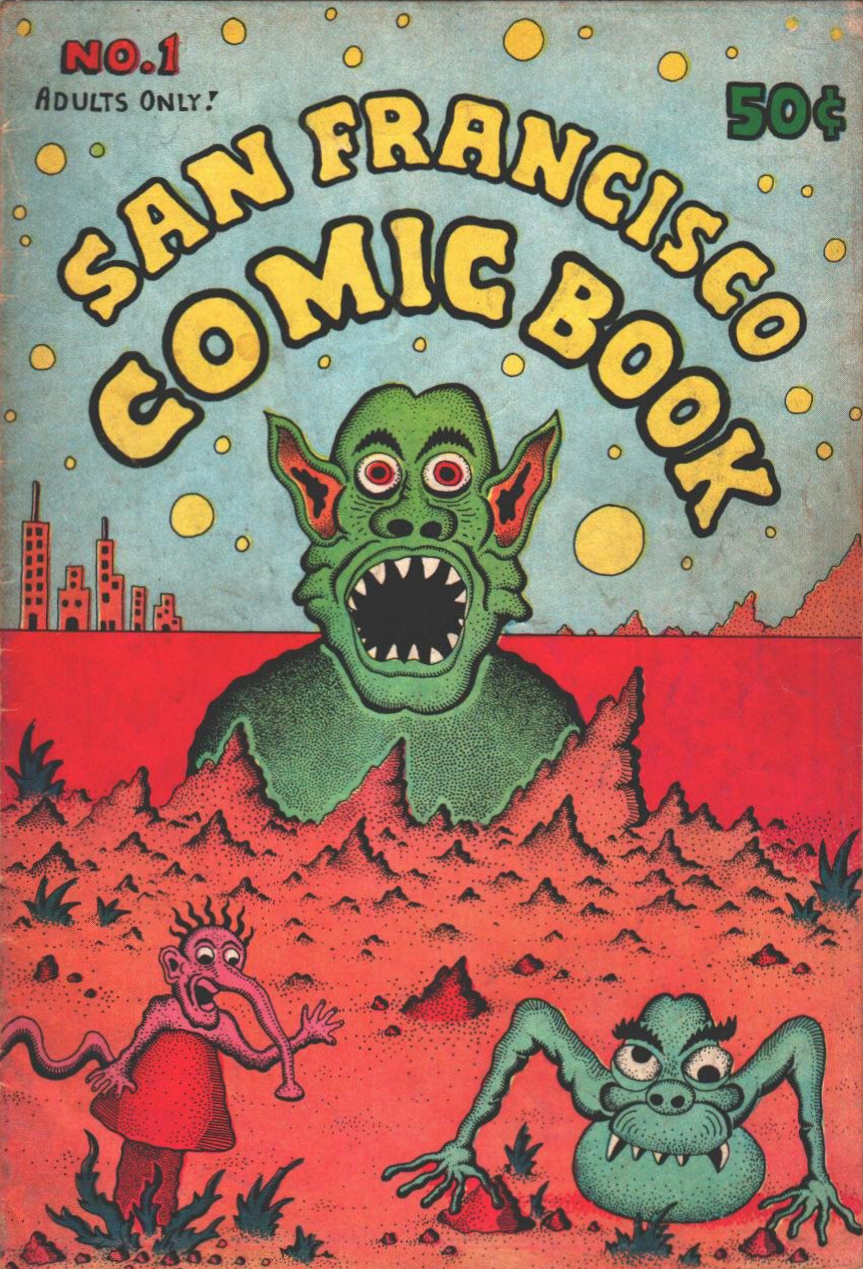

- source  San Francisco Comic Book, front - No.1, 1970

San Francisco Comic Book, front - No.1, 1970

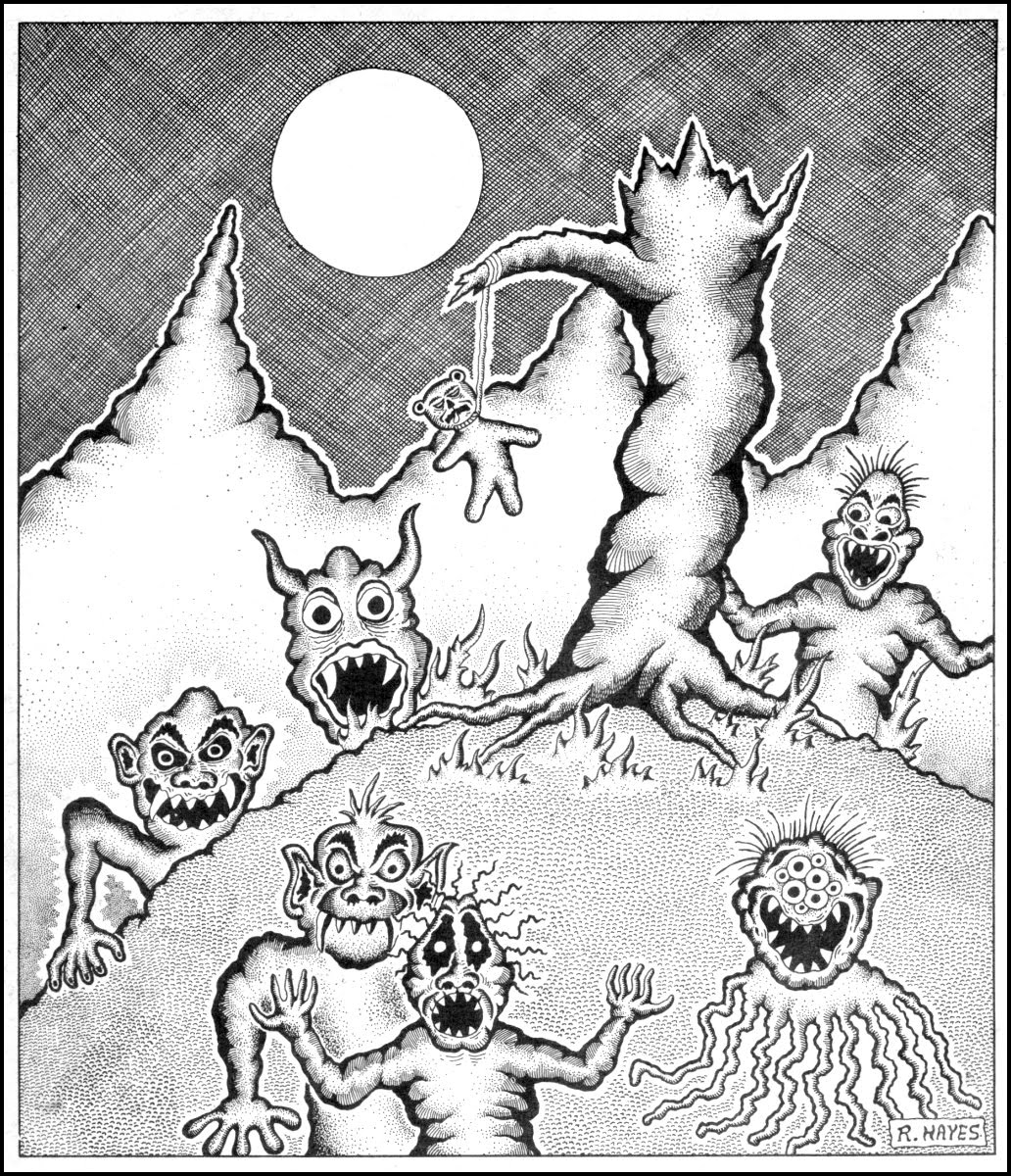

San Francisco Comic Book, back - No.1, 1970

San Francisco Comic Book, back - No.1, 1970

Invitation to Death, Bogeyman Issue 3, 1970

Invitation to Death, Bogeyman Issue 3, 1970

Art from Bogeyman Issue 3, 1970

Art from Bogeyman Issue 3, 1970

Untitled

Untitled  Interior Art From Bogeyman #3, 1970

Interior Art From Bogeyman #3, 1970

Stairway to Spiritual Awakening

Stairway to Spiritual Awakening

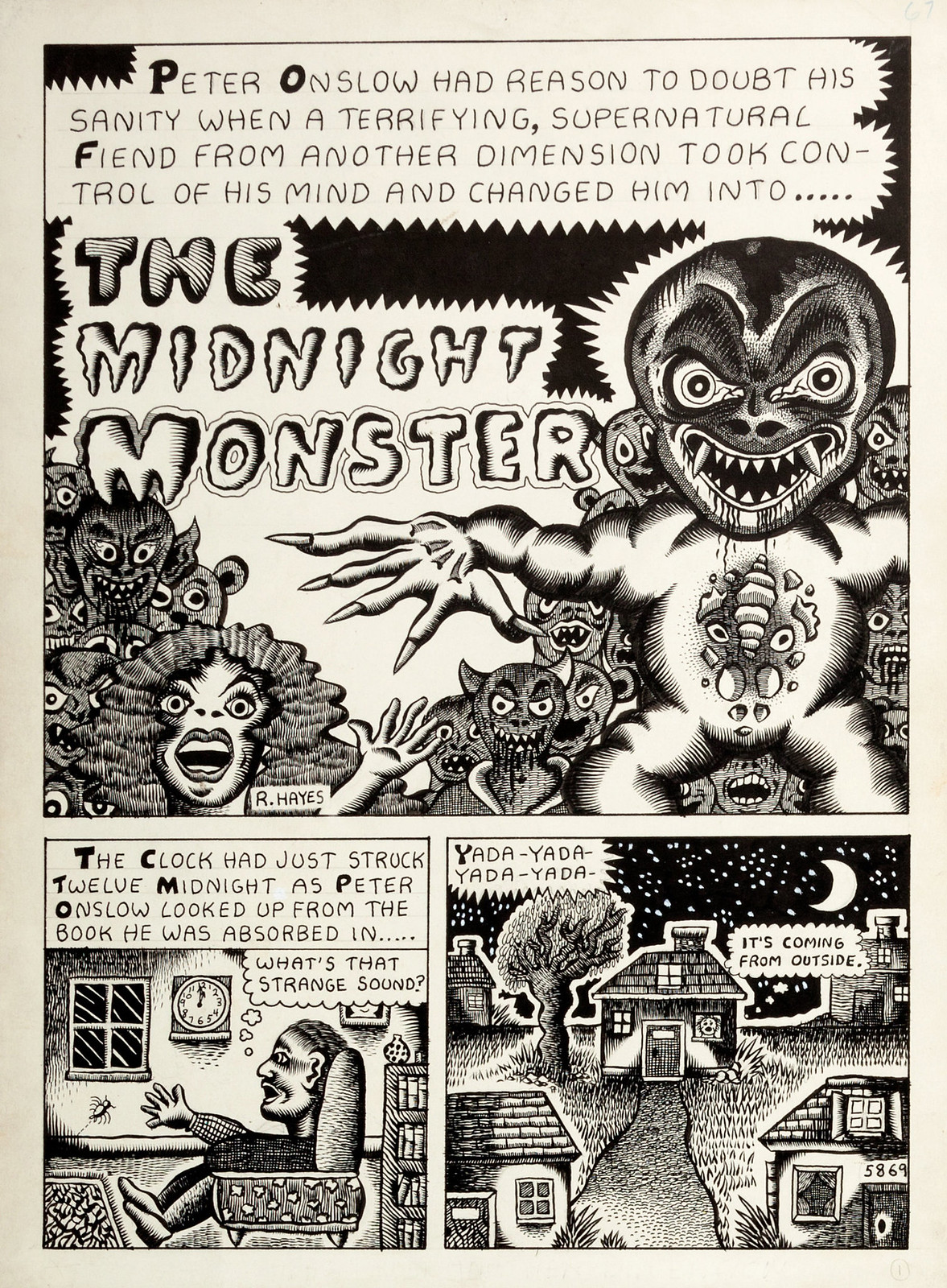

Insect Fear #3 "The Midnight Monster" Page 1

Insect Fear #3 "The Midnight Monster" Page 1

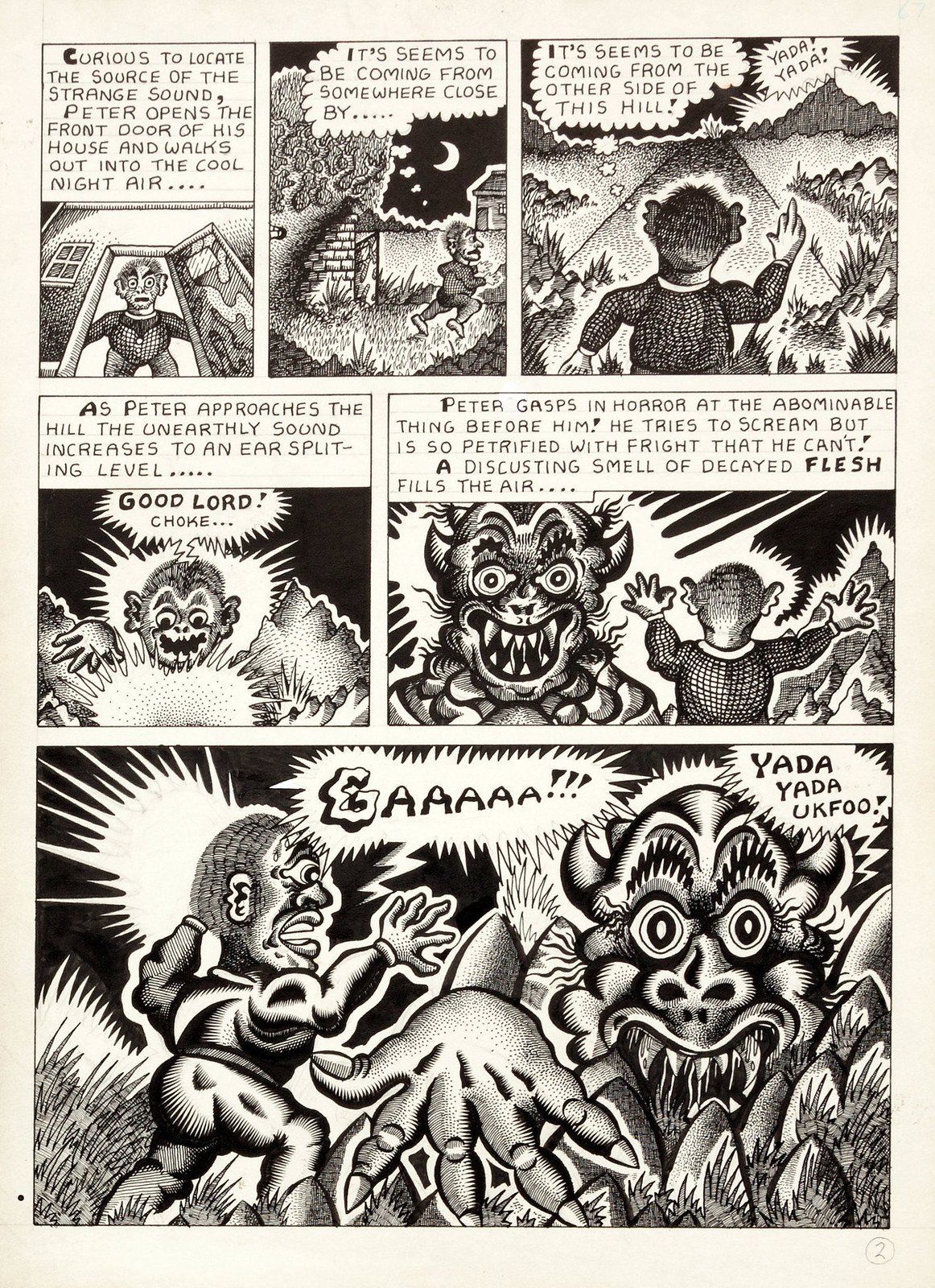

Insect Fear #3 "The Midnight Monster" Page 2

Insect Fear #3 "The Midnight Monster" Page 2

Insect Fear #3 "The Midnight Monster" Page 3

Insect Fear #3 "The Midnight Monster" Page 3

Insect Fear #3 "The Midnight Monster" Page 4

Insect Fear #3 "The Midnight Monster" Page 4

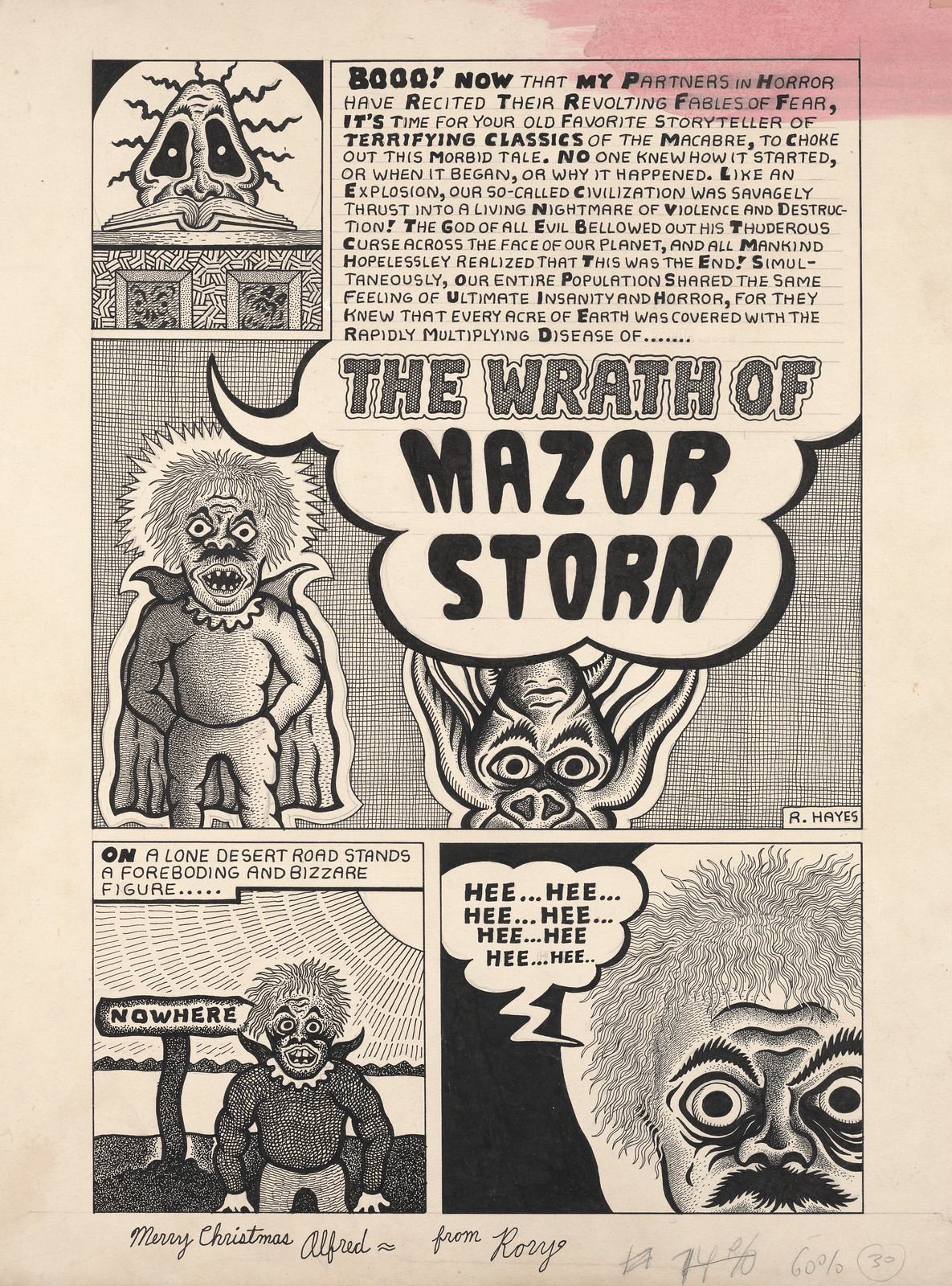

The Wrath of Mazor Storn, 1971

The Wrath of Mazor Storn, 1971

Major Storm, Insect Fear no.1 (page 1) 1970's

Major Storm, Insect Fear no.1 (page 1) 1970's

Major Storm, Insect Fear no.1 (page 2) 1970's

Major Storm, Insect Fear no.1 (page 2) 1970's

"Rory Hayes was one of the artists in the underground comix scene of America in the early 1970s. A protégé of Robert Crumb, he contributed to various underground comix magazines, such as Arcade, Bijou Funnies, Insect Fear, Snatch, Cunt Comics, Hydrogen Bomb and Skull.

Fascinated by horror since an early age, he published his own comic 'Bogeyman' in 1968. Hayes made a contribution to the comic book 'Queen of Hairy Flies', to which other underground artists like Spain Rodriguez, Brad W. Foster, Michael Roden, Ed Dorn, S. Clay Wilson, Bill Shut and others also made contributions. The book claimed to be a loose interpretation of an 18th century occultism book.An avid experimenter with drugs, Rory Hayes died in his sleep from an overdose on August 29, 1983, only 34 years old. " - quote source

Rory Hayes was previously shared on Monster Brains back on Halloween day of 2006.

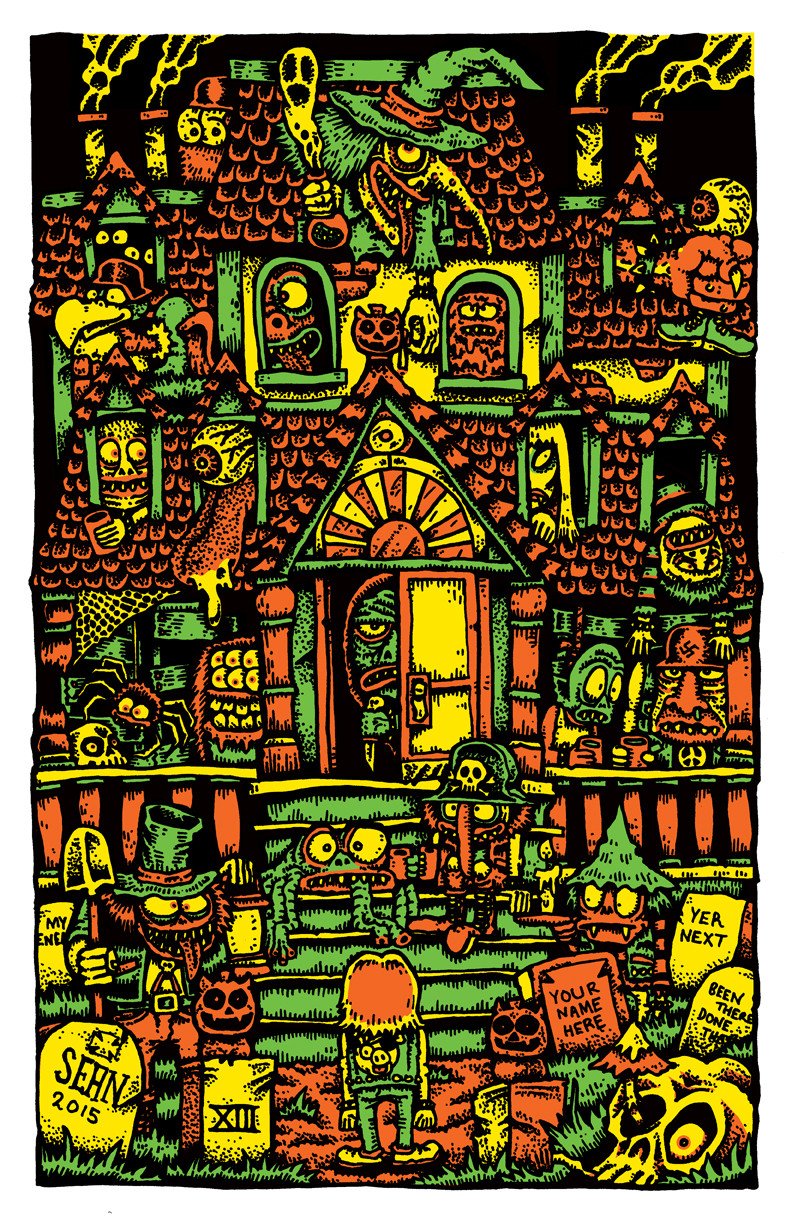

My friend Sean is running a kickstarter to fund a Halloween themed book full of his fantastic Halloween artwork, check it out!

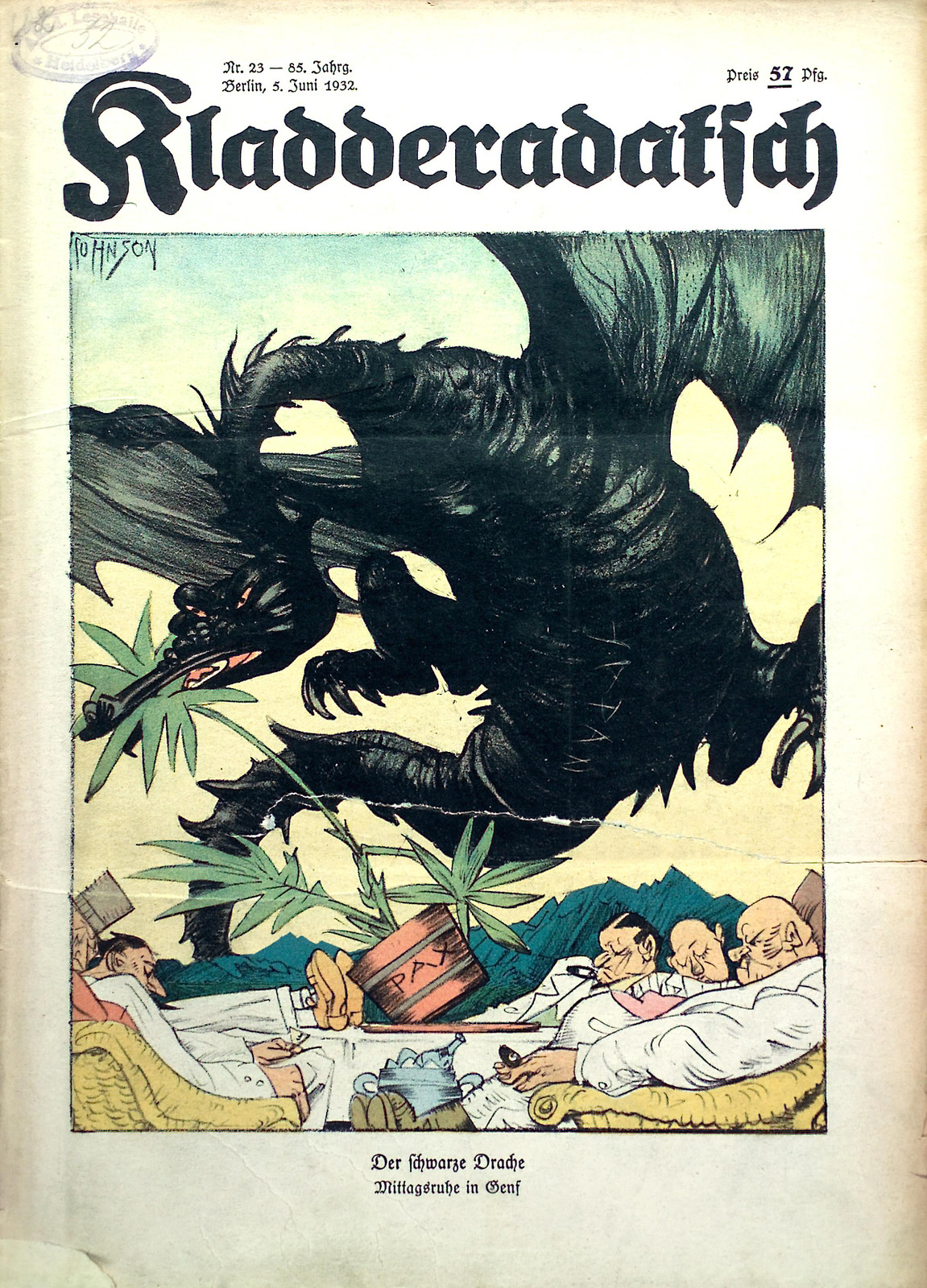

My friend Sean is running a kickstarter to fund a Halloween themed book full of his fantastic Halloween artwork, check it out!  Cover art by Arthur Johnson, June 1932

Cover art by Arthur Johnson, June 1932

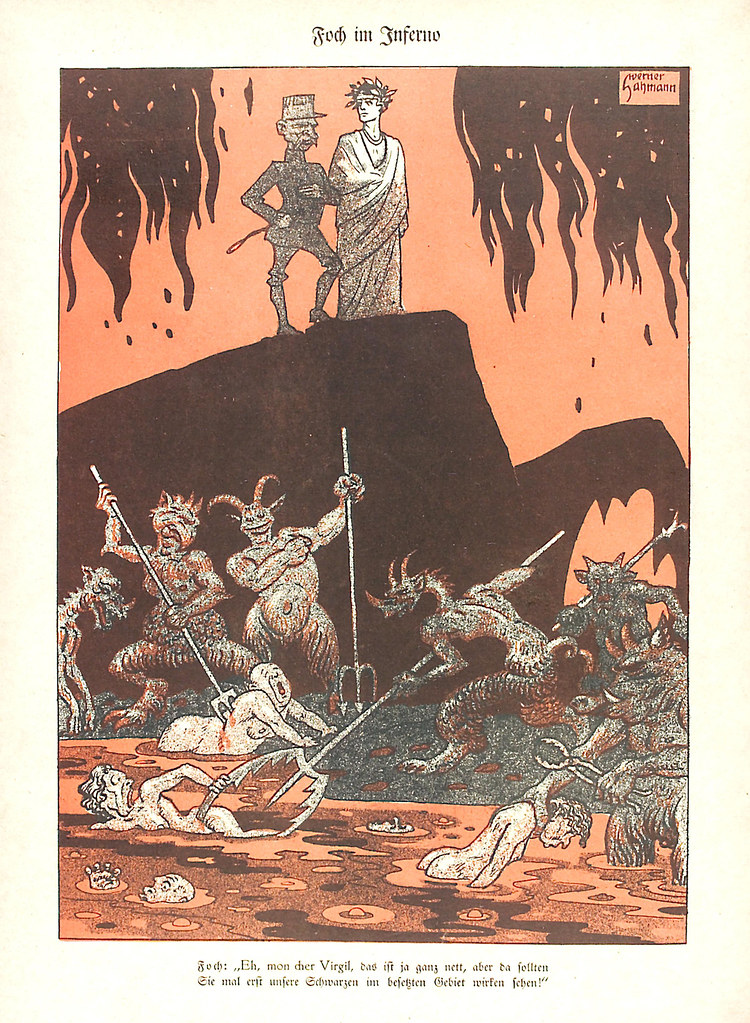

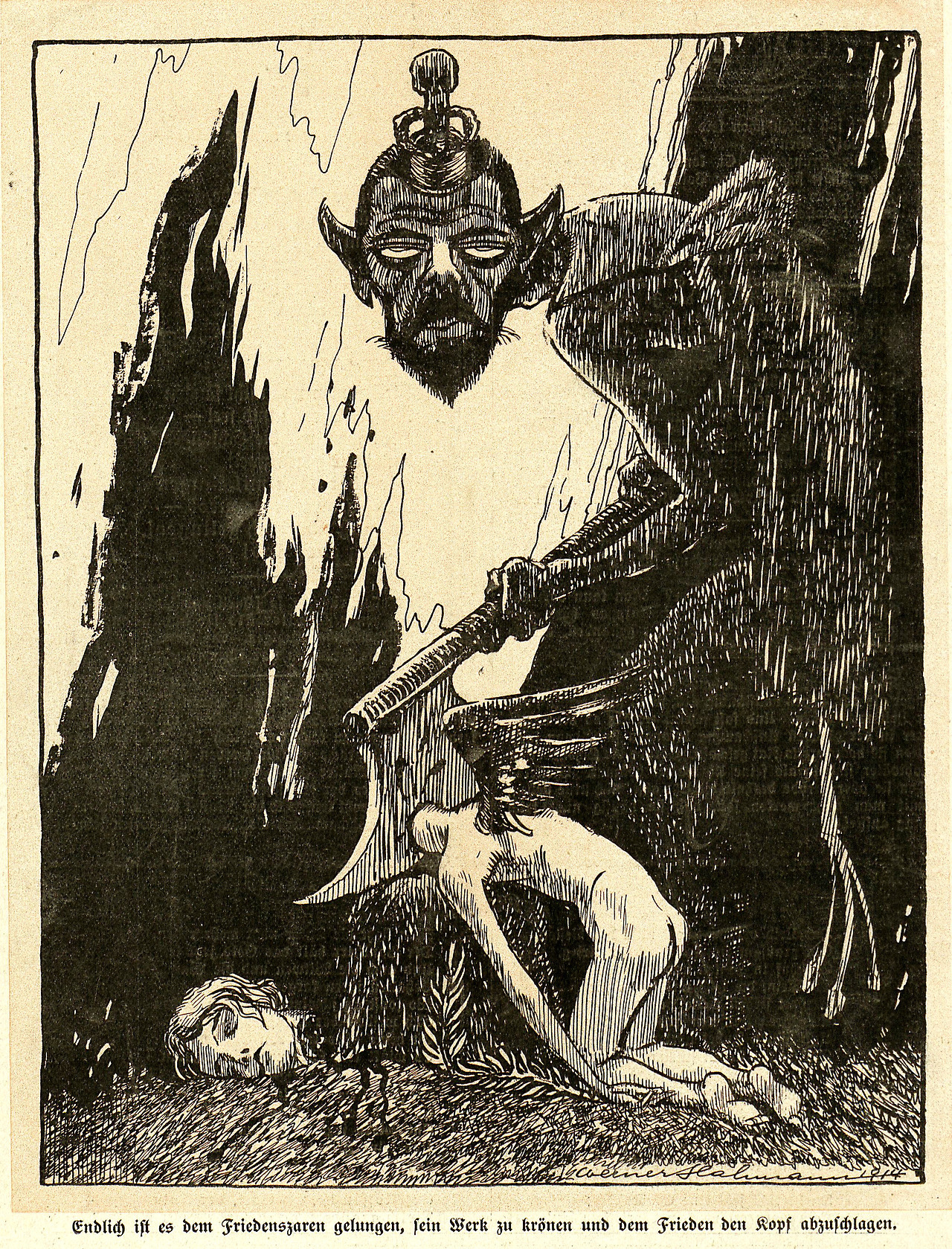

Interior art by Werner Sahmann, 1922

Interior art by Werner Sahmann, 1922

Interior art by Oskar Garvens, August 1937

Interior art by Oskar Garvens, August 1937

Interior art by Werner Sahmann, 1921

Interior art by Werner Sahmann, 1921

Cover art by Arthur Johnson, September 1931

Cover art by Arthur Johnson, September 1931

Interior art by Arthur Johnson

Interior art by Arthur Johnson

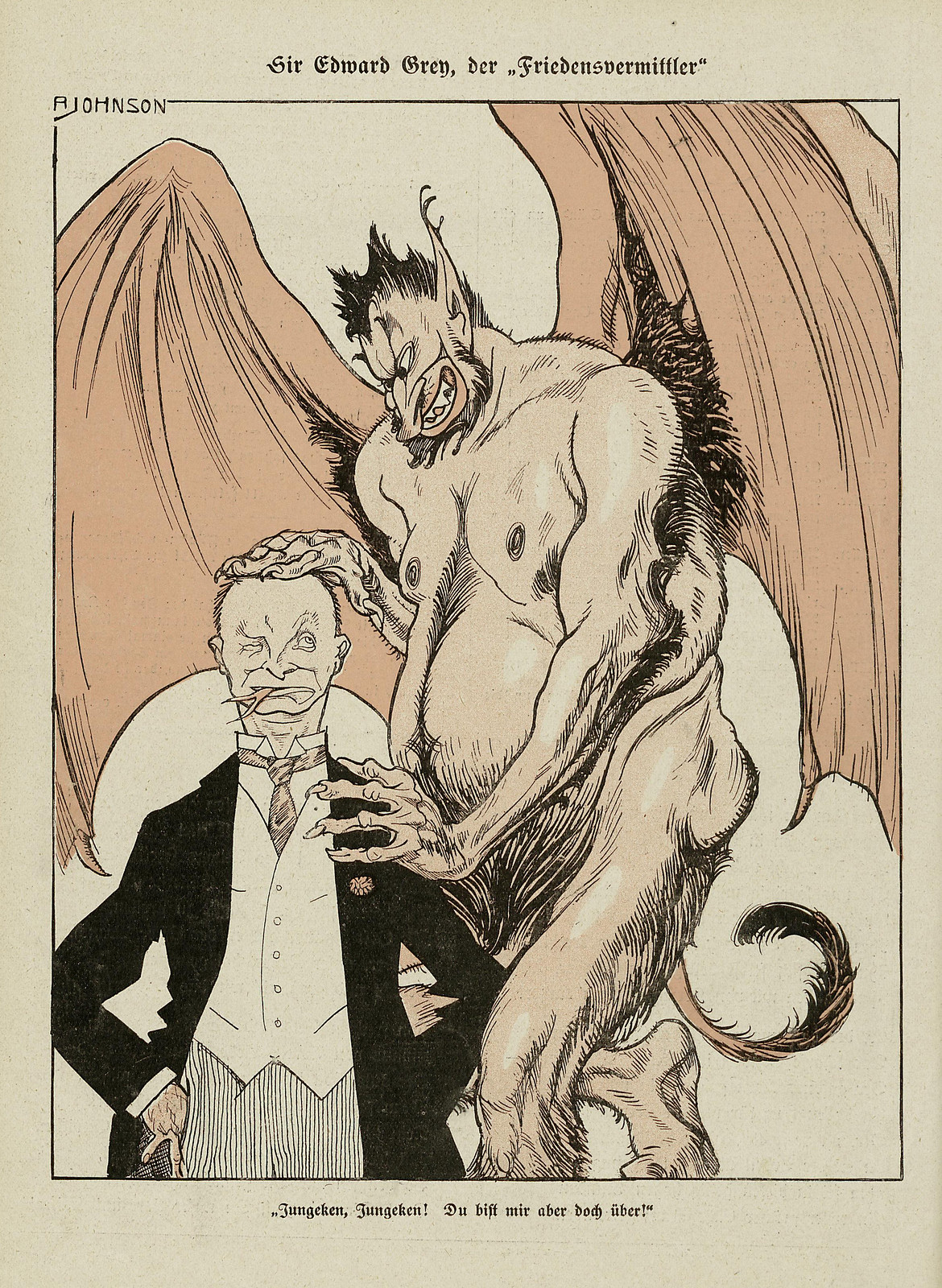

Interior art by Arthur Johnson, 1914

Interior art by Arthur Johnson, 1914

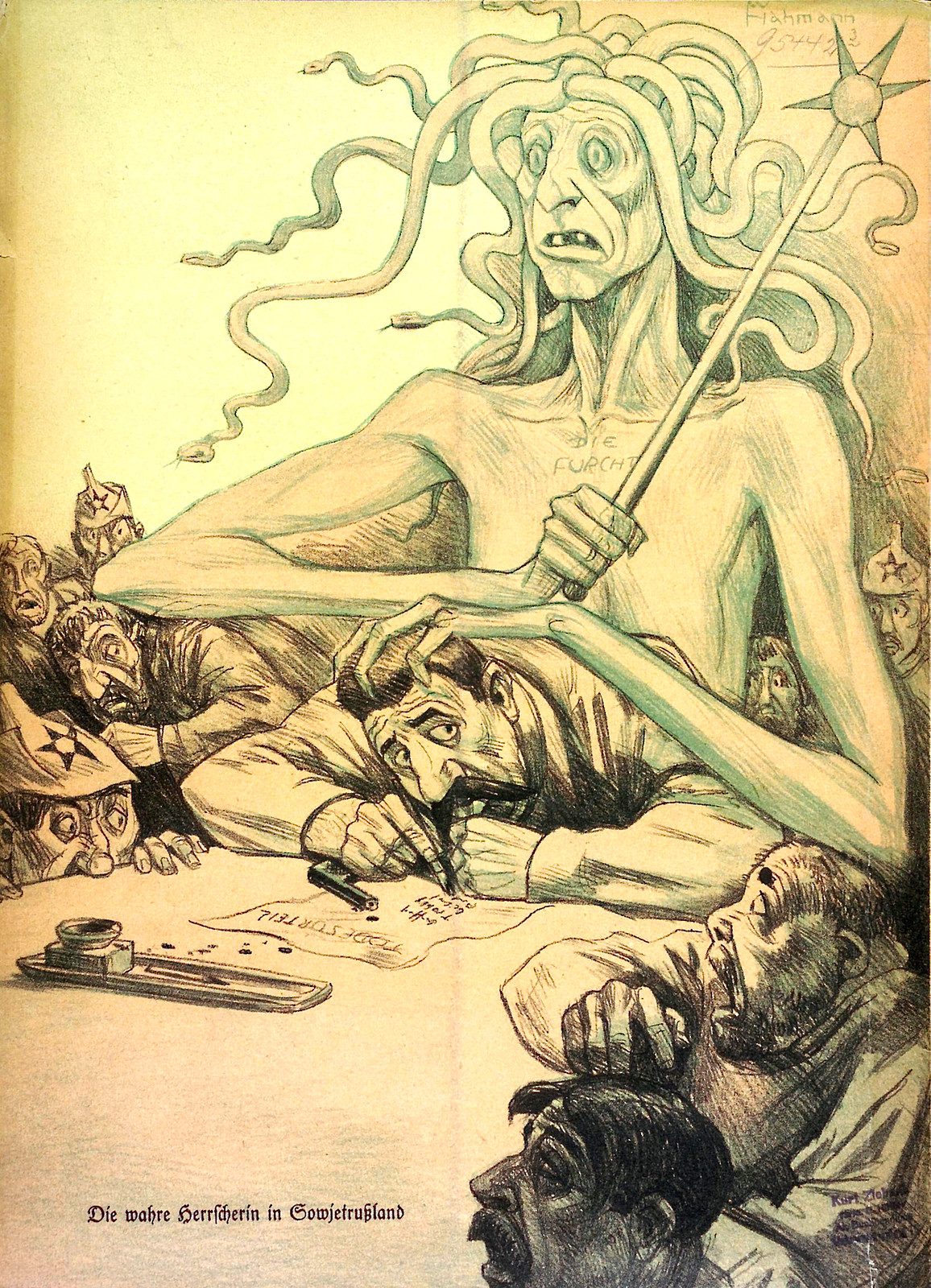

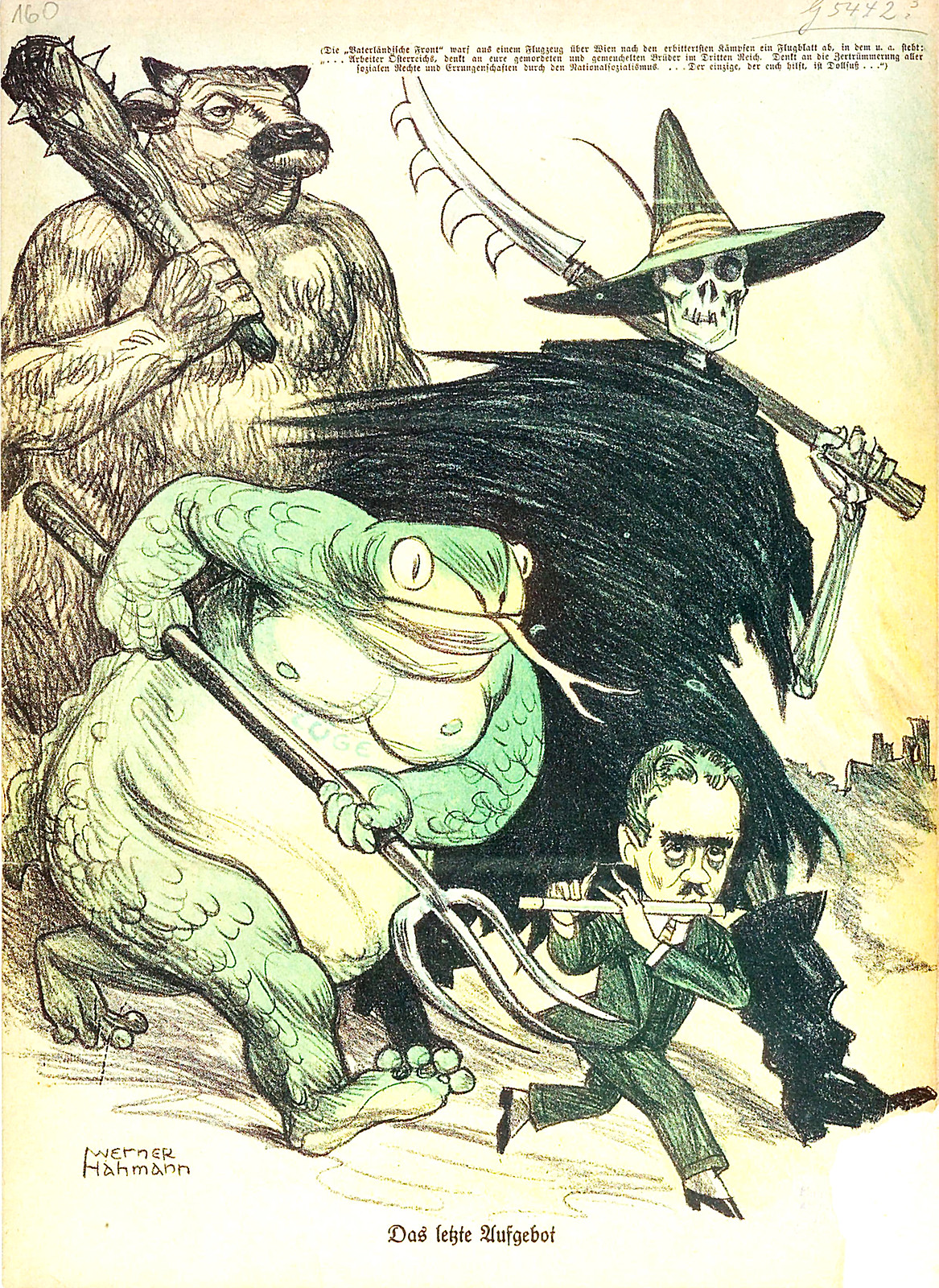

Interior art by Werner Hahmann, 1938

Interior art by Werner Hahmann, 1938

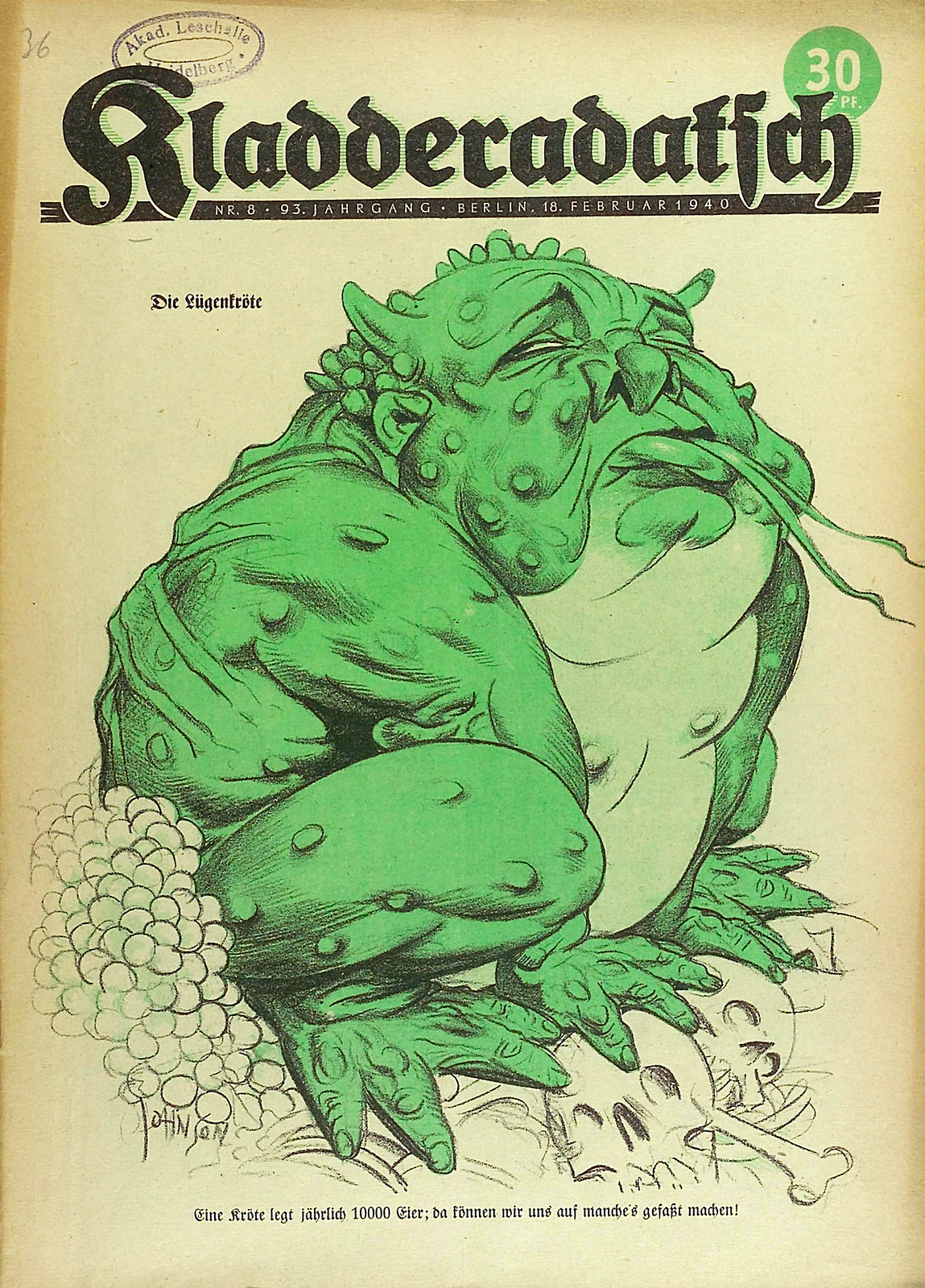

Cover art by Arthur Johnson, February 1940

Cover art by Arthur Johnson, February 1940

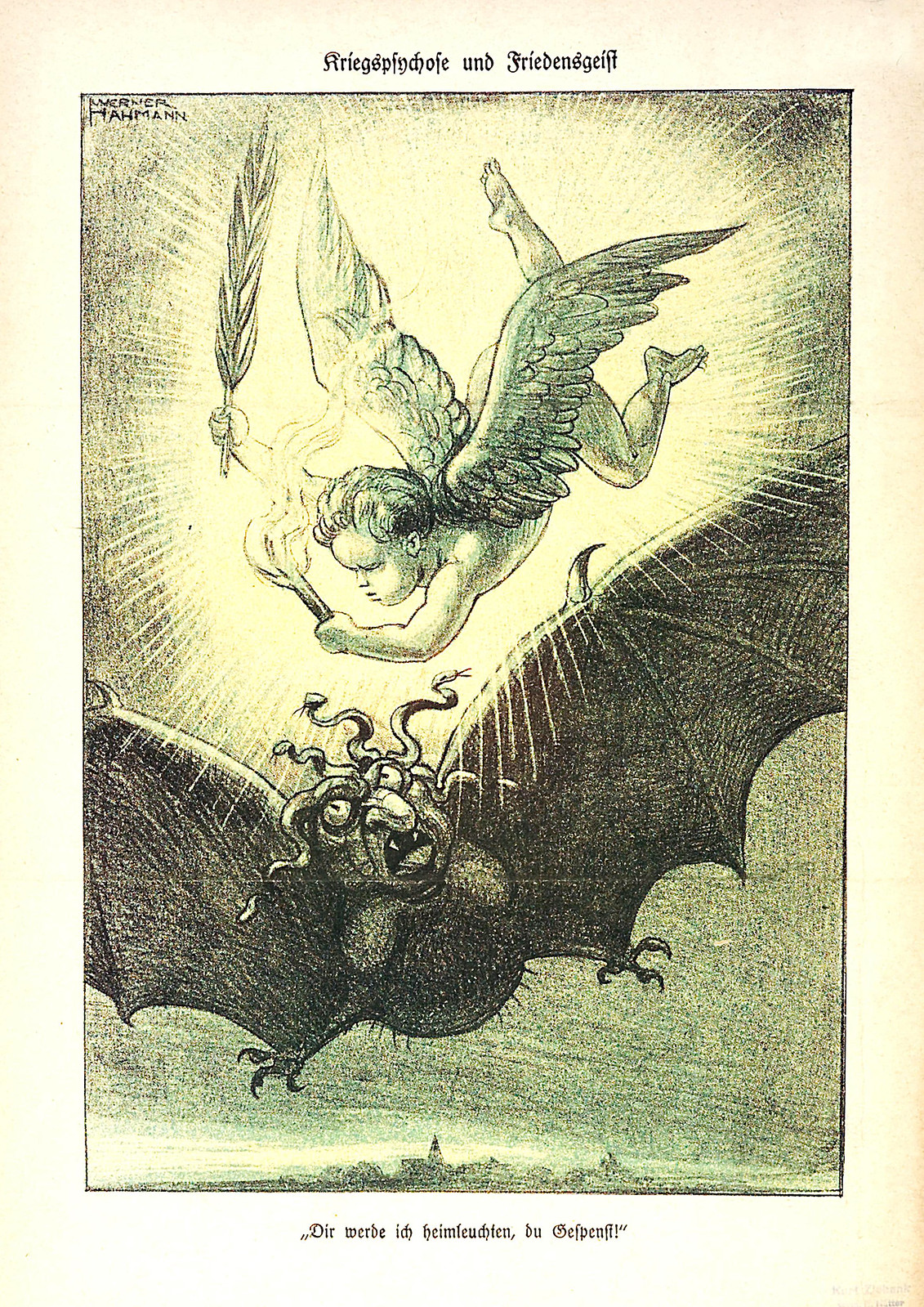

Interior art by Werner Hahmann, 1940

Interior art by Werner Hahmann, 1940

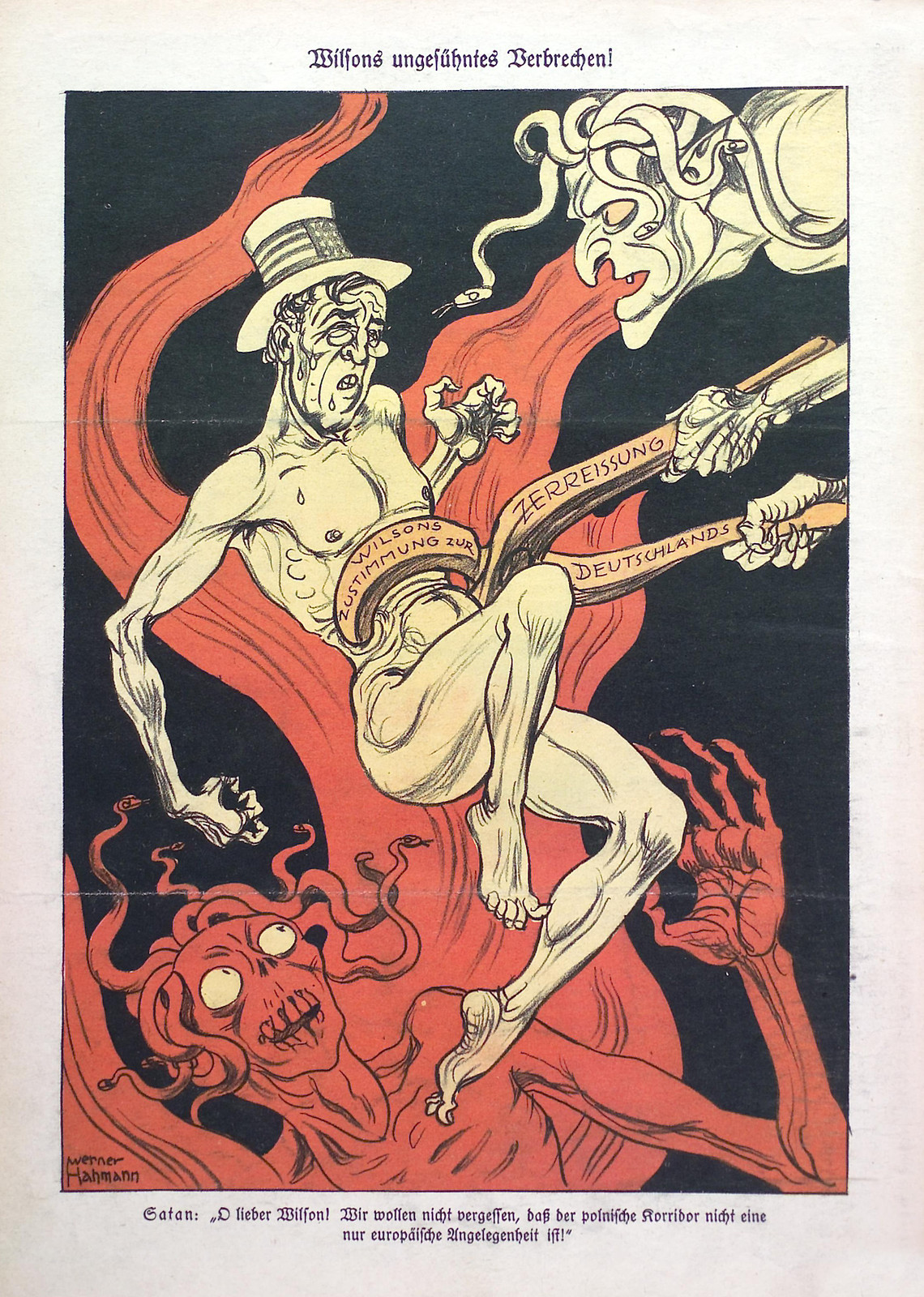

Interior art by Werner Hahmann, 1931

Interior art by Werner Hahmann, 1931

Interior art by Werner Sahmann, 1921

Interior art by Werner Sahmann, 1921

Interior art by Werner Hahmann, 1921

Interior art by Werner Hahmann, 1921

Cover art by Oskar Garvens, January 1931

Cover art by Oskar Garvens, January 1931

Interior art by Werner Sahmann, 1922

Interior art by Werner Sahmann, 1922

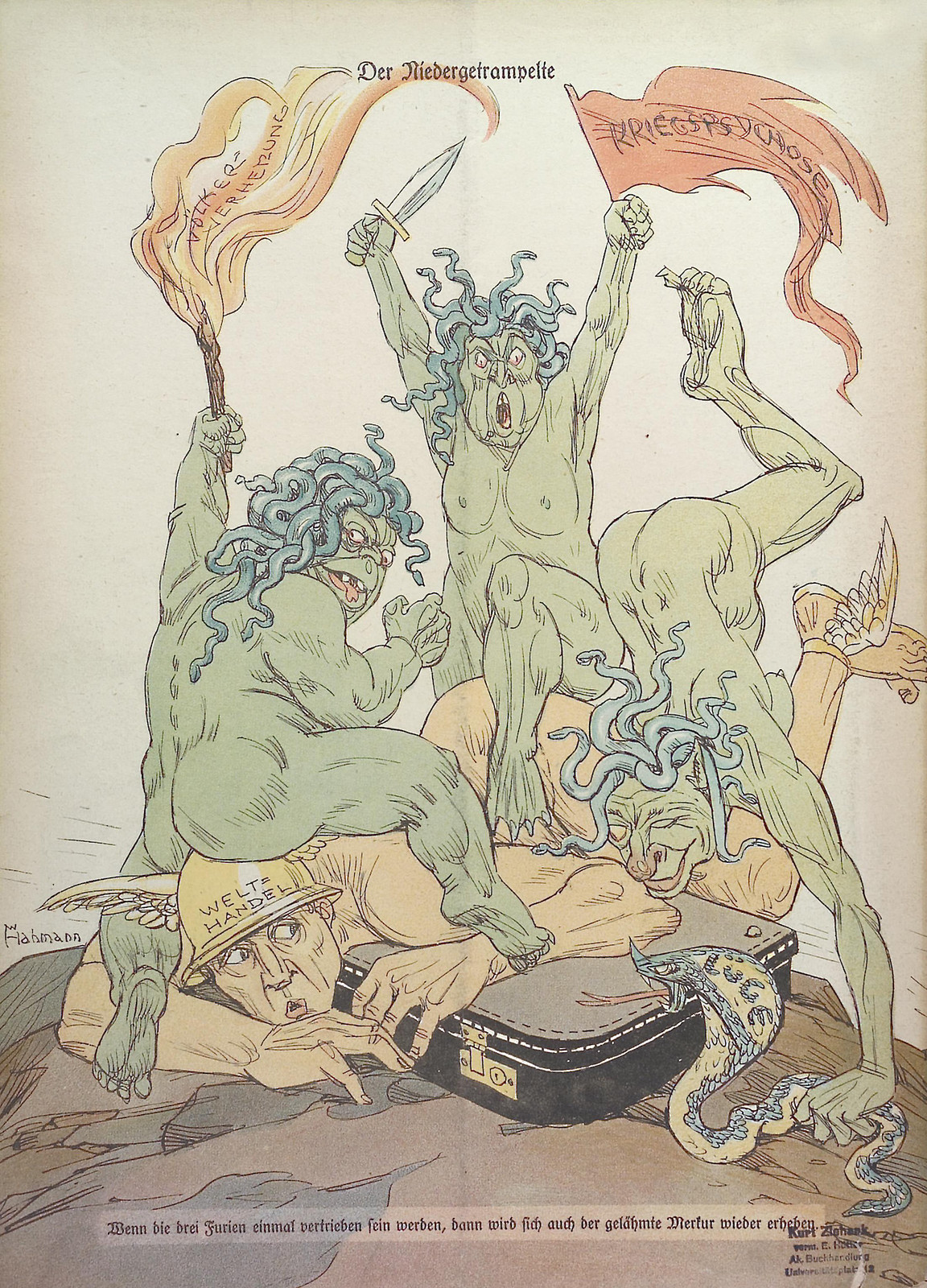

Interior art by Werner Hahmann, August, 1914

Interior art by Werner Hahmann, August, 1914

Interior art by Werner Hahmann, 1938

Interior art by Werner Hahmann, 1938

Interior art by Werner Hahmann, 1936

Interior art by Werner Hahmann, 1936

Cover art by Arthur Johnson, 1923

Cover art by Arthur Johnson, 1923

Interior art by Werner Hahmann, 1931

Interior art by Werner Hahmann, 1931

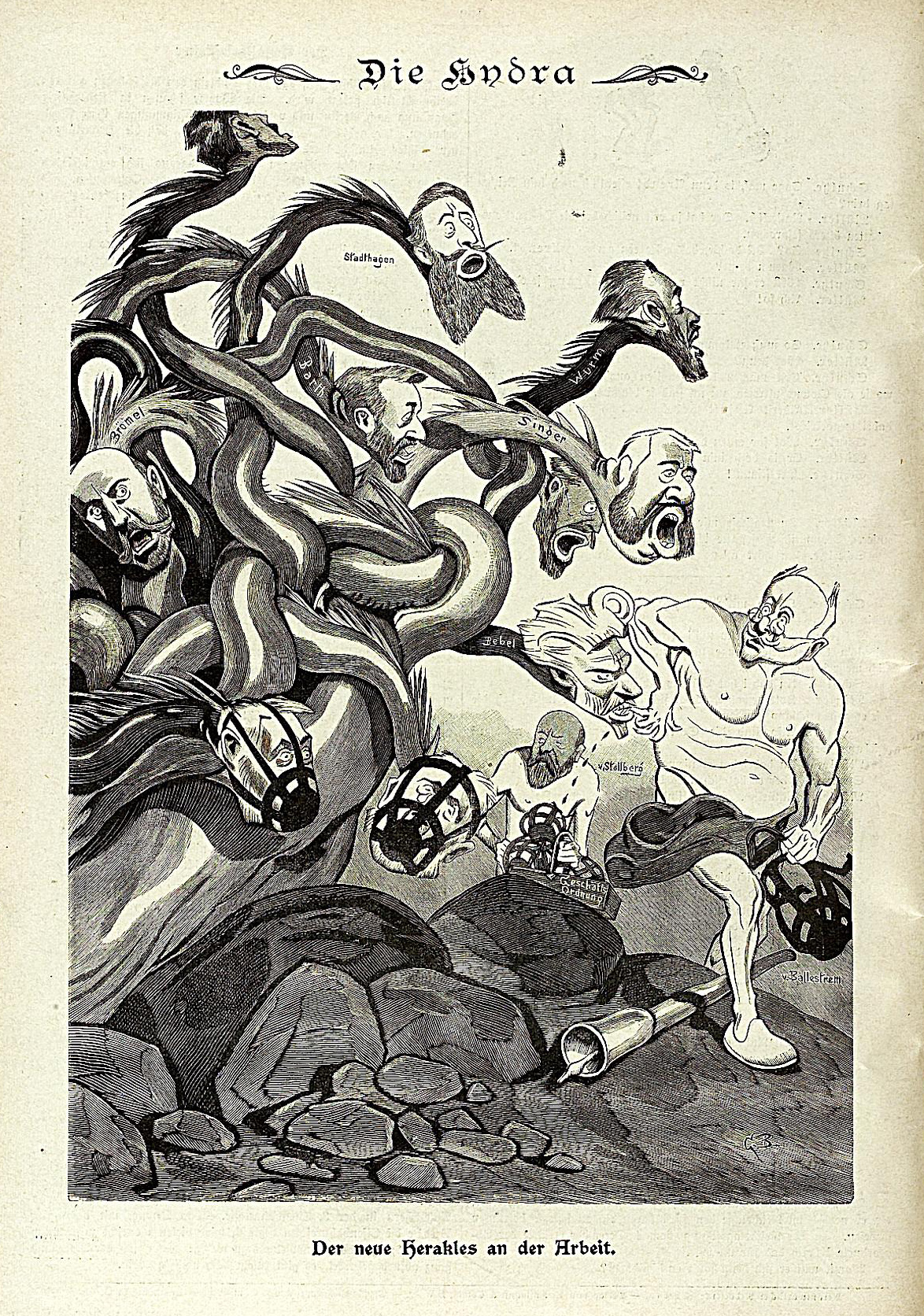

Interior art by Gustav Brandt, 1902

Interior art by Gustav Brandt, 1902

Interior art by Werner Hahmann, 1934

Interior art by Werner Hahmann, 1934

Cover art by Arthur Johnson, 1919

Cover art by Arthur Johnson, 1919

Cover art by Arthur Johnson, 1932

Cover art by Arthur Johnson, 1932

Cover by Arthur Johnson, based on Arnold Bocklin, November, 1913

Cover by Arthur Johnson, based on Arnold Bocklin, November, 1913

Kladderadatsch (onomatopoeic for "Crash") was a satirical German-language magazine first published in Berlin on 7 May 1848. It appeared weekly or as the Kladderadatsch put it: "daily, except for weekdays." It was founded by Albert Hofmann and David Kalisch, the latter the son of a Jewish merchant and the author of several works of comedy. Publication ceased in 1944." - quote source

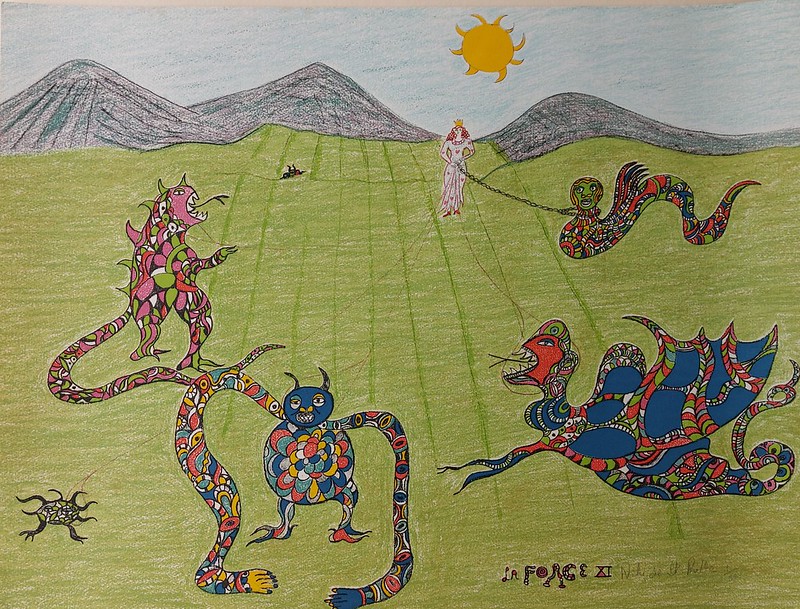

There are a few documentaries on Niki on youtube, "Niki de Saint Phalle Instrospections and Reflections" the other "Niki De Saint Phalle - The story of a free woman" both great ways to discover her larger body of work, including literal buildings in the shape of her art.

There are a few documentaries on Niki on youtube, "Niki de Saint Phalle Instrospections and Reflections" the other "Niki De Saint Phalle - The story of a free woman" both great ways to discover her larger body of work, including literal buildings in the shape of her art.  - source

- source  - source

- source  St George Rescuing a Maiden from a Dragon (Study for a Bookplate)

St George Rescuing a Maiden from a Dragon (Study for a Bookplate)

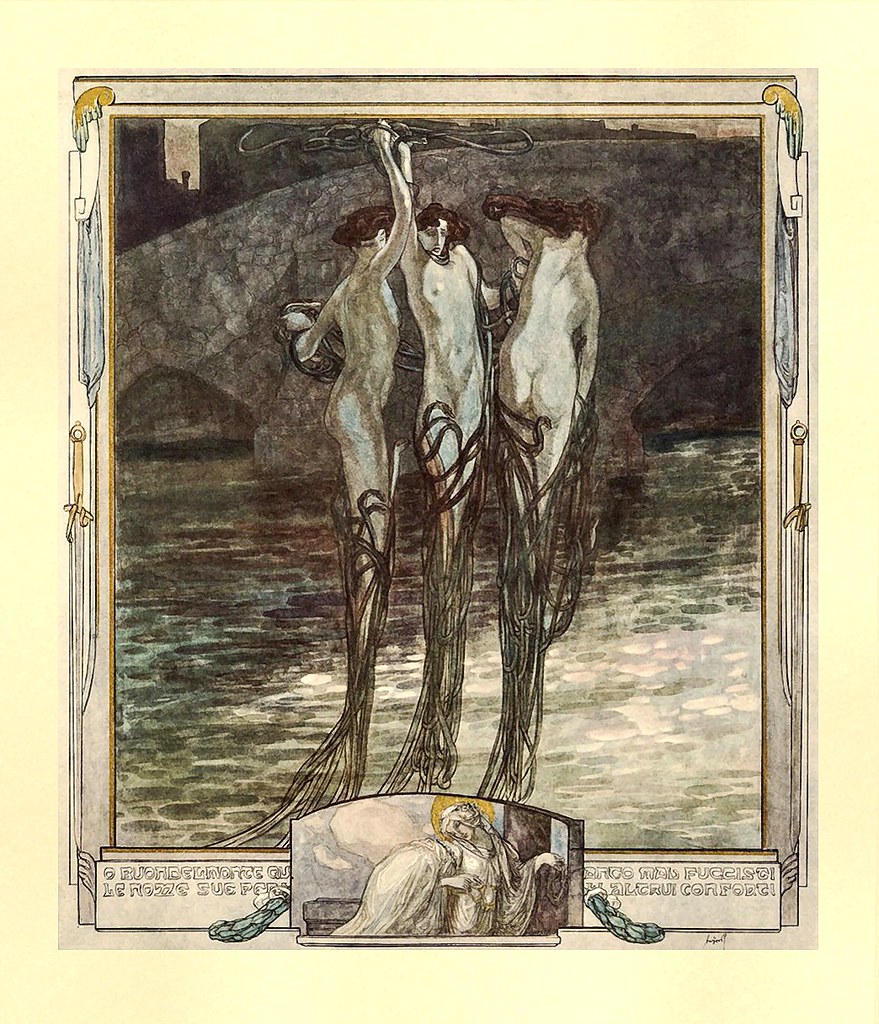

Illustration for Dante Alighieri's 'The Divine Comedy'1921

Illustration for Dante Alighieri's 'The Divine Comedy'1921

Illustration for Dante Alighieri's 'The Divine Comedy'1921

Illustration for Dante Alighieri's 'The Divine Comedy'1921

Illustration for Dante Alighieri's 'The Divine Comedy'1921

Illustration for Dante Alighieri's 'The Divine Comedy'1921

I stumbled onto this book years ago at a used book store. This collection of Bayros's erotic drawings "The amorous drawings of the Marquis von Bayros" is now available on archive.org, check it out here.

Alex Adams / October 6, 2021

In Toho’s 1965 tokusatsu spectacular Invasion of the Astro Monster, humanity makes contact with ruthless hive-mind aliens from Planet X, a new stellar body discovered on the far side of Jupiter. The aliens who inhabit this cold, bleak planet—the Xiliens—are a technologically advanced but blankly unemotional civilization, a race of grey-clad scientists whose remarkable intellectual development has allowed them to live safely underground in the hostile, unwelcoming environment of Planet X. They propose an interplanetary trade: if the world’s authorities—Japan, the US, and the UN—will lend them Godzilla and the fire-hawk Rodan in order to fight off the murderous three-headed space dragon King Ghidorah, who has, of late, become the scourge of Planet X, the Xiliens will provide humanity with the cure for cancer. This trade sounds like a win-win, a blessing, as Earth will simultaneously be rid of its two most troublesome inhabitants and gain a medical miracle. But, of course, it is a cynical double-cross: by stealing Godzilla and Rodan, the Xiliens have captured Earth’s only defences against Ghidorah, who is in fact a living weapon under their control that they plan to use to colonize Earth. Though the “superior” race comes offering gifts, they in fact seek to subjugate and exploit.

Invasion of the Astro Monster is a potent blend of alien invasion, mind control, and interplanetary blackmail. This story, retold several times in the Shōwa era of the Godzilla franchise, is a clear engagement with themes of anti-imperialism and anti-colonialism that were very much current across the globe in the mid-1960s, a decade featuring a panoply of gruesome colonial wars the world over in Algeria, Vietnam, Angola, Kenya, and elsewhere. It is widely acknowledged that Godzilla is, as Ian Buruma writes in the BFI DVD booklet for Ishiro Honda’s original Godzilla (1954), “a profoundly political monster.” But Godzilla’s many sequels are often written off as cheap and goofy cash-ins. Big mistake. Much as US sci-fi movies like The Blob (1958), The Thing From Another World (1951) or Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956) used alien encounters to think through themes of cross-cultural contact, colonialism, and communism, the Shōwa Ghidorah movies are a rich engagement with world-historical themes of Cold War antagonism, first contact, and imperial manipulation.

A History of the DragonGodzilla has long been understood as a powerful symbol of nuclear devastation and the horror of war. While this is true, Godzilla has taken many forms over his seventy-year career, and he has symbolized a great many things. Philip Brophy writes that Godzilla is “less a vessel for consistent authorial and thematic meaning as he is a shell to be used for the generation of potential and variable meanings.” This is true of many of his adversaries too. Monsters have always been tremendously flexible and evocative ways of digesting ideas, fears, and emotions, and Toho’s Kaiju are no exception.

King Ghidorah, an enormous three-headed golden dragon inspired by Yamata No Orochi—a fearsome eight-headed dragon from Shinto mythology—is perhaps Godzilla’s most frequently battled adversary. Along with Mechagodzilla, Rodan, Mothra, and Godzilla, King Ghidorah is one of the cornerstones of the Kaiju Big Five, and his antagonism with Godzilla headlines eight movies, with further variations on Ghidorah also appearing in Godzilla: Final Wars (2004) and the Heisei Mothra trilogy (1996-1998). In the Shōwa period (1954-1975), he is a villain in Ghidorah, The Three-Headed Monster (1964), its sequel Invasion of the Astro Monster, the blockbuster monster brawl Destroy All Monsters (1968), and, as a supporting character, in Godzilla vs. Gigan (1972). In the Heisei period (1984-1995), Godzilla vs. King Ghidorah (1991) would see Ghidorah inflicted on Japan by time-travelling saboteurs—not to mention his cyborgic resurrection as Mecha-King-Ghidorah at the film’s climax. Ten years later, Ghidorah’s role was reversed when he teamed up with Mothra and Baragon to save humanity from Godzilla in Shusuke Kaneko’s Godzilla, Mothra, King Ghidorah: Giant Monsters All-Out Attack (2001). Later in the twenty-first century, King Ghidorah once again features as Godzilla’s arch-nemesis in The Planet Eater (2018), the climactic movie of the Polygon Anime trilogy, and King of the Monsters (2019), the second movie in the ongoing Legendary MonsterVerse. No other monster confronts Godzilla so many times and in so many forms. His Cold War appearances are, thematically, particularly rich and rewarding.

King Ghidorah’s first movie, Ghidorah: The Three-Headed Monster, is a crossover sequel that, through its incorporation of other successful Toho monsters into the Godzilla franchise, was the Avengers: Endgame (2019) of its day. In Rodan (1957), aggressive mining operations awaken a species of enormous and destructive prehistoric birds, and in Mothra (1961) a scientific expedition to Infant Island incurs the wrath of a colossal and beautiful winged insect. Both of these monsters would return in Ghidorah, meshing together their continuities with Godzilla’s and building a wider fictional universe overflowing with Kaiju. Both Rodan and Mothra had a clear environmentalist emphasis, but Mothra is particularly explicit with its political themes. Through its characterization of the greasy capitalist Clark Nelson as an amoral and exploitative villain and its satire of the imperialist nation “Rolisica,” the movie comments on Japan’s geopolitical conundrum: caught between the two nuclear superpowers, striving for more independence from American influence, and balancing the demands of economic prosperity and modernization with the desire to preserve traditional Japanese values. After the runaway success of King Kong Vs. Godzilla (1962/3), which fused monster spectacle with a satire of the advertising industry, Rodan and Mothra too would have their opportunity to confront Godzilla, enriching the franchise with political commentary.

The central themes of power and violence are developed iteratively through the Shōwa monster movies, from the nuclear allegory of Godzilla, the environmental anti-imperialism of the two Mothra films, and on into the Ghidorah movies, which comment much more explicitly on imperial violence and conquest. Mothra’s first sequel, Mothra vs. Godzilla (retitled in the US as Godzilla vs. The Thing) was released early in 1964, and later that year Ghidorah, the Three-Headed Monster hit cinema screens as a winter blockbuster. The movie’s bombastic plot saw the virtuous Mothra persuade the quarrelsome Rodan and Godzilla to team up against the alien peril Ghidorah, a beast more threatening and dangerous than anything anyone had seen before.

Perhaps the single most notable aspect of Ghidorah: The Three-Headed Monster is its lighter, more family-friendly tone. Where once they represented different flavors of doom, Rodan, Mothra, and Godzilla now come to humanity’s aid and are openly celebrated as the triumphant heroes of the hour. This broader tonal appeal has sometimes been read as a disengagement from political themes, as the movie’s crowd-pleasing entertainment value is seen as overriding any attempt to sermonize on social or political matters. Noted Godzilla investigator Steve Ryfle, for instance, writes that in this movie “high-brow issues like nuclear weapons and commercialism are abandoned in favor of pure, fast-paced escapism.” But the central antagonism in the film—the clash between the alien Ghidorah and the trio of cooperating Earthly Kaiju—in fact extends the series’ engagement with international politics even more boldly than the previous entries in the Godzilla series.

In a short tongue-in-cheek article in a 2000 issue of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, Janne Nolan writes that Ghidorah’s first movie works as a compelling example of the benefits of international security cooperation. The movie “is a clear demonstration that even mutants, despite tiny brains and a Darwinian environment, can understand the imperatives of cooperative security when survival is at stake. Maybe policy-makers will be next.” Though Nolan is writing playfully here, this interpretation in fact has much to recommend it. Japan’s post-1945 constitution was written by the occupying US forces, and it placed firm restrictions on Japan’s ability to form an army of any kind. Over the following decades, this constitution and various additional security treaties that were added to it became increasingly controversial and unpopular across the political spectrum, culminating in violent protests in 1960. And there was plenty more happening abroad: China’s regional influence and nuclear weapons program were growing, and China tested its first atomic weapon two months before Ghidorah was released; the USSR was a strong and expanding regional presence; memory of the Korean War was painfully fresh; war raged, bloody and bitter, in Vietnam. Cooperative security, then (however reluctant and fragile), would be a theme that was at the forefront of many Japanese audience members’ minds in 1964.

As we have seen, the sequel Invasion of the Astro Monster (originally titled Godzilla vs. Monster Zero) followed in 1965, omitting Mothra and sophisticating the narrative. Where in his first appearance Ghidorah’s arrival on Earth had been a freak accident, in his second Ghidorah is cynically used against the Earth as part of an overtly imperialist venture by the Xiliens. Similarly, in Destroy All Monsters the Kilaak aliens hijack Earth’s monsters and unleash Ghidorah with the explicit aim of blackmailing humanity into submission. The Kilaaks announce that they come offering peace terms that humanity must accept or die; sacrifices must be made if the Kilaaks are to build the perfect world.

This rhetoric of peace is a particularly evocative element of the films’ representation of imperialism. Roman historian Tacitus famously wrote in Agricola, his history of the Roman conquest of Britain, that the Romans “make a desert and call it peace.” These words are spoken by Calgacus, a Caledonian war leader and resister of Agricola’s conquest, a “barbarian” Briton who Tacitus turns into an eloquent critic of the violence of the Roman Empire. Calgacus’s insight is that the bloodthirsty and warlike Romans, who conquer the entire world through slaughter, slavery, and pillage, cynically describe themselves as benevolent peace-bringers. Indeed, little has changed in the vocabulary of warlike empires: to this day, devastating imperial wars are justified as liberatory and civilizing, as the necessary violence that will bring enlightenment to the dark places of the world. Toho’s Astro-colonizers, too, repeatedly speak the language of peace and cooperation while preparing to annihilate or enslave humanity. In 1972’s Godzilla vs. Gigan (originally titled Earth Destruction Directive), Ghidorah is sidekick to the sinister robotic space-chicken Gigan, and once again both monsters are used against the Earth by an invading force of alien beings, this time the Nebula M aliens. In this one, huge cockroaches masquerading as humans are “striving to bring absolute peace to the whole world.” By this, the Nebula M aliens actually mean that they are plotting the eradication of humanity and the extractive exploitation of Earth’s environment and resources.

“Oh Glenn, I am governed by electronics”This masquerade, in which alien cockroaches appear indistinguishable from ordinary humans, is an interesting thematic overlap with a particularly politically charged Cold War form: the espionage thriller. It is of course no coincidence that the monster stories in Ghidorah movies are often complemented by espionage stories involving the human characters. This was due both to the explosive popularity of 007—Sean Connery had swaggered and snogged his way through Dr. No in 1962 and From Russia With Love in 1963, initiating a global sensation still going strong in 2021—and the rise of Japanese Yakuza crime films that were beloved by audiences. Importantly, many generic elements of Japanese crime and espionage stories (and their Western counterparts) translated particularly well to science fiction, including mind control, subterfuge, infiltration, and double-cross.

Some of the movies’ women are particularly important elements of the Cold War politics of the Shōwa Ghidorah stories. In Invasion of the Astro Monster, American astronaut Glenn’s (Nick Adams) Japanese fiancé Namikawa (Kumi Mizuno) is revealed to be in fact a Citizen of Planet X, where all women look identical—she has been sent by the ashen-faced Commander to seduce and surveil Glenn with the aim of recruiting him to the Xilien cause. Like a sexual temptress from an Ian Fleming novel, she has used her feminine wiles to compromise and manipulate our wisecracking male hero. However, in a campy yet emotionally powerful scene, she defies her programming to declare her authentic love for him—for which crime she is vaporized by her superior. “Our actions are controlled by electronic computers, not by human emotions,” explains the Xilien who coldly murders Namikawa. “When that law is violated, the offender is eliminated.” Likewise, in Destroy All Monsters, Kyoko Manabe (Yukiko Kobayashi) has a small metal receiver implanted into her earrings, and, robotically, she follows the Kilaaks’ every broadcasted command, blithely sowing destruction wherever she goes.

Brainwashing was a major cause of political panic in the late 1950s and early 1960s. American POWs, horribly traumatized by their torture in communist re-education camps, were filmed falsely accusing themselves of war crimes, refusing repatriation, and regurgitating communist propaganda. This extreme ideological indoctrination was dehumanizing, depersonalizing, humiliating, and appeared particularly terrifying because it seemed to show that the human brain could be rewired or manipulated to the extent not only that the prior personality was eliminated but, worse, that the victim appeared either blissfully unaware of or sycophantically grateful for their transformation. Very soon, however, the focus of the political panic sharpened, shifting from the suffering of the captured Americans to the possibility that repatriated soldiers could be reprogrammed into secret assassins whilst appearing, from the outside, to be respectable and well-integrated citizens.

In Richard Condon’s 1959 novel The Manchurian Candidate (famously adapted by John Frankenheimer in 1962), for example, the stepson of a prominent anti-communist senator is brainwashed and used as a remote-control communist assassin. The double agent, unaware of his own programming, is memorably described as “Caesar’s son to be sent into Caesar’s chamber to kill Caesar.” Soon enough, of course, this would shift once more into a more generalized scaremongering about Soviet indoctrination, sleeper agents, and totalitarian mind control that clearly influenced Toho’s Ghidorah movies. The enemy who seems concerned for our safety but who secretly plots our violent demise—the double-crossing double agent, the indoctrinated infiltrator—was a very widespread Cold War bogeyman, and he remains with us today in the modified form of the secretive “lone wolf” terrorist living and moving among us.

“The standard message” of the science fiction film, writes Susan Sontag in 1966’s Against Interpretation, “is the one about the proper, or humane, use of science, versus the mad, obsessional use of science.” Later: “Science is magic, and man has always known that there is black magic as well as white.” The black magic of mind control is one of the most enduring aspects of Cold War political panic. In their attempts to “scientifically” understand Communist brainwashing, the CIA developed the MKUltra program, a set of gruesome torture sessions masquerading as scientific investigations into the limits of human endurance. This program (and the assumptions about the scientific possibility of directing the human mind that underpin it) has continued to have terrible ramifications into the present, as psychologists were brought in to develop the post-9/11 torture program, pseudoscientifically dignifying scandalous mistreatment by presenting it as a controlled and methodical process of scientific investigation. In each of these cases, black magic is not magic at all, but simply, and sadly, torture. Of course, it is overreach to suggest that the Shōwa Ghidorah movies are about CIA torture; but it is clearly true that brainwashing and mind control have always been deeply political concerns.

King Ghidorah: A Political DemonologyThe four Shōwa movies featuring Ghidorah are, then, remarkably thematically consistent. Alien invasion, subterfuge, mind control, and monster cooperation (a kind of Kaiju anti-imperialism) are central to each of them. Most fundamental, however, is the theme of power. Ghidorah is, after all, a King: a total sovereign, breathing fire, exercising absolute and arbitrary power over everything he surveys. It’s true that there is a lot of knockabout fun involved, but the Shōwa Ghidorah movies are also vibrant explorations of authoritarian power, of the political totalitarianism that was so powerful and such an omnipresent concern in the mid-20th century. Importantly, too, a major part of the appeal of the films is their ambiguity. It’s difficult, after all, to say exactly which empire Ghidorah’s villainous commanders are supposed to represent, and, in any case, pinning it down to one definite answer would only diminish the sloshy, sticky generosity of the metaphor.

But it is nonetheless interesting to think it through in terms of concrete possibilities. Since the relationship to the US was a matter of considerable controversy in 1960s Japan, the Astro-colonizers in these movies could well represent America—that most powerful and potentially violent of international actors, the occupier turned ally whose boot was slamming down heavily and noisily in Vietnam. The USSR was also a significant political concern, another expansionist superpower bearing down upon Japan; as we have seen, brainwashing was seen as a specifically communist tactic. But the Cold War period was also marked by precipitous decolonization and rapid, blood-soaked political reconfiguration. The French suffered humiliating and ruinous defeats in Indochina and the Maghreb, most notably in the Algerian Revolution, a bitterly violent conflict abroad that caused the downfall of the Fourth Republic at home. Britain fought dirtily in harrowing counterinsurgency wars in Kenya, Aden, Cyprus, Malaya, and elsewhere. Portugal, too, prosecuted a gruesome campaign in Angola that ended in ignominious defeat. Japan, of course, had its own share of Imperial shame.

Invasion of the Astro Monster makes explicit reference to this global unrest in a startling montage of documentary photography that follows the revelation of the Xilien betrayal.

In the 1960s, cities the world over, including Tokyo, were the stages of protests, unrest, and heavily militarized police crackdowns as groups representing a wide array of new political forces rose up against the established order. This clear visual reference to the global reconfigurations of power that were taking place in the long wake of World War 2 unambiguously situates the Xilien conquest in the tradition of Earthly political upheaval. The Xiliens could be the French, the Soviets, the US, Perfidious Albion—the British Empire—or even the militaristic Japanese Empire of recent memory. Destroy All Monsters, too, set in the utopian future of 1999, shows the fragility of international peace and its vulnerability to imperialist aggression. The futuristic society at the end of the Millennium, dedicated to cooperation and scientific discovery, is still easy prey to the calmly, arrogantly seductive Kilaaks, who are an amalgam of every negative trait ascribed to imperialists: parasitic, violent, manipulative, and smugly convinced of their own superiority. In the final analysis, it is precisely the fact that the Kilaaks, Nebula M aliens, and Xiliens represent imperialism in general, rather than any specific historical constellation, that gives these movies their power.

This condemnation of empire, of course, raises an interesting contradiction, or tension, with relation to the US. One of the defining ideological contradictions of postwar America is that it has managed to present itself as somehow “not an empire” despite its constant projection of militarized power across the planet. The demonization of the tactics of the duplicitous aliens in Invasion of the Astro Monster—a Japan-US co-production—is, for example, clearly in harmony with the political ends of American Cold War neo-imperialist ideology, and serves to cement US-Japan relations as much as it does to criticize them. That is, by using the Xiliens to caricature the crimes of the dying 19th century empires and showing the countries of the democratic capitalist West as an anti-imperial coalition defeating the villains, US-led imperial aggression is painted as a form of humanistic anti-imperialism. The fetishization of anti-imperial resistance is, after all, a core component of contemporary imperial ideology: think Star Wars or any number of similar genre pieces in which plucky Davids smash brutish Goliaths.

In summary, then, the Shōwa Ghidorah films are extraordinary documents of Cold War politics. As they were being made, the old empires were being smashed to the ground, and in the process imperial power itself was problematized and condemned as never before. In this context of global transformation, imperialism itself took on the appearance of senseless, cruel, and openly manipulative barbarism, and imperialists were known more openly as blackmailers, villains, and torturers—or, as Glenn puts it in Invasion of the Astro Monster, as “double-crossin’ finks.” What better metaphor, then, for the arbitrary despotism of empire than a colossal golden hydra remotely controlled by forked-tongued extortionists?

![]() Alex Adams is a writer based in North East England. He writes widely on popular culture and politics, and he is currently writing Godzilla: A Critical Demonology for Headpress Books. Follow him on Twitter at @AlexAdams5 and @GDemonology, or visit his website to read more.

Alex Adams is a writer based in North East England. He writes widely on popular culture and politics, and he is currently writing Godzilla: A Critical Demonology for Headpress Books. Follow him on Twitter at @AlexAdams5 and @GDemonology, or visit his website to read more.

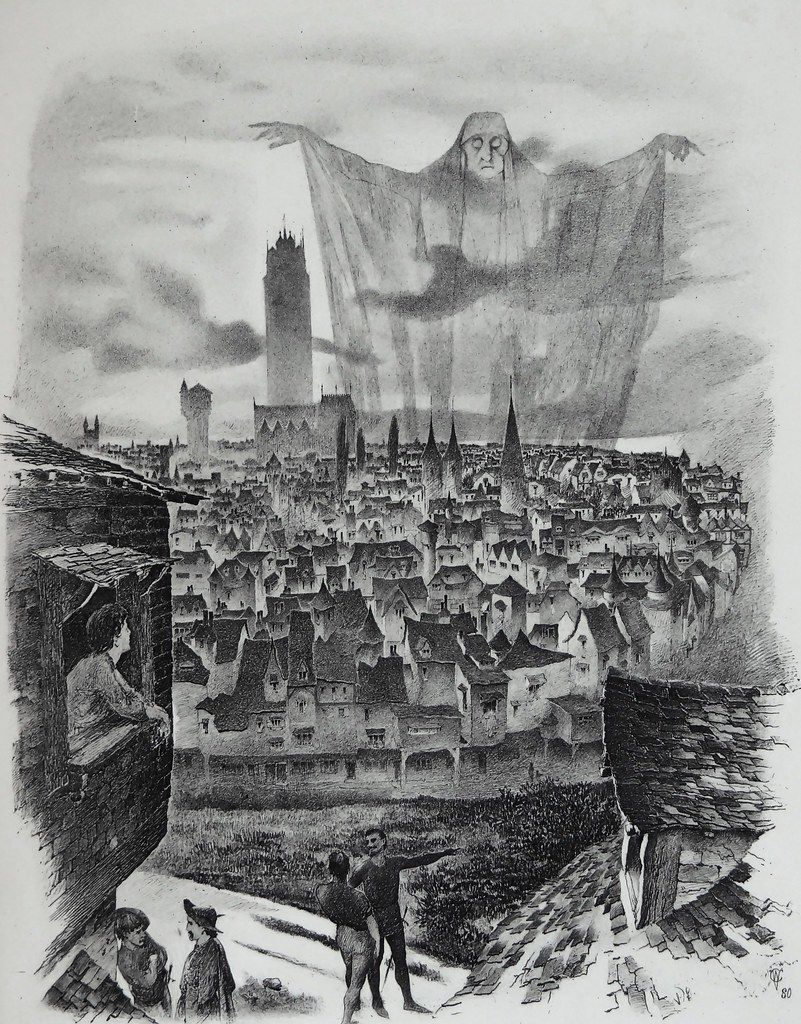

Illustration for "In the sky she saw a vast shadowy figure." from “Under the Sunset” by Bram Stoker, 1882

Illustration for "In the sky she saw a vast shadowy figure." from “Under the Sunset” by Bram Stoker, 1882

Illustration for "Prince Zaphir slays the Giant" from “Under the Sunset” by Bram Stoker, 1882

Illustration for "Prince Zaphir slays the Giant" from “Under the Sunset” by Bram Stoker, 1882

Artworks found thanks to Leo Boudreau.

Piero di Cosimo - Perseus Rescuing Andromeda, 1510-13

Piero di Cosimo - Perseus Rescuing Andromeda, 1510-13

Master of Serumido (from piero di cosimo), Perseus Rescuing Andromeda, 1500-15

Master of Serumido (from piero di cosimo), Perseus Rescuing Andromeda, 1500-15

The Piero di Cosimo artwork was originally shared here in 2007.

The Piero di Cosimo artwork was found thanks to Peter's flickr account. I highly recommend browsing his vast collection of mostly ancient art on up through 18th - 19th century works.

The Master of Serumido artwork was found on Wikipedia Commons.

"Wilhelm Trübner (1851 – 1917) was a German realist painter, greatly influenced by fellow artists Gustave Courbet and Wilhelm Leibl.

Trübner returns to Ancient Greece in a modern, realistic way with his 1891 work, A Gorgon’s Head. The gorgons were Ancient Greek winged female creatures with living snakes as hair and protruding tongues. They would transform to stone anyone who looked at their dreadful faces and place the stone statues in front of their cave as a warning.

Among them, the most known today is the only mortal gorgon, Medusa, killed by the demigod Perseus. Her immortal sisters were Stheno and Euryale. According to Greek mythology, the goddess Athena transformed them into terrible monsters after Medusa was raped by Poseidon in Athena’s Temple. Finding no fault in Poseidon, Athena took her rage on Medusa and on her two sisters who were siding with her.

In spite of Trübner’s take on mythology, he doesn’t idealize or use a large-scale scene as the context for his painting. We don’t even see the gorgon’s body nor have any real indication as to which one of the three sisters he depicts. The head is hovering in space with a drowsy, satiated face expression, the snakes on her head hissing ominously. If we stare long enough at her face, we might be turned to stone." - image and quote source

Image found thanks to Peter's flickr account. I highly recommend browsing his vast collection of mostly ancient art on up through 18th - 19th century works.

Mike Apichella / September 23, 2021

Outside of David Cronenberg’s work and stray oddities like 1980’s The Changeling, the Canadian horror and sci-fi movies of the 1970s and ‘80s often get overshadowed by their counterparts from the US and Europe. Unlike gory scares from other nations, these films reflect the fears of a society deeply impacted and alienated by the goals of close political allies. When viewed through the prism of the Canadian diplomacy that helped diffuse tension during some of the Cold War’s most dangerous moments, America’s patriotic vanity, the remnants of Old World imperialism, and other messy political controversies appear self-destructive and excessive at worst, futile and absurd at best. The 1988 film The Brain presents a grotesque rumination on suburban neurosis, mass media, and Canada’s place in the tangled mass of global politics. A film whose complex special effects, creature designs, dangerous stunts, and high-speed pacing place it a step above many other ‘80s horror works, The Brain is a seamless hybrid of sci-fi adventure and insane spectacle with political symbolism burning at the core of every scene and characterization.

The Brain was directed by Ed Hunt and written by Barry Pearson, two indie stalwarts who’d been active for the better part of two decades by the time of the film’s release. Los Angeles expat Hunt didn’t begin his film career until relocating to Canada in 1969, where his twisted vision brought life to sci-fi/crime hybrid Point Of No Return (1976) and the cult-classic “documentary” UFO’s Are Real (1979). Hunt and Pearson collaborated on several interesting cheapies, including the convoluted but colorful Starship Invasions (1977) and the kids-on-a-rampage flick Bloody Birthday (1981). The Brain premiered in Toronto on November 4, 1988, generating little interest before quickly fading into the blurry late-night glare of cable TV and the home video market.

Much of The Brain was shot on location at Ontario’s Xerox Research Center, a gargantuan example of architectural modernism that looks like a cross between an alien spaceship and a megastadium. Interior scenes are shot with the stark ambience of a morgue, which emphasizes the building’s grim fictional repurposing as headquarters of the P.R.I. (Psychological Research Institute). The faux medical facility functions primarily as the secret hideout for the film’s titular alien monster, a huge, tentacled, telekinetic mutant brain with gaping jaws, beady bulbous eyes, and an insatiable hunger for human flesh. The Brain works hard to control Earth’s population via a hypnotic P.R.I.-produced TV program called Independent Thinking, which is hosted by the creature’s smooth-talking lackey Doctor Blakely (David Gale of Re-Animator fame) in the guise of a Tony Robbins-like motivational speaker. Unbeknownst to its loyal viewers, however, the broadcast progressively drains their free will whenever it airs.

This process is illustrated when mischievous science prodigy Jim Majelewski (the smirking, Ferris Bueller-ish Tom Brezahan) is punished by his high school principal after one prank too many. The uptight administrator (Kenneth MacGregor) orders Majelewski to get psychiatric treatment at P.R.I. or face expulsion from school. When Jim arrives at the site, he’s greeted by silence and the cold stares of line upon line of emotionless Independent Thinking audience members and P.R.I. “patients,” his wisecracks answered only by the surly mumbling of security guards. P.R.I. isn’t so much a medical entity as it is a psychic meat processing plant where victims are primed for consumption by the operation’s grotesque mastermind.

The giant Brain draws power from the sheep-like “independent thinkers,” whose loyalty springs from the desperate search for an efficient solution to everyday suburban problems—workplace stress, financial woes, marital dramas, and, most of all, raucous teens and juvenile delinquents. Much of the program’s loyal fan base is made up of educators, school administrators, police, and parents, who represent the authority figures who struggle with huge moral decisions that can make or break young lives. They flock like lemmings to the fluffy pop psychology of Independent Thinking and its glorious potential as a universal stress remedy.

Even before Majelewski discovers the grim secret of P.R.I.’s “therapeutic” behavioral modification, he’s shown to be one of the few people who refuse to watch Independent Thinking, and he frequently tries to stop friends and relatives from watching once he notices the show’s damaging mental effects. When P.R.I. thugs and other local authoritarians take note of his disruptive influence, the teen becomes a target and is forced to go on the lam. In the film’s most 1984-esque twist, there’s even a short, PG-rated love scene that occurs while Majelewski and his girlfriend Janet (Cynthia Preston) hide from pursuers in a shuttered school library, a structure dedicated to knowledge and enlightenment—both of which are subverted when Majelewski wakes up the next morning to find Janet watching TV, mesmerized. The latest episode of Independent Thinking comes on, featuring a false portrayal of Majelewski as a psychotic serial killer. Janet starts screaming her head off and rushes out of the library to alert authorities, revealing that the Brain’s power can instill emotional instability just as well as destructive passivity,

Although The Brain does offer something of a critique of the power of television, it does not demonize the medium, much to its credit. The plot revolves around the idea that mass media can only be destructive in a society that refuses to question its authority. What saves Ontario (and ultimately the world) from mass zombification is not technology or Luddism, but Majelewski’s emotional concern for the well-being of his community. Conversely, the monstrous Brain and its violent appetites are cold-blooded and antisocial in the extreme: the creature treats people—from TV audiences, to unsuspecting home viewers, to Dr. Blakely and other acolytes—like interchangeable tools to be used and abused at will (that is, of course, when it’s not busy eating every living thing in sight). The monster is ego and gluttony, a combination of crazed dictator and rabid animal.

That brutal inhumanity is fleshed out in growling, spitting, drooling visuals inspired by a patchwork of iconic sci-fi influences: bits of Audrey II from Little Shop Of Horrors, rubberized ‘50s sci-fi monsters (with nods to 1957’s The Brain from Planet Arous and 1958’s Fiend Without a Face), and Dark Crystal-esque acid nightmares all congeal in the gooey weirdness of the effects work of Mark Williams and Daniel White. Roaring aerodynamic attacks tear across the screen thanks to “brain operators” Chris Thiesenhausen and Phillip M. Good (who doubled as assistant producer), the monster’s cartoon fury providing a perfect contrast to the tragic vulnerability defining many of the characters who fall under its telekinetic death spell.

The Brain’s predictably noisy, ultraviolent demise is contrasted by an unexpectedly subtle final scene. All we see is a quiet, overcast day in an inconspicuous suburban development as victims and protagonists decompress. It works equally well as the set up for a sequel or as an extra layer of political symbolism. There’s no fanfare, no triumphant hard rock anthem blasting over the end credits. Grey skies and contemplation are all that can accompany the calm and unease—and vigilance—born of the Brain’s strange aftermath.

![]() Mike Apichella has been working in the arts since 1991. He is a writer, multimedia artist, musician, and a founder of Human Host and the archival project Towson-Glen Arm Freakouts. Under his real name and various pseudonyms, his work has been published by Splice Today, Profligate, Human Conduct Press, and several DIY zines. Mike currently lives in the northeast US where he aspires to someday become the “crazy cat man” of his neighborhood.

Mike Apichella has been working in the arts since 1991. He is a writer, multimedia artist, musician, and a founder of Human Host and the archival project Towson-Glen Arm Freakouts. Under his real name and various pseudonyms, his work has been published by Splice Today, Profligate, Human Conduct Press, and several DIY zines. Mike currently lives in the northeast US where he aspires to someday become the “crazy cat man” of his neighborhood.

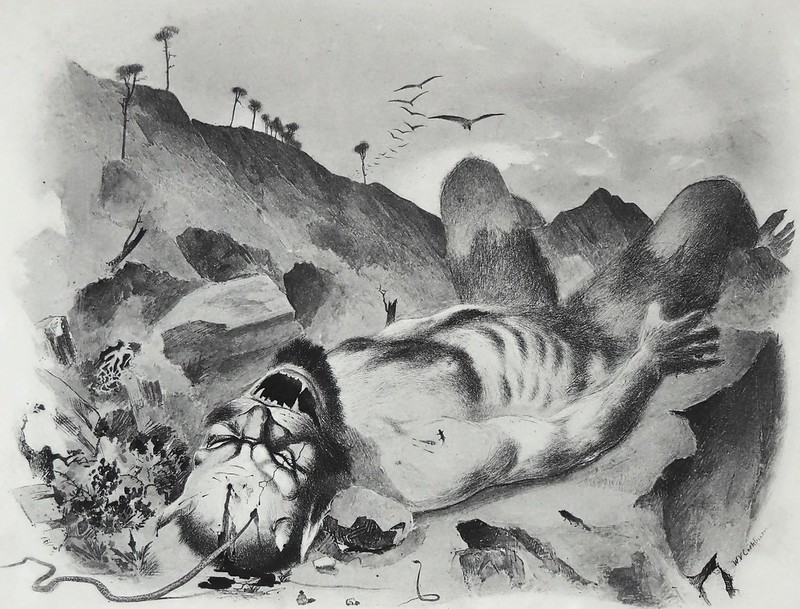

Artwork found at SMK Open.

Artwork found at SMK Open. This illustration is reproduced in the tribute collection The Fantastic Art of Clark Ashton Smith by Dennis Rickard (Mirage Press, 1973).

If you are interested in owning this original Clark Ashton Smith drawing, it is currently available through the Heritage Auctions website. It is attached to an auction in early October. The full page with all related information at the Heritage Auction website can be viewed here.

I previously shared the art of Clark Ashton Smith in 2006 with a thumbnail of this artwork here.