Jesse Walker / March 31, 2020

I can tell you the day the so-called Vietnam syndrome started to die. On November 12, 1979, four and a half years after the last American troops fled Saigon, a new single was shipped to record stores and radio stations, a ballad by the fellow who’d had a smash hit a year before with “The Gambler.” Kenny Rogers’ new song was “Coward of the County,” written by Roger Bowling and Billy Edd Wheeler. I remember the first time I heard it that November, listening to the radio in the car with my mom on our way to the supermarket.

He was only 10 years old when his daddy died in prison

I looked after Tommy, ’cause he was my brother’s son

I still recall the final words my brother said to Tommy

‘Son, my life is over, but yours has just begun

‘Promise me, Son, not to do the things I’ve done

‘Walk away from trouble if you can

‘Now it won’t mean you’re weak if you turn the other cheek

‘I hope you’re old enough to understand

‘Son, you don’t have to fight to be a man’

We arrived before the song was over, but she kept the motor running in our parking spot so we could hear how the story ended.

I can’t say I understood all the cultural context that surrounded that record on the radio. I was vaguely aware that there had been a war in Vietnam, that the US had lost, and that a lot of people, including most of the grown-ups I’d heard talking about such things, didn’t want to get drawn into a war like that again. I didn’t know that this reluctance to fight was upsetting a large swath of the foreign policy establishment, or that those mandarins of empire had begun to call this war-wariness the “Vietnam syndrome.” I was nine years old. There was a lot I didn’t know.

There’s someone for everyone, and Tommy’s love was Becky

In her arms he didn’t have to prove he was a man

One day while he was working, the Gatlin boys came calling

And they took turns at Becky, and there was three of them

I didn’t know, for example, what “they took turns at Becky” meant. Perhaps I thought they had been making fun of her. If you are of a certain age, you may have had a holy-shit moment at some point in your teens or later—a day a DJ played that song you used to sing along to as a kid, and you suddenly realized it had a gang rape in it.

The Gatlin boys just laughed at him when he walked into the barroom

One of them got up and met him halfway across the floor

When Tommy turned around they said, ‘Hey look, old Yellow’s leaving’

But you could’ve heard a pin drop when Tommy stopped and locked the door

Twenty years of crawling was bottled up inside him

He wasn’t holding nothin’ back, he let ’em have it all

When Tommy left the barroom, not a Gatlin boy was standing

He said ‘This one’s for Becky’ as he watched the last one fall

When I heard that as a boy, I assumed that Tommy had beaten up the Gatlins. But the lyrics are Delphic, and they could easily describe a man methodically firing a gun. Either way, I got the intended moral of the tale even before I heard Tommy spell it out a moment later:

I promised you, Dad, not to do the things you’ve done

I walk away from trouble when I can

Now please don’t think I’m weak, I didn’t turn the other cheek

And Papa, I sure hope you understand

Sometimes you gotta fight when you’re a man

* * *

In August 1980, Ronald Reagan spoke to a Chicago gathering of the Veterans of Foreign Wars. “For too long, we have lived with the Vietnam syndrome,” the presidential candidate said. “As the years dragged on, we were told that peace would come if we would simply stop interfering and go home. It is time we recognized that ours was, in truth, a noble cause. A small country newly free from colonial rule sought our help in establishing self-rule and the means of self-defense against a totalitarian neighbor bent on conquest.”

As a history of how the Vietnam War began, it was nonsense. But as a familiar tale of good and evil, it had resonance—the kind of resonance that will take you to #1 on the Billboard country chart and #3 in the pop top 10. “Sometimes you gotta fight,” the candidate could have added. Maybe in the barroom, where the Gatlin boys were jeering. Maybe in Nicaragua, which had a leftist revolution four months before “Coward” shipped to stores. Maybe in El Salvador, which was less than a month into a 12-year civil war the first time “Coward” aired on the radio. Maybe Angola. Or Grenada. Or Kuwait. All sorts of countries cycled through the news from 1975 to 1991. They had different names, but for a certain sort of speechwriter they all were Becky, surrounded by those Gatlin boys bent on conquest.

I’m not saying that Bowling or Wheeler had Vietnam in mind when they wrote “Coward.” Maybe they did; maybe they didn’t. Songs about sexual violence and bloody revenge are as old as country music—older!—and you could have penned something a lot like this song in 1929 as easily as in 1979. You didn’t have to be thinking about the war to want to buy the record either. It had a well-told story and an infectious chorus, and it might have been a hit a decade earlier too.

I’m not saying that Bowling or Wheeler had Vietnam in mind when they wrote “Coward.” Maybe they did; maybe they didn’t. Songs about sexual violence and bloody revenge are as old as country music—older!—and you could have penned something a lot like this song in 1929 as easily as in 1979. You didn’t have to be thinking about the war to want to buy the record either. It had a well-told story and an infectious chorus, and it might have been a hit a decade earlier too.

But it wasn’t the hit Kenny Rogers had a decade earlier. His most successful song of 1969 had been a rather different record, a cover of Mel Tillis’ haunting “Ruby, Don’t Take Your Love to Town.” That one’s a gothic tale about a veteran, paralyzed in a “crazy Asian war,” who sits unable to do anything but plead while his wife dolls herself up for a night with her lover. He has violent urges bottled up inside him too, just like Tommy. Really ugly urges: “If I could move,” he tells us, “I’d get my gun and put her in the ground.” But he’s “not the man I used to be,” and so he’s helpless. Now there’s a grotesque twist on “Sometimes you gotta fight when you’re a man.”

Ten years later, Tommy would be manly enough by the code of these songs to take his revenge, and he’d have enough moral grounding to direct his violence at a trio of thugs rather than his mate. And two years after that, when the song became a TV movie, his violence would find another outlet. After beating the Gatlin boys in a wild bar fight, young Tommy marries Becky and enlists to fight in World War II—“because I have so much here to stand up for and protect.”

* * *

We heard that phrase “Vietnam syndrome” a lot in the ’80s, as pro-war intellectuals fretted that Americans weren’t willing to fight anymore. “Our communications on Nicaragua have been a failure,” President Reagan grumbled in his diary in 1985. “90% of the people know it is a communist country but almost as many don’t want us to give the Contras $14 mil. for weapons. I have to believe it is the old Vietnam syndrome. They are afraid we’re going to get involved with troops.”

The more hawkish Reaganites directed this ire not just at gun-shy civilians but at quagmire-wary members of the military. Some of Reagan’s appointees even directed it at each other. When Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger laid out the so-called Weinberger Doctrine in 1984—a set of six principles he thought should limit the use of American combat troops—Secretary of State George Shultz seethed: “This was the Vietnam syndrome in spades, carried to an absurd level,” he later wrote.

The hawks hailed Washington’s quick victory in the 1991 Gulf War as the end of the affliction. “By God, we’ve kicked this Vietnam syndrome,” President George H.W. Bush crowed to the American Legislative Exchange Council. It hadn’t been 20 years of crawling—hell, they hadn’t been crawling at all—but for a certain sort of Washington functionary, any constraint on their ability to project power feels like a humiliation.

But war-wariness, and war-weariness, aren’t so easy to extinguish. The Vietnam-specific version of the syndrome may have died, but Americans still had rational reasons to want to avoid quagmires abroad; the next war in the Gulf region would remind the country just how much damage a march into battle can do. As public opinion started to turn against war, the phrase “Iraq syndrome” didn’t become as popular as its Southeast Asian predecessor; but it did start to float around certain D.C. circles. (Others fell back on their old vocabulary. Norman Podhoretz, the first-generation neoconservative who once had worried that even Reagan’s foreign policy evinced “the sickly inhibitions against the use of military force,” wrote in 2007 that the media’s coverage of the second Iraq war had proved “the Vietnam syndrome was alive and well.”)

But war-wariness, and war-weariness, aren’t so easy to extinguish. The Vietnam-specific version of the syndrome may have died, but Americans still had rational reasons to want to avoid quagmires abroad; the next war in the Gulf region would remind the country just how much damage a march into battle can do. As public opinion started to turn against war, the phrase “Iraq syndrome” didn’t become as popular as its Southeast Asian predecessor; but it did start to float around certain D.C. circles. (Others fell back on their old vocabulary. Norman Podhoretz, the first-generation neoconservative who once had worried that even Reagan’s foreign policy evinced “the sickly inhibitions against the use of military force,” wrote in 2007 that the media’s coverage of the second Iraq war had proved “the Vietnam syndrome was alive and well.”)

If the syndrome was still alive, so was the tale pundits told to extinguish it. In 2014, when President Barack Obama sent troops to the Middle East to fight ISIS, New York Times columnist David Brooks celebrated with a familiar story. Exaggerating Obama’s reluctance to use the military, Brooks wrote:

History is full of reluctant leaders… President Obama is the most recent. He recently gave a speech on the need to move away from military force. He has tried to pivot away from the Middle East. He tried desperately to avoid the Syrian civil war. But as he said in his Nobel Peace Prize lecture, “Evil does exist in the world.” No American president could allow a barbaric caliphate to establish itself in the middle of the Middle East.

Obama is compelled as a matter of responsibility to override his inclinations. He’s obligated to use force… Everybody is weighing in on the strengths and weaknesses of the Obama strategy. But the strategy will change. The crucial factor is the man.

It’s the clunkiest remake you’ll ever hear of “Coward of the County.” But it probably won’t be the last one.

Jesse Walker is books editor of Reason and the author, most recently, of The United States of Paranoia: A Conspiracy Theory (HarperCollins).

Jesse Walker is books editor of Reason and the author, most recently, of The United States of Paranoia: A Conspiracy Theory (HarperCollins).

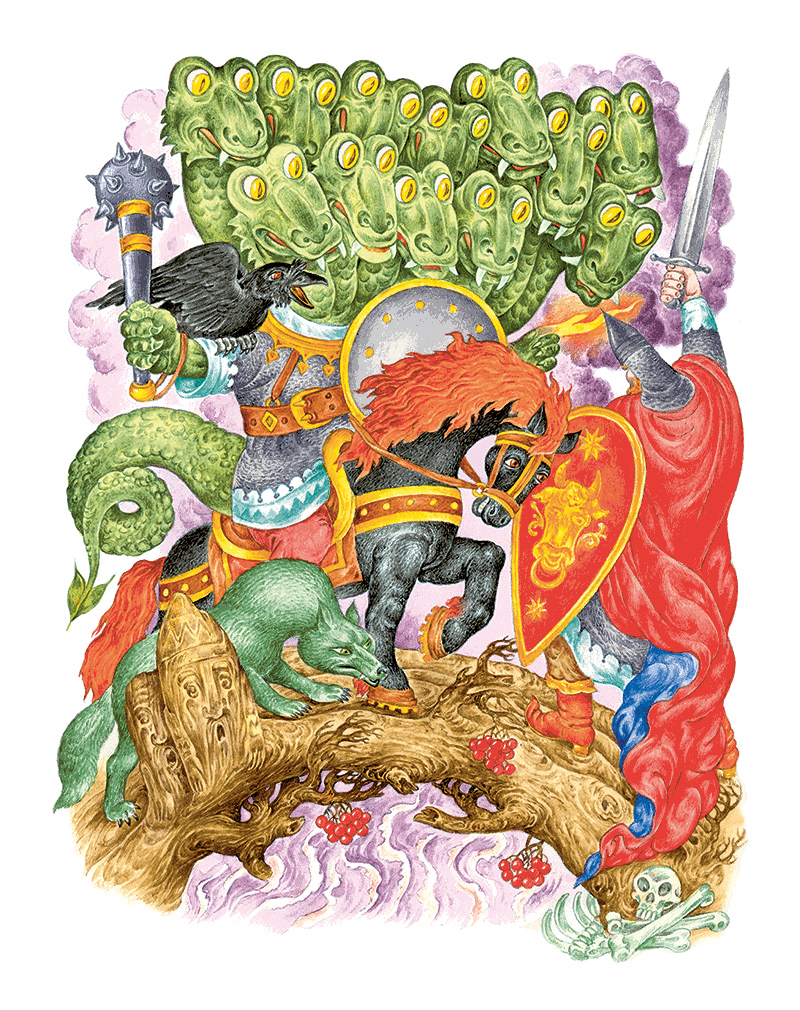

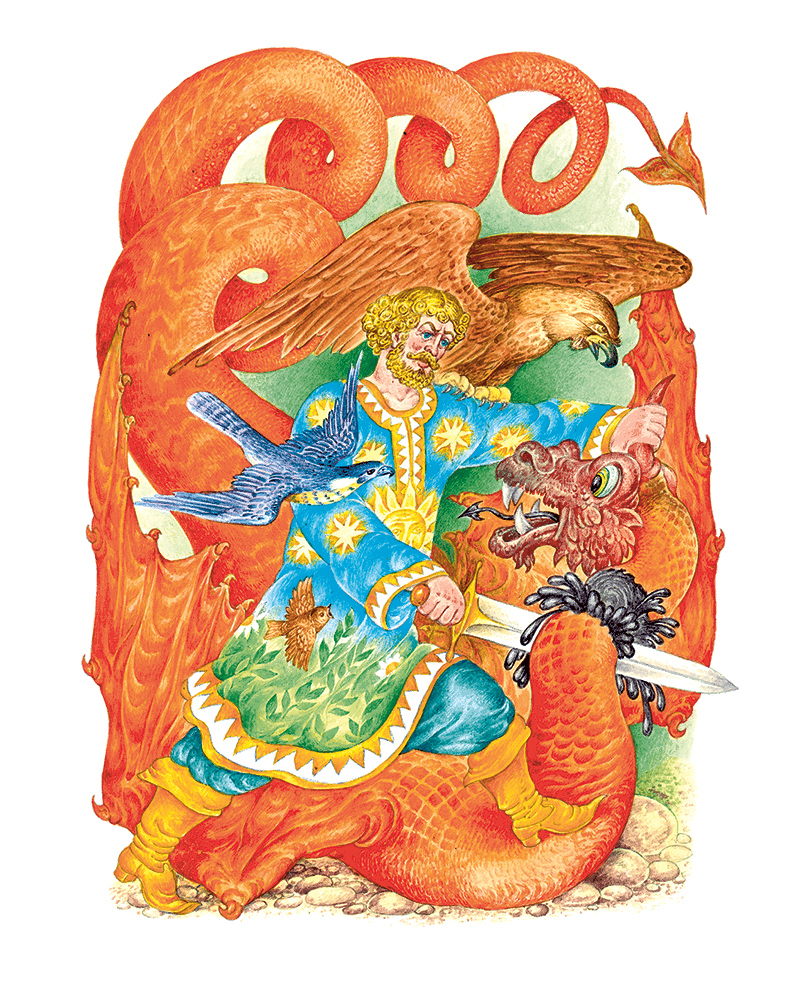

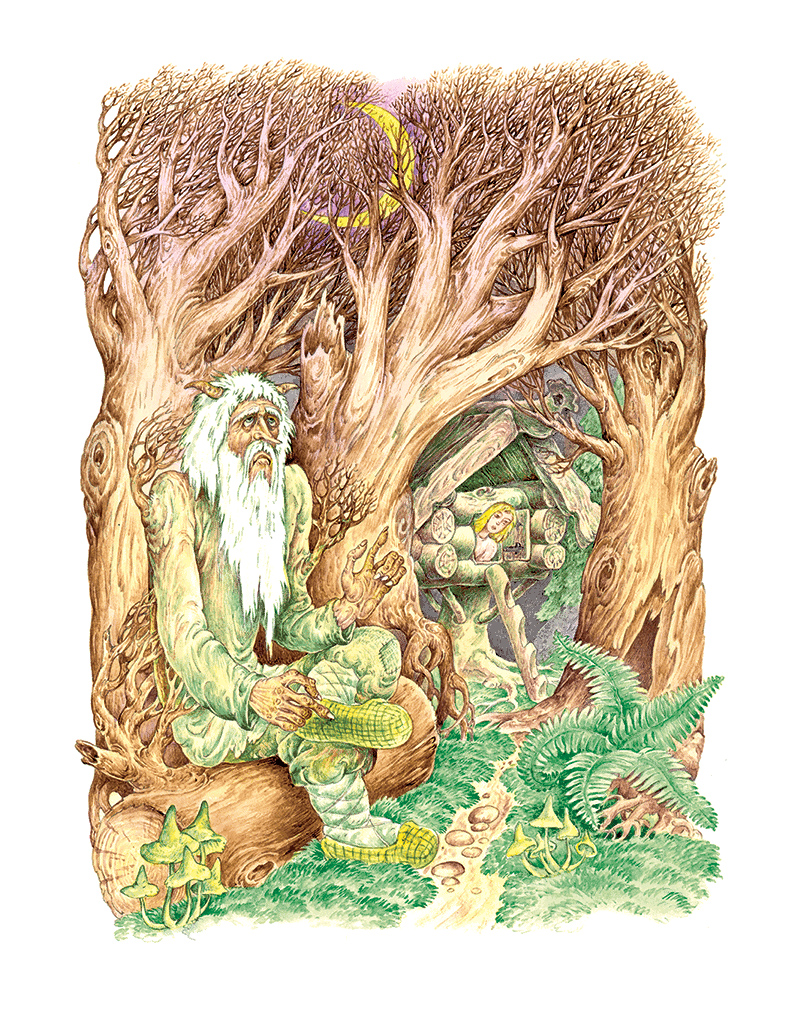

Return to the Würstreich with the newest game from GOBLINKO! DUNGEON BREAKOUT is a heavily flavored, tile placement party game, set in the same world and populated by the same weird characters and creatures as DUNGEON DEGENERATES: Hand of Doom. With easy-to-learn rules and fast game play action, DUNGEON BREAKOUT will be a hit with any crowd!

Return to the Würstreich with the newest game from GOBLINKO! DUNGEON BREAKOUT is a heavily flavored, tile placement party game, set in the same world and populated by the same weird characters and creatures as DUNGEON DEGENERATES: Hand of Doom. With easy-to-learn rules and fast game play action, DUNGEON BREAKOUT will be a hit with any crowd!