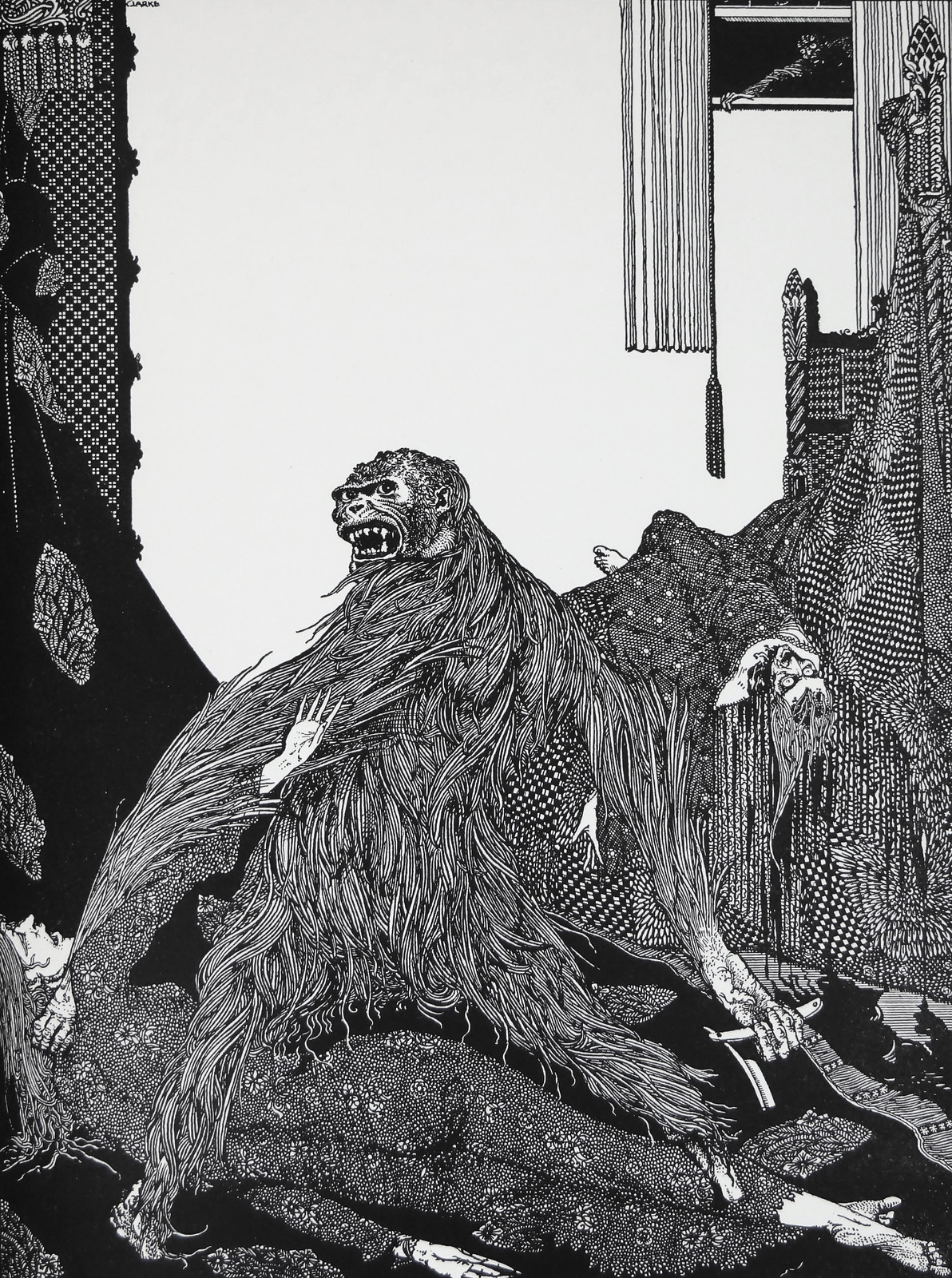

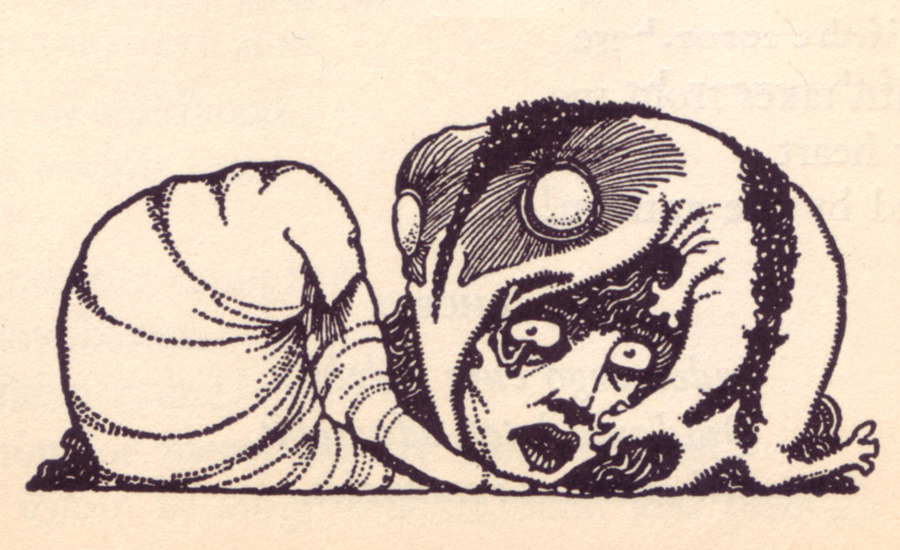

Karl Hodina (1935 - 2015) - The Virgin as Devil

"Alongside artists such as Arik Brauer, Ernst Fuchs and Rudolf Hausner, he is one of the representatives of the Vienna School of Fantastic Realism."

Artwork and quote found at Dorotheum.

Original Roleplaying Concepts

Exhibit / December 5, 2019

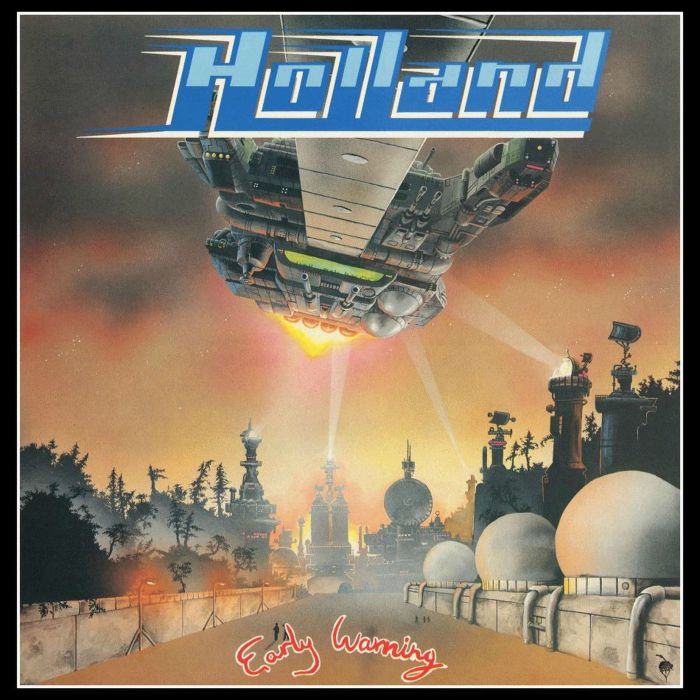

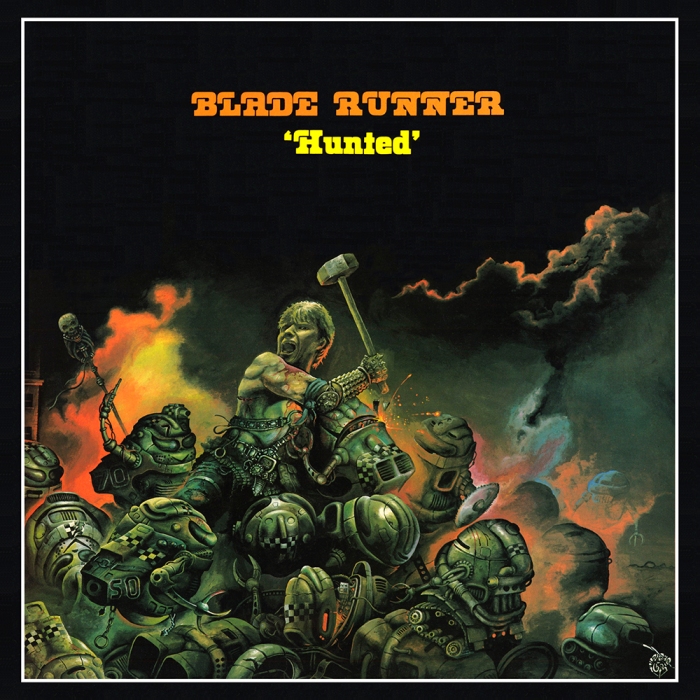

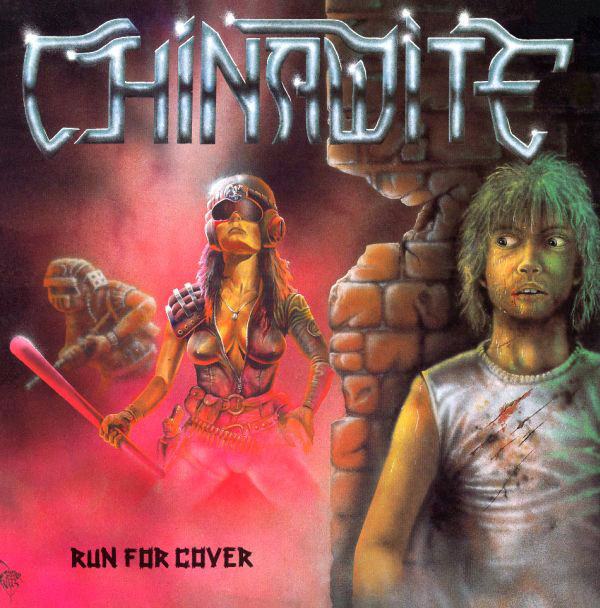

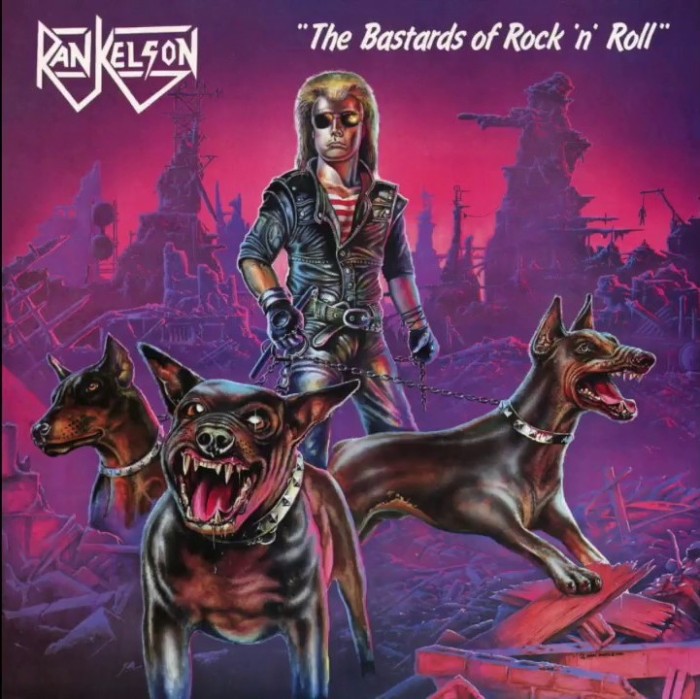

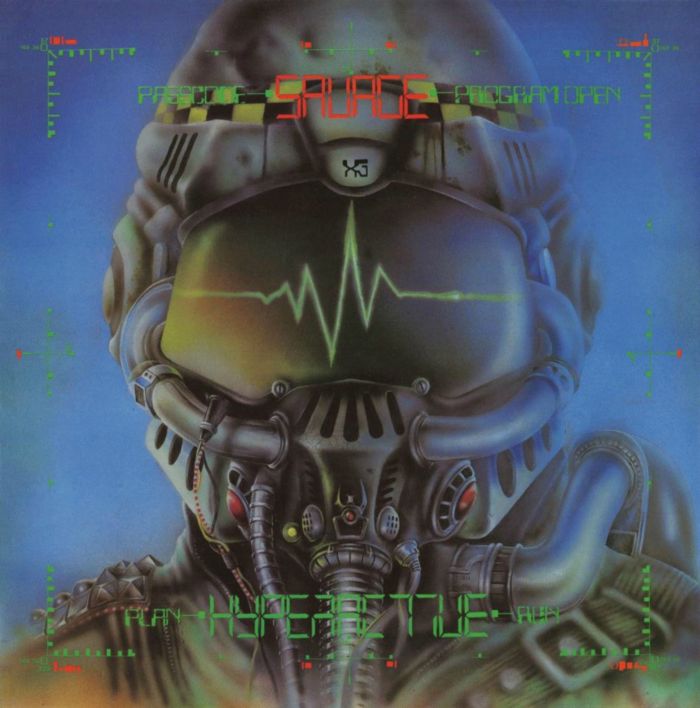

Object Name: Heavy Metal LP Cover Art

Maker and Year: Garry Sharpe-Young, 1983-1987

Object Type: Artwork

Description: (Richard McKenna)

Though active for only a brief period of time, artist Garry Sharpe-Young created a series of LP covers that provide a thrilling miniature survey of the mental landscapes of the British heavy metal music scene of the 1980s. The covers—all produced between 1983 and 1987—capture the lurid euphoria of a particular period of metal’s history when, revitalized by the energy of punk, the so-called New Wave of British Heavy Metal—known to metallers by the sacred and unpronounceable acronym “NWOBHM”—brought an injection of creativity and excitement to a genre many considered moribund, suffocated under the flaccid weight of its own juvenile clichés. Assisted by a DIY approach that was also borrowed from punk, the NWOBHM arrived in the late ’70s with its own thrilling grab-bag of juvenile clichés, or in the worst case took a hungry new approach to those that already existed.

The motifs in Sharpe-Young’s covers will be familiar ones to anyone versed in metal’s preferred leitmotifs—post-apocalyptic wastelands, science fiction, sword and sorcery slop, the occult, war and battlefields, technology and death—but just as the NWOBHM headbangers brought a new prole ferocity and rawness to their music, Sharpe-Young approached his subject matter with a fresh and exciting garishness and spontaneity that clearly displayed the influence of comics and fantasy art (Frank Frazetta, notably), as well as of the artwork flooding out of the nascent video game industry. And what the illustrations might have lacked in slick professionalism they more than made up for with the brute force of their hugely enjoyable silliness.

Despite the relatively slight size of his visual oeuvre (he was apparently inspired by the sight of one of the many particularly awful album covers scattered throughout British fortnightly metal bible Kerrang), it possesses a distinctive aesthetic that, uniquely, doesn’t really resemble anyone else, and its combination of naiveté, technical flair, and all-out punkish chutzpah gives it a vividness and freshness that raises it above most of its peers. And if we can judge by these twelve covers, it seems fair to note that—by the admittedly low standards of the metal scene of the time—Sharpe-Young’s artwork is surprisingly un-sexist, as the intimidating huntress on the cover of Chinawite’s Run for Cover testifies. Something about his creations hints that the late Sharpe-Young was more self-aware than many of his peers in the ’80s, and in fact he went on to became a prominent journalist of the international metal scene.

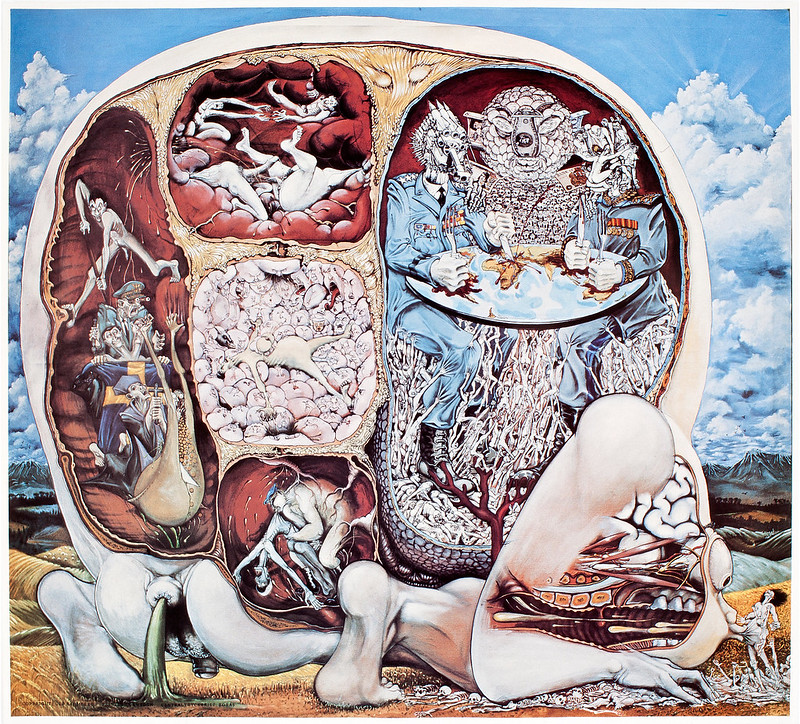

Painting No. 21 (side A), 1970-73

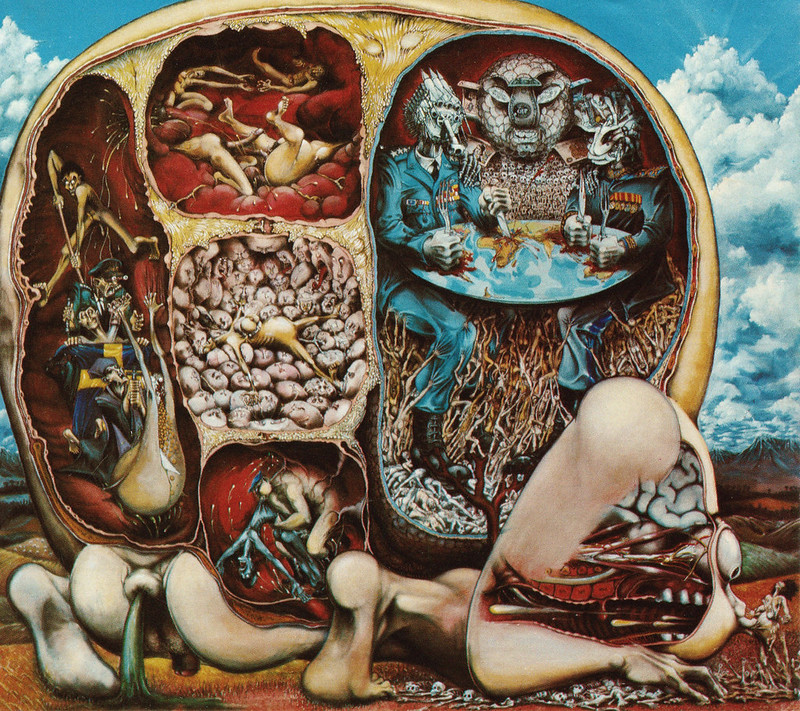

Painting No. 21 (side A), 1970-73 Painting No. 21 (side B), 1970-73

Painting No. 21 (side B), 1970-73 Painting No. 21 (side B), 1970-73

Painting No. 21 (side B), 1970-73 Grabado #18, 1973

Grabado #18, 1973 Gears, 1960

Gears, 1960 Title Unknown, 1979

Title Unknown, 1979 Flintskallig, 1994

Flintskallig, 1994 Joint Engineering

Joint Engineering Title Unknown, 1979

Title Unknown, 1979  Painting 1923, 1960

Painting 1923, 1960 Title Unknown, 1961

Title Unknown, 1961 On the battle front, nothing new, 1990-91

On the battle front, nothing new, 1990-91 Kroppsväcktaren, 1984

Kroppsväcktaren, 1984 Kapitoleum

Kapitoleum Snovit

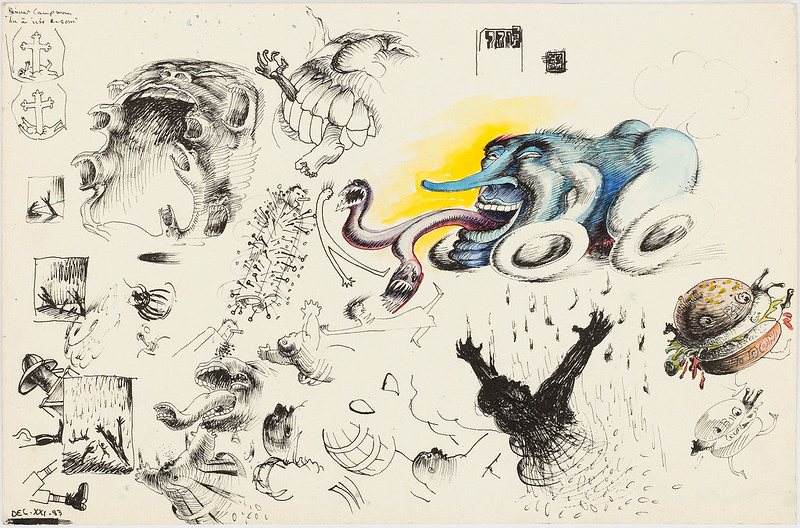

Snovit Sketch for 34 o'clock

Sketch for 34 o'clock Sketch for painting no 26

Sketch for painting no 26 Mussepiggpartiet

Mussepiggpartiet Untitled sketch

Untitled sketch Title Unknown, 1991

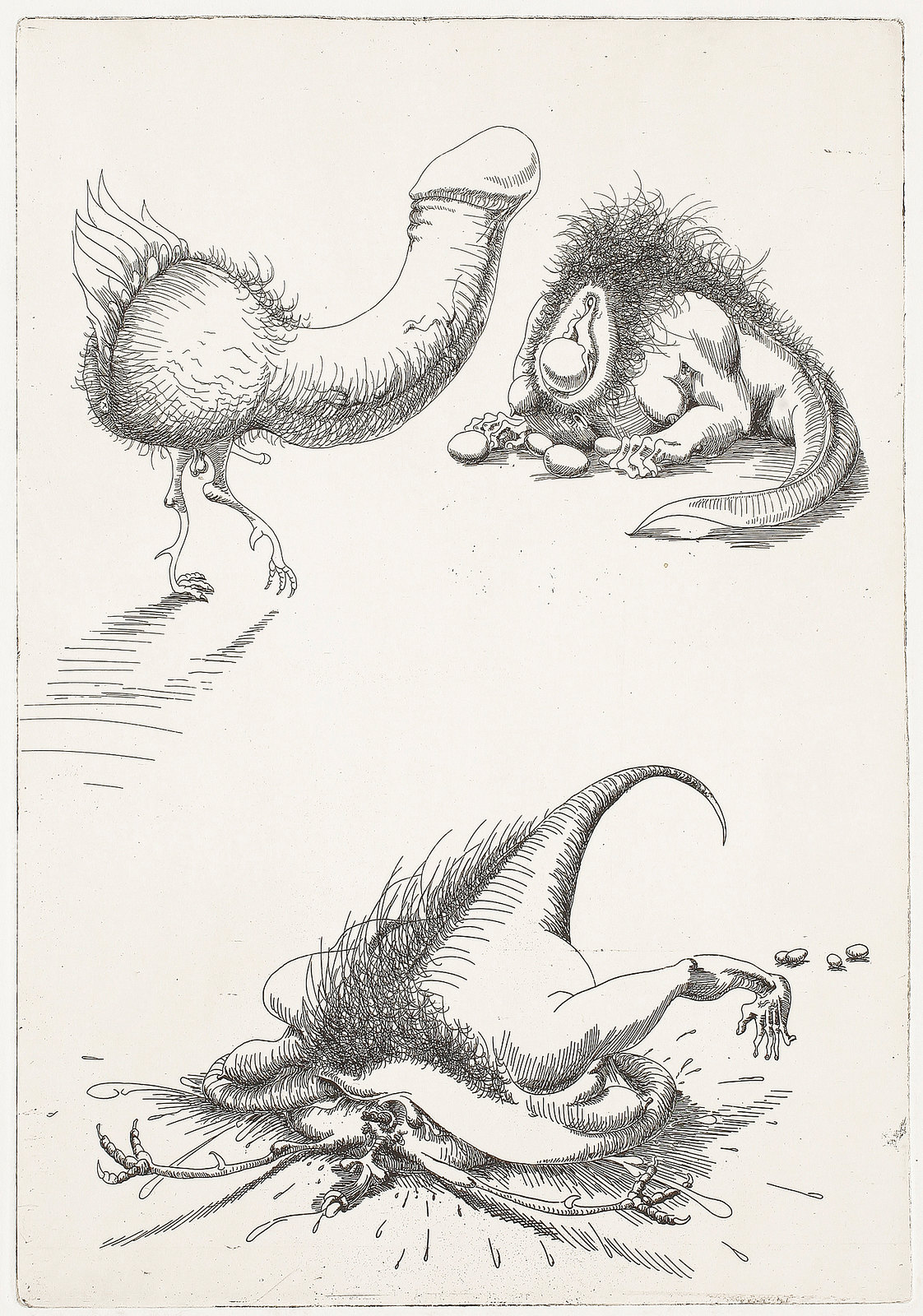

Title Unknown, 1991 Etching No. 14, 1966

Etching No. 14, 1966 Sketch for painting 34

Sketch for painting 34

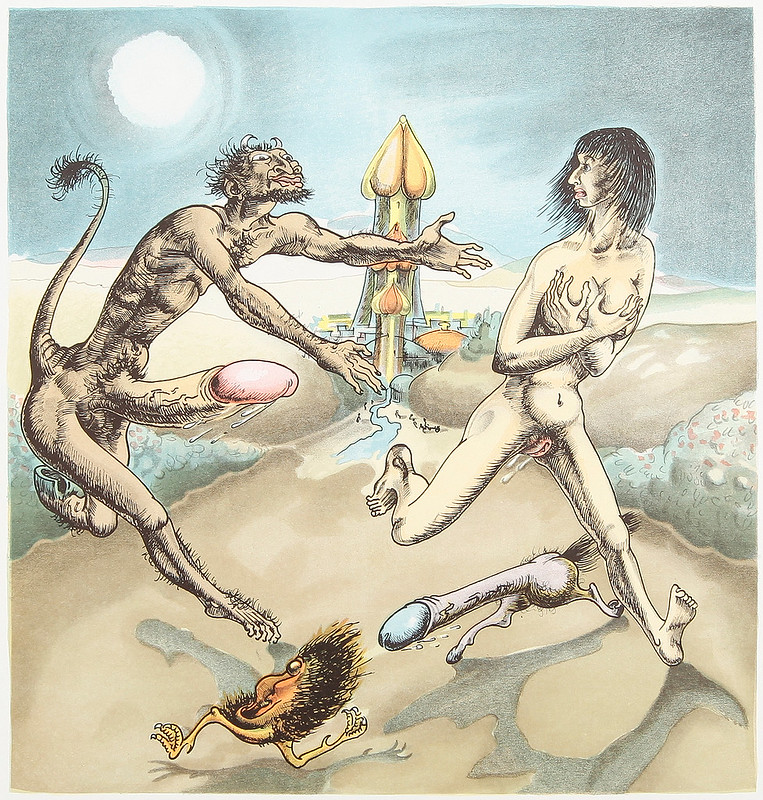

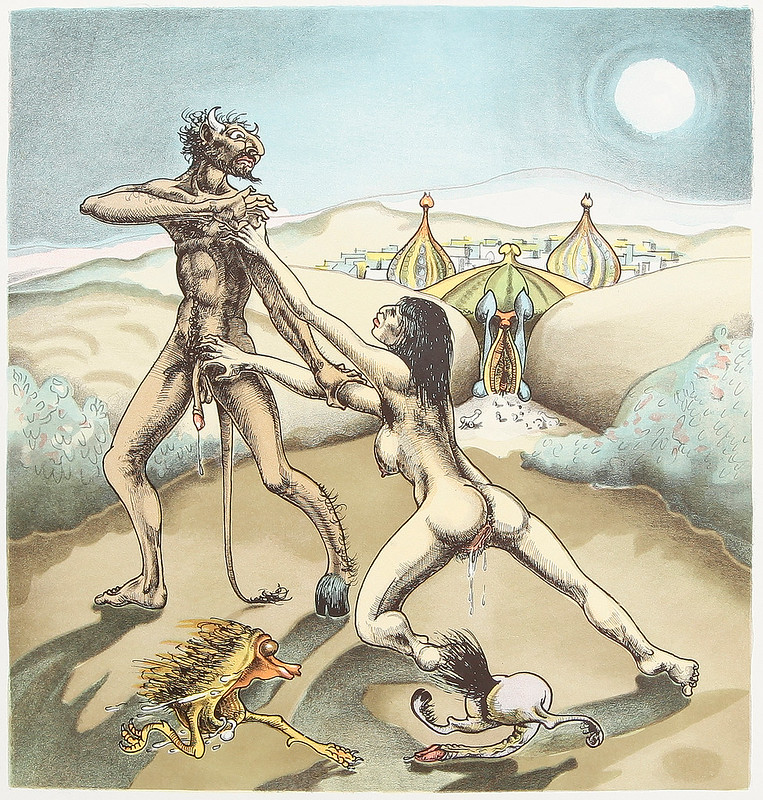

Sexual Motifs 3

Sexual Motifs 3 Sexual Motifs 2

Sexual Motifs 2 Sexual Motifs 1

Sexual Motifs 1

Sexual Motifs 4" See more at Rahmberg's website.

Sexual Motifs 4" See more at Rahmberg's website.  Artwork found at Bukowskis.

Artwork found at Bukowskis. Exhibit / December 4, 2019

Object Name: Ronco advertisements

Maker and Year: Ronco Teleproducts, Inc./Ronco, Inc., 1970s-1984

Object Type: Television advertisements

Video Source: starbond6/YouTube

Description: (Michael Grasso)

During broadcast television’s heyday in the 1970s, the American airwaves presented a series of advertising strata over the course of the broadcast day. The mornings and early afternoons would see household and kitchen products meant to appeal to housewives; toys and snacks and sugary breakfast cereals appeared once the kids got home from school; cars and medicines and other products with broad appeal would show up during prime time. As for late nights and overnights, no one haunted the cheap television commercial breaks quite like Ronco. For two decades—from 1964 to 1984—the company, founded by second-generation gadget salesman Ron Popeil, zapped countless catch phrases into the brains of the American TV-viewing audience. Presenting its array of multi-purpose household gadgets in a breathless, urgent style to fit into a half-minute or full-minute commercial slot, Ronco set the standard for the late-night direct mail sales pitch.

This type of TV ad came directly from Ron Popeil’s experience as an in-person hawker of the kitchen vegetable slicers that his father Sam and uncle Raymond had invented. Ron sold the slicers everywhere in his twenties: from the counter at Woolworths locations in Chicago to county and state fairs throughout the Midwest. By the early ’60s, Ron saw the potential of doing demonstrations on television, and bought cheap airtime on regional stations in Tampa, Florida and the Midwest in 1964, branding his father’s and uncle’s choppers as the now-legendary Veg-O-Matic, giving pop culture the first of many Ronco catchphrases: “It slices! It dices!” The Veg-O-Matic was only the beginning. By the early 1970s, Ronco Teleproducts had dozens of products on offer, none of which had a price point higher than $19.99.

The video above is an internal product reel featuring the kinds of products that Ronco presented from its 1970s heyday right up until the company’s first bankruptcy and dissolution in 1984. Many of these ads are Christmas-themed, as the modest Ronco price points made their products “great Christmas gifts.” The “Ronco Gift Center” (with its “As seen on TV” legend) featured in the first ad demonstrates that while Ronco made a good chunk of its sales through direct mail thanks to its TV ads, the company also used brick-and-mortar discount outlets to replicate the “impulse buy” mood that its TV ads so expertly cultivated. The consumer electronics revolution in the mid-to-late 1970s allowed Ronco to supplement its purely mechanical gadgets (such as the Ronco inside-the-eggshell Egg Scrambler and the “amazing no-spill” all-temperature Ronco AutoCup) with more and more electronic items. The gradual turn against public smoking in America in the ’70s led to the design and sale of Ronco’s various air purifiers like the Ronco Smokeless Ashtray, and no Ronco electronic toy is better known than “Mr. Microphone,” a low-power radio transmitter in a hand-held microphone that allowed the user to broadcast their voice out of a nearby FM radio. America’s love of home entertainment equipment in the late ’70s also allowed Ronco to capitalize by carving out a niche of gadgets for your gadgets, like the Ronco Battery Tester and the Ronco Record Vacuum.

The second half of this commercial reel features Ronco’s various music compilations on LP records; the array of artists and songs on offer (a mix of disco and funk hits, easy-listening hits from long-haired sensitive songwriters, and occasional hard rockers) show that Ronco’s music division, like its gadgets, peaked in the late 1970s. Like its rival K-tel, Ronco bought the rights to recent middling hit singles and put them all on one themed LP, making sure the consumer knew these were no sound-alikes (“Original hits by the original artists!”).

With the rise of cable television in the 1980s, Ronco’s approach of buying cheap late-night commercial time on over-the-air stations became diluted. The decision to expand into electronics also had an effect, as Ronco gadgets like the CleanAire air purifier didn’t match up to similar products on offer from big electronics makers. As mentioned above, the company filed for bankruptcy in 1984. But Ron Popeil himself and countless imitators would find new homes on the late-night airwaves during the rise of the full-length half-hour infomercial in the early 1990s, as well as on dedicated home shopping cable networks.

Lindsay Oxford / December 3, 2019

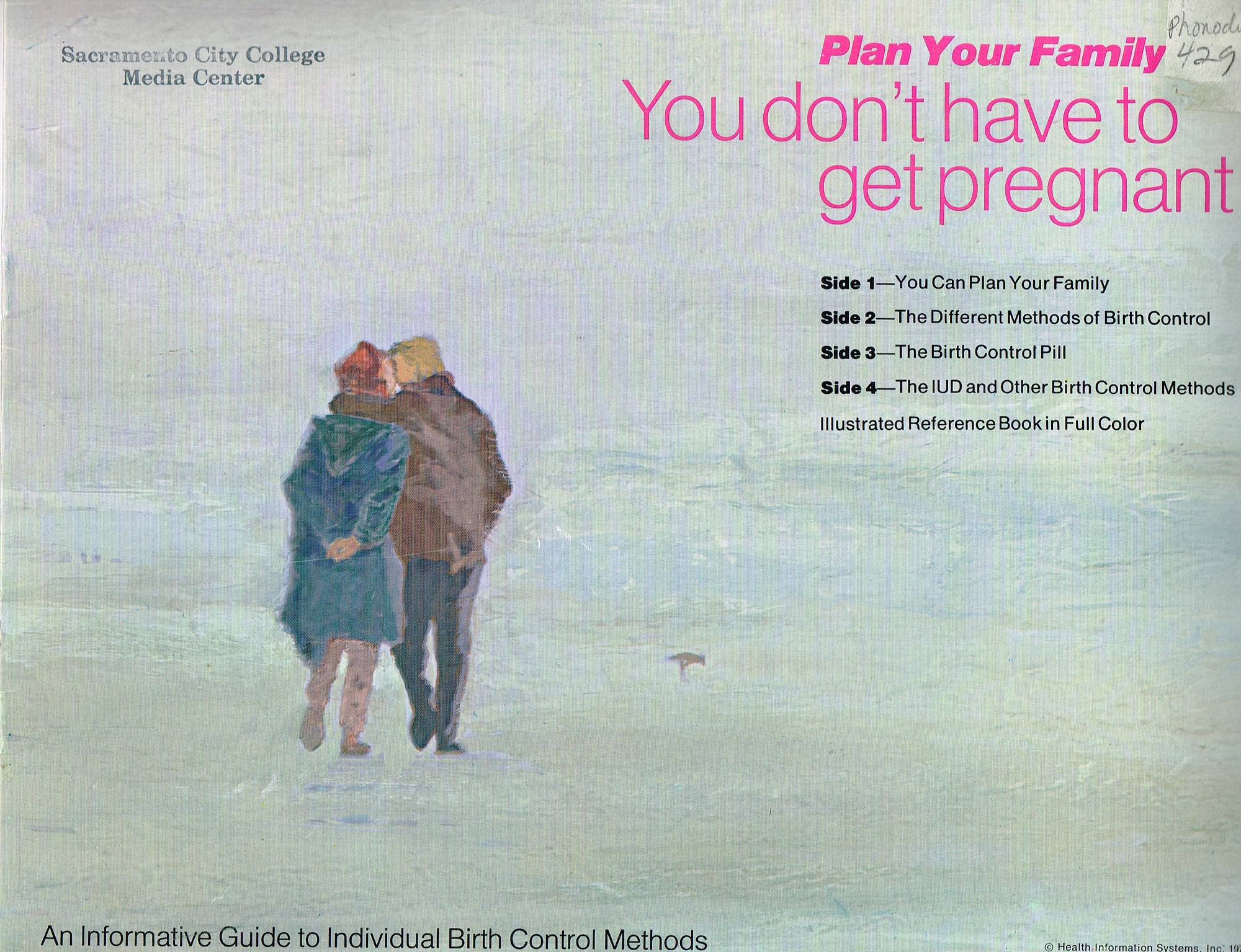

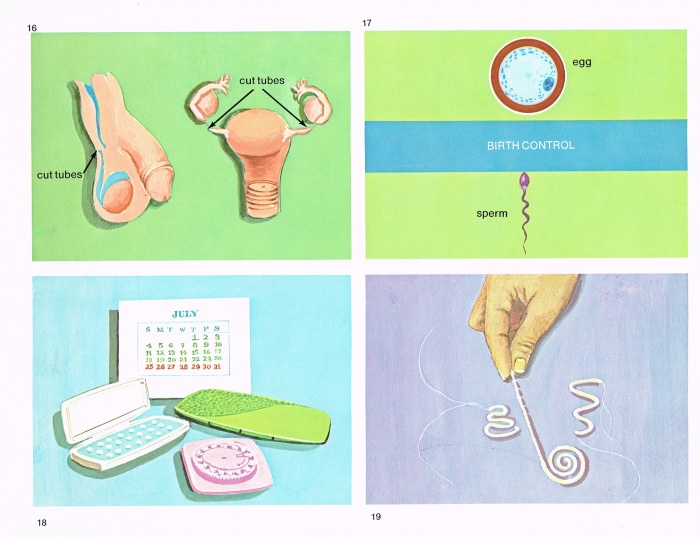

In the early 1970s, scores of liberated, fertile women were eager to join the sexual revolution. Along with the diaphragm and IUD, the recently available birth control pill gave women the autonomy to decide when and if they would have children. With so many options and the pill so new, where could a woman turn to get reliable advice and information about contraception? A gynecologist? A trusted female relative? How about an “educational” two-LP set produced by a fly-by-night operation whose only other output may have been a twelve cassette informational program for dental students?

In the early 1970s, scores of liberated, fertile women were eager to join the sexual revolution. Along with the diaphragm and IUD, the recently available birth control pill gave women the autonomy to decide when and if they would have children. With so many options and the pill so new, where could a woman turn to get reliable advice and information about contraception? A gynecologist? A trusted female relative? How about an “educational” two-LP set produced by a fly-by-night operation whose only other output may have been a twelve cassette informational program for dental students?

Enter You Don’t Have to Get Pregnant, produced by In Sight & Sound. Or maybe it’s Plan Your Family by Health Information Systems, Inc. Who’s to say? The record’s spartan label calls the set Plan Your Family, while the cover and accompanying booklet—both showing a couple embracing as they walk along the beach—include both proclamations. For what it’s worth, the Library of Congress (along with the University of North Texas, the only other institution with the set still cataloged) has chosen to catalog it as Plan Your Family, the single publication linked to In Sight & Sound. WorldCAT, a searchable network of libraries worldwide, does show other listings for Health Information Systems, Inc.: the set of instructional dental cassettes mentioned above and produced at roughly the same time as Plan Your Family (I’ll use this title going forward).

Whatever the set’s provenance, the creators of the LP were shockingly ill-equipped to advise women on options for their reproductive needs. Paternalism, racism, and outright misinformation pervade Plan Your Family, and it’s prime for aural rubbernecking. With availability of birth control only truly becoming legal nationwide via the Supreme Court’s Eisenstadt v. Baird ruling in 1972—following the more well-known Griswold v. Connecticut, which ensured access to birth control but did not supersede restrictive state laws in about half the country—the sudden need for birth control education may have been a call In Sight & Sound felt moved to answer. Their apparent decision to make Plan Your Family without consulting an OBGYN, however, is another issue entirely.

“Not Trusting to Luck. Not Depending on Hope”

“Not Trusting to Luck. Not Depending on Hope”

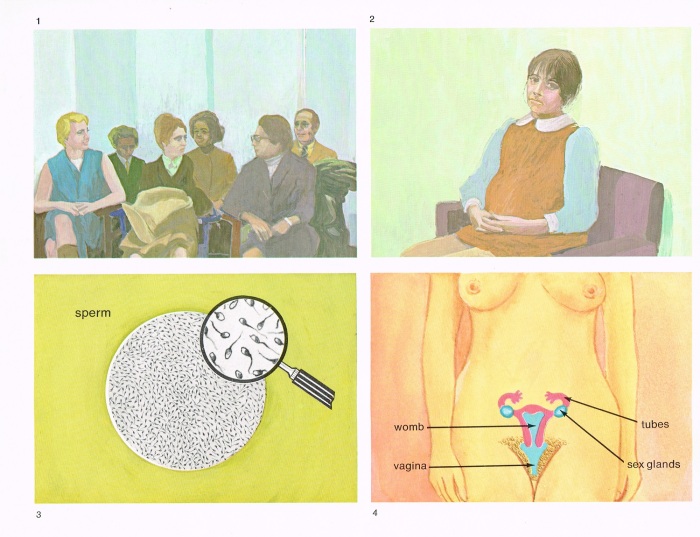

Plan Your Family may have rolled its listeners’ understanding of the female reproductive system back at least two decades. With no introduction other than a disembodied, paternalistic voice imploring us to listen as he addresses us “as a doctor would,” our unnamed narrator begins his four-sided slog. We’re asked to consult the first image in the record set’s accompanying booklet, showing a waiting room full of women—and men—seeking birth control. Our narrator relays his reasons to delay childbirth in a tangle of unattributed quotes. Some cite exhaustion, some cite expense. And one “frank single woman” tells us she “expect[s] to get married,” but doesn’t know when. Birth control is for “the meantime.”

Whatever trust and goodwill Plan Your Family gained in the waiting room is lost as we’re asked to move on to the next illustration. Here, we’re told, is someone who should employ birth control posthaste. A young woman, more olive-complected than most of the waiting room we just left, sits with downcast eyes. We’re told she has five other children, lives in a two-room apartment, and is pregnant. A pause. “Again.” Our narrator-cum-eugenicist doesn’t just hint that she might consider birth control, he expresses disdain that she hasn’t used it before.

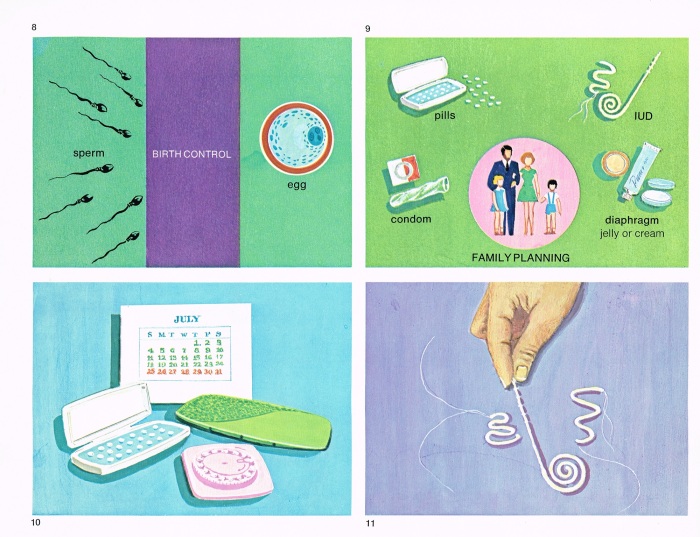

“How Does the IUD work? We Don’t Really Know”It’s just past the waiting room that Plan Your Family really tips its hand, letting us know it’s engaging in gynecological spitballing. Condensed to its basic information, Plan Your Family would run the side of one record. Condensed to accurate family planning advice, it would run even less. From the history of the IUD to the mechanics of the pill and to the very basics of ovulation, Plan Your Family is the equivalent of a book report written the night before, and it’s a wonder it was ever mass-produced.

Like all of the methods discussed, we’re introduced to the IUD—the “intra-utereen device”—on side one, and we revisit it with nearly identical wording later on. It’s this repetition that twice gives us the gem “”Exactly how does the IUD work? Doctors still aren’t sure.” In fact, the modern IUD had been in use for at least 20 years in 1972, and the idea of placing a foreign object into the uterus to prevent pregnancy dates back even farther.

“You Can Make Love Whenever You Want”The birth control pill is given one full side of Plan Your Family, but our narrator’s understanding of how the pill works is more than a little shaky. In the In Sight & Sound universe, the pill “prevents the production of eggs,” a phrase that seems to imply that women lay eggs like chickens. Women are born with all the eggs they will have in a lifetime, and what the birth control pill does is suppress ovulation—that is, keeps an egg from becoming available to be fertilized. The egg itself was “produced” at birth.

The rhythm, or calendar, method also gets the In Sight & Sound treatment. It’s described here as not only faulty (it is less reliable) but allowing conception-free sex only half the month. Unless our narrator is including the messy but not disqualifying business of menses in his tallies, in reality that number is only about five days to a week of each month. Even less if a woman is tracking her basal temperature—which our narrator mentions as a vital component of the rhythm method.

But what about men? Our listeners, presumably all female, are told “You are in control over your pregnancy. Not the man.” And in the United States in 1972, women did have an unprecedented level of autonomy in their family planning decisions. But In Sight & Sound acknowledges that “a man can do everything that needs to be done to keep a woman from becoming pregnant.” For example, withdrawal, which “isn’t much better than trusting to luck.” Condoms are somewhat creepily referred to as “good to use at special times.” Finally, sterilization, a “confusing and sometimes frightening word,” prevents a man from releasing sperm at all.

The Plan Your Family team still needed to do some padding to fill all four sides, so they combat schoolyard contraceptive myths: wrapping your penis in plastic wrap is not an adequate substitute for a condom. Douching will not expel sperm. And sex standing up—or in any position, for that matter—will not prevent pregnancy.

“The Answer is Probably”Who exactly was Plan Your Family meant for? My own copy, rescued from a community college dumpster in 2008, has the stamp of the college’s nursing program, assuredly a better resource to accurately instruct students about a woman’s family planning choices. Then again, without a way to sample content beforehand, it would have been impossible to know how condescending, ill-informed, and outright lazy the set was. Librarians don’t have the opportunity to sample every item they catalog. And so Plan Your Family languished on a library shelf for more than three decades, imbuing a thankfully minuscule number of junior college students with an alarmingly befuddled understanding of a woman’s reproductive system.

It’s a blessing that Plan Your Family wasn’t released a year later, when Roe v. Wade would have given In Sight & Sound a steeper mountain to climb—to the peril of any and all information seekers within earshot. Whether by a sincere desire to educate or because they had a contract to fulfill, In Sight & Sound—or Health Information Systems, Inc.—rallied to answer the call of women with questions about how to exercise their newly-won sexual autonomy. In the end, the project’s clumsy and misguided attempt to do right by women exists as an artifact of 1972’s acknowledgement of the sexual revolution, as well as the lack of tools and vocabulary needed to advance it.

![]() Lindsay Oxford writes about vegan food for Sacramento News & Review and writes personal essays at igetbored.pizza.

Lindsay Oxford writes about vegan food for Sacramento News & Review and writes personal essays at igetbored.pizza.

Last year I was contacted to work on a Yu-Gi-Oh! movie. Unfortunately it fell through because Frankie Muniz refused to play Yugi Muto.

Thats not true but check out this Blue Eyes White Dragon I painted.

WIP detail for a book I’ve been slowly working on for a while now. This is something I do in between projects so it’s probably going to take a few more months, but I’m hoping to get the whole thing completed next year. :)

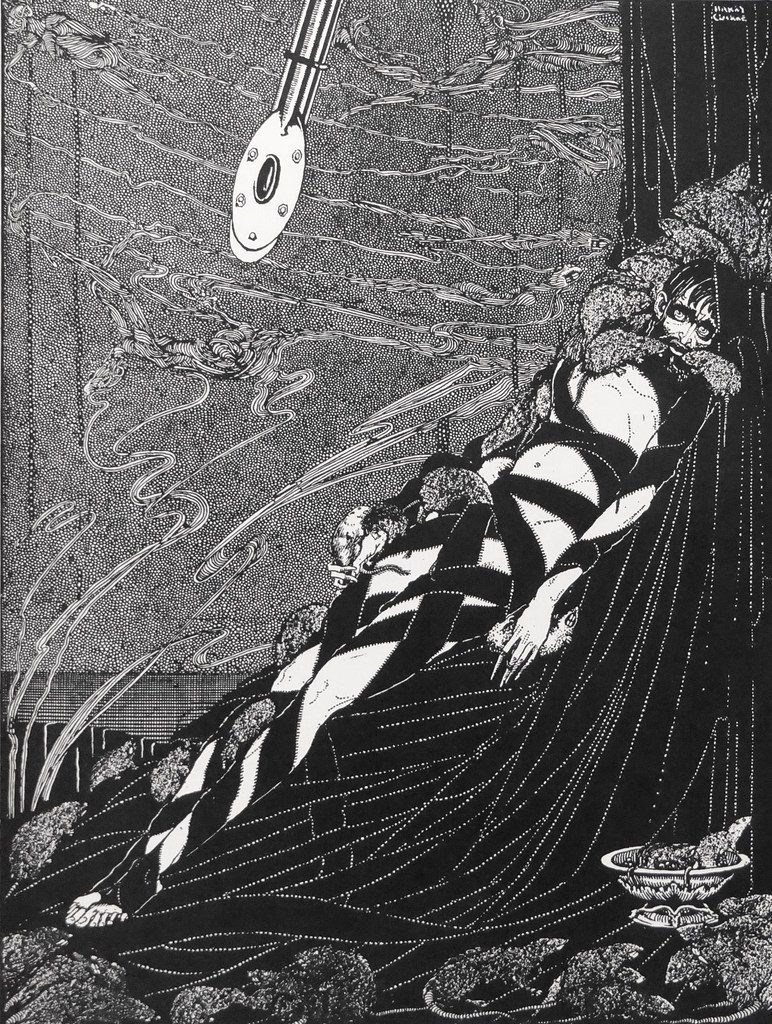

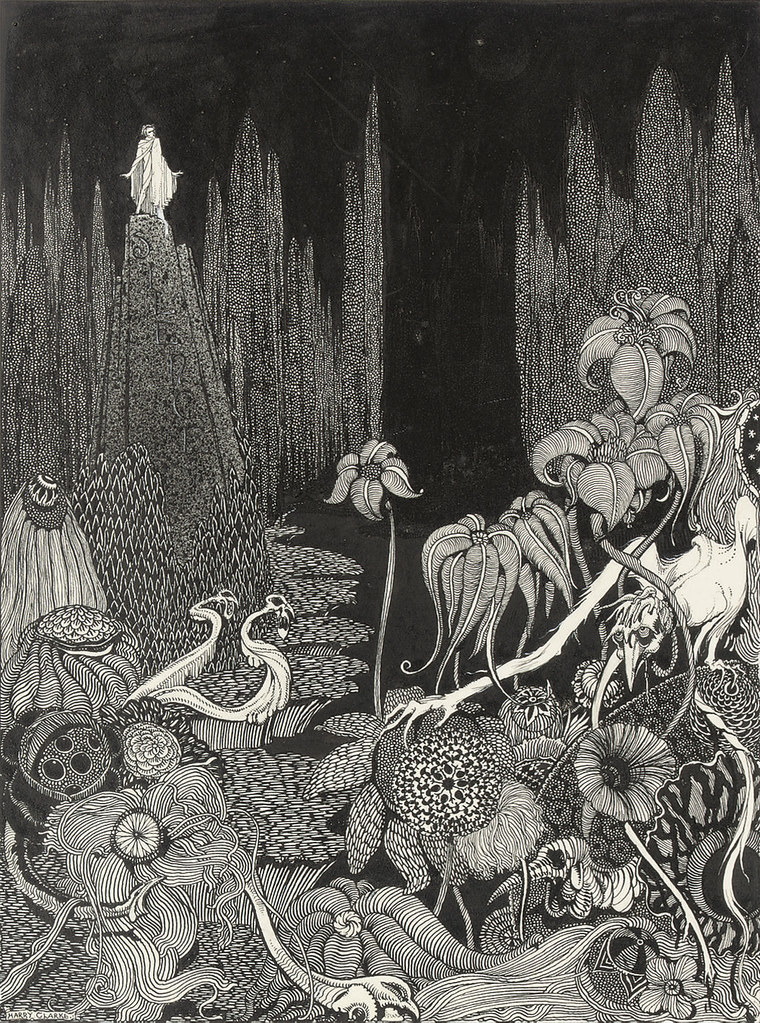

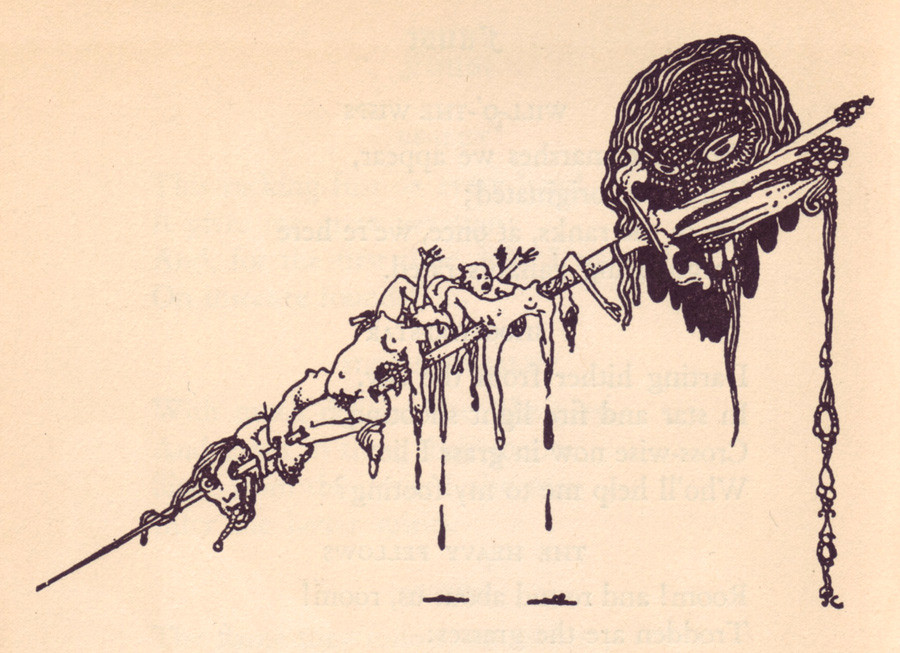

Interior art for Edgar Allan Poe's "Tales of Mystery and Imagination" (1936)

Interior art for Edgar Allan Poe's "Tales of Mystery and Imagination" (1936) "Say, rather, the rending of her coffin." Interior art for Edgar Allan Poe's Tale "The Fall of the House of Usher." (1936)

"Say, rather, the rending of her coffin." Interior art for Edgar Allan Poe's Tale "The Fall of the House of Usher." (1936) "It was the most noisome quarter of London." Illustration from Edgar Allan Poe's Tale "The Man of the Crowd"(1936)

"It was the most noisome quarter of London." Illustration from Edgar Allan Poe's Tale "The Man of the Crowd"(1936) "He shrieked once, once only." Art for Poe's "Tales of Mystery & Imagination" (1936)

"He shrieked once, once only." Art for Poe's "Tales of Mystery & Imagination" (1936) "An attachment which seemed to attain new strength." Art for Poe's Tale "Metzengerstein" (1936)

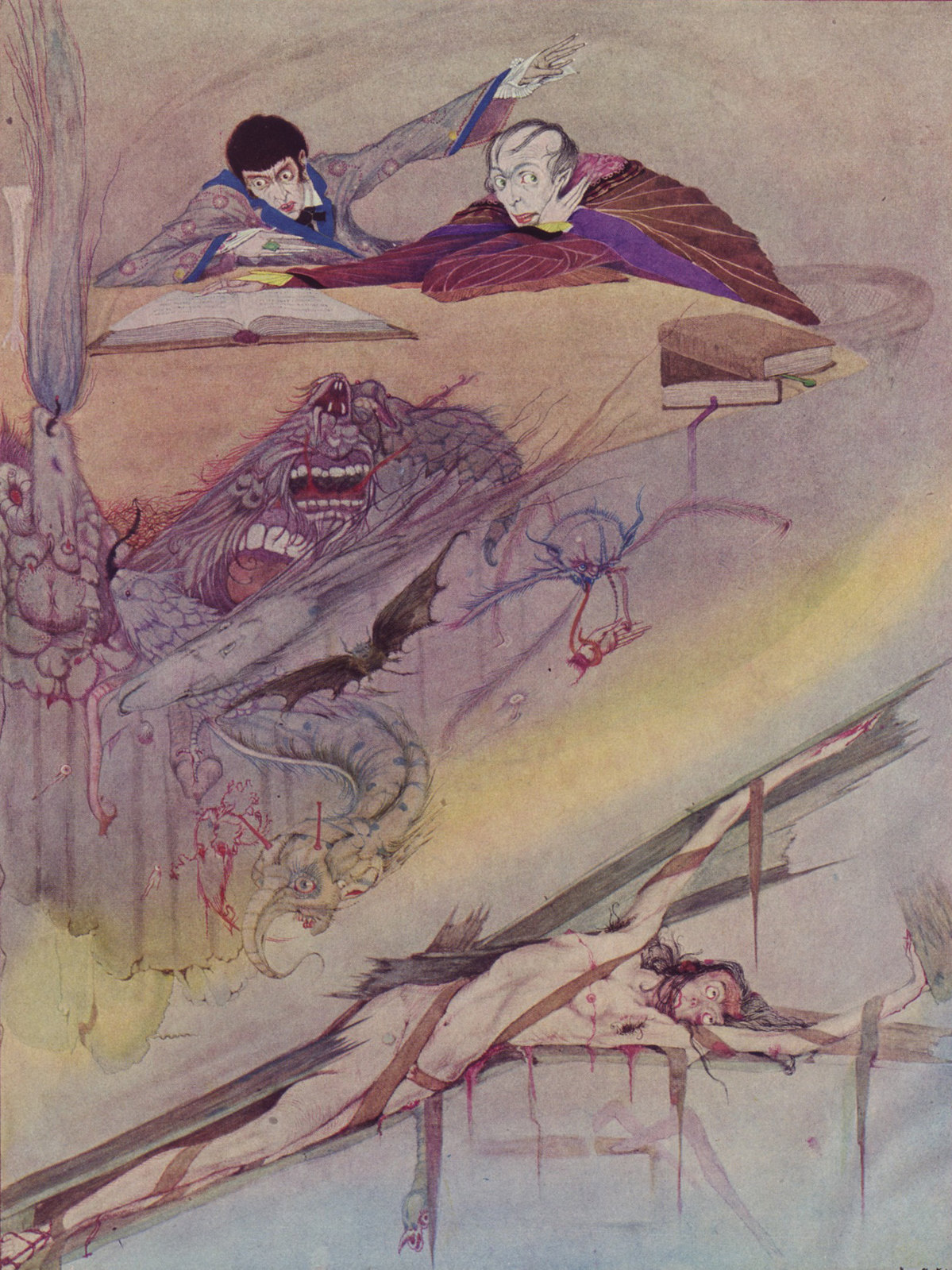

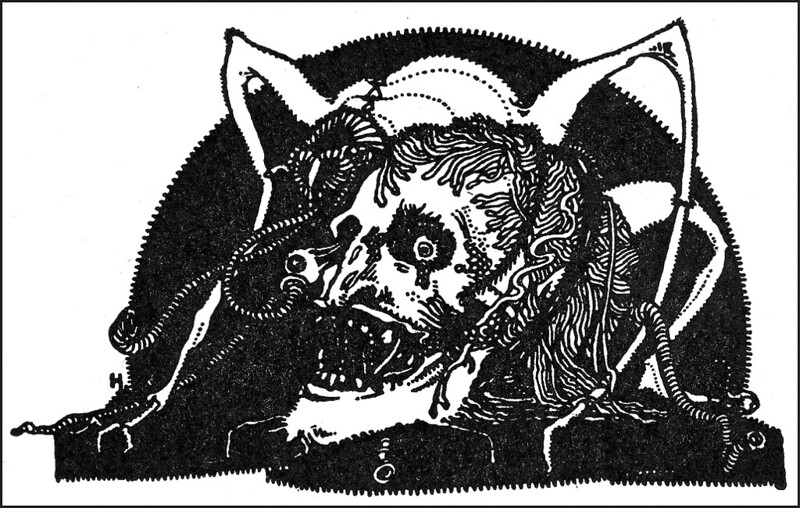

"An attachment which seemed to attain new strength." Art for Poe's Tale "Metzengerstein" (1936) "Gnashing its teeth and flashing fire from its eyes, it flew upon the body of the girl." Art for Poe's "The Murders in the Rue Morgue" (1936)

"Gnashing its teeth and flashing fire from its eyes, it flew upon the body of the girl." Art for Poe's "The Murders in the Rue Morgue" (1936) "The dagger dropped gleaming upon the sable carpet." Art for Poe's "The Pit and the Pendulum" (1936)

"The dagger dropped gleaming upon the sable carpet." Art for Poe's "The Pit and the Pendulum" (1936) "I had walled the monster up within the tomb!" Art for Poe's "The Black Cat" (1936)

"I had walled the monster up within the tomb!" Art for Poe's "The Black Cat" (1936) "It was a fearful page in the record of my existence." Art for Poe's Tale "Berenice." (1936)

"It was a fearful page in the record of my existence." Art for Poe's Tale "Berenice." (1936) "But, for many minutes, the heart beat on with a muffled sound." Art for Poe's "The Tell-Tale Heart" (1936)

"But, for many minutes, the heart beat on with a muffled sound." Art for Poe's "The Tell-Tale Heart" (1936) "They swarmed upon me in ever-accumulating heaps." Art for Poe's "The Pit and the Pendulum" (1936)

"They swarmed upon me in ever-accumulating heaps." Art for Poe's "The Pit and the Pendulum" (1936) Edgar Allan Poe's "Fall of the House of Usher", 1936

Edgar Allan Poe's "Fall of the House of Usher", 1936 "Deep, deep, and forever, into some ordinary and nameless grave." Art for Edgar Allan Poe's "The Premature Burial", 1936

"Deep, deep, and forever, into some ordinary and nameless grave." Art for Edgar Allan Poe's "The Premature Burial", 1936 Edgar Allan Poe's "Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar" 1936

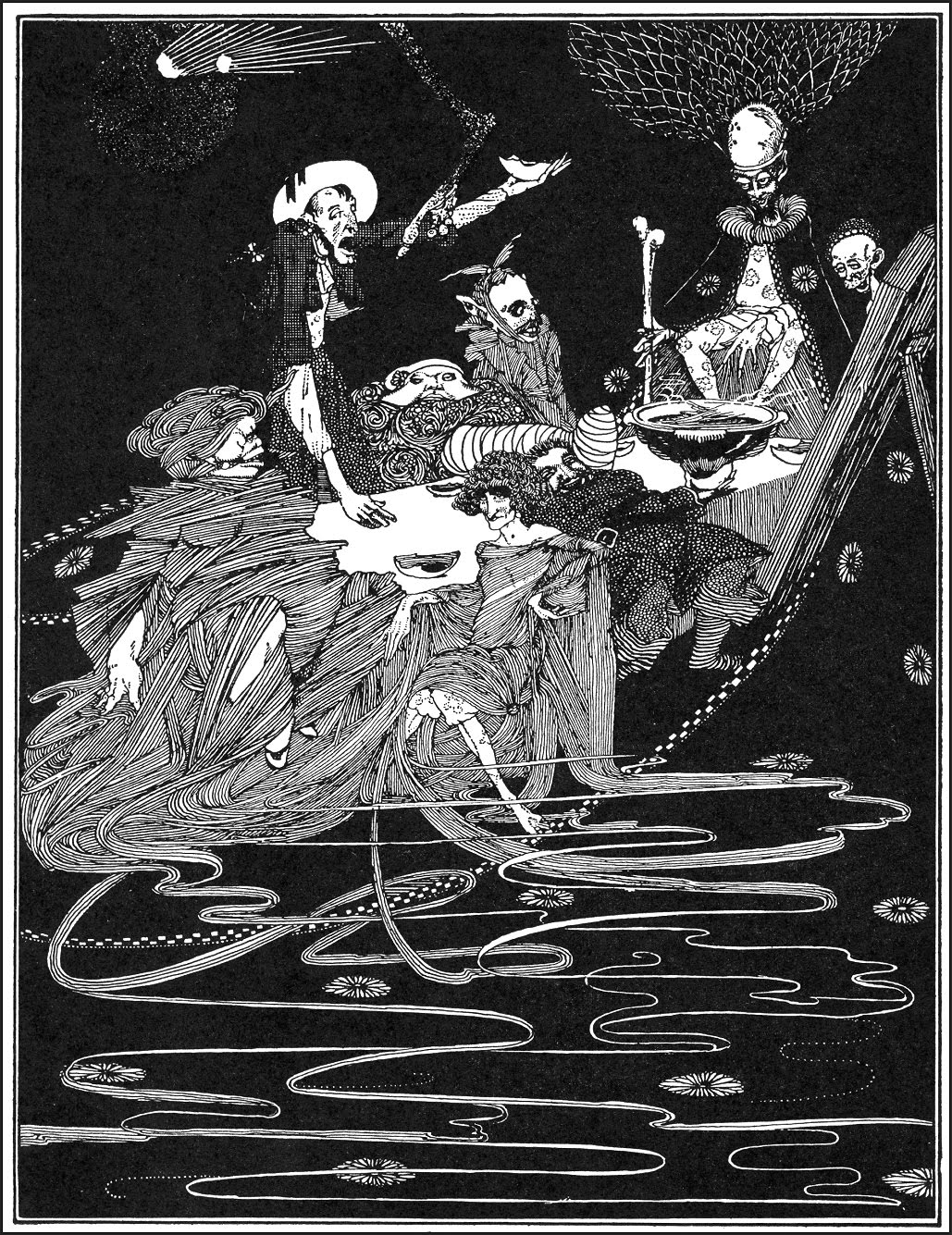

Edgar Allan Poe's "Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar" 1936 Edgar Allan Poe's "King's Pest", 1936

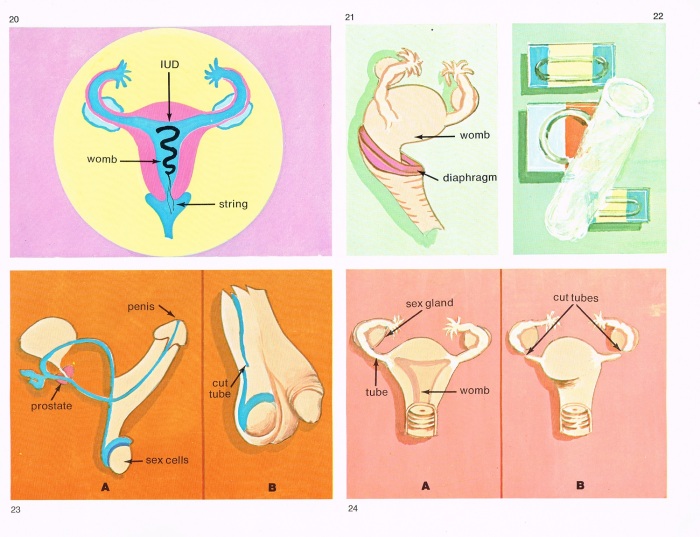

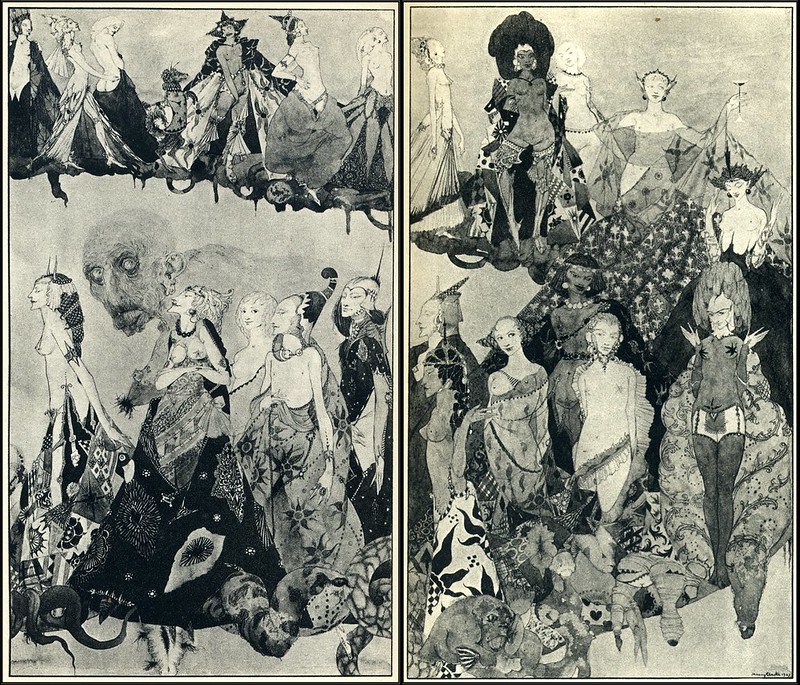

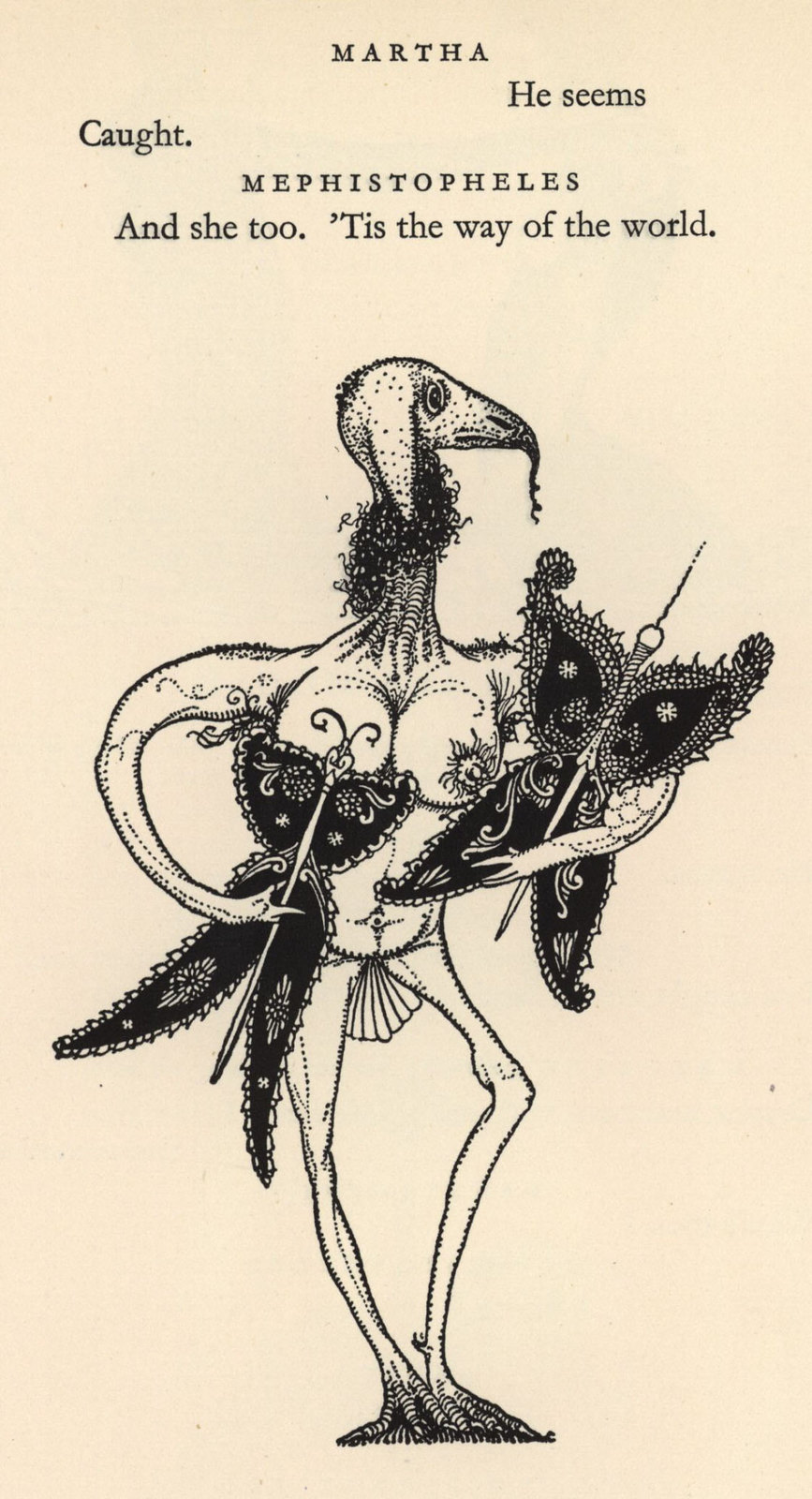

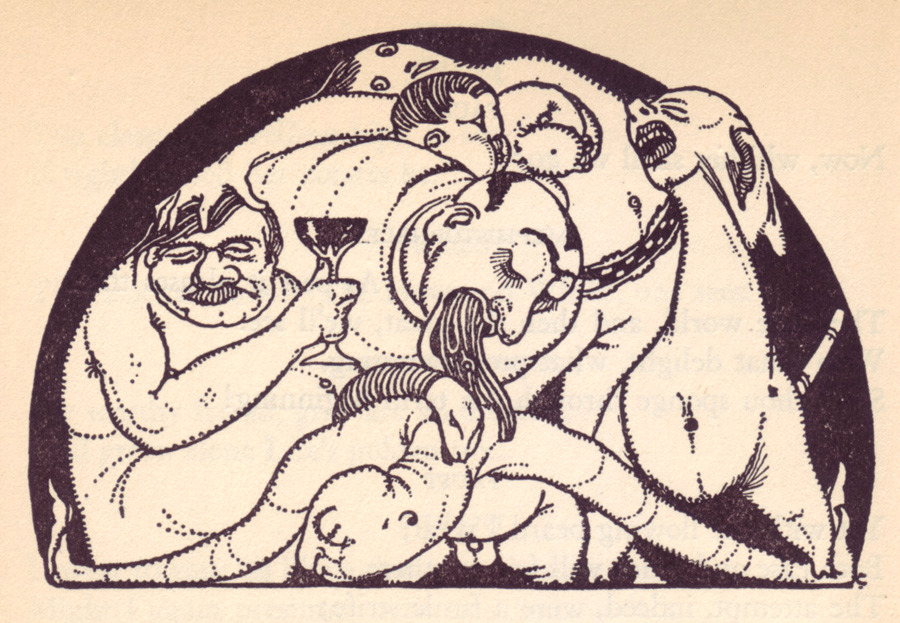

Edgar Allan Poe's "King's Pest", 1936 "Methinks, a million fools in choir are raving and will never tire." interior art for Goethe's Faust, 1927

"Methinks, a million fools in choir are raving and will never tire." interior art for Goethe's Faust, 1927 Margaret: "Drest thus, I seem a different creature!" Art for Goethe's Faust, 1927

Margaret: "Drest thus, I seem a different creature!" Art for Goethe's Faust, 1927 Mephistopheles: "Is there anything in my poor power to serve you?" Art for Goethe's Faust, 1927

Mephistopheles: "Is there anything in my poor power to serve you?" Art for Goethe's Faust, 1927 Siebel: "Clustering grapes invite the hand." Art for Goethe's Faust, 1927

Siebel: "Clustering grapes invite the hand." Art for Goethe's Faust, 1927 Mephistopheles: "Come - she is judged!" Art for Goethe's Faust, 1927

Mephistopheles: "Come - she is judged!" Art for Goethe's Faust, 1927 Mephistopheles: "Forward! forward! faster! faster!" Art for Goethe's Faust, 1927

Mephistopheles: "Forward! forward! faster! faster!" Art for Goethe's Faust, 1927 Illustration for Faust, 1925

Illustration for Faust, 1925

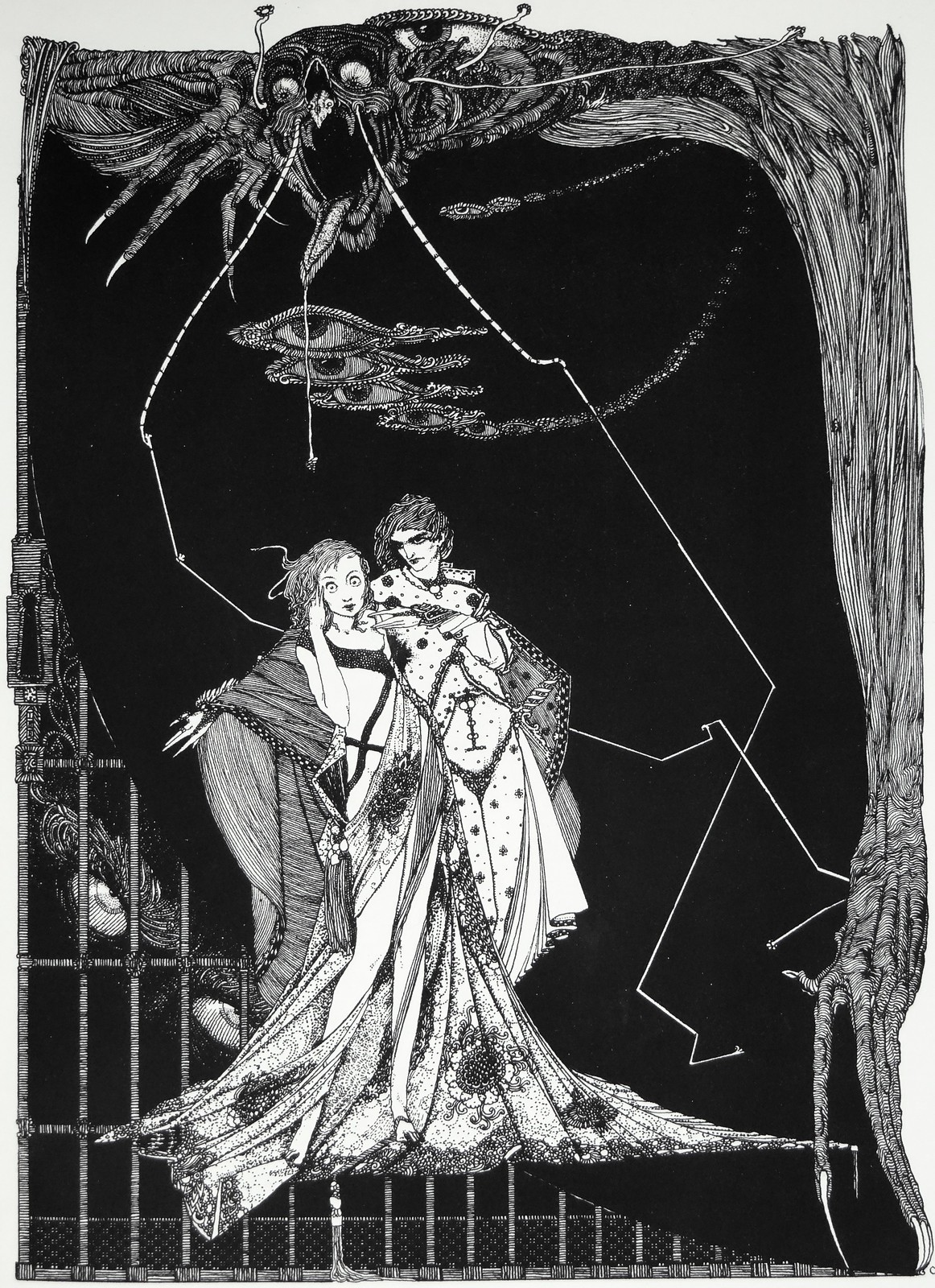

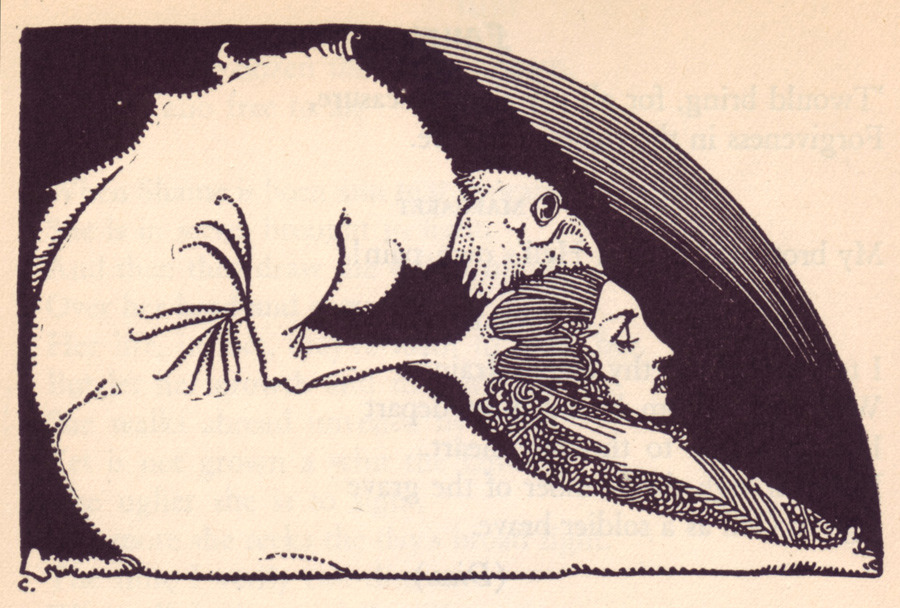

Margaret: "Does not death lurk without?" Art by Harry Clarke for Goethe's Faust (1927)

Margaret: "Does not death lurk without?" Art by Harry Clarke for Goethe's Faust (1927) Wizards and Warlocks: "On a road like this men droop and drivel, while woman goes fearless and fast to the devil." Art by Harry Clarke for Goethe's Faust (1927)

Wizards and Warlocks: "On a road like this men droop and drivel, while woman goes fearless and fast to the devil." Art by Harry Clarke for Goethe's Faust (1927) Tailpiece for Goethe's Faust (1927). Signed, Limited American Edition

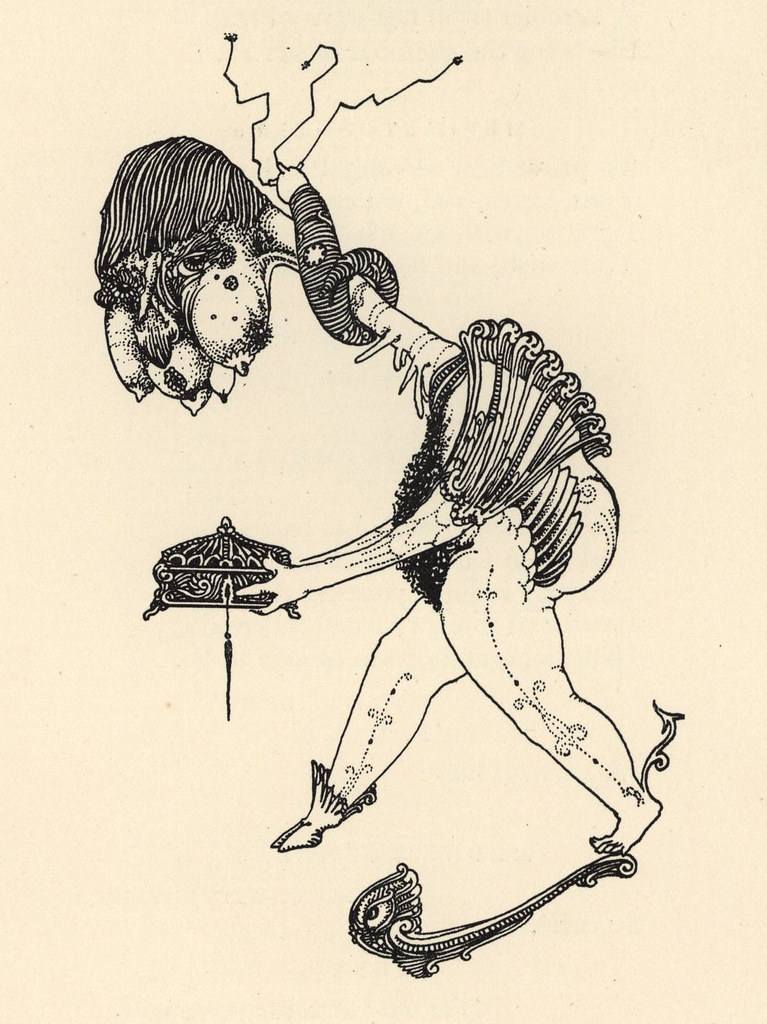

Tailpiece for Goethe's Faust (1927). Signed, Limited American Edition "How heavenly Fair the Form that shines: in this enchanted glass" interior art for Goethe's Faust, 1927

"How heavenly Fair the Form that shines: in this enchanted glass" interior art for Goethe's Faust, 1927

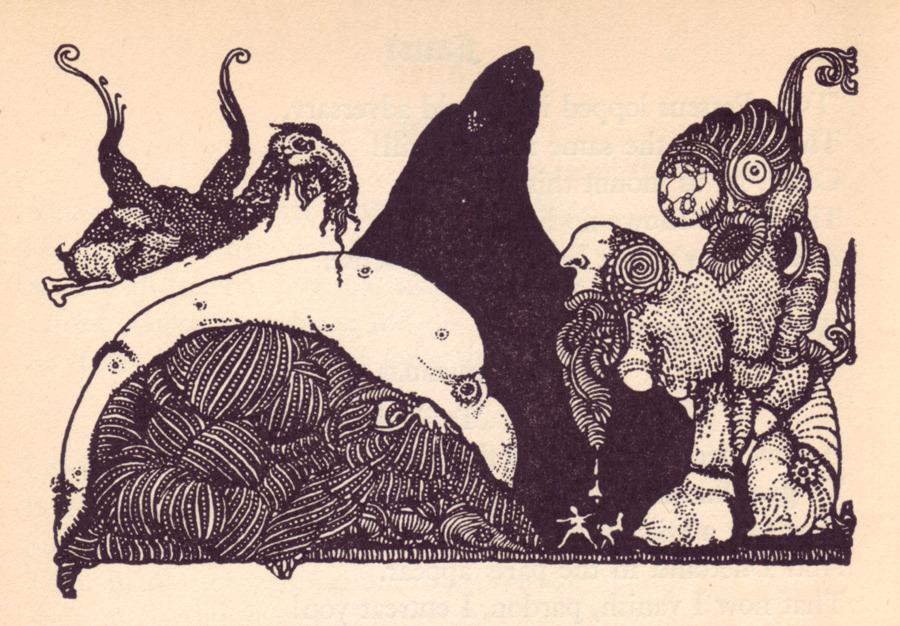

"Let him have his head cut off!"From "The Traveling Companion" from Hans Christian Andersen's Fairy Tales, 1916

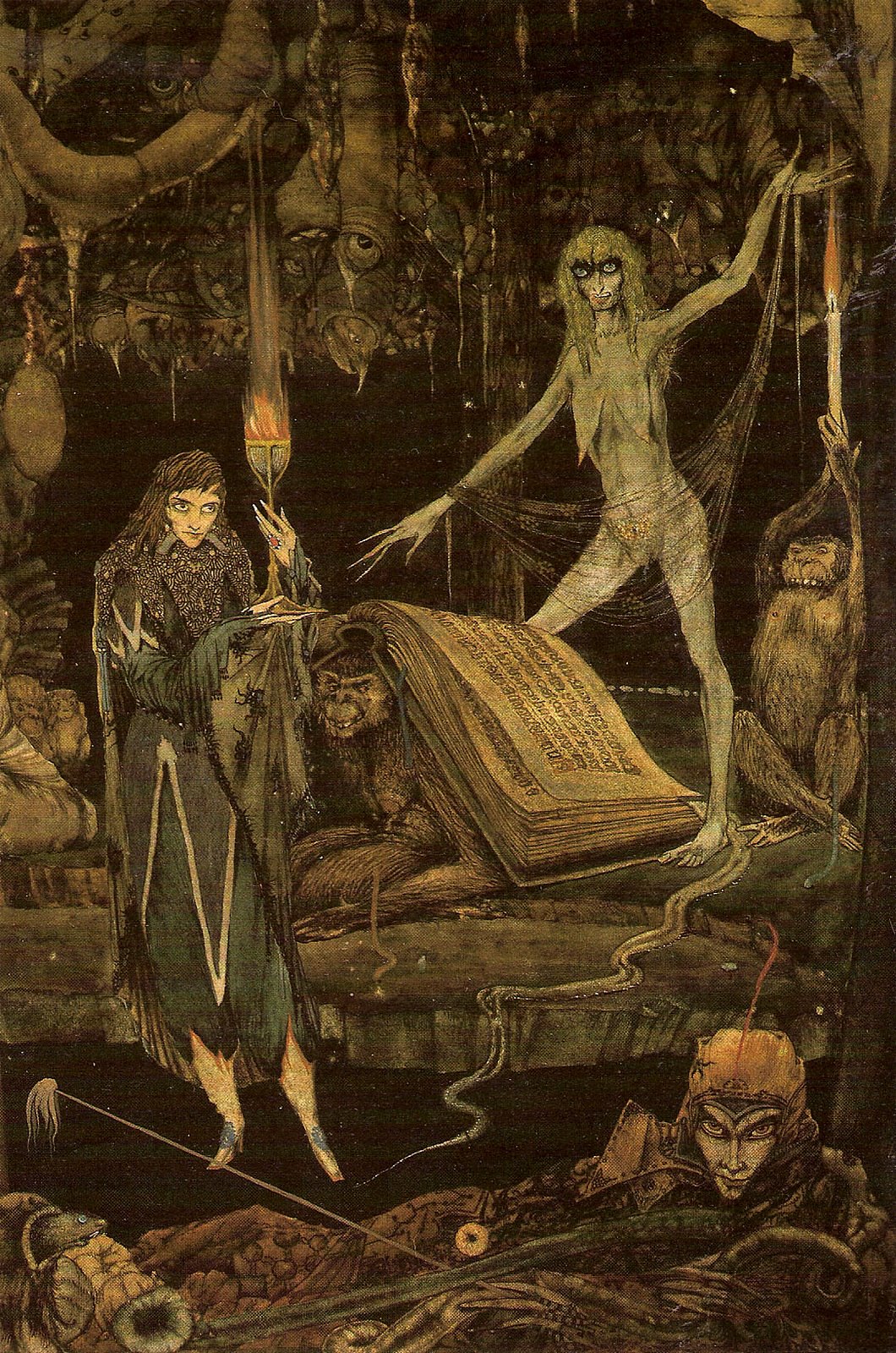

"Let him have his head cut off!"From "The Traveling Companion" from Hans Christian Andersen's Fairy Tales, 1916 “‘I know what you want,’ said the sea witch." Illustration from "The Little Sea Maid," Fairy Tales by Hans Christian Andersen, 1916

“‘I know what you want,’ said the sea witch." Illustration from "The Little Sea Maid," Fairy Tales by Hans Christian Andersen, 1916 "How do you manage to come on the great rolling river?"From "The Snow Queen" from Hans Christian Andersen's Fairy Tales, 1916

"How do you manage to come on the great rolling river?"From "The Snow Queen" from Hans Christian Andersen's Fairy Tales, 1916 "'Music! Music!' cried the Emperor. 'You little precious golden bird, sing!'" From "The Nightingale" from Hans Christian Andersen's Fairy Tales, 1916

"'Music! Music!' cried the Emperor. 'You little precious golden bird, sing!'" From "The Nightingale" from Hans Christian Andersen's Fairy Tales, 1916 "'But how will I find the money?' asked the soldier."From "The Tinder Box," from Hans Christian Andersen's Fairy Tales, 1916

"'But how will I find the money?' asked the soldier."From "The Tinder Box," from Hans Christian Andersen's Fairy Tales, 1916 "'Don't give yourself airs,' said the old man."From "The Elf Hill" from Hans Christian Andersen's Fairy Tales, 1916

"'Don't give yourself airs,' said the old man."From "The Elf Hill" from Hans Christian Andersen's Fairy Tales, 1916 Silence

Silence Illustration from Selected Poems of Charles Swinburne, 1928

Illustration from Selected Poems of Charles Swinburne, 1928 Art for the Poem "The Leper" by Harry Clarke in "Selected Poems of Algernon Charles Swinburne" (1928)

Art for the Poem "The Leper" by Harry Clarke in "Selected Poems of Algernon Charles Swinburne" (1928) Art for the Poem "Faustine" by Harry Clarke in "Selected Poems of Algernon Charles Swinburne" (1928)

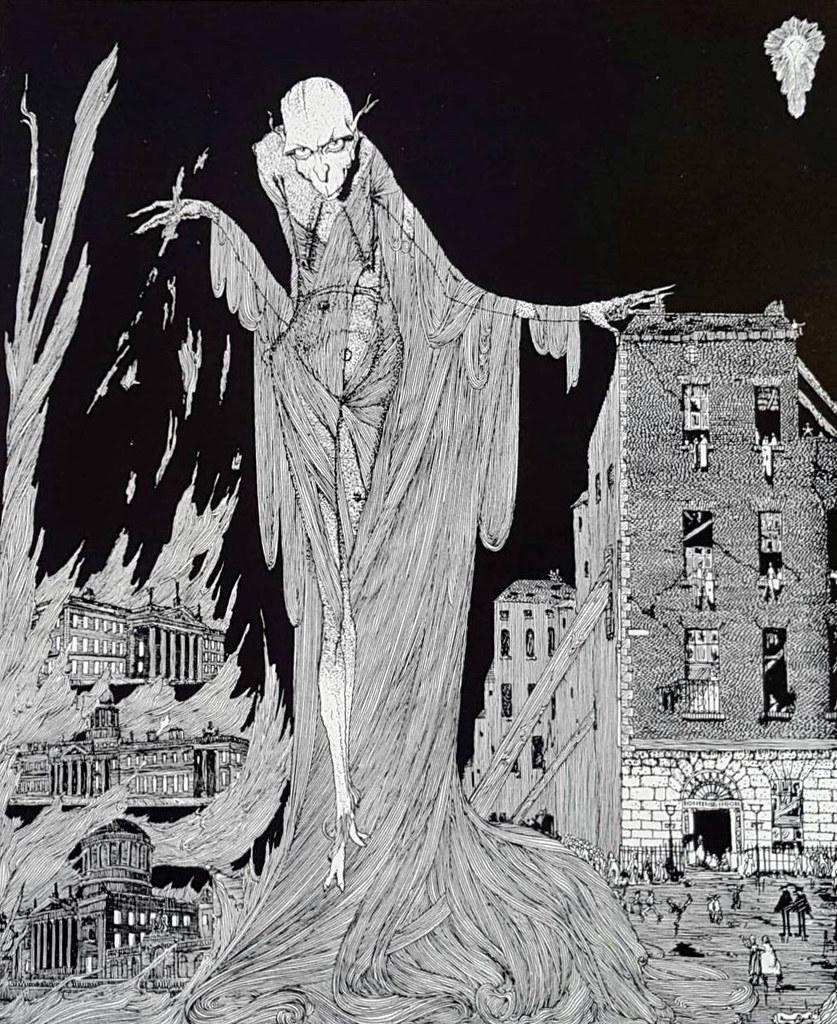

Art for the Poem "Faustine" by Harry Clarke in "Selected Poems of Algernon Charles Swinburne" (1928) "The Last Hour of the Night," illustration for Dublin of the Future, 1922

"The Last Hour of the Night," illustration for Dublin of the Future, 1922 Judith slaying Holofernes, early 20th C

Judith slaying Holofernes, early 20th C Harry Clarke - Mephistopheles, for "Faust" by Goethe, 1925

Harry Clarke - Mephistopheles, for "Faust" by Goethe, 1925

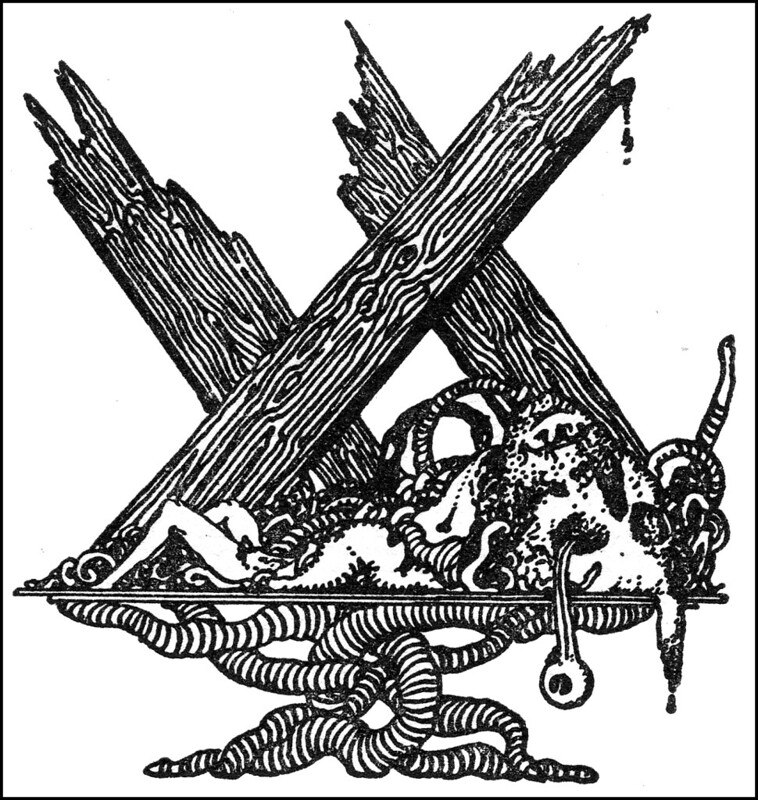

Decoration in "Faust" by Goethe, 1925

Decoration in "Faust" by Goethe, 1925 Decoration in "Faust" by Goethe, 1925

Decoration in "Faust" by Goethe, 1925 Decoration in "Faust" by Goethe, 1925

Decoration in "Faust" by Goethe, 1925 Decoration in "Faust" by Goethe, 1925

Decoration in "Faust" by Goethe, 1925 Decoration in "Faust" by Goethe, 1925

Decoration in "Faust" by Goethe, 1925 Interior art from Edgar Allan Poe's "Tales of Mystery and Imagination" 1923

Interior art from Edgar Allan Poe's "Tales of Mystery and Imagination" 1923 Interior art from Edgar Allan Poe's "Tales of Mystery and Imagination" 1923

Interior art from Edgar Allan Poe's "Tales of Mystery and Imagination" 1923 Interior decoration from Selected Poems of Charles Swinburne, 1928

Interior decoration from Selected Poems of Charles Swinburne, 1928 Interior decoration from Selected Poems of Charles Swinburne, 1928

Interior decoration from Selected Poems of Charles Swinburne, 1928Exhibit / November 21, 2019

Object Name: The Georgia Guidestones

Maker and Year: The Elberton Granite Finishing Co., Inc., 1981

Object Type: Promotional publication

Image Source: Wired.com

Description (Michael Grasso):

On the vernal equinox in 1980, a group of local dignitaries gathered on a ridgetop near Elberton, Georgia, to witness the dedication and unveiling of a monument made of six colossal slabs of Georgia blue granite. The Georgia Guidestones have remained the center of a firestorm of controversy in the nearly four decades since their unveiling, while simultaneously becoming an object of great local civic pride. The Guidestone monoliths contain a series of ten “commandments” for distant human posterity, an inscription dedicated to the moral and material health of humanity in twelve languages—four ancient, eight modern—in the face of then-current issues such as overpopulation, nuclear holocaust, and environmental pollution. The real story behind these modern-day standing stones—primarily, who exactly commissioned and designed them—is cloaked in mystery and misdirection to the present day. This mystery was only intensified by the publication of a 48-page pamphlet (full document here) in 1981 by the granite company behind the Guidestones’ physical construction. The pamphlet combines a “how did they do it” explainer with interpretations of the Guidestones’ mysterious inscriptions. But The Georgia Guidestones booklet also lays bare some of the tensions between a rural Georgia community and the attention that this eccentric outsider art project-cum-social statement brought to the area.

The booklet was produced by the management of the local stoneworkers who created the physical stones, the Elberton Granite Finishing Company, Inc. On the very first page, in the booklet’s foreword, the company openly admits that the messages on the stones will prove “intriguing,” “provocative,” “significant,” and that “not everyone will agree with all of the succinct ‘guides’ which have been permanently inscribed… in these massive pieces of Elberton Granite.” How did this small town receive such a daunting and strange task? The booklet pens a narrative about Joe Fendley, president of the granite company, receiving a “neatly dressed” visitor on a June Friday in 1979, asking for the company to build him a monument. This visitor, named R. C. Christian, “represented a ‘small group of loyal Americans who believe in God… [who wished to] leave a message for future generations.'” When Christian backs up his words with the real American language—cold hard cash brought to the bank by Christian’s lawyer, banker, and “intermediary” Wyatt C. Martin—the locals, according to the pamphlet, realized that the project was no prank.

This origin narrative is—by design, one assumes—full of intentional mystery and symbolism. It also echoes two esoteric myths with deep roots in Western hermeticism and occult conspiracy. First, there is R.C. Christian’s name, which evokes the rich and centuries-old mythology surrounding Rosicrucianism, with its key founding documents detailing the occult journeys of a young magus named Christian Rosenkreuz (Rose Cross, R. C.). The tale of R.C. Christian’s mysterious arrival also echoes an American myth about a stranger named “the Professor” who was allegedly present among the Founding Fathers during the design of the American flag. This tale was first recorded in an 1890 book called Our Flag by Robert Allen Campbell and eventually given new life in 1940 by American esotericist Manly P. Hall. These two seemingly-disparate threads of American esotericism—the occult wisdom of secret societies and a sort of mystical American patriotism—intertwine freely throughout The Georgia Guidestones pamphlet, as the authorial voice continues to hammer home the message from the Foreword: that however bizarre, occult, and eerie the message of the Guidestones project might be, we are always assured that it is being directed by American patriots who believe in God.

The ten-part Guidestones message itself is explained directly by “the mysterious sponsors behind The Georgia Guidestones®” (whenever “The Georgia Guidestones” appears in the pamphlet, it is accompanied by a registered trademark symbol, which seems to betray the commercial intentions of the document quite clearly) in a five-page essay called “The Purpose.” The inscriptions call quite clearly for a radical population reduction (to a mere 500 million people worldwide; in 1980 the global population was already nearly 4.5 billion), for humanity to “guide reproduction wisely, improving fitness and diversity,” and for a universal human language and a new respect for nature. The sinister first pair of commandments have more than a whiff of old-fashioned American eugenics, which, along with the command for a universal language, would certainly raise alarm bells in socially-conservative late-1970s Georgia. In the very first paragraphs of “The Purpose,” the makers cite a need for “a global rule of reason” and “a rational world society,” two harbingers of the kind of one-world government that had long frightened postwar American arch-conservatives.

The language of “The Purpose” echoes much of the discourse in the 1970s about a New Age arriving, and asserts that humanity is finally ready for such an advancement: “Human reason is now awakening to its strength.” This concept of a planet mature enough to usher in a one-world government, thanks to achievements in reason and science, is a common narrative element in much of Cold War UFO lore. The specter of nuclear annihilation hovers over “The Purpose” as the main threat to humanity’s advancement; “The Purpose” clearly implies that the Guidestones’ message offers “alternatives to Armageddon.” Building a resilient time capsule for the future, one that could survive both the aeons and the possibility of nuclear or climate catastrophe, was evidently a major consideration in the physical design and construction of the Guidestones (echoing the work that would be done in think tanks in the next decade to design monuments to protect nuclear waste from future generations’ curiosity).

“The Purpose” spends nearly two pages defending its population control policy from common political, cultural, and religious objections. Concerns about overpopulation were very timely in the 1970s: the the Club of Rome‘s report The Limits to Growth was published in 1972, and a constant theme throughout popular culture and media throughout the 1970s was an overpopulated and underfed future. The makers of the Guidestones propose that reproduction and parenting be “regulated”: “The wishes of human couples are important, but not paramount.” Coincidental in 1979 with the Georgia Guidestones project was the introduction of the People’s Republic of China’s “one-child policy,” which follows the hopes of “The Purpose” that “every national government develop immediately a considered ‘Population Policy’,” which would “take precedence over other problems, even those relating to national defense.” Later on within the booklet, an “independent” interpretation of the Guidestones’ message is provided by one Dr. Francis Merchant, a local Elberton citizen and English Ph.D. who died after the erection of the monuments but before the publication of the booklet. His assessments are more matter-of-fact than those of “The Purpose,” but take into consideration the cultural and political changes that would be necessary to live up to the aspirations of the Guidestones (along with dropping a tantalizingly Masonic reference or two: deeming God to be “the Great Architect,” for example).

Throughout The Georgia Guidestones, it’s unclear how much of all these varying explanations and interpretations are merely good old-fashioned carnival kayfabe meant to intrigue visitors and collect tourist dollars. A perhaps uncharitable reading of the booklet would be that the entire cast of characters who take credit for different elements of the Guidestones project—Fendley, Martin, and Merchant, among others—were themselves R.C. Christian. The images of Fendley’s laborers working on giant slabs of Georgia granite throughout the pamphlet make it clear that the project was an enormous physical undertaking for the workers involved (and yet it was all completed in a little under nine months, if the story in The Georgia Guidestones is true). The booklet tells a story about one of the crew hearing “strange music and disjointed voices” while working on the inscriptions: more kayfabe perhaps, but also telling in that the makers of the Guidestones didn’t want the project’s mystical aura to stop at the money-and-idea men at the top. Again, a cynical reading of all the attention given to the actual quarry personnel, granite craftspeople, construction workers, and other expert laborers depicted in this booklet would be that Fendley wanted The Georgia Guidestones to act as a long-form advertisement for his company and for the granite industry of northeast Georgia at large. But with every photo offering a candid glimpse of the work and workers involved, the reader gains an appreciation for the fact that a large part of this tiny Georgia community was deeply involved in this project, a folly driven by seemingly mysterious fringe concerns, but one which touched almost everyone in the Elberton area. As with other weird municipal art projects elsewhere in 1970s America, Elberton seemed to embrace their Guidestones purely as quirky roadside attraction, another quintessentially 20th century American cultural tradition.

The Guidestone sponsors and Christian “himself” each directly lament the fact that ancient monuments like Stonehenge offer no concrete message to the modern world, that the true motivation for their construction and use, aside from their obvious calendrical and astronomical purposes, is unknown to us. With the purportedly “complete” picture of the process of making this monument, from conception to execution, The Georgia Guidestones booklet offers a vital gloss on the stones’ pure physical presence and their encoded message. It also offers a portrait of a small rural community in 20th century America at the end of arguably the nation’s Weirdest decade, a decade where issues of global survival met with the parochial concerns of post-industrial labor and production, filtered through a prism of the esoteric mysticism at the center of the entire American experiment.

Exhibit / November 20, 2019

Object Name: Aquarian Tarot Deck

Maker and Year: David Palladini, Morgan Press, 1970

Object Type: Tarot Cards

Image Source: Graphicine

Description: (Richard McKenna)

With their autumnal hues and deft fusion of the geometries of Art Nouveau and Art Deco, the tarot cards illustrated by David Palladini and published in 1970 by Morgan Press evoke perfectly the fading glow of the previous decade’s psychedelic optimism. The drift of interest in the esoteric and occult from the counterculture into the mainstream had been underway for some time: three years previously, Palladini had contributed to another pack of Tarot cards for Massachusetts paper producer Linweave and produced a series of Zodiac posters for Morgan Press. As well as Nouveau and Deco, Palladini’s style took inspiration from “decadents” like Harry Clarke and Aubrey Beardsley, the washed-out exoticism of illustrator Arthur Rackham, and even the expressionism of Munch, all filtered through memories of the early days of cinema and the poster art of the 1960s to create something that still looks modern today.

Palladini, who passed away in 2019, may be familiar from his illustrations for books like Jane Yolen’s 1974 book The Girl Who Cried Flowers and Other Tales, the 1987 edition of Stephen King’s The Eyes of the Dragon, and his remarkable, haunting poster for Werner Herzog’s 1979 Nosferatu. As his name suggests, Palladini came from an archetypal Italoamerican background—born in Italy in 1946, his family had emigrated to the United States in 1948 and settled in Illinois. After graduating from New York’s prestigious Pratt Institute Art School, which he attended on a scholarship, Palladini accepted a job as a photographer at the 1968 Mexico City Olympic Games. When the the chief poster designer abruptly departed, Palladini took over his post, creating a series of posters for the event. Once the Olympics were over, Palladini moved back to New York and took up a position with Push Pin Studios, then considered one of the most innovative illustration companies in the world.

As an illustrator working in the New York of the 1960s and ’70s, it seems likely that Palladini would have been moving in the same circles as British illustrator Peter Lloyd, who would later work on the production design of 1982’s Tron. Looking now at these monochrome faces in their glowing geometric garments, it’s hard to avoid the conclusion that Lloyd and/or the other production designers of Tron must have been familiar with Palladini’s work. Shortly before Tron‘s release, echoes of the elegiac formalism of Palladini’s Tarot were also to be found in the uncharacteristically restrained artwork the brilliant Bob Pepper produced for this set of Dragonmaster cards in 1981: both packs channel an entire history of Western art from the Middle Ages on into beautifully cohesive imaginary worlds. And as these cards by Suzanne Treister show—published 48 years after the publication of Palladini’s deck—Tarot continues to enjoy a position of importance in the countercultural pantheon.

Pepe Tesoro / November 19, 2019

Thomas Pynchon’s 1966 novel The Crying of Lot 49 is usually regarded as one of the best testimonies of Cold War paranoia and early psychedelic ’60s culture. Even though it is a keen and pointed exploration of the growing anxieties over the exponential post-war rise of mass media and market capitalism, the central conspiracy revealed in the novel doesn’t reproduce itself through the then-new and fascinating forces of radio waves or cathode rays. Quite the opposite: the kernel of the conspiracy in Pynchon’s novel lays precisely in a clandestine communication network sent through old-fashioned, conventional mail. This network itself possesses roots that go back as far as medieval nobility feuds, its presence identified with something as ancient and basic as graffiti. Fredric Jameson attributed the true effectiveness of the novel to this anomalous feature. “[T]he force of Pynchon’s narrative,” he writes in The Geopolitical Aesthetic: Cinema and Space in the World System, “draws not on the advanced or futuristic technology of the contemporary media so much as from their endowment with an archaic past.”

Thomas Pynchon’s 1966 novel The Crying of Lot 49 is usually regarded as one of the best testimonies of Cold War paranoia and early psychedelic ’60s culture. Even though it is a keen and pointed exploration of the growing anxieties over the exponential post-war rise of mass media and market capitalism, the central conspiracy revealed in the novel doesn’t reproduce itself through the then-new and fascinating forces of radio waves or cathode rays. Quite the opposite: the kernel of the conspiracy in Pynchon’s novel lays precisely in a clandestine communication network sent through old-fashioned, conventional mail. This network itself possesses roots that go back as far as medieval nobility feuds, its presence identified with something as ancient and basic as graffiti. Fredric Jameson attributed the true effectiveness of the novel to this anomalous feature. “[T]he force of Pynchon’s narrative,” he writes in The Geopolitical Aesthetic: Cinema and Space in the World System, “draws not on the advanced or futuristic technology of the contemporary media so much as from their endowment with an archaic past.”

It would seem that in order to perform an adequate exploration of the psychological and social and political disruptions of an era’s newest and most cutting-edge technological developments, sometimes it is required to take one or two steps back, as if the reflection over contemporary objects would be better served through the examination of old and already familiar realities. The long history and deep cultural footprint of retro-futuristic aesthetics in Pynchon’s fictional universe seems to point in somewhat the same direction. But this odd narrative movement doesn’t just go backwards; it also, quite interestingly, usually goes downwards. That’s the case of the The Crying of the Lot 49, where the occult conspiracy that our poor protagonist, Oedipa Maas, struggles to unveil, doesn’t just rely on the old means of the mail. Its members are imagined as marginalized individuals living in between the remnants and scraps of industrial machinery, as if the life of the vagabond would be the only true escape from the madness of modern civilization. These elusive individuals, as imagined by Oedipa, seem to be:

…squatters who stretched canvas for lean-tos behind smiling billboards along all the highways, or slept in junkyards in the stripped shells of wrecked Plymouths, or even, daring, spent the night up some pole in a lineman’s tent like caterpillars, swung among a web of telephone wires, living in the very copper rigging and secular miracle of communication, untroubled by the dumb voltages flickering their miles, the night long, in the thousands of unheard messages.

This supposed conspiracy of the homeless and the outcast, not subtly named W.A.S.T.E., is then imagined as a hidden net that mimics modern global communication networks, and even lives as close as it can to those hardware channels. And precisely because of that, it stays totally untouched by modernity and is invisible to its gaze. The particular mixture of secrecy, homelessness, and clandestine communication systems in Oedipa’s imagination was not new at the time, and can be traced back to the life and especially the works of one Leon Ray Livingston.

Livingston, born in 1872, was probably the most notorious American hobo. “Hobo“ is actually a rather particular term in American cultural history; it doesn’t merely designate an individual who lacks a stable location or place for living, but it instead indicates a quite idiosyncratic American social character, determined by the country’s own history of geographical expansion and industrialization. The hobo was a homeless man that crossed the entire continent, from city to city, throughout the growing railroad’s network, surfing the new, blossoming industrial landscapes a job at a time. Throughout the years, the hobo came to be recreated by the national cultural imagination as a romantic figure, a mystical outsider, a mysterious and almost invisible inhabitant of the modern world’s new industrial features, constantly at the edge of society, always trying to avoid unwelcome company and harassing authorities. That popular image was mostly the work of Livingston.

Livingston was not just a hobo; he was also a popular author. Under the pen name of “A-No1,” he published a series of books that fictionalized the hobo lifestyle and basically created from scratch the romantic and enigmatic portrait just described. But probably the most fascinating and persistent myth that emerged from the A-No1 books was the existence of a secret hobo code, presented in unnoticed and almost invisible chalk or charcoal graffiti. This code, composed of cryptic, seemingly ordinary and almost-childish hieroglyphs and symbols, was supposedly used by traveling hobos to transmit messages to their colleagues, such as “Dangerous town,” “Safe place to spend the night,” or “Here lives a nice lady.” It is known and well-documented (mostly through the work of filmmaker Bill Daniel) that the practice of signing the side of wagons and rail post with their personal monikers was and still is a spread practice for hobos and railroad workers in America. But with respect to a secret code that transmitted useful messages from hobo to hobo, there is not much evidence that it actually existed. After all, why would the hobo, a supposedly elusive and off-the-grid character, want to make public their own secret means of communication? It is not unfair to assume that the publication of the hobo code was probably nothing more than a ploy to fabricate and maintain that same legendary elusiveness.

Livingston was not just a hobo; he was also a popular author. Under the pen name of “A-No1,” he published a series of books that fictionalized the hobo lifestyle and basically created from scratch the romantic and enigmatic portrait just described. But probably the most fascinating and persistent myth that emerged from the A-No1 books was the existence of a secret hobo code, presented in unnoticed and almost invisible chalk or charcoal graffiti. This code, composed of cryptic, seemingly ordinary and almost-childish hieroglyphs and symbols, was supposedly used by traveling hobos to transmit messages to their colleagues, such as “Dangerous town,” “Safe place to spend the night,” or “Here lives a nice lady.” It is known and well-documented (mostly through the work of filmmaker Bill Daniel) that the practice of signing the side of wagons and rail post with their personal monikers was and still is a spread practice for hobos and railroad workers in America. But with respect to a secret code that transmitted useful messages from hobo to hobo, there is not much evidence that it actually existed. After all, why would the hobo, a supposedly elusive and off-the-grid character, want to make public their own secret means of communication? It is not unfair to assume that the publication of the hobo code was probably nothing more than a ploy to fabricate and maintain that same legendary elusiveness.

Either way, thanks to Leon Ray Livingston’s works, the hobo’s supposed secret code became a common emblem of the intriguing and puzzling (and pretty much fantastic) mysteries of industrial civilization’s own underground realities. It seemed at the same time spooky and exhilarating to imagine that the unstoppable machine of progress was leaving behind, in its own dark residue, a striving secret society of outcasts and ostracized rebels living an almost chivalrous adventure, having happily exchanged social status and at times mental health to be free of the oppressive commands of power. I think it goes without saying how popular this common narrative has stayed throughout the years in science fiction and, more generally, in popular culture. The mystic figure of the marginalized can be tracked from the charming and magical homeless lady in Frank Capra’s A Pocketful of Miracles, to the cyberpunk Martian mutant separatists in Total Recall, to the Lo-Teks in Johnny Mnemonic and the Nebuchadnezzar crew in The Matrix series, just to name a few. These cyberpunk re-imaginations fall under the myth of the “hidden utopia”: the assumption that the hopes of resistance against the conspiracy of modern civilization lays in a counter-conspiracy of the outcasts, the unlikely sub-inhabitants of its most obscure and remote corners.

Leon Ray Livingston’s “signs used by Tramps” in his 1911 book Hobo-Camp-Fire-Tales, written under the A-No1 pseudonym.

This is exactly what is deployed by Pynchon in The Crying of the Lot 49. Or, at least, this is how a borderline-paranoid protagonist tends to imagine a seemingly active but always evasive conspiracy, as if the myth of the hidden utopia could be also a borderline-paranoid fantasy of those made anxious and disoriented by postmodern subjectivity. It’s also possible to observe the echo of the hobo graffiti’s legend in Pynchon’s book, as the W.A.S.T.E. logo, a simply drawn muted cornet, suspiciously similar to the purported signs of the hobo code, appears to have been placed all over the most seemingly mundane corners of Oedipa’s reality, such as on the walls of a public bathroom or on the edge of a sidewalk.

But the recovery and use by Pynchon of these older cultural cues is not an idealization of the hidden problems of the homeless and the marginalized. After all, any social articulation outside the limits of the community itself can easily turn into a contradiction, a fantasy, a paradox not allowed by the predominant culture. If the whole world has been conquered by malignant forces and crooked interests, the possibility of a constructive, non-nihilistic escape from this system literally lays outside of this world. That’s why Pynchon, as Oedipa, finds himself at a dead end, accepting that, if W.A.S.T.E. and its obscure conspirators were to exist, its own definition would prohibit the final revelation of its actual existence. That’s good for Pynchon, who playfully explores the literary potential of such contradiction, but it ain’t so good for Oedipa, who is still and forever trapped in modern society, and seems destined to always live on the epistemic edge of paranoia, unable to determine if everything she experiences is a convoluted prank by her ex-lover, if she has gone definitively crazy, or if W.A.S.T.E. is, in fact, real.

In a dream-like episode in the middle of the novella, Oedipa encounters an old ex-anarchist friend, Jesús Arrabal, who, torn apart by the demise of the emancipatory narrative, has to admit to her the metaphysical impossibility, or at least almost supernatural essence, of any revolutionary promise: “You know what a miracle is. Not what Bakunin said. But another world’s intrusion into this one.” Alien invasion? Religious intervention? Not quite, but similarly unlikely: the possibility that, under the all-mighty and ubiquitous forces of the Machinery and the cannibalistic and expanding logic of Capital, there could have formed a secret alliance of those who have been cast out of society, those who inhabit the obscure nooks of the dirt and the piles of garbage, under the colossal figure of the ominous constructions and highways. Like parasites in the wires of modern communication systems, these posited liberatory beings have been exiled in a land “invisible yet congruent with the cheered land [Oedipa] lived in,” barely but firmly surviving out of the realm of the living, right next to where we stand, but nevertheless unnoticed by the naked eye.

![]() Pepe Tesoro is a philosophy PhD student from Madrid. You can follow him at @pepetesoro.

Pepe Tesoro is a philosophy PhD student from Madrid. You can follow him at @pepetesoro.

Reviews / November 14, 2019

Italianamerican

ItalianamericanAfter Martin Scorsese burst onto the scene with the one-two social realist punch of 1973’s Mean Streets and 1974’s Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore, he produced an ode to the milieu from which he sprang, a briefer-than-feature-length trip to his parents’ walk-up apartment in Little Italy for Sunday macaroni and gravy: 1974’s Italianamerican. The film is many things: an obvious love letter to Scorsese’s parents and to Italian culture, something of an anthropological expedition investigating his own roots, and ultimately an examination of how the combination of higher education, cultural assimilation, rejection of religion, and flight from urban ethnic enclaves to the suburbs changed the children of these first-generation European immigrants. Scorsese’s 1974 trip back to his folks’ house exposes the Italian-American experience in all its contradictions and quandaries: in gender relations, race relations, conceptions of social class, family life, and nostalgia and memory.

The relationship between (Luciano) Charles Scorsese and his wife Catherine (née Cappa) is obviously the center of the film. While Martin does appear and does prompt questions, Italianamerican is best when we’re watching the four-decades-married couple squabble and bicker and tease each other. One notable piece of Italian-American culture that emerges from the film is the complex web of gender roles and relationships that characterize the Italian family. Charles deals in a few stereotypical sexist behaviors that one might expect of someone of his generation, but it’s clear that Catherine (and by extension Italian-American wives and mothers) isn’t having any of it. One exchange on cooking (a topic that comes up again and again in the film) says it all; Charles explains with a smile that he doesn’t cook because “I’m not supposed to… it’s not my line,” while simultaneously claiming that, even so, men are the best chefs: “It’s been known that a man is a better cook than a woman any time.” Immediately, Catherine snaps back with a simple, “Then why aren’t you doing the cooking then!”

But ultimately both Charles and Catherine recognize the purely enormous amount of unpaid labor that Italian mothers had to do back in their day: cooking and cleaning for nine kids, all while taking on outside jobs that could be done at home, like sewing piecework: “Our poor mothers worked.” Modern conveniences such as washing machines have banished much of this drudgery, but both of the elder Scorseses seem humbled by the sacrifices their own mothers had to make. Charles, especially, is touching as he remembers his late mother being unwilling to suffer fools and quite capable of defending herself in any conflict: “As far as my mother goes, my mother was a strong woman… If she had to say something, she told you and that was it and you couldn’t answer her. My mother, she was a real whip.” After this statement, Charles’s hand goes to his mouth (as does Martin’s, I noticed, an uncanny example of familial mirroring), obviously choked up at the memory. Italian-American femininity, with its focus on being strong, being tough, being protective of one’s children, being able to hold one’s own in an argument, was born on the mean streets and tenements of major cities all over the Eastern seaboard in the early 20th century and most definitely would not have jibed with the contemporary WASP image of how a bourgeois woman, wife, and mother should act.

Mentioning the particular social environment in Lower Manhattan that housed and sheltered waves of Southern and Eastern European (and East Asian) immigrants in the early 20th century, it’s clear that even as ethnic groups formed their own enclaves, they were forced to deal with different groups as a matter of course in America’s “melting pot.” Charles recalls the way Little Italy and the Jewish enclaves on the Lower East Side would find themselves side-by-side in workplaces, public spaces (like the pushcarts and public markets on Delancey Street), and restaurants (Charles is insistent with Martin on making sure he notes that the home of “the original potato knish” is Schimmel’s.) “All together, Jewish and Italians, they all worked together,” Charles says, as he remembers lighting stoves and lamps for observant Jews on the Sabbath.

As Charles remembers the pushcarts, Martin cannily cuts in images of the Lower East Side, Little Italy, and Chinatown as they stood in the then-present of 1974: it’s still a multi-ethnic neighborhood with pushcarts and kids playing in the streets, demonstrating the continuity of four generations of immigrant communities in New York City. And it’s not just fellow white immigrants who the Scorseses identify as being unfairly treated by the power structures of the time. “People were afraid to walk through [Chinatown]; you used to hear so many stories about it, but it wasn’t true!” Catherine fairly screams. (Charles is admittedly a bit more ambivalent about Chinatown, but Catherine holds her own.) Throughout Italianamerican, Catherine demonstrates a very ingrained sense of racial solidarity, likely due to the awareness that Italians had been on the end of that exact kind of discrimination when they were “fresh off the boat.” Even when Charles makes a comment about how the preexisting Irish population of their neighborhood systematically mistreated the more recent immigrant arrivals from Southern and Eastern Europe, Catherine also makes sure to make a point of disagreeing with Charles’s intimation that the number of bars in the neighborhood indicated that the Irish of the time were all drunks.

With that in mind, it’s clear that there is some anxiety among the elder Scorseses’ generation around their immigrant identity and assimilation into the predominant American WASP culture. Early on in the film, Charles spends some time taking Catherine to task for “putting on”: elevating her tone from her customary lower Manhattan accent and mannerisms. After being hectored about this “code-switching,” Catherine responds in a broad New York Italian accent, shouting from off-screen: “I don’t know what you mean, Charlie!” “Talk the way you’re talkin’ to me now, that’s what I mean,” Charles responds with a knowing smile. This anxiety about assimilation and forgetting one’s origins in Italianamerican helps set the stage for so many of the subsequent conversations that the couple conduct about class, ethnicity, and making it in America. Throughout the film, the elder Scorseses discuss numerous gradual processes of cultural assimilation: for example, while Charles’s family didn’t believe in having a (American) Christmas tree when he was young in the 1920s, it’s clear from the Scorsese family photos from the 1950s that Martin grew up with American traditions like hanging stockings at Christmastime (from a radiator, not a fireplace). In a story Catherine tells about her father shaving his handlebar mustache after a week-long work assignment in New Jersey, which scared the kids because he looked so different upon his return to Manhattan, there floats the unspoken possibility that he was asked to shave the Old World facial hair for reasons of the job itself. (Speaking of facial hair, there are a couple of passive-aggressive generational pokes at Martin’s thick beard from both his mother and his father.) The most striking moment surrounding assimilation is the tale Catherine tells about her father’s citizenship interview, where Catherine’s sister had to act as interpreter; as the immigration agent’s reaction to the elder Cappa’s inability to speak fluent English is one of shame and disapproval: “Why that’s terrible!” Family lore insists that Catherine’s father used this opportunity to show off a little of the English he had picked up during his time in America, telling the immigrant agent, “Go and fuck yourself.”

There are also omnipresent reminders of class. The traditional tale of European immigration to America is the idea of fulfilling “the American dream,” usually by making one’s material fortune in the new land of opportunity. Charles notes the advice he received to not work for someone else, and instead work for yourself: “You’ll always have money in your pocket.” The hard times, the sacrifices, the traumatic journey to America itself (Catherine insists her mother was so scared of the prospect of a transatlantic sea journey that she had to be tricked onto the boat): these stories clearly loom large in the Scorseses’ family narrative, as with many European immigrants of the first generation. Details about the grimness of the tenement apartments and poverty abound in the elder Scorseses’ telling, but Catherine also luxuriates in the moments when her generation began to find work and make “real” money; the story of one of her brothers starting off as a messenger boy for quintessentially old-money WASP investment firm JP Morgan so that they can afford Christmas presents and “a proper tree” contrasts with Charles’s tale of his folks not wanting an American Christmas tree. Occasionally, it’s hinted that Charles’s family was a little bit poorer than Catherine’s; Catherine notes in a conversation about making wine that her family made theirs in the basement instead of the kitchen like Charles’s family did. Catherine makes repeated reference to her family’s wanting their house to look less like a tenement, citing the desire to “better yourself,” hinting that Charles’s allegation that she was “putting on” at the outset of the film might have been at least a little correct.

The perfect confluence of these issues around class consciousness and assimilation lie in the Scorseses’ tale of finally taking their long-promised honeymoon. Instead of their scuttled original plan to visit Niagara Falls when they were first married, they go (one imagines thanks to Martin’s success and largesse) on a two-week trip to the Italian peninsula where they visit family in Sicily and see Rome and Venice as American tourists forty years after their wedding. It’s notable that while Catherine obviously enjoyed all the trappings and privileges of the return to Italy, she also feels intense guilt about the poverty in the countryside that was still in evidence in the 1970s: “The land is so beautiful, but there’s no work over there!” She nearly weeps when she thinks about a young boy who wanted to be taken back to America with her, and makes a poignant Freudian slip in saying that she wished she could take him back on “the boat” before correcting to “the plane.” Catherine’s proximity to the immigrant experience of her mother allows for an empathetic realization: that her ancestors’ emigration was an escape from real endemic generational poverty, and that her position of privilege as a comfortable Italian-American on a two-week tour of Italy will not allow her to save the descendants of those who were left behind. It’s heartbreaking to watch, but it demonstrates that those memories of her ancestors left her with something tangible: a lasting, innate awareness of right and wrong.

It’s hard for me to remain completely unbiased about Italianamerican, of course, mostly because the Scorseses’ apartment, in its studied and cluttered Old World decor combined with mid-century Italian-American touches (plastic wrap covering the “nice couch” in the living room) reminds me vividly of my own grandparents’ apartment in East Boston in the 1970s and ’80s (as does Catherine’s insistence on vacuuming and cleaning up as soon as Martin is done shooting the film; my own grandmother’s obsessive cleanliness is recounted in family lore every time my father recalls being whacked with a broom to get him to clean up after himself). As examples of members of the generation that decided not to leave the old neighborhood for the suburbs like their late Silent and Baby Boomer kids did, the elder Scorseses are indicative of a bifurcation that was overwhelmingly common among ethnic whites in the Cold War era. In that move to the suburbs—under the larger rubric of “white flight“—came a concomitant distance from one’s neighbors, a certain financial and material security upon entering the American middle class, and a forgetting of one’s origins, both cultural and class, which led in many cases to an inevitable shift among many non-WASP whites to the political right. But those Italian-Americans of Catherine and Charles’s generation, still situated in the old neighborhood, didn’t completely forget that, once, we “all worked together.”

This awareness of the solidarity of the old neighborhood finds its most powerful expression in the way both the Scorseses tell their stories for Martin’s camera. In the final third of the film, with Sunday dinner being picked at over the dinner table, the Scorseses remember how important telling “fantastic stories” was in an era before the radio and the television, purely for purposes of entertainment. (It’s no surprise that the role Catherine eventually became famous for, as Joe Pesci’s character Tommy’s mother in 1990’s GoodFellas, involves her telling just such a humorous tale from the old country about a cuckolded husband, a story type with ancient origins in Italian literature and culture.) One of Catherine’s stories in Italianamerican, which touches upon the spooky and the supernatural matrix of the Old Country, oddly becomes an inadvertent parable for all the class anxieties expressed throughout the film. In this story, a mysterious visitor clad in silver appears, Communion-like, at the foot of Catherine’s mother’s bed back in Italy while she is nursing a young child—the next generation—and asks her to “hit me with something” to receive great wealth. Catherine’s mother, petrified by the visitation, hesitates, clutching her child (destined to be an American) to her breast. Years later, a trove of silver coins is found in the home after they’d left; family members, remembering the story, blame her for not lashing out at the mysterious alien stranger and becoming rich.

In a way, though, that sort of a devil’s bargain is real, and is expressed in the way the Italians, the Poles, the Greeks, and many other non-WASPs “became white” in the second half of the 20th century. And oral storytelling like this—from generation to generation—helps to convey important cultural messages that might otherwise be forgotten in the stultifying white conformity of the red-lined, middle-class suburbs. The stories our elders choose to tell and hand down are vitally important to not forgetting our origins as well as remembering and preserving moral lessons—lessons of familial loyalty, of brave, hard-working matriarchs, even lessons of class and cross-ethnic solidarity (even if neither of the Scorseses speak in such blatantly political terms) purchased at great cost. If every Italian-American MAGA-swallowing stronzo in 2019 who talks about their ancestors immigrating “the right way” could really listen to what the elder Scorseses were saying in Italianamerican about solidarity—solidarity with laborers, with recent immigrants, with working mothers, with the ethnic “Others” in the neighborhood, a sense of community hard won, prompted by real harassment and oppression of their own ancestors at the hands of cops and immigration officials—they might begin to understand why they’re wrong, and why they’ve always been wrong, to accept the poisoned pill of American kyriarchical “whiteness.” Martin Scorsese knew, even as a hungry 31-year-old filmmaker—and he remembers today, 45 years after Italianamerican was released—that the stories we choose to tell and to preserve matter, that the voices we choose to amplify with our privilege matter, and that even in a family lark like Italianamerican, that belief shines through, like a trove of silver treasure.

![]() Michael Grasso is a Senior Editor at We Are the Mutants. He is a Bostonian, a museum professional, and a podcaster. Follow him on Twitter at @MutantsMichael.

Michael Grasso is a Senior Editor at We Are the Mutants. He is a Bostonian, a museum professional, and a podcaster. Follow him on Twitter at @MutantsMichael.

Illustration from "The Beauty and the Beast", 1970

Illustration from "The Beauty and the Beast", 1970 What I wanted to say ... with self-expression, 1970

What I wanted to say ... with self-expression, 1970 Figures, 1970

Figures, 1970 Frog King - from "The Beauty and the Beast" series

Frog King - from "The Beauty and the Beast" series

Untitled, 1971

Untitled, 1971 Second illustration from "The Beauty and the Beast", 1970

Second illustration from "The Beauty and the Beast", 1970

From Series "The Beauty and the Beast", 1995

From Series "The Beauty and the Beast", 1995 Erotic Representations

Erotic Representations The Big Fight, 1979

The Big Fight, 1979

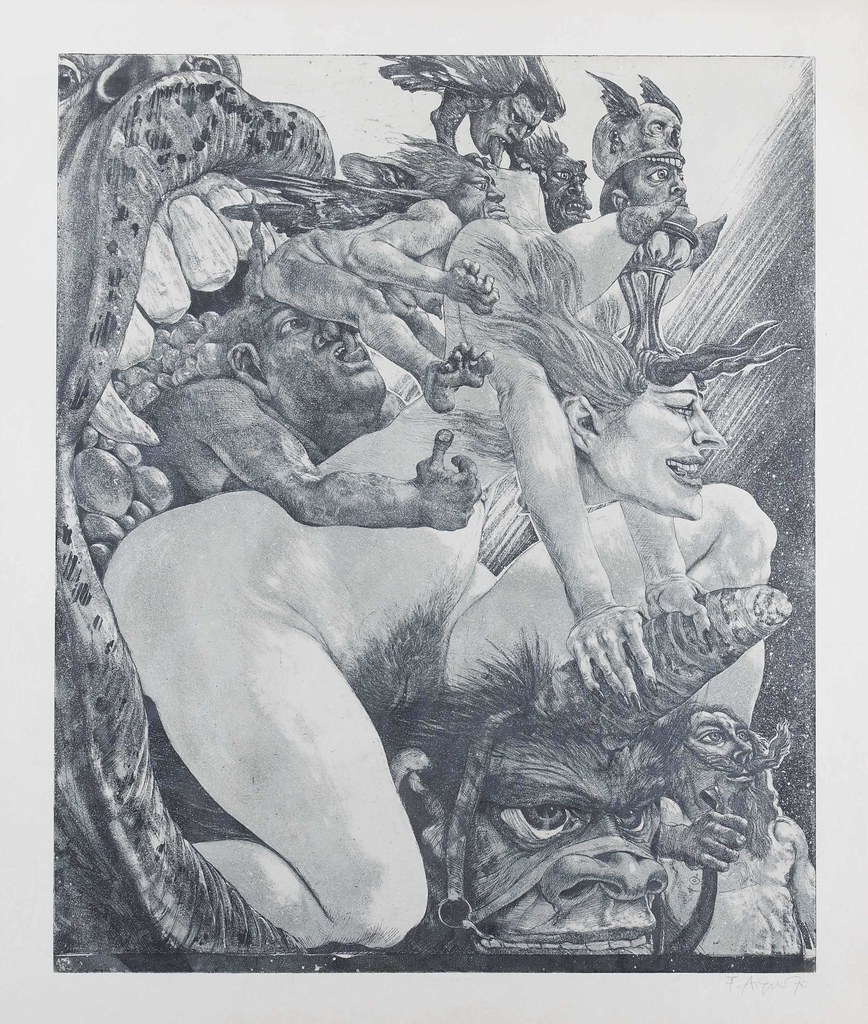

'Taumel' or 'Frenzy'

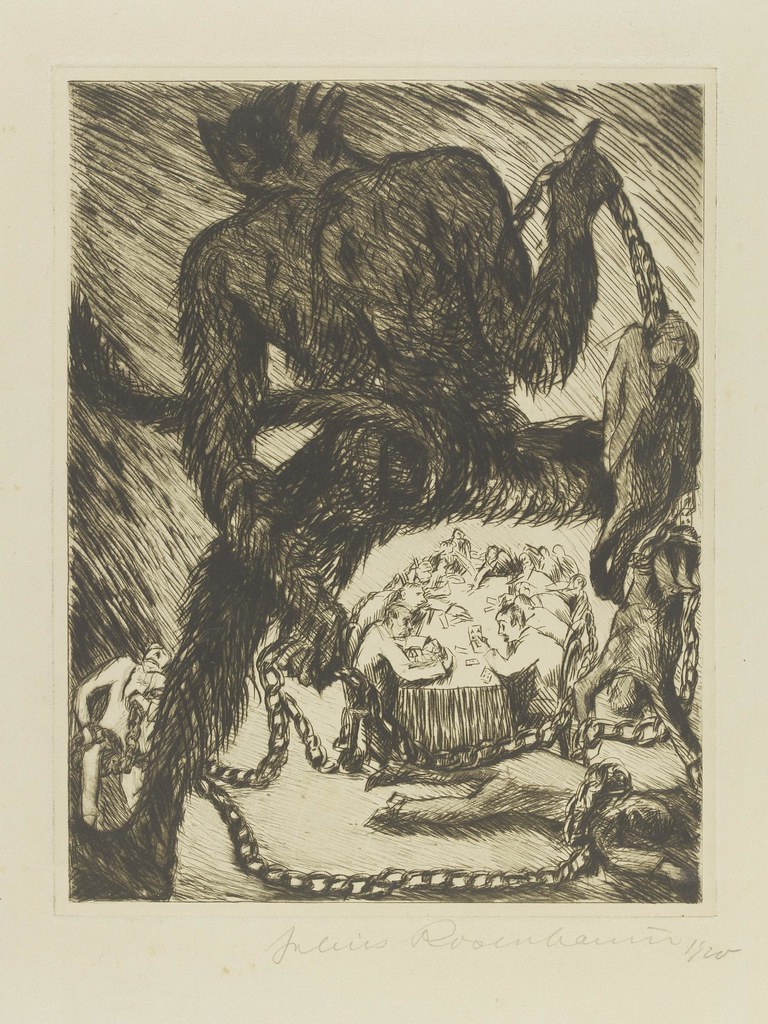

'Taumel' or 'Frenzy' 'Gluckspiel' or 'Game of Chance'

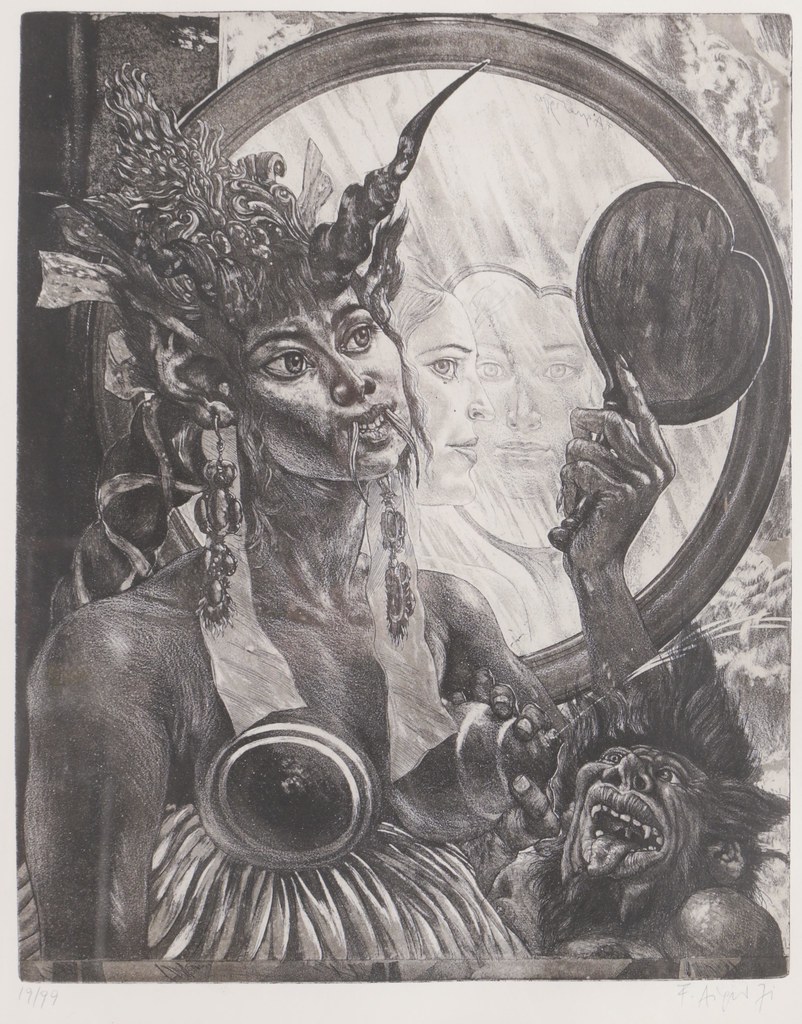

'Gluckspiel' or 'Game of Chance' 'The Devil as Matchmaker'

'The Devil as Matchmaker'