Andrew Nette / February 17, 2021

In a June 2017 article in Fortean Times, the British magazine concerned with strange and paranormal phenomena, writer and broadcaster Bob Fischer discussed how the sensation of not being exactly sure what you were watching on television, or not being able to recall the details with any precision, was a common experience in relation to consuming visual culture in the 1960s and 1970s, before the advent of streaming, DVD, and VHS. This sense of “lostness”—of incomplete and unverifiable experience—is also what makes these memories such powerful nostalgia prompts.

The television viewing experience that most encapsulates this sense of lostness for me is a little-known, American-backed, Australian-made horror anthology series, The Evil Touch, that debuted on Sydney screens in June 1973 and in Melbourne a month later. Largely forgotten now, American critic John Kenneth Muir referred to the show in his 2001 book, Terror Television: American Series 1970-1999, as the “horror anthology that slipped through the cracks of time.” The Evil Touch has never had an official DVD release, although poor quality versions of some episodes can be found online, or as bootleg editions originally copied from television on VHS. It is not even known who now owns the rights. But the program was significant in many ways.

From the late 1950s to the early 1960s, Australian television programming was dominated by cheap to purchase overseas productions, mainly from the United States. While the balance started to shift starting in the mid-1960s, when demands for more Australian-made content grew louder, American product still dominated, and few Australian shows were sold overseas. The only Australian-made television show sold to the United States during this time that I am aware of is The Evil Touch. Produced in Sydney specifically for the American market, it was shot in color on 16mm film at a time when local television was still black and white; the first color broadcasts in Australia did not occur until 1974, and color did not roll out nationally until 1975.

The Evil Touch was also unusual for being the only locally produced entry in the once highly popular canon of horror anthology television. The anthology horror format, in which each episode is a different story with a new set of characters, originated in the 1950s, increased in popularity in the 1960s with programs such as The Outer Limits (1963-1965) and Rod Serling’s The Twilight Zone (1959 to 1964), and peaked in the 1970s. Debuting in 1970, Serling’s Night Gallery, a series of one-off stories with macabre and supernatural plots, was the beginning of modern horror television. Numerous shows followed in America, and anthology horror also proved popular in Great Britain, most notably the 1976 series Beasts, written by Nigel Kneale (who had scripted earlier science fiction television series and films featuring the scientist Bernard Quatermass), consisting of six self-contained episodes, each with a recurring theme of bestial horror.

The Evil Touch was also unusual for being the only locally produced entry in the once highly popular canon of horror anthology television. The anthology horror format, in which each episode is a different story with a new set of characters, originated in the 1950s, increased in popularity in the 1960s with programs such as The Outer Limits (1963-1965) and Rod Serling’s The Twilight Zone (1959 to 1964), and peaked in the 1970s. Debuting in 1970, Serling’s Night Gallery, a series of one-off stories with macabre and supernatural plots, was the beginning of modern horror television. Numerous shows followed in America, and anthology horror also proved popular in Great Britain, most notably the 1976 series Beasts, written by Nigel Kneale (who had scripted earlier science fiction television series and films featuring the scientist Bernard Quatermass), consisting of six self-contained episodes, each with a recurring theme of bestial horror.

The central figure behind The Evil Touch was silver-haired expatriate American television director and producer Mende Brown. Brown formulated the idea for the series, produced all 26 episodes, and directed 15. According to his 2002 obituary in Variety, he was born in New York, started in radio after World War II, and his first directing credit was a 1953 episode of the popular radio show Inner Sanctum Mystery, produced by his brother Himan. Working in film and television throughout the ‘50s, his first feature directing job was The Clown and the Kids in 1967, noteworthy for being shot entirely on location behind the then Iron Curtain in Bulgaria, with the cooperation of the country’s state film body.

Variety’s obituary dates Brown’s move to Australia as 1971, but other sources suggest he arrived in 1970. Either way, he soon set up his own company, Amalgamated Pictures Australasia, operating out of an office in Sydney’s then vice quarter Kings Cross, which at the time also played host to a large number of American service personnel on R&R during the Vietnam War. From this base of operations, Brown oversaw a number of projects prior to The Evil Touch. He directed and produced Strange Holiday (1970), based on Jules Verne’s 1887 novel A Long Vacation, and Little Jungle Boy (1971), a made-for-television children’s film shot in Singapore. In 1973, Brown also wrote and produced And Millions Will Die. Made in Hong Kong, the story pitted popular American television actor Richard Basehart, best known for playing Admiral Harriman Nelson in the science-fiction adventure television series Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea (1964-1968), as a secret agent battling a Nazi germ warfare expert who threatens to unleash a lethal gas on the British territory.

The Australian Women’s Weekly described Brown as “An American TV producer and director who has decided that Australia is a good place to make films.” Emanuel L. Wolf, president and chair of Allied Artists Picture Corporation, which backed The Evil Touch to the tune of A$250,000, put it more bluntly when he visited Sydney to discuss possible film and television deals in August 1972. He told journalists there was a great advantage to making films in Australia because the costs were substantially lower, and the work restrictions were considerably less than those enforced by entertainment unions in America. At the cost of A$30,000-40,000 per episode, The Evil Touch was a glamorous, big budget affair by local standards, and a host of American television/film actors travelled down under to star in, and sometimes direct, episodes. “Never has Australia been so inundated with so many top name American movie stars,” declared the Australian magazine TV Week on August 4, 1973. In reality, most of these individuals were long past the peak of their careers; but in Australia, which was only just developing a domestic film industry of its own, they remained big names due to the continuing proliferation of American shows on local television. Many of them were also desperate for work, given the economic difficulties facing the American film and television industry in the early 1970s. “American actors are happy to come here, both for the money and the work,” Brown told a press conference to announce The Evil Touch in Sydney in October 1971. “They’re delighted to work anywhere they can get it.”

Brown milked the publicity generated by his overseas cast for all it was worth. Australian magazine and newspaper coverage from the time records a steady drum beat of fascination with visiting stars: Leslie Neilson; veteran actor Leif Erickson, familiar to Australian audiences as a cast member of the TV western High Chaparral (1967-71); Ray Walston, known as the Martian in My Favorite Martian (1963-66); and Vic Morrow, star of Combat (1962-1967). Others included Darren McGavin, US child model turned actress Carol Lynley, Susan Strasberg, Robert Lansing from Gunsmoke (1965-1969), and Julie Harris, whose career stretched back to the late 1940s and included a role in Robert Wise’s eerie 1963 ghost film The Haunting.

One lesser-known international actor to feature in The Evil Touch was Mel Welles. After appearing in television series and B movies in the US in the 1950s, Welles spent much of the 1960s in Europe, where his directing credits included the now infamous 1971 Italian horror Lady Frankenstein, a weird exploitation riff on Mary Shelley’s 1818 Gothic novel. The early 1970s saw him in Japan for a small role in a local science fiction action series, after which he found himself in Australia, where he appeared in one episode of The Evil Touch, “Wings of Death,” about an Australian family whose son disappears while they are travelling in an unspecified Latin American country. Welles plays a sleazy cop who heads up the local death cult that, unknown to the parents, has kidnapped the child. Having discharged his obligations to Brown, Welles spent his time organizing the only Australian showing of Lady Frankenstein, at Kings Cross’s Metro Cinema. To accompany this, he organized a live stage show titled “Orgy of Evil,” a self-styled history of nudity, violence, and torture. An advertisement in the Sydney Morning Herald in July 1973 billed the show as “A live stage presentation of evil, terror and horror beyond the mortal imagination.” It reportedly cost a fortune to mount, attracted the unwelcome attention of the city’s vice squad, and closed after only a week, at which point Welles fled the country.

In addition to American acting talent, American writers penned all but three The Evil Touch scripts. One of those writers was Sylvester Stallone, who was then trying to break into Hollywood. According to IMDb, he scored his first writing credit on an episode of the show under the pseudonym “Q Moonblood.” The US-centric nature of the show landed Brown into trouble with local entertainment unions, who threatened an international campaign against The Evil Touch. Brown was forced into negotiations, Variety reporting in early 1973 that his company reached an “entirely equitable agreement… Basically that is that one American star can be imported for each episode, with one Australian player to be co-starred and others featured.” As a result, the show played host to a plethora of local actors who went on to become major names in home-grown film and television.

The Evil Touch screened throughout America in late 1972 and, according to Variety, rated well. Australian viewers were far less taken with the show, however, and it lasted only a few episodes on Channel 9 before being dropped from the schedule. Heavy-handed censorship meant that horror was not a genre with particularly deep roots in local television or film, so audiences were possibly unaccustomed to it. Yet in Australia, as elsewhere, the 1970s were the era when Erich von Däniken’s Chariots of the Gods? was a staple of many bookshelves, when the occult became a suburban preoccupation, and when mysteries such as the Bermuda Triangle, UFOs, and the Loch Ness Monster were popular tabloid fodder. As such, The Evil Touch’s lack of success probably had more to do with its main competitor, the soap opera Number 96, which screened at the same time on rival Channel 0 (now 10). This featured the salacious goings on in an inner-Sydney block of flats, complete with ground-breaking television depictions of nudity and sex, including Australian television’s first gay kiss.

The Evil Touch continued to turn up regularly on late night television in Australia throughout the 1970s and 1980s, when I am fairly sure I saw my first episode, most likely left unsupervised with the television in someone’s den during one of the many boozy dinner parties my parents attended. The few grainy episodes I caught haunted me for years, even though I wasn’t exactly sure what I had seen. Indeed, until I started researching the show for a film festival presentation in 2016 and found some old episodes on YouTube, my memories of The Evil Touch were so blurred and uncertain, I wondered whether I’d just imagined it.

The one image I always remembered from The Evil Touch was its prologue. Each 25-minute episode followed the basic structure and tropes of 1970s anthology horror television. This included a mysterious host, in The Evil Touch’s case British actor Anthony Quayle. To the jazzy lounge music score of Australian composer Laurie Lewis, each episode opened with Quayle walking forward through swirling, multi-colored smoke (produced by holding a lit cigarette just below the camera) to briefly introduce the story. He would appear again at the episode’s end with some concluding remarks and an ominous farewell: “Until next week this is Anthony Quayle, reminding you there is a touch of evil in us all.” He would start to walk away, stop, and turn back and mischievously say, “Pleasant dreams.”

Host Anthony Quayle

Muir links the popularity of the anthology horror format in America in the early 1970s to several factors, which were echoed in Australia: the relaxation of censorship standards, which allowed shows to get away with more explicit horror and violence; advances in make-up and special effects; and the shift in the national mood due largely to the shocking prime-time news footage coming out of the Vietnam War. “Vietnam and Watergate were two turbulent and controversial public events which America had to digest,” he writes, “and horror television responded with a cathartic form of entertainment that acknowledged national fears yet reinforced positive values.” If there is a thematic strand running through 1960s/1970s anthology horror television, it is the sense of an otherworldly moral judge and jury operating to punish murderers, adulterers, and greedy businessmen for crimes they would otherwise get away with. The Evil Touch ran the gamut of genres, from science fiction to mystery murder tales, to horror, but nearly all the episodes utilize this punitive narrative form.

Less characteristic of the television anthology horror genre was The Evil Touch’s surreal, dream-like quality, and its deliberately non-linear storytelling style. With the exception of Quayle’s omniscient and enigmatic introductions and conclusions, the characters and events in each episode are given little context and there is usually no sense of narrative closure. The strange ambience of The Evil Touch is also the product of its generic setting, a deliberate strategy on Brown’s part to maximize its appeal to American audiences. While mostly shot in or around Sydney, landmarks and characteristics that could have been recognizable are de-identified. As TV Times put it in 1973: “The Evil Touch was made in Australia, but unless you recognize familiar faces among the bit players you might not suspect this, for by using cunning devices such as reversing film negatives, producer-director Mende Brown shows right hand drive cars belting through Sydney on the wrong side of the road.” To a local watcher, the overall effect is unnerving: Australia rendered largely anonymous for American viewers, almost a fulfilment of fears, dating back to the 1920s on the part of local left- and right-wing critics, that Australia would be subsumed by American popular culture. A particularly vocal critic was The Age’s television critic John Pinkney who, in a July 1973 column, lambasted the show’s American dominated look and feel, in particular the fact that Australian actors were required to speak with US accents. “Evil Touch conjures the Commonwealth of Oz into the status of a non-county,” he wrote.

In the aforementioned episode “Wings of Death,” outer Sydney stands in for a nameless Latin American republic. In “They,” an academic and his young son are vacationing in the Cornish countryside (most likely the cliff tops overlooking Sydney Harbour). The son gets lost on “the moors” and runs into a malevolent cult of ghostly children led by a creepy young woman, who he has already seen in his dreams. In what is undoubtedly a comment on the new forms of youth culture that were sweeping much of the world by the early 1970s, the group she leads has given up the “Old Ones”—anyone over the age of 15—and is also responsible for a string of deaths in a nearby town. “The Fans,” set in the American deep south, sees Vic Morrow as a cynical horror movie star who visits two elderly female fans as a publicity stunt. They drug him, dress him in his screen vampire persona, and imprison him in the basement of their large manor house in an attempt to drive the devil out of him. “The Trial” involves a rapacious property developer (Ray Walston) being pursued through an abandoned carnival ground (Sydney’s Luna Park) by a pack of circus freaks led by a discredited brain surgeon who lobotomizes him, in what feels like a macabre homage to Tod Browning’s 1932 horror classic Freaks.

The only episode obviously shot outside Sydney, “Kadaitcha Country,” is possibly the strongest. Leif Erikson plays a washed-up Christian preacher, who it is inferred has significant mental health issues. Given one last chance at redemption by his church, he is sent to a remote outback mission, where he clashes with an Aboriginal shaman (the “Kadaitcha Man”) who has the power to play with reality. While English spellings of the name vary (either “Kurdaitcha” or “Kurdaitcha”), it appears to refer to a type of shaman/sorcerer who lived among the Arrente people near Alice Springs in central Australia. There are also records of the term “Kadaitcha” being used to refer to Aboriginal law keepers. The episode was directed by Brown and written by Australian Ron Mclean, one of only two local writers to work on the show. The story fuses Indigenous myth (or at least a white director’s interpretation of it) with folk horror tropes in a way that would not be seen on cinema screens until Peter Weir’s The Last Wave in 1977. Not only does the episode rank as an early depiction of the clash between Indigenous spirituality and invading Christian faith, it also featured an Indigenous actor: Lindsey Roughsey, one of the traditional custodians of Mornington Island in the Gulf of Carpentaria, where the episode was filmed, played the Kadaitcha Man. This was something of a breakthrough, as it was not uncommon, well into the 1970s, to have white actors play Indigenous parts in black face.

Mende Brown would go on to produce one further film in Australia, a little-known hardboiled thriller, On the Run (1983), about an orphaned boy sent to live with his uncle (an aging Rod Taylor), who unbeknownst to the boy is a ruthless assassin. It was never released theatrically. Brown returned to the United States in 1991 and died in 2002. Episodes of The Evil Touch continued to rerun on television throughout the 1990s, from America to Japan and Malaysia, like ghostly messages relayed from a long-abandoned outpost of 1970s popular culture.

Andrew Nette is a writer of fiction and non-fiction. He can be found at www.pulpcurry.com.

Andrew Nette is a writer of fiction and non-fiction. He can be found at www.pulpcurry.com.

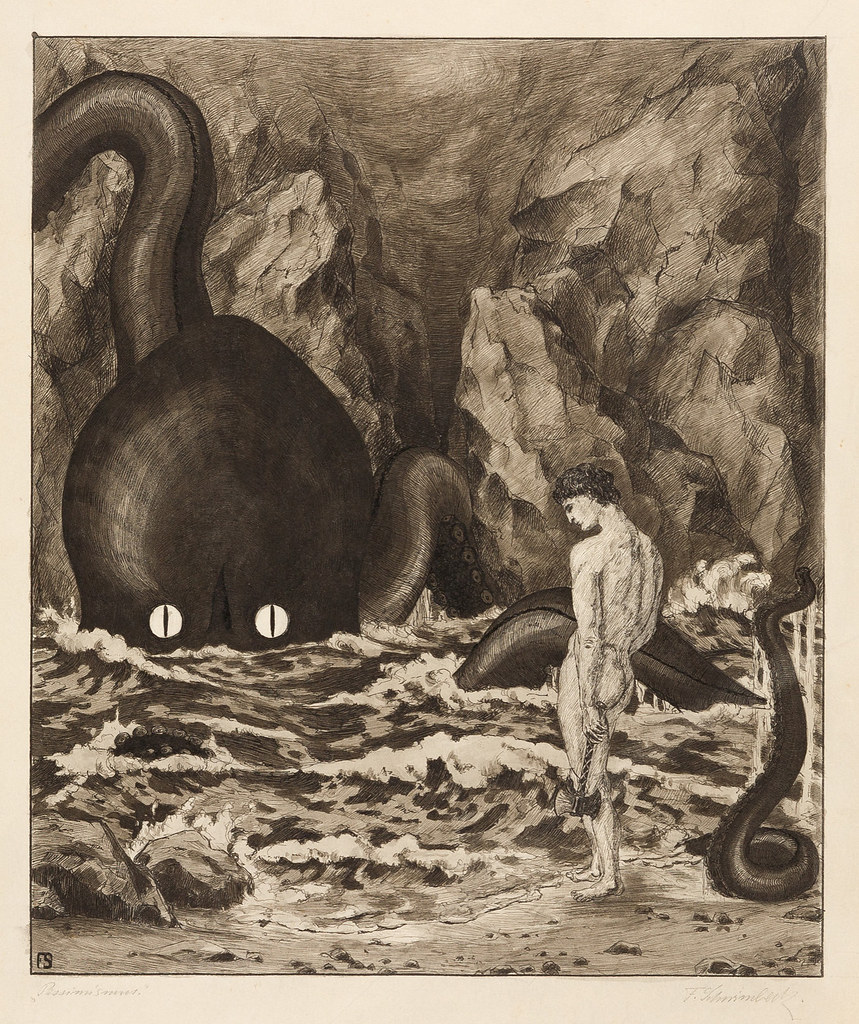

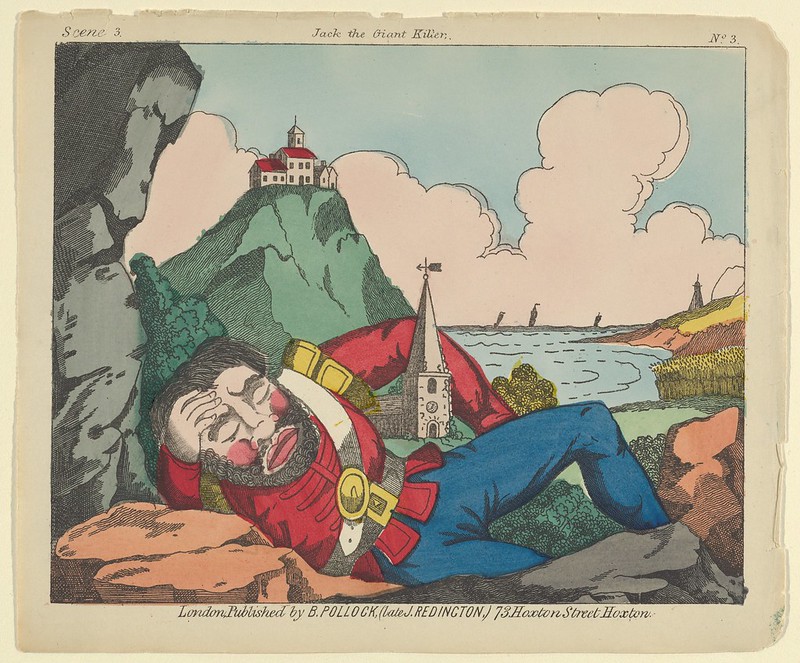

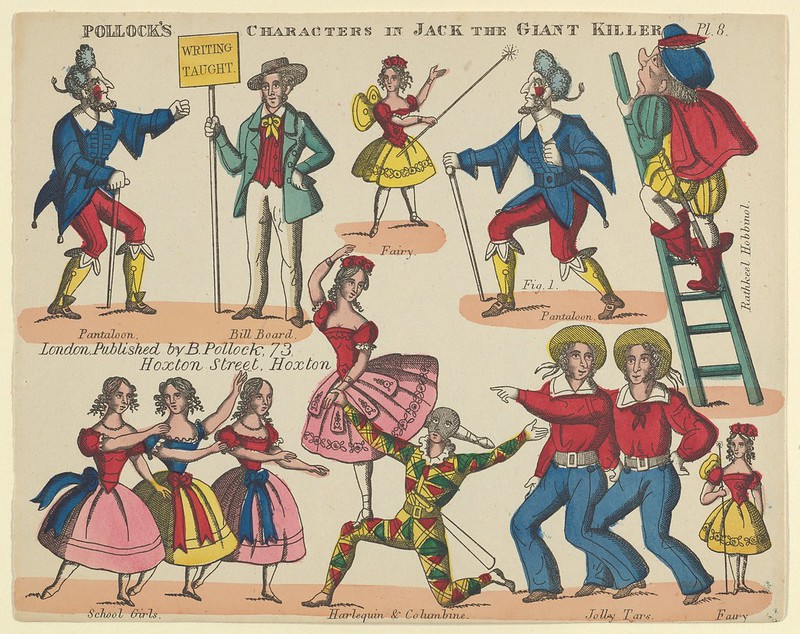

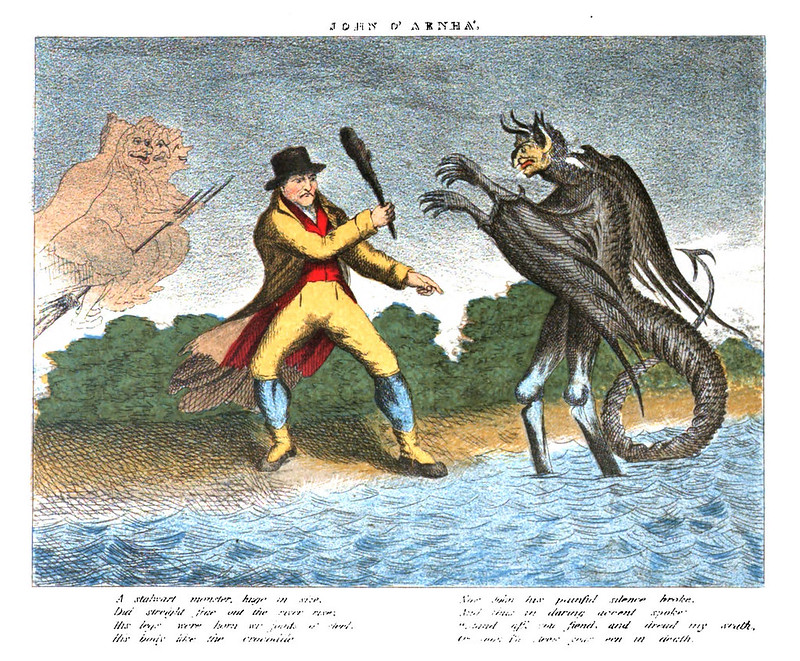

"A stalwart monster, huge in size, Did streight frae out the river rise, His legs were horn, wi joints o' steel, This body like a crocodile..."

"A stalwart monster, huge in size, Did streight frae out the river rise, His legs were horn, wi joints o' steel, This body like a crocodile..."

"Grim furies spread their forkit fangs, An drove at John wi furious bangs..."

"Grim furies spread their forkit fangs, An drove at John wi furious bangs..."

"The Kelpy tried we John to grapple, But Arn caught him by the thrapple, And gar'd his carcase sweep the stanners, Whilk made a noise like corn fanners..."

"The Kelpy tried we John to grapple, But Arn caught him by the thrapple, And gar'd his carcase sweep the stanners, Whilk made a noise like corn fanners..."

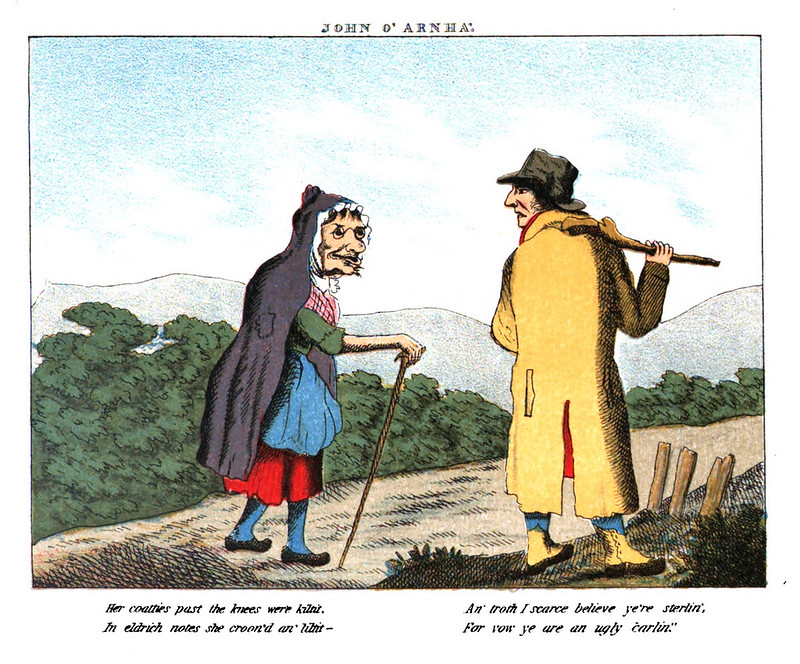

"Her coatties pat the knees were kiltit, In eldrich notes she croone'd an' liltit..."

"Her coatties pat the knees were kiltit, In eldrich notes she croone'd an' liltit..."

"Sae fently did she wing her flight, In a twinklin' she was out o' sight... "

"Sae fently did she wing her flight, In a twinklin' she was out o' sight... "

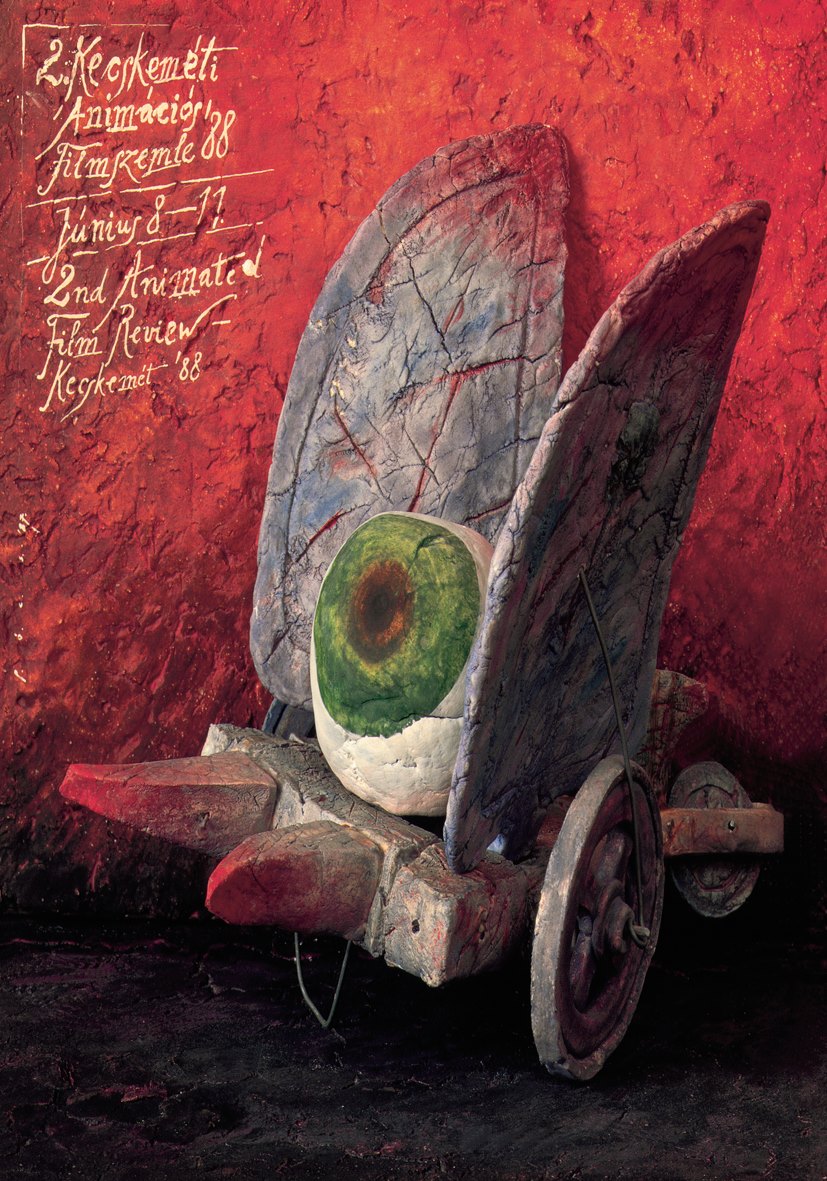

![a lay of the Higher Law. Translated and annotated by ... F. B. [i.e. Frank Baker, pseudonym of Sir R. F. Burton; or rather, written by Sir R. F. Burton.]]](https://live.staticflickr.com/65535/50992970288_7cbf6e69ee_h.jpg)