Art & Illustration

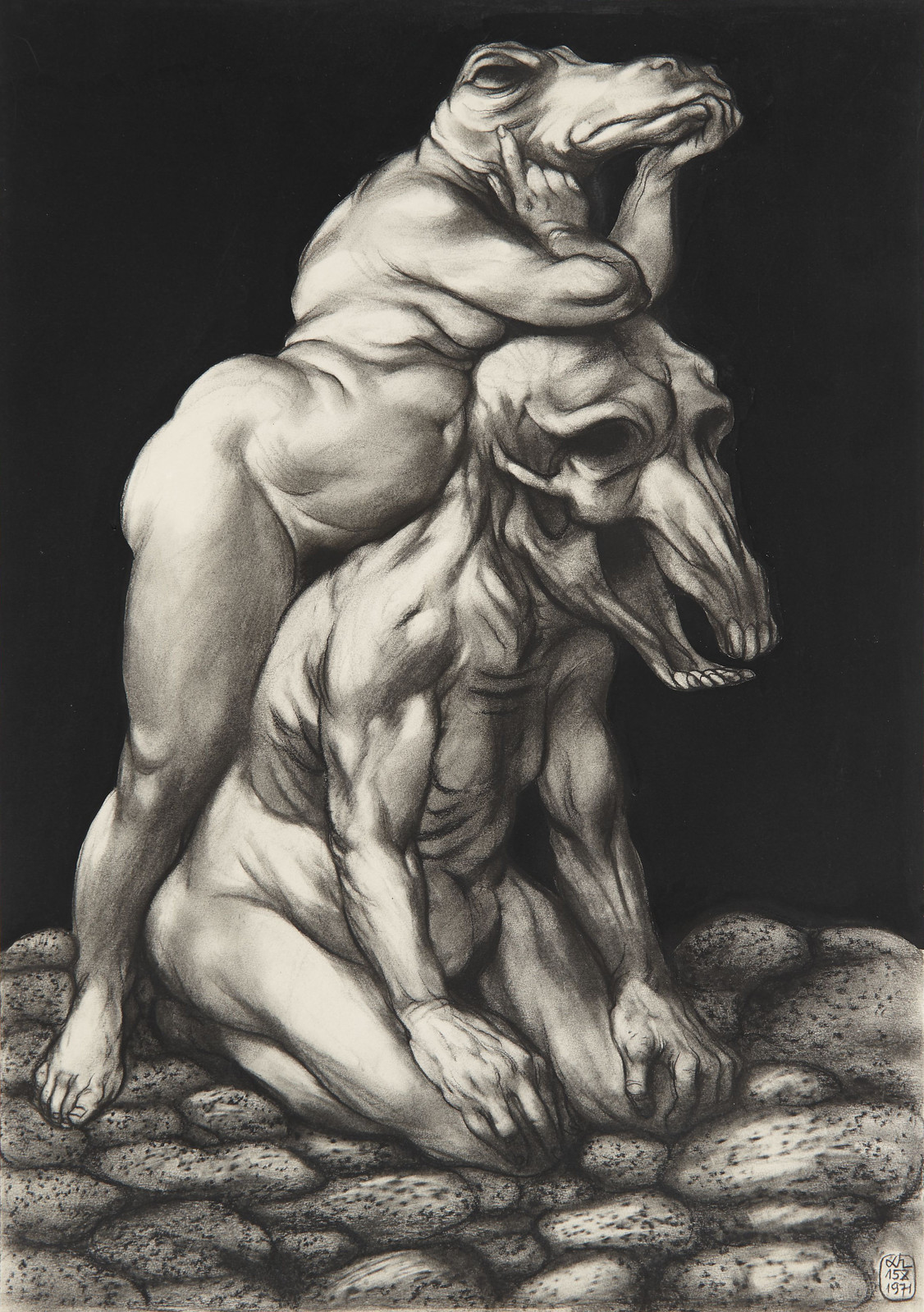

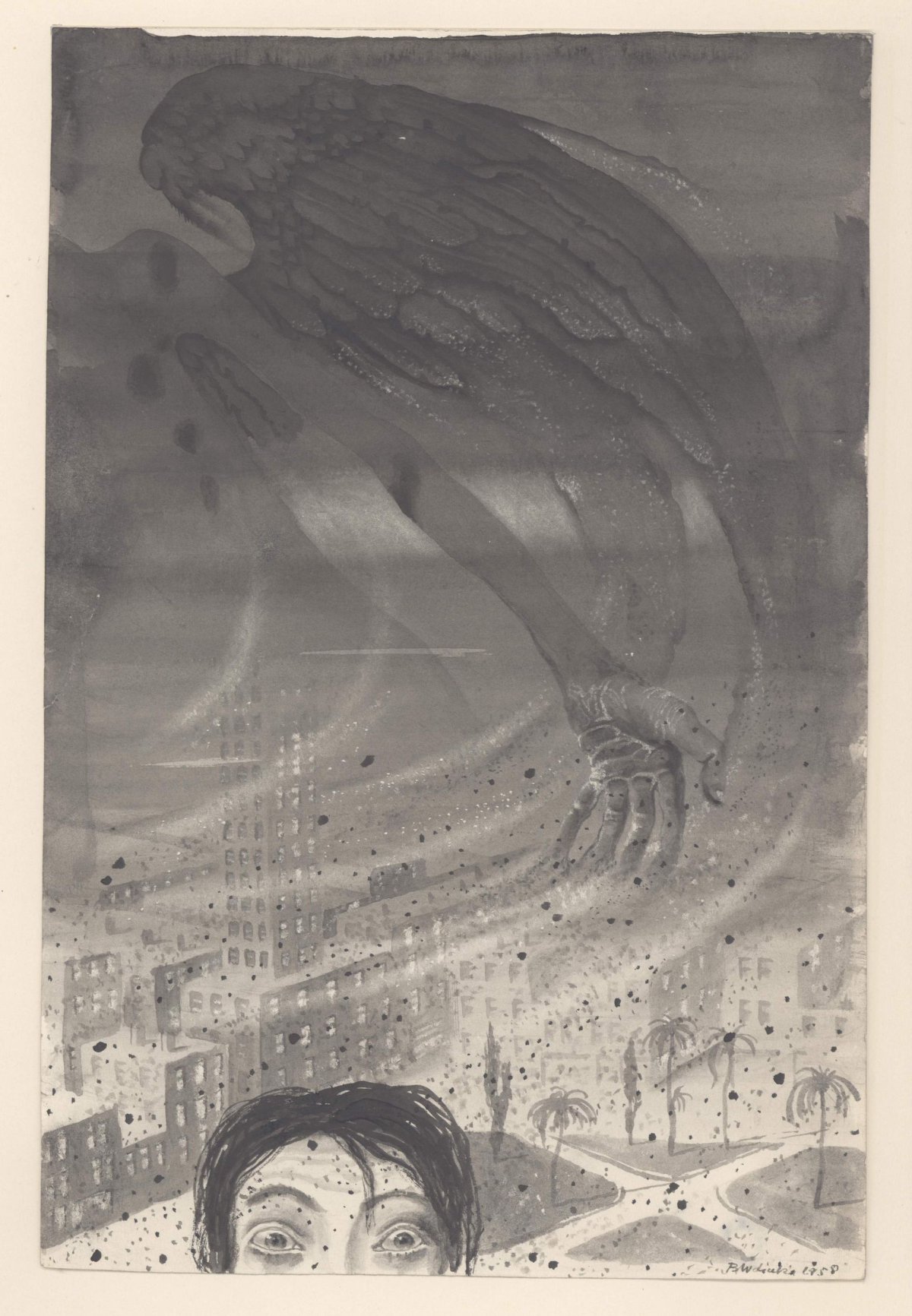

Bronisław Wojciech Linke (1906 - 1962)

Execution In The Ruins Of The Ghetto, 1946

Execution In The Ruins Of The Ghetto, 1946

"In the service of humanity" from the series "Atomium", 1958

"In the service of humanity" from the series "Atomium", 1958

Rainy Weather, from the series "Screaming Stones", 1946

Rainy Weather, from the series "Screaming Stones", 1946

"Luftwaffe" from the series "Stones Shout", 1948

"Luftwaffe" from the series "Stones Shout", 1948

Team, illustration for the book "Conversations With Silence" by Pola Gojawiczynska, Warszawa, 1936

Team, illustration for the book "Conversations With Silence" by Pola Gojawiczynska, Warszawa, 1936

Heart, from the Cyclus Silesia, 1937

Heart, from the Cyclus Silesia, 1937

"Blackout, Will There Be War?", 1940

"Blackout, Will There Be War?", 1940

El Mole Rachmim, from the series "Screaming Stones", 1946

El Mole Rachmim, from the series "Screaming Stones", 1946

Sea Serpent or "European Army", 1954

Sea Serpent or "European Army", 1954

"Wlewnice" from the series "Black Silesia", 1937

"Wlewnice" from the series "Black Silesia", 1937

A biography on the artist's life can be found here.

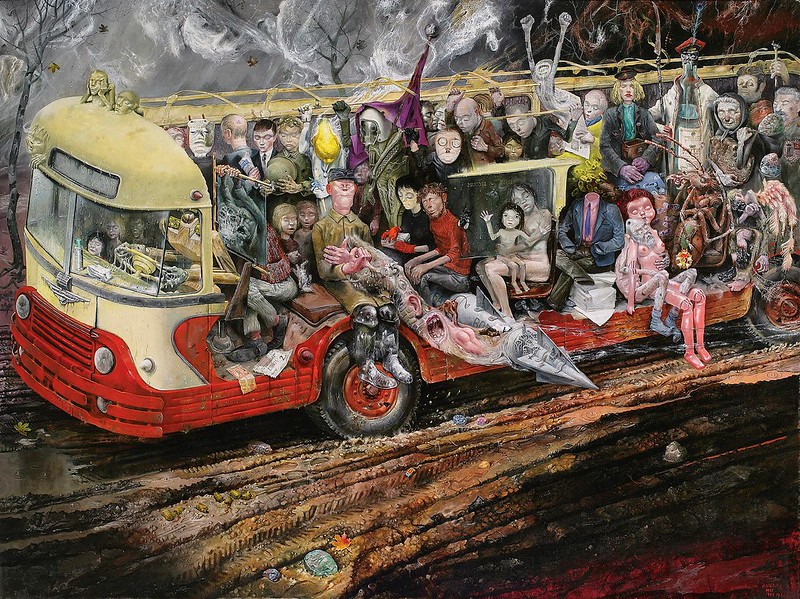

The Jewel in the Skull: ‘James Cawthorne: The Man and His Art’

Richard McKenna / September 17, 2020

James Cawthorn: The Man and His Art

James Cawthorn: The Man and His ArtBy Maureen Cawthorn Bell

Jayde Design Books, 2018

Stuff has to happen when it has to happen, I suppose. Back in the summer of 2018, I’d pre-ordered a copy of James Cawthorn: The Man and His Art, but by the time it was released, the family health issues that had been increasingly dominating my life over previous years had consumed it completely. When the book arrived, I didn’t even leaf through it; just unwrapped it and stuck it on a shelf, registering only that it weighed a ton and must be hundreds of pages long. And perhaps because of its association with a sad time, I completely forgot about its existence for a couple of years, only finally opening it the other night on a sudden impulse. Would what it contained be powerful enough to burn off any negative personal associations and also not be the kind of dismal self-congratulatory fannery that makes you want to chuck all your books away and start getting into metalworking or something? Well, yes it would—James Cawthorn: The Man and His Art is absolutely fucking mind-blowing.

Back in the ’70s and ’80s, Cawthorn was everywhere: the covers of his comic book adaptations of Michael Moorcock’s Elric stories were a fixture on the wall of every head shop, goth shop, comic shop, second-hand bookshop, and pawn shop I entered until I was in my mid-20s, and I’d grown up seeing his illustrations in things like New English Library’s Strange World of Science Fiction, the Savoy Books edition of Moorcock’s The Golden Barge, and the four kids’ sci-fi anthologies that Armada books put out in the 1970s. But, weirdly, it wasn’t until I sat down with this volume that I realized just how deeply his work saturates my own aesthetic life. Which is to say, my life. Not that I’m claiming my aesthetic or actual life are of two shits’ worth of interest to anyone except myself, of course, but it’s a strange feeling to suddenly realize that the blur that’s always been there at the edge of your attention is actually one of the spinning flywheels driving your mind—reminding you how many of those people existing on the margins of the culture remain marginal despite their contributions to shaping it. Cawthorn—who passed away in 2008—is a recognized figure among genre obsessives, but how did someone so interesting and idiosyncratic, who was once so ubiquitous, fall into such relative neglect?

Cawthorn was a child of the North East, an unfairly disregarded region of England, historically far from the money of London or Manchester, that has suffered massively since the Conservative government led by Margaret Thatcher set in motion the definitive closing down of the mines, heavy industry, and shipyards that had been the area’s backbone for centuries. As the final remnants of the steelworks and shipyards are gradually sold off to venture capitalists, that process of neglect is now pretty much complete, yet it’s a beautiful and magical place with its own strange magic, with deep links both to the ancient past and to the future—which makes sense, given how much of the future the locals dug, hammered, and welded together before they were sold out by the Tories. If you’re in any doubt about the North East’s futurist vocation, just remember that some of our culture’s most pervasive images of the future are the handiwork of another product of the region, one Ridley Scott, who certainly took inspiration from the vast petrochemical complexes lining local rivers (as anyone who ever flew into Teesside airport at night can testify). A self-taught, working-class illustrator, Cawthorn seems like a perfect reflection of that local genius, and in a way his relative anonymity mirrors that of his native land.

James Cawthorn: The Man and His Art contains (apparently—I didn’t count) something like 800 color and black and white illustrations that cover his entire career. The contrast between the scratchy detail and dense chiaroscuro of his b&w work and the vaguely lysergic glow of his color art highlight how the two exist as entirely distinct entities, which, however, complement and complete one another when seen together here. And his color work also inspires the thought that perhaps Cawthorn’s relative oblivion is partly due to his style being too outsider-ey, too delicate and lurid (in a good way) to work at its best in the medium that was most lucrative and that offered most visibility during the time he was working—the paperback cover.

In fact, one striking thing about Cawthorn’s work is that it always retains the beauty of the obsessive amateur, never feeling glib or by-the-numbers. Even in the drawings that look most rushed, you can feel the commitment animating each piece—the euphoric sensation of watching cheap felt-tip pens somehow create entire new worlds. And unlike many other artists, Cawthorn’s aesthetic becomes more, not less, compelling and intense the more of it you see, as he endlessly mines and refines the mineral splendors of his own imagination in pursuit of his totally individual aesthetic. Looking through the book, it rapidly becomes clear that Cawthorn’s best-known images—to those who know them—aren’t even his most striking. In fact, it’s difficult to illustrate this review properly because some of his most memorable work doesn’t exist even in the daunting repository of everything that is the internet, and I don’t want to bugger up the spine on my copy.

The book has clearly been a labor of love for Cawthorn’s sister Maureen and publisher John Davey, and Maureen’s evocative and delicate memoir of him casts a lot of light on the personality behind the portfolio of artwork. Alan Moore and Michael Moorcock (a close friend of Cawthorn from his youth until Cawthorn’s death) both provide genuinely touching contributions, and the ever-reliable John Coulthart does a lovely job of arranging and presenting everything in a way that makes sense of the ridiculous amount of material, which ranges from the comics Cawthorn drew at school to the lovely t-shirts and birthday cards he produced in mind-boggling numbers for family and friends.

So like I said, James Cawthorn: The Man and His Art is absolutely fucking mind-blowing, a reminder of the violently surreal and inspiring power that imagery of this kind can possess when emptied of retrogressive cliché and self-satisfied rhetoric and filtered through a distinctive talent. It’s a potent inducement to pick up a pen, or a pencil, or a keyboard, or just anything, and put your imagination into use.

![]() Richard McKenna grew up in the visionary utopia of 1970s South Yorkshire and now ekes out a living among the crumbling ruins of Rome, from whence he dreams of being rescued by the Terran Trade Authority.

Richard McKenna grew up in the visionary utopia of 1970s South Yorkshire and now ekes out a living among the crumbling ruins of Rome, from whence he dreams of being rescued by the Terran Trade Authority.

Portals and Presences: The Surreal Landscapes of Hipgnosis

Michael Grasso / September 16, 2020

Vinyl . Album . Cover . Art: The Complete Hipgnosis Catalogue

Vinyl . Album . Cover . Art: The Complete Hipgnosis CatalogueBy Aubrey Powell

Thames & Hudson, 2017

There’s always a danger of excessively romanticizing the era of the vinyl LP. Issues of sonic fidelity and durability aside, though, there’s one aspect of records on 12-inch wax that seemingly everyone does miss, and that’s the full-size record cover. Album covers during the heyday of psychedelic rock and roll were gateways to other worlds, their art often the province of esteemed painters and illustrators, their cryptic surrealism often filled with esoteric codes and symbols. Probably no other artistic collective was more famous during this decadent era than the London partnership known as Hipgnosis. From its edenic origins palling around with the rising stars of the late-’60s London psychedelic underground through to its mature period making iconic platinum album covers for global sensations like Pink Floyd, Paul McCartney, and Led Zeppelin, the creative forces behind Hipgnosis gained a rightful reputation as artistic visionaries whose work didn’t merely create identifiable brands and images for a musical group. Hipgnosis covers added to the mystique of the music, creating a visual component that rendered itself an indelible part of the listening experience.

“Album covers… defined you,” says Hipgnosis founder Aubrey “Po” Powell in his “Welcome to Hipgnosis” history in 2017’s Vinyl . Album . Cover . Art: The Complete Hipgnosis Catalogue, a 300 plus page full-color hardcover monster that reproduces the collective’s entire album cover output from 1967 to 1984. “The covers gave an inkling of your personality, your musical tastes and preferences, and just how up to date and hip you were.” Powell, Hipgnosis’s photographer, met his creative partner Storm Thorgerson at a hashish-suffused party across the street from his rooming house (that was suddenly raided by the police) attended by much of Pink Floyd. In that afternoon, a bond was formed between Powell and Thorgerson, a graduate student in film at the Royal College of Art. In these swinging, soon-to-turn-psychedelic times, Thorgerson and Powell were at the center of a music and art scene that would break out of the cozy confines of a few odd students and onto the global stage. Named after a piece of graffiti that Floyd’s Syd Barrett scrawled on the door to their apartment in pen, Thorgerson and Powell’s partnership (Throbbing Gristle member Peter “Sleazy” Christopherson would join in the mid-1970s) created some of the most memorable album covers of the era.

Hipgnosis’s first rock client was Pink Floyd: seen here are three of their Floyd covers: the Dr. Strange-meets-real-life-alchemy of 1968’s A Saucerful of Secrets, the recursive design of 1969’s double album Ummagumma, and the iconic 1973 cover for The Dark Side of the Moon.

Vinyl . Album . Cover . Art . itself is equal parts fond (post-)hippie memoir and hard-nosed realistic account of what it was like to run a business in the often high pressure, big-money business of 1970s rock ‘n’ roll. The book contains a brief—if frank and fascinating—foreword from Peter Gabriel, who worked with Hipgnosis while leading Genesis and for his first three solo album covers. Throughout the hundreds of album covers, Powell provides a wry and informative running commentary on the personalities, problems, and sudden moments of inspiration—provided by both musicians and the cultural and natural environment—that contributed to Hipgnosis’s success. The Surrealist movement of the 1920s and specifically photographer Man Ray get quite a few name-drops in Powell’s assessment of the Hipgnosis catalog, and it’s easy to see why. The nude human form, out-of-place manmade objects juxtaposed with the organic, obvious, and often unnatural-looking photo collage: all of these definitive Surrealist techniques appear with frequency in Hipgnosis’s early output.

Much of the overall aesthetic of psychedelic rock took its inspiration from long-past artistic movements with Romantic, back-to-nature overtones: Art Nouveau and Arts and Crafts, notably. With the surrealist edge of Hipgnosis’s designs, however, a flash of danger and alien weirdness was added to rock’s visual lexicon. Hipgnosis’s efforts at whimsical storybook-style covers for the Hollies and Genesis stick out like sore thumbs: solid efforts, but very much against the subversive grain of most of their work at the time. The covers where Hipgnosis unites Victorian twee with counterculture edge—such as using century-old techniques to hand-tint pastel color on Powell’s contemporary photos—do provide a pleasing synthesis of old and new.

Gentle nostalgic folkie Al Stewart’s understated style might not seem like it jibes with the fantastic scenes conjured on Past, Present and Future (1973) and Time Passages (1978). On the other hand, Dark Side of the Moon producer-turned-bandleader Alan Parsons’s 1978 album Pyramid was directly influenced by Parsons being “preoccupied with the Great Pyramid of Giza,” to the point of “obsession” and “out-of-body experience.”

But it’s not just the art movements of the past that provided Hipgnosis with ambient inspiration. The counterculture’s well-attested conscious fusion of old and new, of the esoteric with contemporary pop and outsider culture, including science fiction and comic books, is on display throughout the Hipgnosis corpus. One of their very first commissions, Pink Floyd’s 1968 A Saucerful of Secrets, very obviously embodies this fusion, with its mixture of images from “Marvel comics and alchemical books.” Powell and Thorgerson attest to their being “avid followers of Stan Lee… Steve Ditko and Jack Kirby,” all while recognizing that “in those heady days of 1968—a man was soon to land on the Moon, alchemy was a hot topic, extraterrestrials were a certainty, Tarot readings and throwing the I Ching were de rigueur—the search for enlightenment in the East was a definite must.”

Whichever way the cultural winds were blowing, Thorgerson and Powell always forged a link to the music in their designs. Even in cases where the imagery looks too mystically epic or weird for the music on the disk, such as the covers for Scottish folk musician Al Stewart’s Past, Present, and Future (1973) and Time Passages (1978), the music’s overall themes—remembrance, nostalgia, prophecy, and folk memory—contain a tenuous throughline justifying figures leaping through strange mystic portals or tuning into a radio station that glitches out all of reality. All these strains of the magical and surreal, from Renaissance alchemists to haunted Victorian portraitists to avant-garde plumbers of the post-World War I collective unconscious to Dr. Strange and the Silver Surfer—Hipgnosis synthesized these with the subconscious themes of the music to create visions that defied reality. Powell’s photographic eye and Thorgerson’s dreamlike visions found common cause in composing images that looked like set pieces on strange alien worlds or in magical faerie realms. But even with all the photographic trickery and post-production flourishes available to them as they moved out of student darkrooms and into their own studio, Hipgnosis still found inspiration out there on our Earth’s weirdest real-life spots. From the Giant’s Causeway in Ireland to a cracked, dry Tees estuary in the North of England to deserts in North Africa and the American West, Hipgnosis’s most memorable landscapes are worlds where something has gone awry, where weird monuments, alien beings, and strange hauntings abound.

Hipgnosis had a knack for using unique real-world backdrops to create eerie scenes for their album covers. Italian rock progressivo group Uno’s self-titled 1974 album depicts a mysterious hieratic harlequin with a glowing geodesic dome for a brain emulating the pose of the famous English chalk figure, the Long Man of Wilmington.

Of course there are the usual stories of rock star excess in the book, with the personnel from Hipgnosis being flown all across the world for photo shoots and consultations with the biggest names in ’70s corporate rock. In many cases, the musicians and managers themselves couldn’t resist being part of the process. Paul McCartney enjoyed hamming it up on the cover of Band on the Run, and a few years later Macca wanted to be the one to personally place the giant letters on a London theater marquee for the cover of Wings At The Speed Of Sound. Noted hard case Peter Grant, the imposing manager of Led Zeppelin, was giddy—he “burbled with glee,” according to Powell—over Hipgnosis’s proposal for a worldwide scavenger hunt of a thousand replicas of the eerie totem from the cover of 1976’s Presence. One could argue that Hipgnosis, Led Zeppelin, and Peter Grant invented the music industry alternate-reality game in 1976 (sadly, the surprise Presence publicity stunt never got off the ground after it was leaked by the music trades).

Powell is honest throughout the book about the various misfires; he finds some of their ideas in ridiculously poor taste upon reassessment and most modern observers would be hard-pressed to disagree. The collective’s pinpoint arch visual humor certainly sometimes misses the mark. If I were to sum it up: the Hipgnosis catalog contains a few dozen stone-cold classics, a bunch of forgettable designs, and a few that look like rejects for Spinal Tap’s album Shark Sandwich. Hipgnosis’s wit was used to best effect when channeling those common cultural currents mentioned above: for example, 10cc’s classic cover for their album Deceptive Bends—the creation of which is broken down in great detail by the late Thorgersen in a contemporary piece from 1977 included in the book—talks about the physical and logistical challenges in place from the beginning but also places the imagery of the diver carrying the helpless damsel in its proper context with “monster” B-movies like Creature From the Black Lagoon (1954) and Robot Monster (1953). Trawling our collective pop culture unconscious, Hipgnosis called forth all kinds of creatures from the deep over their less than two decades on Earth, creatures that walk amongst us long after the collective’s demise.

![]() Michael Grasso is a Senior Editor at We Are the Mutants. He is a Bostonian, a museum professional, and a podcaster. Follow him on Twitter at @MutantsMichael.

Michael Grasso is a Senior Editor at We Are the Mutants. He is a Bostonian, a museum professional, and a podcaster. Follow him on Twitter at @MutantsMichael.

Feliks Jabłczyński - Mephisto, 1893

A Coke and a Smile: Tsunehisa Kimura’s ‘Americanism’

Exhibit / September 15, 2020

Americanism, 1982

Object Name: Americanism

Maker and Year: Tsunehisa Kimura, 1982

Object Type: Photomontage

Description: (K.E. Roberts)

Unlike his younger compatriots Shusei Nagaoka, Hajime Sorayama, Eizin Suzuki, and Hiroshi Nagai, who broke into the American illustration market with glistening airbrushed futures and breezy, pastel-colored beach scenes, Tsunehisa Kimura’s output was absurd, darkly surreal, and often apocalyptic. He remembered the devastation wrought by the war, and aimed his photomontage squarely at imperialism, colonialism, and, during the 1980s, a locked-and-loaded America whose leaders were playing an increasingly dangerous game that might have enveloped the entire globe.

Kimura’s most recognized piece is probably Waterfall, circa 1979, which shows Manhattan beset by, or rather integrated with, Niagara Falls. The scene evokes disaster, but there’s something serene about it too—the riotous natural world and the built environment appear to commune, as is the goal in traditional Japanese architecture; not so in America, where we build things to keep nature—including other people—out. New York is frequently Kimura’s muse: New York encased in crackling ice; New York encased in fire at the end of the world (or is it the violent beginning of the world?); an ocean liner (is it the Titanic?) stands in for the Hindenburg, running aground on the Empire State Building.

There’s nothing serene about Kimura’s cover to the 1984 Midnight Oil LP Red Sails in the Sunset, either, showing a bombed-out, scorched-earth Sydney. A simmering red sun settles in the dust, similar to the black sun that precedes the atomic explosion in Katsuhiro Otomo’s Akira (1982-1990). And his cover for Space Circus’s Fantastic Arrival (1979), where American astronauts caper about on the Moon—while on fire—is similarly uncomfortable. Waterfall, in various edits, has also appeared on several LP covers.

Americanism is a pointed critique of both WWII-era (the photos are from the ’40s) and ’80s America, consumed with consuming and not much else, though the world (including Hiroshima and Nagasaki) may burn. The ironic nonchalance of the juxtaposition is, once again, striking. The Statue of Liberty is drowned (a long-standing visual motif in sci-fi) in a 1977 photo, and an untitled piece from 1984 shows the noble lady once again, this time hurtling over (or towards) the New York skyline under the power of six American ICBMs—which huddle beneath her skirts!

Kimura’s work was collected in 1979’s appropriately title Visual Scandals by Photomontage, as far as I know the only such collection published in the US.

“God Likes Winners”: Catharsis and Community in 1970s Disaster Movies

Features / August 28, 2020

ROBERTS: I started watching (mostly rewatching) disaster movies old and new about a week into lockdown, which I suppose makes perfect sense. The genre turns on spectacle and catharsis, but it also pacifies: no matter how bad the real world gets, it could always get worse—so be grateful that it’s not worse. But make no mistake: Irwin Allen and co. make perfectly clear that bad stuff is on the way, always, and we have to be prepared to persevere. “Shit happens” is embedded in our national lexicon. Take your lumps. Deal with it. Just do it. Be a leader, not a follower. It is all so bedrock America that I hardly care if it’s bullshit anymore—bullshit precisely because it’s allowed to be true. We live in a land where where there are only winners and losers: those who can buy their way out of catastrophes—catastrophes that are often preventable or mitigable but made inevitable by systemic bondage to profiteers, by explicit repudiation of the idea of community—and those who can’t.

It occurred to me last week, as I rewatched The Poseidon Adventure for the umpteenth time—inarguably the peak (heh) of the genre—that it is a representative piece of American mythology, as indispensable in its way as Red River or The Big Sleep or Easy Rider. “Hell, upside down,” the theatrical poster gushes. “Life is up there,” says the Luciferian Reverend Scott to resigned Belle Rosen, as if in response. “And life always matters. Very much.” It is the Dantean journey that gives the film so much gravitas, but the (dis)honorable Reverend, in his pre-catastrophe sermon, channels the Duke, not the poet:

So what resolution should we make for the new year? Resolve to let God know that you have the guts and the will to do it alone. Resolve to fight for yourselves, and for others, for those you love. And that part of God within you will be fighting with you all the way.

This ain’t the RMS Titanic, in other words. Americans don’t play show tunes as the ship goes down. No. We clamber up enormous, tasteless fake Christmas trees, traipse through fire and corpses, and swim through flooded engine rooms to get to the cast iron hull, just as the improbable rescue team (never give up, never surrender!) is set to blowtorch a three foot square passage to sunshine-y safety.

MCKENNA: I have vague memories of watching The Poseidon Adventure for the first time in its debut showing on British television over the 1979 Christmas holidays, and it felt like I was being initiated into a new understanding of the way the world worked. Back then, the UK was a very different place—stoic certainly, but a lot less given to mors tua vita mea walk-it-off lead-don’t-follow bullishness than our increasing alignment with you lot over the last few decades has made us. Plus it was—for the most part—relatively safe and stable-seeming. So the lesson I took from The Poseidon Adventure, call it the Irwin Allen Doctrine if you will, was that stability is fragile and that in any moment, reality can be turned upside down (bum-tish!). The takeaway of my child-of-’70s Britain brain was not the perhaps more logical “be brave, fight on, struggle through” preppery conclusion, but a kind of anxious resignation to disaster that, after the many disaster movies I would see over the following years, would be taken to its logical extreme in 1984 with the BBC’s nuclear war disaster movie Threads. Weird how the same stimulus can provoke such different reactions when the context is different.

Watching it now for the first time in decades, I’m struck by several things. Firstly and most superficially, Roddy McDowell’s atrocious Scottish (if it is even supposed to be Scottish) accent, and the awe-inspiring shittiness of the model work that opens the film, which looks appalling on a telly, so it’s inconceivable that on a cinema screen it didn’t provoke howls of outrage. I’m also struck by how great Pamela Sue Martin and Stella Stevens and Ernie Borgnine (as Linda and Mike Rogo) are (predictably, it’s Borgnine who pulls out the one moment of genuine pathos in the whole film), and by how much I’ve missed Shelley Winters. But mainly I’m struck by what a dick the Rev. Scott is. Sure, he gets his little gang of followers—well, some of them—up to the propeller shafts, but seemingly as much by luck as by any actual plan or talent above and beyond not giving up. How many other little groups of survivors led by some other manic Hackman convinced he knows the way are trying to do the same thing and don’t make it? The film makes it easy for itself by following the only one that does (we know it’s the only one because the rescue helicopter pisses off as soon as they’ve emerged), but the whole thing feels like we’re watching someone—the Reverend Scott—grandstand their way through their issues with their own feelings of impotence and frustrated. I suppose it’s kind of in the cards that this is the case, though, given the way Scott tells the congregation at the sermon Kelly mentions above that “God likes winners.” I mean, it’s not like I’m much of a Bible student, but God likes winners? I thought he was planning on giving the planet to the meek?

Perhaps the whole thing is implicitly seen from a winner-loving God’s-eye POV, keeping the focus on the people that God likes so much while the losers all get smashed to bits. What do you think, Mike? Does that feel like something that was echoing through these films, until Threads proposed a disaster in which surviving was actually worse than dying?

GRASSO: For me personally, 1970s disaster movies have more often been something to analyze rather than enjoy; they do speak so clearly to a certain high American imperial bloat: bigger casts, bigger spectacles, longer running times, bigger publicity campaigns, cheesier gimmicks. So I think that’s why, when re-watching the arguable Big Three for this piece—the original Airport (1970), The Poseidon Adventure (1972), and The Towering Inferno (1974)—I was a little shocked to remember how downright boring all three of them are. Nothing specifically against the star-studded (and undeniably talented) casts, but so many of the actors seem to be content to hit their marks and pick up a paycheck. With the exception of standouts like George Kennedy in the Airport series (who goes from salt of the earth mechanic in Airport ’70 to “largely in on the joke” full airliner captain by the time The Concorde… Airport ’79 staggers across the finish line), or the unbeatable (yet somehow still slightly disappointing!) ¿quién es más macho? duo of Paul Newman and Steve McQueen in Inferno and the always, er, compelling Shelley Winters in The Poseidon Adventure. These big Hollywood names, a good number of them washed up and forgotten at the time, just look slightly on the side of mortified that their careers have brought them to this. But again, as you guys mentioned, these movies were also the biggest box office hits of their day, the star-studded, effects-laden blockbusters that ruled the cinemas and drive-ins before the coming of Star Wars. What gives?

I could trot out the usual rigmarole about these films speaking to a Nixon-era sense of American decline, of watching the technological wonders we’d built during the Cold War begin to decay and fall apart—and don’t get me wrong, that’s a really solid analysis! But I think there’s more to the ’70s disaster film than just a deeply buried sense of American masochism. Because there is that Rev. Scott-inspired sense of “we’re going to beat this thing with good old American know-how and good old American aggression” threaded throughout all these movies. Whatever else has been said ad infinitum about the supposed malaise of the 1970s, we know now, a half-century later, that most Americans literally never had it better economically than when these movies came out. And I think on some level, the writers and producers knew that. They knew that living in American society as a patriotic white American male between 1970 and 1975 was easy—possibly the easiest it had ever been, despite the dual prongs of Vietnam and Watergate—and that Americans on some level can’t abide the living being easy. The restless American needs conflict, he needs adversity, he needs a sinking ship or a burning building or a sudden earthquake to fight against to really prove we’re winners.

There is one thematic element of the early genre that is worth praising from a political perspective, though, and that’s the multi-level plots and the innocent bystander characters who get to prove themselves and their mettle during the disaster. Every B-level star or Golden Age of Hollywood re-tread gets a juicy character development scene or a subplot, and while, yes, the stars are the stars and the heroes are the heroes, in each one of these movies there are plenty of Just Plain Ordinary Folks among the square-jawed heroes. Maybe it’s not socialist realism or Brechtian dramatic deconstruction, but it’s the closest that the American blockbuster can bring itself to provide: a relatable, identifiable proxy for the ordinary schlub or harried housewife in the audience. It’s small “d” democratic in the best tradition of American literature and drama, and I unabashedly love it as a trope, whether it’s the aforementioned unexpectedly heroic Winters in Poseidon or Geneviève Bujold in Earthquake or countless other examples, ordinary doughty folks (including plenty of women!) get to save lives and be heroes. That seems like a fine and necessary moral and political lesson to come out of these things.

ROBERTS: I think these films are democratic in more ways than one. In The Towering Inferno, it’s the greedy developer who refuses to evacuate the building because he has a big deal at stake; in The Poseidon Adventure, the owner’s agent orders the Captain to push on at full speed to save money, rendering the ship unballasted; in Earthquake, architect Stewart Graff puts his firm in jeopardy by demanding a prize client pay for necessary safety measures in his new office building; in Twister, the bad guys in their shiny black vans are “in it for the money, not the science”; in Dante’s Peak, the town’s business leaders don’t want to evacuate because they’ll forfeit the windfall of the annual Pioneer Days Festival (just as the Mayor in Jaws refuses to close the beach during the summer tourism peak). Is this sounding familiar? Anyway, the list goes on. In the 2000s and beyond, climate change is often the culprit (with all the histrionics of an Aaron Sorkin script), and once again greed is at the core (heh) of the resulting cataclysm. Life may matter “very much” to Reverend Scott, but his country (and God, apparently) routinely sacrifices it so that the rich can stay rich.

These films also display and require shared sacrifice, often on a global scale—an unthinkable suggestion in America since at least the Vietnam War (bone spurs, anyone?). The rich can’t buy their way out of a burning (The Day the Earth Caught Fire) or freezing (The Day After Tomorrow) planet, though sometimes we have a distinctly undemocratic “ark” situation (When Worlds Collide, Deep Impact, 2012—yes, I watched it!), where the elite or “chosen” few get the chance to start a newer, better world. I think that’s why Richard has a different reaction to these films: Brits had no choice but to share the devastation and deprivation of World War II, among other tragedies.

The phrase “washed up” (heh) got me thinking as well. Not just in terms of the past-prime-time actors, who give the audience a sense of stability and hope as the cinematic destruction unfolds, but in terms of the country itself, as Mike alludes to above. As Rambo and his ilk fought and won Vietnam retroactively in the ‘80s, so the disaster films of the ‘70s gave us an enemy that was worthy of us, an enemy we could bear losing to, an enemy that could not be sympathized with—and at the same time an enemy we could claim a moral victory against.

MCKENNA: That’s a thought that struck me too, Kelly—how differently these films must have played in the States to the way they did everywhere else, even somewhere as nominally similar (as in, not at the time actually that similar at all) as the UK. Obviously a lot of the same mechanisms would have been at play, but it seems to me that—apart from the emphasis on thrills and catharsis—the focus over our way at least was perhaps more on the “disaster” part than the “movie”: on the implicit warning against hubris that set the superstitious protestant wiring buried beneath the country’s modernizing surface humming.

But then, only America could have afforded to make this kind of thing as a throwaway entertainment anyway: even second-tier Irwin Allen-ery would have been beyond the coffers of our national film industry, and presumably most others too. Only the US could assemble the means necessary to create mass acts of propitious magic showing the nation’s chutzpah win out over bees or bigfoot.

It’s no coincidence that the disaster movie came of age in a period of history when popular culture in all its forms was beginning to accept that the Earth was not simply an endless source of resources for us to to burn or melt down into aftershave bottles, and that if we kept hacking away at it, it might start hacking back. That schism in belief feels like it’s seeped deep into the bedrock of the zeitgeist since then, and the disaster movies of the decades that followed the ’70s have reflected that shift away from the surface. I’ve watched 2012 too, and, like so many of the modern disaster movies I’ve seen, it’s profoundly unsatisfying. For all that the special effects and stunts of the originals were considered epic at the time, there’s a staginess to the classic disaster movies that I think is an intrinsic element of their power (which makes me wonder about the parallels between the American disaster movie and the British tradition of pantomime, where marginal celebs and not-quite-has-beens are brought out around Christmas time to camp up old tales). A truly realistic disaster movie doesn’t quite hit the mark—the staginess, perhaps like the model ship in The Poseidon Adventure, is an essential part of the package, as is the weird bus-tour melange of character actors and stars. Those TV Guide-of-yesteryear casts you point out, Mike—they’re comforting. An American extrapolation of Brian Aldiss’s “cosy catastrophe,” which, like Kelly says, amps up the nation’s psychological needs.

GRASSO: As far as more contemporary disaster movies go, documentarian Adam Curtis had a stunning bit at the center of his most recent film, HyperNormalisation, where he presents a series of scenes from ’80s and ’90s disaster movies featuring titanic explosions (replete with crowds looking up at them in stunned awe) that seemed to spookily and accurately predict the traumatic images of destruction we all remember from September 11. Alien invasions, climate change-driven tidal waves, asteroids and eruptions from the Earth’s core—all these apolitical disasters fed into a spectacular idea of what our collective societal rupture point might look like. And then, suddenly, it all became real. This sort of special effects spectacle was echoed in the city-destroying pillars of light in the post-9/11 superhero film. Of course, with the 2000s superhero film, the “good guys” now have their own superhumans, wealthy tycoons, or secretive military organizations sporting a team of emotionally-stunted misfit recruits to fight against the city-destroying bad guys. The ordinary schlub from the 1970s is now nothing more than a bystander with no agency and certainly no impact.

The 1970s disaster flicks are necessarily smaller-scale, in both spectacle and stakes. I think back to how I first saw many of these films produced in the decade of my birth. Most of the time, it was either a lazy weekend afternoon movie on UHF television or a similar filler on cable superstations. Those are also the venues where I saw the more laughable disaster flicks, ones where the casts are closer to C-list than B-list. Two of the lesser-known ’70s disaster movies that are near and dear to my heart—made-for-TV Airport ripoff SST: Death Flight from 1977 and the Canadian City on Fire from 1979—featured on Mystery Science Theater 3000‘s pre-cable season on Minneapolis UHF station KTMA-23 and were standard parts of many UHF station’s syndicated film packages. As the ’70s went on, the disaster movie held on by its fingernails, reusing the same tired tropes and plot beats until 1980 came along and America decided it was time to laugh at all those tired tropes in the classic comedy Airplane! (whose plot points and even lines of dialogue were lifted, sometimes verbatim, from Arthur Hailey’s 1957 screenplay Zero Hour!). I think about David Zucker’s subsequent transformation into conservative “satirist” and a few elements of the original Airplane! that stick in my mind, like the titular airliner’s destruction of a Chicago (!!!) radio station “where disco lives forever,” and wonder if Zucker-Abrahams-Zucker’s repudiation of the ’70s disaster film was a harbinger of Reaganite reaction. But then again, I probably think that about most cultural events from 1980.

Most of all, I miss that very cosy catastrophe nature of these films, and Richard, you’re spot on: I think the ’70s disaster film is the American version of those very British Cold War apocalypses. When I see people on screen I recognize from classic black-and-white movies or from then-contemporary sitcoms and game shows, I feel on some basic level like everything is going to be all right. As the disaster film evolved in the ’90s and beyond, my comfort as a viewer was not a concern: all that mattered was overwhelming the viewer’s senses with physical destruction and dislocation, or having spandexed übermenschen militaristically fight against the destruction (which often had the effect of fomenting yet more mega-destruction). Glaringly mortal Shelley Winters isn’t coming to swim through the chaos and save us anymore. Make room for Tony Stark and Bruce Wayne.

ROBERTS: Here are two more idiomatic entries for you: God helps those who help themselves, and every man for himself. Both come deep from the well of Western culture (Greek tragedy and Chaucer, respectively), and both were codified in American Puritanism. For the Puritans, you never knew if you were saved or not until you woke up in Heaven (or “Hell, upside down”), so you simply exerted “a systematic self-control which at every moment stands before the inexorable alternative, chosen or damned.” And of course they were obsessed with the Book of Revelation, the foretelling of the disaster to end all disasters. Basically, they were not a lot of fun.

Do you remember the Pastor in 1953’s The War of the Worlds, an early sci-fi entry that’s also a proto-disaster film? He thinks he can make peace with the invading Martians, and slowly walks up to their hovering war machines, clutching his Bible and quoting the Lord’s Prayer. He’s immediately blasted into ashes. And yet, at the very end of the film, the protagonists are reunited in a church filled with silently praying refugees, and as the Martians begin to attack the Lord’s House, they start to drop dead. You just never know which God you’re going to get.

In one of my favorite scenes in The Poseidon Adventure, Scott and his flock are shocked to come across another, even more bedraggled, group of survivors. They file past in a line, heads down, resigned, plodding. The leader, a doctor, explains that they’re headed towards the bow, which Scott explains is underwater. They are the damned, just like the survivors who refused to climb up the giant Christmas tree. And Scott represents both faith and reason. In the end, God pisses on him too—a punishment for the prideful, mortal perseverance that got him to the finish line.

As you’ve both said, these narratives have become a glut and blur of superheroes and CGI. I guess they were never very much more. Disasters befall us in disaster movies because we’re fallen, because we fuck everything up and yet still have the nerve to believe we’re exceptional, “elect.” And they’re supposed to remind us that we’re part of a human community after all, something that real disasters do. Or did, I should say. That trust is gone. The appeal to reason is gone. God is a gun. It’s the war of each against each. We’re the disaster now.

Millennials are the Greatest Generation: Ira Levin’s ‘A Kiss Before Dying’

Noah Berlatsky / August 25, 2020

Tom Brokaw popularized the term “The Greatest Generation” in 1998 to describe the Americans—and especially the American men—who survived the Depression and fought against Nazism in World War II. Brokaw saw this cohort in valedictory, heroic terms.

Tom Brokaw popularized the term “The Greatest Generation” in 1998 to describe the Americans—and especially the American men—who survived the Depression and fought against Nazism in World War II. Brokaw saw this cohort in valedictory, heroic terms.

They answered the call to help save the world from the two most powerful and ruthless military machines ever assembled, instruments of conquest in the hands of fascist maniacs.

They faced great odds and a late start, but they did not protest. At a time in their lives when their days and nights should have been filled with innocent adventure, love, and the lessons of the workaday world, they were fighting, often hand to hand, in the most primitive conditions possible…

In line with this hagiographic blueprint, discussions of World War II veterans are mostly nostalgic and congratulatory. They saved the world for us. Of course, we all know they weren’t perfect (insert obligatory nod here to Jim Crow and Japanese internment camps). But we nevertheless owe them a debt of gratitude for their service and their sacrifice.

But did people at the time see the Greatest Generation as the greatest? Ira Levin’s first novel, 1953’s A Kiss Before Dying, suggests the answer is “not so much.” Levin, who was born in 1929, just too late to participate in World War II himself, presents the men who fought against Hitler much as later writers would present the men who fought in Vietnam. Rather than saviors preserving the nation, the “greatest generation” for Levin is subversive, unstable, and a danger to order and social verities. That characterization of the young gives the book a queasy, disorienting relevance, as if Levin confusedly thought he was writing twenty years later—or forty. Or seventy.

The novel’s main character is Bud Corliss, the good-looking, working-class son of an unsuccessful father and an over-indulgent mother. Corliss is drafted, fights in the Pacific in World War II, and is honorably discharged in 1947. He goes to college, determined to make his fortune by marrying a wealthy woman, and starts dating Dorothy Kingship, the daughter of industrialist Leo Kingship. When she becomes pregnant, however, he realizes that her father will disown her for immorality. He kills her by pushing her from the roof of the municipal building where he has lured her, ostensibly to be married. He successfully makes her death look like a suicide, and there is no police investigation.

Corliss then sets his sights on Dorothy’s older sister Ellen. Using information he obtained about her from Dorothy, he woos her and becomes her fiancé also. She becomes suspicious of the cause of Dorothy’s death, however, and when her investigation threatens to expose him, he kills her too. He turns to the third Kingship daughter, Marion, and she falls in love with him too. However, Gordon Grant, a DJ who met Ellen while she was investigating Corliss, uncovers his plotting and warns Leo and Marion. They confront Corliss in Leo’s factory, where they semi-accidentally force him to fall into a vat of molten copper.

Corliss is a veteran, but he is not portrayed as a paragon. On the contrary, he’s lazy and vain, and these qualities are highlighted, or exacerbated, by the G.I. Bill. He drifts from acting school to Stoddard University, “which was supposed to be something of a country club for the children of the Midwestern wealthy,” his tuition guaranteed by the government.

The war, and social programs for veterans, allow the lower classes to mingle with their betters, resulting in boastful ambition and sociopathic violence. Corliss is evil in part because of his burning sense of entitlement beyond his station, an ambition nourished by the social dislocations of war and welfare. While he’s fighting abroad, his father conveniently dies in an auto accident, symbolizing the son’s emancipation from his past class status and the old hierarchies. Society and family alike are shattered and upended, freeing him to go down “the road to the success he was certain awaited him.”

The novel’s anxieties about Corliss’s class mobility are tangled up with concerns about gendered disorder. He pushes Dorothy to get an abortion (a plot point notably excised as too scandalous in the 1956 film adaptation), underlining the younger generation’s disdain for traditional family values. More, Bud himself is feminized—A Kiss Before Dying is a noir, and Corliss is cast in the seductive femme fatale role. He is fussy and meticulous about his appearance, and determined to advance through sexual wiles rather than hard work.

At Stoddard, as Bud starts dating Dorothy, he orders Kingship industrial pamphlets (“Technical Information on Kingship Copper”) and reads them with devoted intensity, “a musing smile on his lips, like a woman with a love letter.” When he romances Dorothy, and Ellen, and Marion in turn, he is really courting Leo Kingship, the patriarch. Leo’s daughters are merely convenient, interchangeable erotic pathways for Bud’s queer, singular passion. This is Eve Sedgwick’s “male homosocial desire,” in which men’s lust for other men and men’s lust for other men’s wealth and status are intertwined, displaced, and inseparable. Bud has one of his few honest, visceral emotional experiences towards the novel’s end, when he is being given a tour of the copper plant. He sees it as a “heart of American industry, drawing in bad blood, pumping out good! Standing so close to it, about to enter it, it was impossible not to share the surging of its power.” He is at once ravished and ravisher, entering into and filled with intoxicating patriarchal oomph.

Corliss also feels that pulse of eroticized dominance after each of his kills—and especially after his first murder, which takes place during the war. Corliss gets separated from his unit and stumbles upon a lone Japanese soldier, who tries to surrender to him. The enemy urinates in his pants in fear, and then Corliss shoots him, with a sensual deliberation.

Quite slowly, he squeezed the trigger. He did not move with the recoil. Insensate to the kick of the butt in his shoulder, he watched attentively as a black-red hole blossomed and swelled in the chest of the Jap. The little man slid clawing to the jungle floor. Bird screams were like a handful of colored cards thrown into the air.

After looking at the slain enemy for a minute or so, he turned and walked away. His step was as easy and certain as when he had crossed the stage of the auditorium after accepting his diploma.

The phallic gun, the yonic wound, and the orgasmic cries of the birds give way to a post-coital satisfaction more thorough than any pleasure Bud experiences in the arms of the Kingship daughters.

War awakens something in Corliss; he learns the pleasure of violence, which he carries back with him to unsuspecting and vulnerable civilians in the US. The dynamic is similar to David Morrell’s 1972 novel First Blood, in which veteran John Rambo unleashes a one-man Vietnam war on a sleepy American town. Rambo’s violence is notably racialized. Part of what happened to him in Vietnam is that he became infected with Southeast Asian methods and Southeast Asian anti-Americanism; fighting the non-white enemy turned him into the non-white enemy. Corliss, too, becomes what he fought. In the moment before he is forced into the copper vat, he soils his pants, and he remembers the soldier he killed.

The front of his pants was dark with a spreading stain that ran in a series of island blotches down his right trouser leg. Oh God! The Jap…the Jap he had killed—that wretched, trembling, chattering, pants-wetting caricature of a man—was that him? Was that himself?

Corliss’s identity and that of the Japanese man are confused as victims, and therefore also as aggressors. The vision of the Japanese as pitiful cowards substitutes for, but does not erase, the more prevalent image of the Japanese as implacable monstrous “fascist maniacs,” to use Brokaw’s term. Like Rambo, Bud as a soldier is stained with foreign violence. His assault on the status quo recapitulates the assault of a foreign enemy, and his death recapitulates that enemy’s defeat.

Levin, then, presents Corliss as an amalgamated threat, vaguely associated with a range of disparaged identities—young, working class, feminized, queer, non-white, non-American, veteran. This agglomeration of marginalized threats must be squashed by a perhaps overly strict but still essentially legitimate white, patriarchal order.

This familiar conflict is usually seen in pop culture through a generational lens. Levin’s portrayal of Bud foreshadows invidious stereotypes of lazy, feminized, racialized hippies and lazy, feminized, racialized millennials. But if even the youth of the Greatest Generation were smeared in this way, maybe the problem is not the kids themselves, but the conventional, persistently invidious stereotypes of rebellious youth. Every generation, even the greatest, is viewed as a potential betrayer, ready to overthrow the white male capitalist order. And so every generation, even the greatest, must be dumped into that copper vat, melted into the same mold, its old form erased and forgotten so the next generation’s demands can again be portrayed as novel, without history or legitimacy. The greatest generation is always the last generation. The young are supposed to kiss them before dying.

![]() Noah Berlatsky is the author of Wonder Woman: Bondage and Feminism in the Marston/Peter Comics.

Noah Berlatsky is the author of Wonder Woman: Bondage and Feminism in the Marston/Peter Comics.

George Ernest Studdy - Illustration from the publication “The Bystander”, Aug. 5, 1908

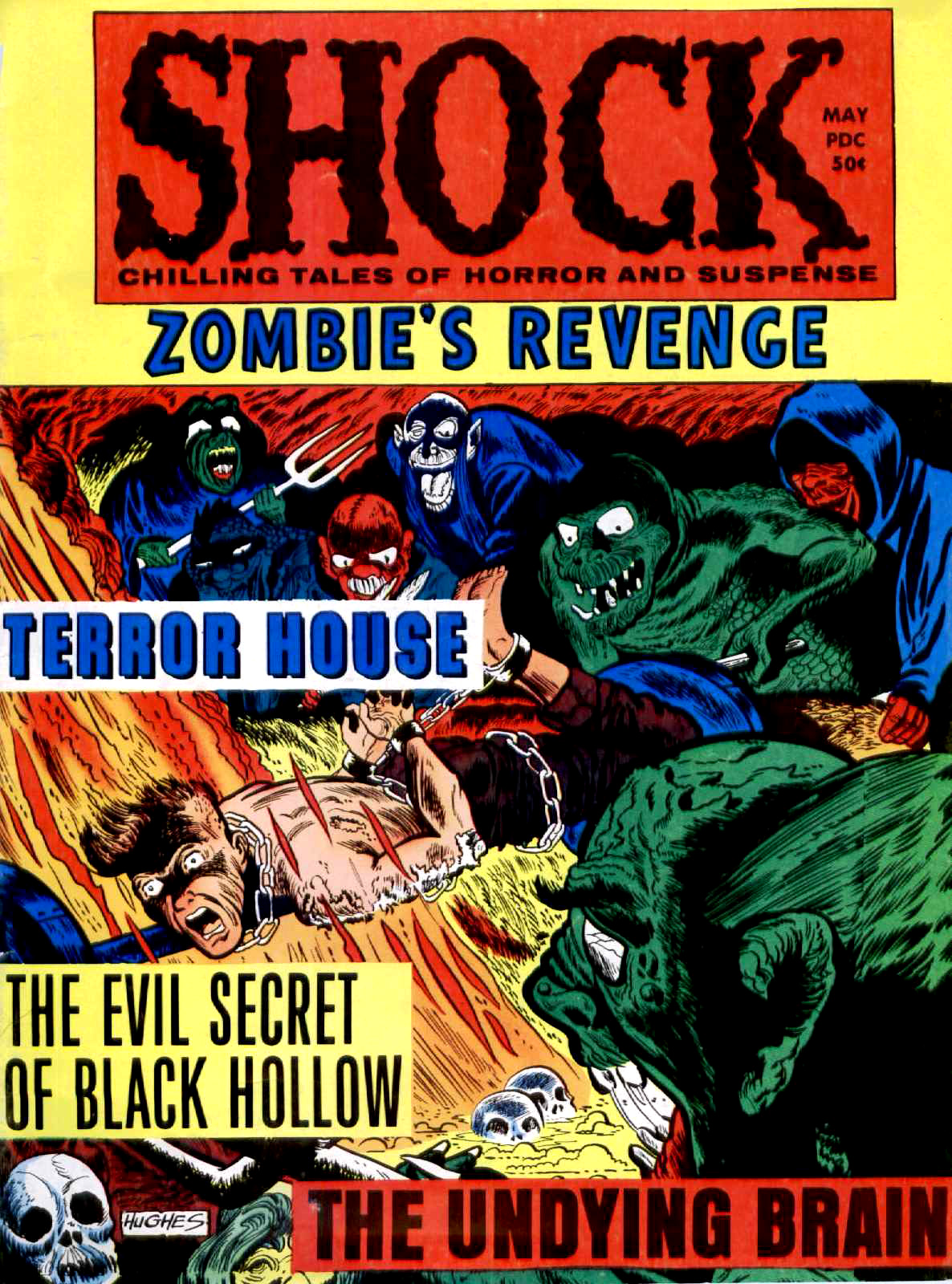

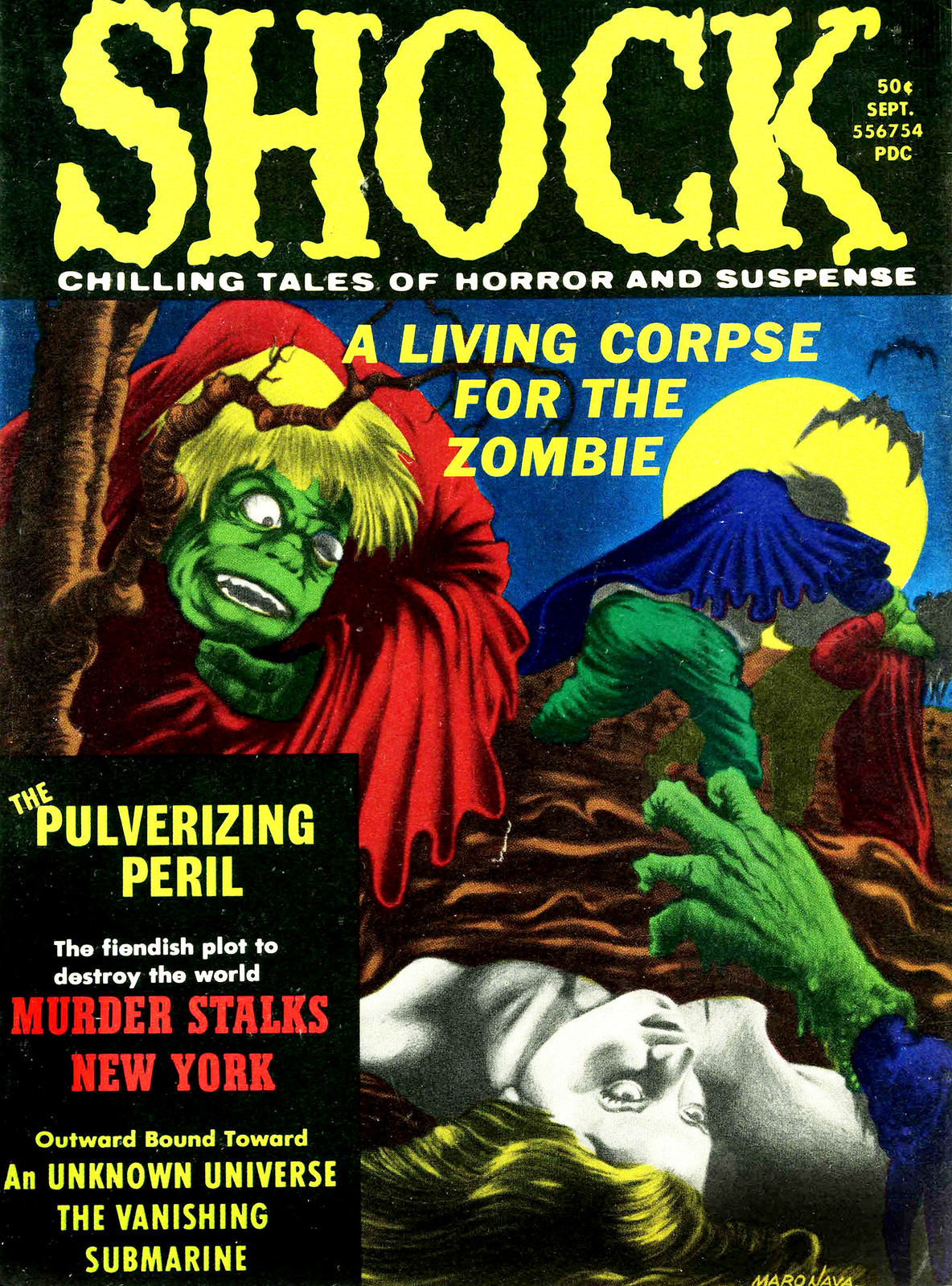

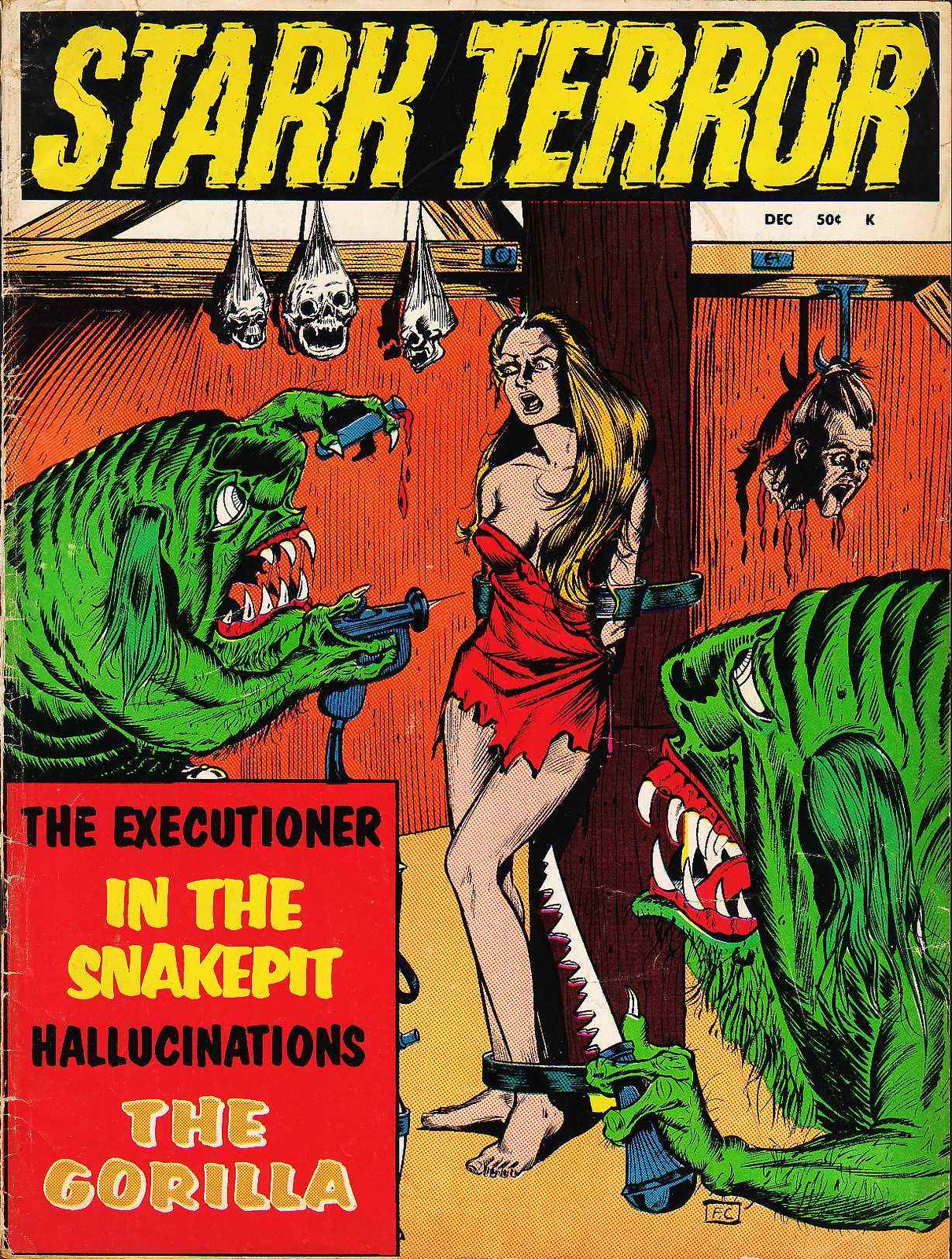

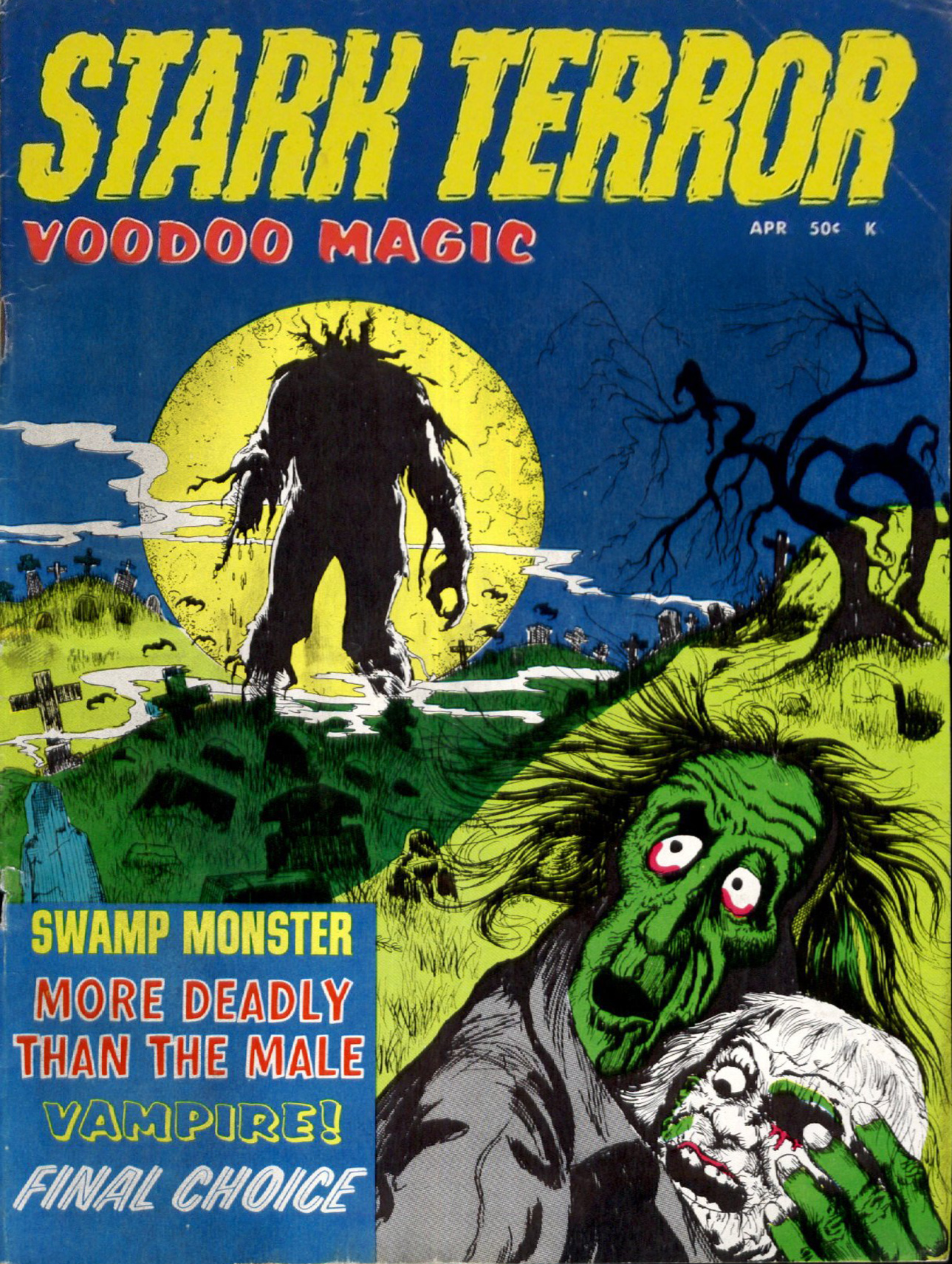

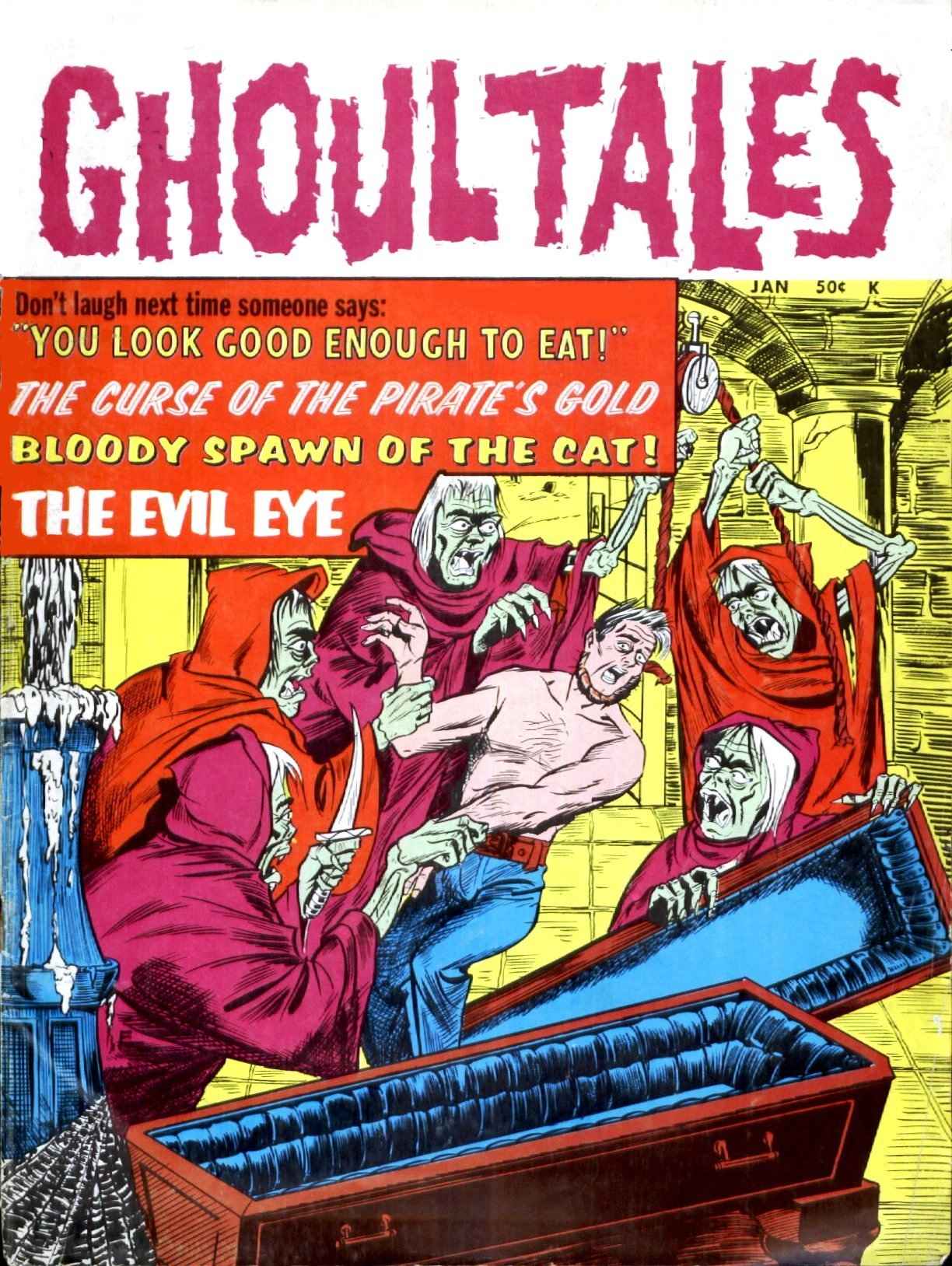

Shock Magazine Covers (1969 - 71) Stanley Publications

The Rot at the Root: Activism and Agency in ‘Captain Planet’ and ‘FernGully’

M.L. Schepps / August 6, 2020

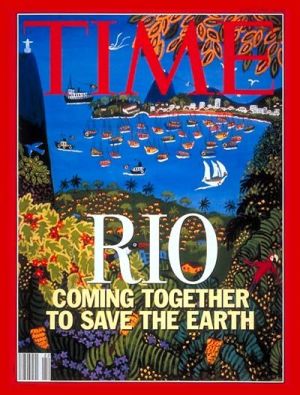

At the break of dawn upon the beach, a thousand representatives of the “Female Planet”—ranging from white-clad Canbomblé, damp in honor of the ocean goddess Yemoja, to realtors from Anchorage—raised mirrors to the pallid sky, seeking to reflect the light of their hope towards the sprawling Riocentro Convention Center that was the focus of the world’s attention. Amid a sense of urgency, representatives from 178 nations gathered for what was the largest United Nations conference in history. Activists, scientists, prominent entrepreneurs, entertainers, and world leaders alike urged unity and immediate action, while one representative of the youth environmental movement emphasized that “we’re all in this together.” The year was 1992, and the Earth Summit was underway in Rio de Janeiro.

At the break of dawn upon the beach, a thousand representatives of the “Female Planet”—ranging from white-clad Canbomblé, damp in honor of the ocean goddess Yemoja, to realtors from Anchorage—raised mirrors to the pallid sky, seeking to reflect the light of their hope towards the sprawling Riocentro Convention Center that was the focus of the world’s attention. Amid a sense of urgency, representatives from 178 nations gathered for what was the largest United Nations conference in history. Activists, scientists, prominent entrepreneurs, entertainers, and world leaders alike urged unity and immediate action, while one representative of the youth environmental movement emphasized that “we’re all in this together.” The year was 1992, and the Earth Summit was underway in Rio de Janeiro.

Over 40,000 delegates had flown in for this ambitious conference, which sought global cooperation in the face of rising pollution, global warming, and deforestation. Delegates and performers included the headlining Placido Domingo, the Dalai Lama, Shirley Maclaine, and a “who’s-who” of early ‘90s hotness, with River Phoenix, Jeremy Irons, and Edward James Olmos in attendance among what one British paparazzo referred to as “all the nutters in the world.” By the end of the conference, it was already considered a failure. President Bush’s refusal to sign on to the keynote agreement, the Convention on Biological Diversity, had drawn fiery attacks by the presumptive Democratic nominee, Bill Clinton, who asserted that Bush had “abdicated both national and international leadership” in environmentalism, making the United States the “lone holdout” in a world that recognized the urgency of action. In response, Bush defended his record, emphasizing that “environmental protection makes growth sustainable.”

The world hinged on a great axis. The Berlin Wall had fallen only months prior and capitalism stood astride the global stage, triumphant. The American way of life had won, and all that remained was saving the planet. Bill Clinton would go on to be the first baby boomer president, setting the stage for that cohort to at last live up to the world-changing aspirations of their adolescence. It was to be a new and transformative era, one in which the mandates of capitalist economic expansion might be constrained in the service of sustainability. The Secretary General of the conference, Maurice Strong, acknowledged that the road ahead would be a difficult one, but “it will also be a journey of renewed hope, of excitement, challenge and opportunity, leading as we move into the 21st century to the dawning of a new world.”

And it was a new world—but not at all the one the organizers anticipated. 1992 heralded a significant turning point in the mechanisms that define our society: the neoliberal consensus became inviolate and fully bipartisan, with devastating consequences for the environment. Neoliberalism is a word that is often used—and overused—without explanation. George Monbiot has pointed out certain ideological hallmarks that can be taken as representative of the term: the primacy of the individual over the collective; that individual action should be expressed through consumer choices and consumerism; the exaltation of capital and a free market protected by the rule of law but unfettered via regulation; and reduced taxation, increased austerity, and governmental assistance for corporations instead of individuals, coupled with a devotion to privatization of public goods and services.

And it was a new world—but not at all the one the organizers anticipated. 1992 heralded a significant turning point in the mechanisms that define our society: the neoliberal consensus became inviolate and fully bipartisan, with devastating consequences for the environment. Neoliberalism is a word that is often used—and overused—without explanation. George Monbiot has pointed out certain ideological hallmarks that can be taken as representative of the term: the primacy of the individual over the collective; that individual action should be expressed through consumer choices and consumerism; the exaltation of capital and a free market protected by the rule of law but unfettered via regulation; and reduced taxation, increased austerity, and governmental assistance for corporations instead of individuals, coupled with a devotion to privatization of public goods and services.

It is this ideology, shared by centrist Democrats and “mainstream” Republicans alike for at least the last 40 years, that is responsible for unmitigated inequality, looming environmental collapse, and “our” complete inability—or refusal—to stop any of it.

Despite these realities, my childhood recollection of the early ‘90s is one of hope and determination. “Everyone” knew and believed certain truths, it seemed: global warming was real and an imminent danger, the Amazon Rainforest was being destroyed, dolphins were bloodily decimated to produce tuna. The corollary to this knowledge was the bone-deep conviction that, yes, these problems were real—but they were being taken care of. The good guys (Democrats) were now in charge, and the bad guys (Republicans) were in the rear view. Things seemed set to be sustainably tubular, organically rad, and bodaciously green.

Two pop culture artifacts from the era reflect this sense of optimism: 1990’s Captain Planet and 1992’s FernGully: The Last Rainforest. Both are products of the same “boomer ascendant” zeitgeist as the Earth Summit, full of laudable messages aimed at raising environmental consciousness. And both address the fundamental flaw in mainstream environmental movements—the neoliberal rot embedded at the roots. Their approach to this overarching issue, however, varies dramatically.

***Billionaire futurist Ted Turner had a simple belief. He was “the second smartest thing on the planet” behind only one entity: “cartoons, because they speak every language.” Possessed of messianic leanings, Turner’s desire to “save the world” fit in nicely with his desire to increase market share through the acquisition of cartoon conglomerate Hanna-Barbera.

Turner and his “chief environmental watchdog,” Barbara Pyle, were both involved in organizing the Rio Earth Summit, and both left feeling disappointed. They felt that the conference had achieved perhaps “ten percent” of its potential due to the compromises demanded by the United States in its pre-conference negotiations, with Pyle going on to say that the summit was more of a “jazz funeral… a wake.” In the run up to the Earth Summit, Turner and Pyle collaborated on a cartoon broadcast on Turner’s networks with a simple if wide-reaching aim: “to arm a generation with the knowledge to find more sustainable ways of living on the planet.” The successes and failures of that cartoon can be seen as a metonym for the successes and failures of the mainstream Western environmental movement operating within the liberal, or neoliberal, paradigm.

The first image of the first episode of Captain Planet and the Planeteers (1990-1992), “A Hero For Earth,” shows an idyllic, prelapsarian forest. Light shines upon a white rabbit hopping about, first in contentment, then in fear. The forest is being destroyed. Trees shatter, birds fall from their nests. A giant walking robot is the agent of this destruction. In the control room sits a grotesque, porcine figure in a pastiche of military uniforms. He snorts with glee and delivers exposition, in the curmudgeonly tone of Ed Asner: “Ha ha ha, with this giant land blaster I’ll be able to drill for oil anywhere!” His crony, Rigger, a wiry caricature of a “good ol’ boy” crossed with Salacious Crumb, responds affirmatively: “he he he, yeah boss, even in a wildlife sanctuary!”

The drill is extended from the walking machine. It penetrates the river below, thrusting through the water and into a glowing pink crack, smashing into a glass barrier. A single drop of liquid falls from the drill and lands on the face of a sleeping woman, draped in vaguely Medditeranean robes. She is awakened. She is Gaia, the living embodiment of the ecosphere.

This “subtext” is hardly sub. Captain Planet, the television show, begins with a rape—that of earth herself by the forces of industrialism. Gaia dismisses the invasion easily enough and repairs the fault, then remarks that she’s been asleep for a century and is now curious as to what those “silly humans” have been up to. We are treated to a flash of all the horrors of the 20th century’s environmental record.

Gaia decides that it is time to fight back. She summons adolescents from different regions of the world (with little more specificity for some beyond “Asia”) and includes a representative of the Soviet state. These are to be her soldiers: a diverse, multicultural coalition, speaking the international language (English with an accent), each one controlling a ring that corresponds to a different elemental control. The fifth team member from South America is given control over “heart.”

Gaia decides that it is time to fight back. She summons adolescents from different regions of the world (with little more specificity for some beyond “Asia”) and includes a representative of the Soviet state. These are to be her soldiers: a diverse, multicultural coalition, speaking the international language (English with an accent), each one controlling a ring that corresponds to a different elemental control. The fifth team member from South America is given control over “heart.”

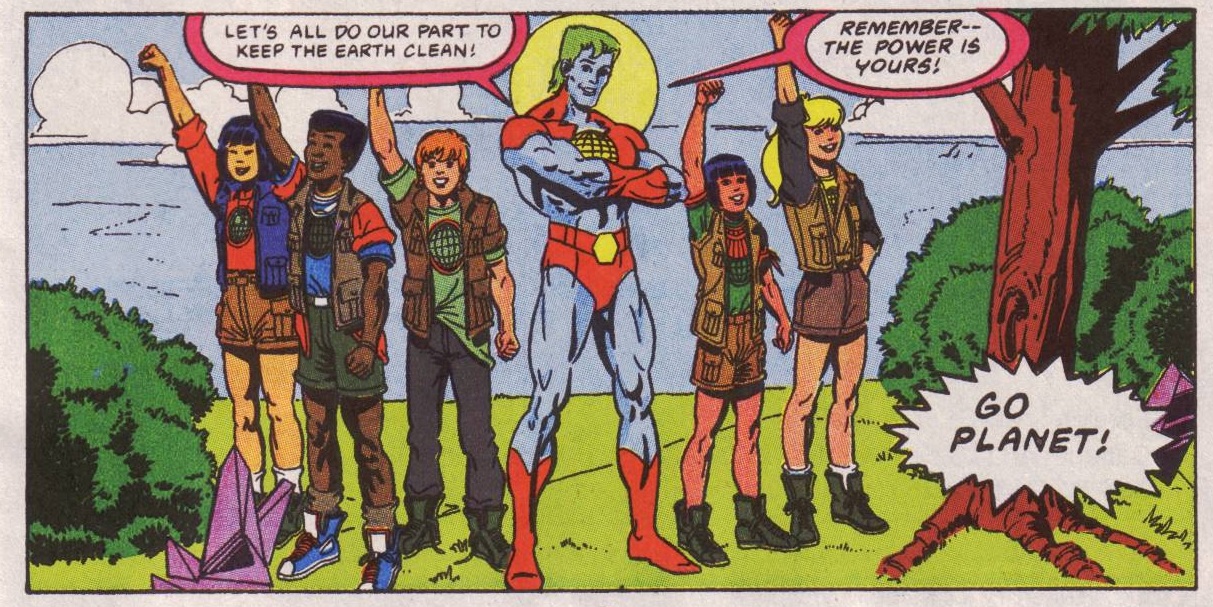

The Planeteers, teleported to Gaia’s base of “Hope Island” (the geography is very unclear), then fly north (in a carbon-emitting jet, despite Gaia’s proven ability to teleport) to confront the eco-villain. They are greeted by walruses covered in oil as the robot (now resembling an oil rig) drills. They fight the robot-drill but are forced to withdraw when the pigman threatens to spill his oil on the defenseless walrus. The team escalates, evoking the gestalt effect. By giving up their individual powers they can summon a greater warrior: Captain Planet himself, a mulleted superhero, the white, male, American leader of a diverse multicultural coalition. Again, the subtext is skin deep.

Captain Planet defeats the villains. Greedley escapes, though, and Rigger is given the equivalent of a slap on the wrist (dumped head first into a trash can) for abetting the destruction of a pristine ecosystem. In terms of semiotics, Greedley is the military-industrial complex and escapes any form of consequence; Rigger, just a “good-ol-boy” in search of a job, suffers no real punishment beyond temporary humiliation.

This first episode encapsulates the plot of essentially every episode: an “eco-villain” breaks the rules of conscientious capitalism and is confronted by the Planeteers, but ultimately defeats or traps them, after which they summon Captain Planet who, in turn, defeats the initial villain. The group then teaches the viewer, in an explicitly pedagogical segment, the ways they can help “save the planet.”

It is in this call to action (“the power is yours!”) that the fundamental flaws in the neoliberal approach to activism are most apparent. The Planeteers urge nothing but individual choices: encourage your family to drive less, carpool if you can, turn off the lights when you leave the room. In short: the problems are real but they are caused by consumer choices instead of systemic dysfunction, economic expansion, and unenforced regulation. It is this diffusion of responsibility that has proven a boon again and again to the system itself.

It is in this call to action (“the power is yours!”) that the fundamental flaws in the neoliberal approach to activism are most apparent. The Planeteers urge nothing but individual choices: encourage your family to drive less, carpool if you can, turn off the lights when you leave the room. In short: the problems are real but they are caused by consumer choices instead of systemic dysfunction, economic expansion, and unenforced regulation. It is this diffusion of responsibility that has proven a boon again and again to the system itself.

The effectiveness of this strategy is powerful. It can be seen in the way that disposable plastics manufacturers and soda companies devised the “Keep America Beautiful” campaign, absolving themselves of blame while shaming consumers for litter. It’s how 20 fossil fuel companies that have produced 35% of all carbon dioxide and methane released by human activities since 1965 have managed to get away with it.

Diffusion of responsibility is the voice that whispers, “Ah, the oceans are drowning in plastic? Should’ve recycled! Global warming threatens the vast majority of life in the biosphere? Well, it’s on you—should’ve carpooled!” It is the voice of the Planeteers when they tell us that “the power is yours,” but, crucially, not “ours.” There is no place for collective action in this conception of the world. The capitalist system itself is never questioned. The only role for the Planeteers is that of enforcing the “rules” of that system (“yeah boss, even in a wildlife sanctuary!”) and punishing the “eco-villains” (not Exxon or Dow, of course, but purposely exaggerated pigmen) that cause trouble. As a force, the Planeteers are reactive in response to pollution, never proactive in addressing the systems that cause and encourage these behaviors.

***FernGully was released in 1992, the same year as the Earth Summit, and, much like Captain Planet, sought to instill a message of environmentalism to its viewership. Unlike Captain Planet, however, FernGully directly addresses the systemic issues responsible for unsustainability and places the blame fully on human agency and ideology.

In revisiting the movie, I was surprised by its maturity. I recalled a simplistic fable in which “fairies fight a pollution-monster with Robin Williams as comic relief.” The reality was far more complex and adult. The fairies are disconcertingly sexualized, with the protagonist Crysta seemingly modeled after a “Dancing in the Dark”-era Courtney Cox, her curves accentuated by crop-top and thigh-slit dress. Her romantic interest Zak is a bronzed-blonde, big-sneakered, mulleted-hunk with a Walkman and baggy jeans. They are both, as described later in the film, “Bodacious Babes.”

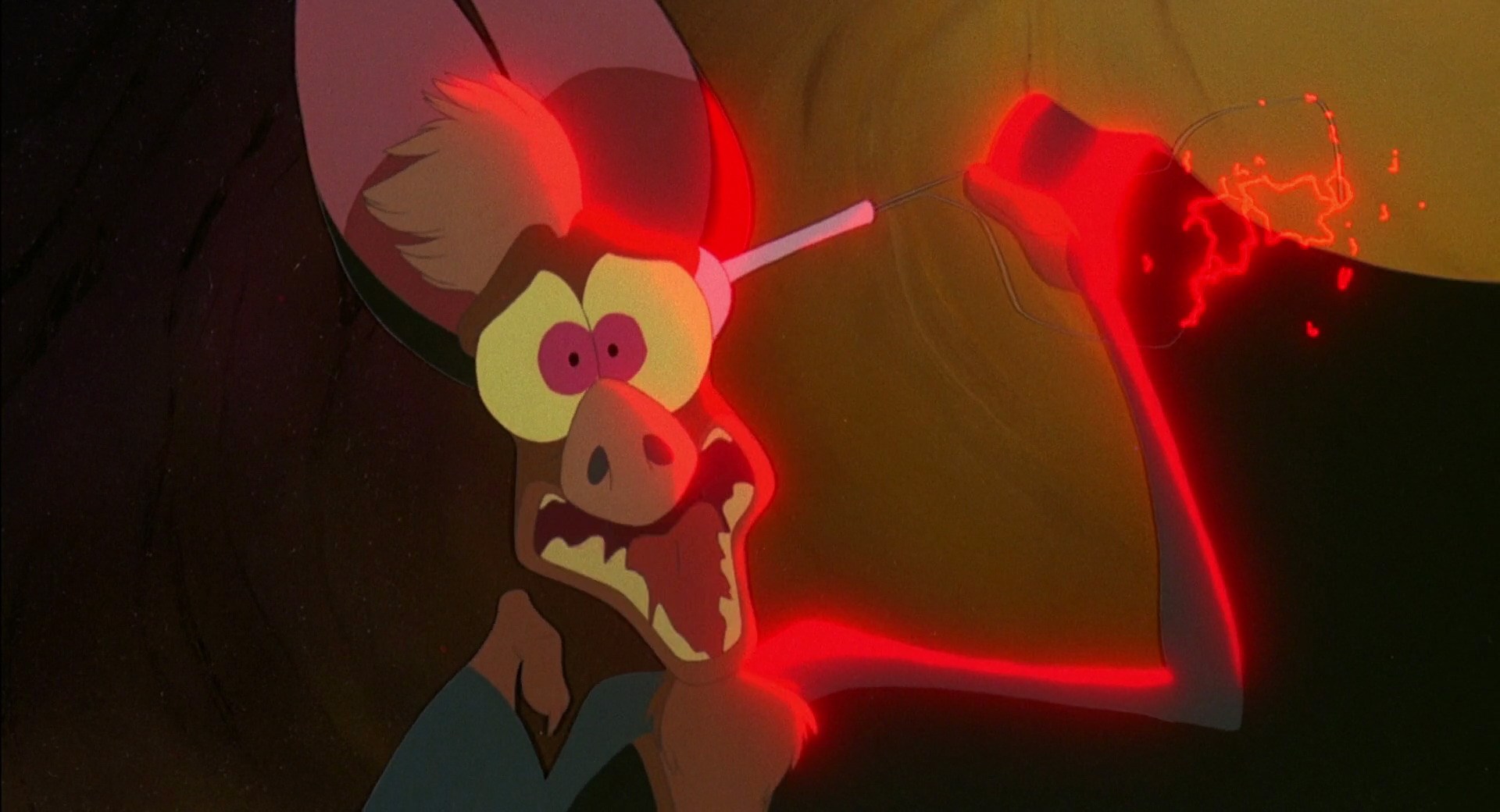

The part of the film I remembered most was Robin Williams’s Batty Koda. I recalled a character that was, much like Aladdin’s Genie, just an extension of his persona: a font of manic riffing and out-of-place impressions. Those aspects are there, of course, but the predominant trait of the character is the severe debilitation of trauma in the wake of torture at the hands of humans. Every aspect of the character is a testament to the fundamental evil of humanity’s relationship with nature. Batty (a bat) is a mauled escapee from a biology lab, the loose wires jammed into his brain depicted with pathos and visceral body horror. He suffers periodic seizures and dissociative episodes as a result of post-traumatic stress. He relates a trauma-rap (with that indelible early-’90s tone) wherein he describes being “brain-fried, electrified, infected and injectified, vivosectified and fed pesticides.” It is humor of the darkest kind, and the movie does not shy from it.

The part of the film I remembered most was Robin Williams’s Batty Koda. I recalled a character that was, much like Aladdin’s Genie, just an extension of his persona: a font of manic riffing and out-of-place impressions. Those aspects are there, of course, but the predominant trait of the character is the severe debilitation of trauma in the wake of torture at the hands of humans. Every aspect of the character is a testament to the fundamental evil of humanity’s relationship with nature. Batty (a bat) is a mauled escapee from a biology lab, the loose wires jammed into his brain depicted with pathos and visceral body horror. He suffers periodic seizures and dissociative episodes as a result of post-traumatic stress. He relates a trauma-rap (with that indelible early-’90s tone) wherein he describes being “brain-fried, electrified, infected and injectified, vivosectified and fed pesticides.” It is humor of the darkest kind, and the movie does not shy from it.

In short, this was not the trite, childish eco-fantasy I’d remembered, but rather one aimed at the kind of audience that might appreciate Tone Loc playing a hungry lizard and Cheech and Chong appearing as beetle-wranglers. This film was intended for a far wider and more discerning audience than Captain Planet and was the product of an independent animation studio adapting an original story with blatant environmental themes. Australian producer Wayne Young, enriched by the enormous success of 1986’s Crocodile Dundee, spent 15 years adapting the earnest environmental novel, which was written by his former wife Diane. The big-name stars of the movie worked for scale, forgoing significant payment due to the environmentalist message of what Young described in a 1992 issue of the Montreal Gazette as “a classically simple story… It won’t bend anyone’s brain to figure out what it’s all about.”

The plot of the film concerns a fairy society living in the lush Gondwana Rainforest near Mount Warning, part of what is today Wollumbin National Park in Australia. The fairies are tree guardians living in harmony with the natural world, and most have never seen a human. The movie begins with exposition from the leader, Magi, as she relates a story of long ago, when a primal force of destruction named Hexxus helped sever the harmonious bond between the tree fairies and the Aboriginal peoples of the region following a volcanic eruption. It is here that Hexxus’s identification with exploitative Western modes of thought is most apparent, his presence serving to separate the Indigenous Australians from FernGully itself. Hexxus was subsequently trapped in a tree and fairy society continued.

Crysta, her ‘90s bangs immaculate, is the protege of Magi and chafes under the restrictions of her society. One day she violates taboo by flying above the treeline. She sees a much wider world than she’d ever imagined, a vision of unending green marred by a plume of smoke in the distance. She then meets the aforementioned Batty, who seeks to warn the fairies of the horrors of encroaching humanity, his very body a testament; but, like Cassandra of Troy, he is unable to convince them of the impending threat. Batty’s presence as a victim of humanity is explicit and serves as an indictment of the original sin of Western environmental thought: humankind’s violent dominion over nature.

Crysta sets out to see the plume for herself, traveling through a defiled landscape to a logging site. She passes severed trees, their stumps marked with a bleed of red paint. The viewer is then introduced to mankind in the form of “the leveler,” a piece of forestry equipment based on a leveling track harvester but depicted as a horrific, smoking robot. It is this harvester that is most clearly coded as an abhorrence. The operators, Tony and Ralph, are depicted as bumbling slobs—but they are not evil. The machine itself—gleaming, fuming, jagged technology—is the force of evil. The act of technologically abetted forestry is explicitly identified as wrong.

Crysta sets out to see the plume for herself, traveling through a defiled landscape to a logging site. She passes severed trees, their stumps marked with a bleed of red paint. The viewer is then introduced to mankind in the form of “the leveler,” a piece of forestry equipment based on a leveling track harvester but depicted as a horrific, smoking robot. It is this harvester that is most clearly coded as an abhorrence. The operators, Tony and Ralph, are depicted as bumbling slobs—but they are not evil. The machine itself—gleaming, fuming, jagged technology—is the force of evil. The act of technologically abetted forestry is explicitly identified as wrong.

Crysta sees Zak Young, a young forester, and rescues him from a falling tree, accidentally shrinking him to fairy-size in the process. The two return to FernGully, where Zak at first hides his responsibility for the encroaching deforestation and generally just bros out with the fae, introducing them to cassette tape jams and accompanying Crysta to a narrow aquatic cave for a moist make-out that fades to black.

The leveler, meanwhile, cuts down and processes the tree imprisoning Hexxus, freeing him. Hexxus manifests as sludge (voiced by Tim Curry) and is delighted by the “clever, helpful” humans and the technology they’ve developed, expressing his belief that they’re “destined to be soulmates” with a bump-n-grind burlesque extolling the pleasure of “Toxic Love.” It is his intention to use “the machine they have provided” to convert the natural environment into capital, visualized as animals and trees turning into coins and bills. He then exercises his sole agency throughout the entire movie: impersonating Tony and Ralph’s boss through the radio and directing them to head to FernGully. The mechanism for their coercion is clear, as they are both excited at the prospect of “beaucoup overtime.”

This is a rich scene and one very much at odds with Captain Planet’s depiction of a well-regulated system subject to the malice of rule-breaking “Eco-villains.” It is capitalist consumerism—neoliberalism itself—that is the “machine they have provided” for the spirit of destruction. Hexxus revels in the machine, but it is not his: it is a human invention. Hexxus is clearly identified as the nameless, faceless voice of capitalism, the invisible engine powering the machine. He does not destroy, however—he provides economic incentives and lets the system work for him.

Back at FernGully, the disruption to the ecosystem is apparent in the poisoned rivers and dying vegetation. Crysta investigates and sees a vast clear-cut above the treeline. When she questions Magi as to whether or not it can be healed, Magi responds that she cannot because “a force outside of nature” is responsible, further identifying humanity as aberrant. Zak confesses, acknowledging that “humans did it. Humans did it all.” Zak informs them that their threat is a machine, defined as a “thing for cutting down trees.”

Back at FernGully, the disruption to the ecosystem is apparent in the poisoned rivers and dying vegetation. Crysta investigates and sees a vast clear-cut above the treeline. When she questions Magi as to whether or not it can be healed, Magi responds that she cannot because “a force outside of nature” is responsible, further identifying humanity as aberrant. Zak confesses, acknowledging that “humans did it. Humans did it all.” Zak informs them that their threat is a machine, defined as a “thing for cutting down trees.”

The fairies seem to accept their inevitable defeat and appear to retreat to a sacred tree, with Magi sacrificing herself to provide Crysta with a magic seed. The leveler, ridden by a laughing Hexxus, approaches the tree at the sacred heart of FernGully, its saws whirring implacably. Zak attempts to confront the leveler but is knocked to the ground.

Batty rescues Zak and tries to flee. Zak repays the rescue by physically manipulating the wires inserted in Batty’s brain, inducing a rapid-fire set of dissociative episodes that play out as Robin William’s comic impersonations set to a cocaine cadence. Batty is coerced into confronting the leveler when Zak triggers a “John Wayne”-type personality that charges the machine. Zak is thrown from Batty and lands on the windshield of the leveler, attempting to warn Tony and Ralph of his presence. They dismiss the warning until they see the actual physical manifestation of Hexxus and flee the cab, allowing Zak to enter and turn the machine off.

Hexxus is instantly diminished by the machine’s shutdown, wondering “what happened to the energy?” After a moment of audience relief, Hexxus rallies, now embodied as the fire from the burning fuel tank, growing as it prepares to consume FernGully after all. Crysta sacrifices herself by flying within Hexxus’s gaping maw, holding the seed. This is enough of a signal for the rest of the fairies to take collective action and “help it grow,” because “we all have a power and it grows when it shares.” This act sparks the regenerative power of nature to again bind Hexxus within a tree. Crysta is then reborn within a petal blossoming atop the tree.

Hexxus is instantly diminished by the machine’s shutdown, wondering “what happened to the energy?” After a moment of audience relief, Hexxus rallies, now embodied as the fire from the burning fuel tank, growing as it prepares to consume FernGully after all. Crysta sacrifices herself by flying within Hexxus’s gaping maw, holding the seed. This is enough of a signal for the rest of the fairies to take collective action and “help it grow,” because “we all have a power and it grows when it shares.” This act sparks the regenerative power of nature to again bind Hexxus within a tree. Crysta is then reborn within a petal blossoming atop the tree.

Crysta is reunited with Zak, rapturous that “Hexxus can never harm FernGully again.” Zak disabuses her of that notion by countering that Hexxus might not, but “humans still could,” explaining that he must return to human society to protect FernGully from further encroachment. He is returned to human size and finds Tony and Ralph, telling them “things have gotta change.” The forest, aided by the fairies, regenerates as a farewell gesture, and the movie ends with a dedication: “for our children and our children’s children.”

FernGully’s depiction of humanity as an inherently malevolent force in thrall to consumerism is a powerful one, but it was not all that far-reaching. The movie itself barely made back its budget, either because of its overt environmental messaging or simply because it wasn’t Disney. Its $32 million box office gross was about six-percent of Robin Williams’s other animated release that year, Aladdin.