Art & Illustration

Falling Into The Sky: Disappearance, Aviation, and ‘The Twilight Zone’

Grafton Tanner / June 25, 2020

“Really nothing there, is there?”

“Really nothing there, is there?”

—from Duck Pimples (1945)

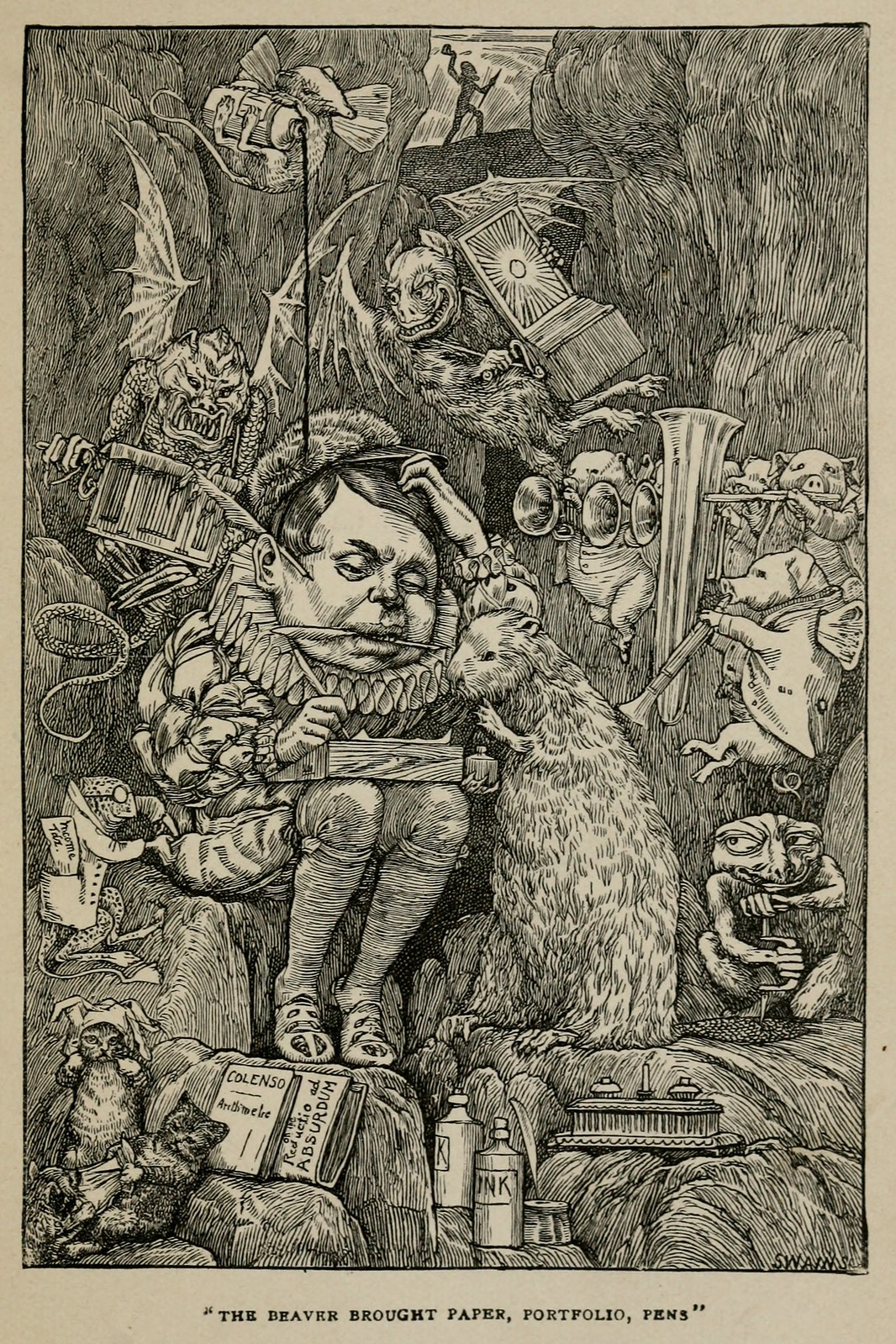

Classic episodes of The Twilight Zone (1959-1964) follow a simple formula. An ordinary person experiences something extraordinary, and we follow along as they figure out what is happening. Very often, the story ends with a twist: the cross-country traveler has been dead all along, the aliens are actually astronauts from Earth, To Serve Man is a cookbook. But not every episode adheres to this formula. In fact, the very best of Rod Serling’s visionary series aren’t so simple.

“And When the Sky Was Opened,” from the first season, is one of the very best. Based on the Richard Matheson short story “Disappearing Act,” the episode tells the story of three pilots—U.S. Air Force Colonel Ed Harrington (Charles Aidman), Colonel Clegg Forbes (Rod Taylor), and Major William Gart (Jim Hutton)—who return from the first voyage into space only to be erased from existence, one by one. The story begins after the pilots have crash landed, but Rod Serling’s opening monologue includes a bit of crucial exposition: the pilots vanished from radar and lost all contact with mission control for twenty-four of the thirty-one hours they were in flight.

After the mysterious and sudden disappearance of Harrington upon landing, Forbes desperately tries to convince Gart that something has taken Harrington from this world, that perhaps “somebody or something made a mistake” and let the three pilots return when they shouldn’t have. Gart, confined to a hospital bed, has no memory of Harrington, and Forbes comes to realize that no one else remembers the pilot. The story ends with Forbes arriving at the horrific realization that he is next to disappear. Begging for his life, he runs screaming from Gart’s hospital room and vanishes. When the nurse fails to remember Forbes, Gart then understands the colonel was telling the truth, and Gart, the aircraft, and the mission disappear without a trace.

The episode is a success for many reasons. The acting is palpable; you can feel the existential horror of the pilots as they come to terms with their absurd fate. As the panicked Clegg Forbes, Rod Taylor gives a dynamic performance of a man splintering into madness, and when the supporting cast gawks at him with pity, you start to wonder whether Forbes is really delusional. The episode also refrains from ending with a twist. There is no grand surprise at the end, only eerie ambiguity. Something has disappeared the pilots from existence. Without a conclusive reveal, all we’re left with is a lingering cosmic horror—the bizarre, nauseating suspicion that the universe operates according to unknown logic. Perhaps there’s no logic at all.

Like every Twilight Zone episode, “And When the Sky Was Opened” reflects both modern and timeless human anxieties. It can tell us quite a bit about memory and information loss, about the politics of disappearance both in postwar culture and in today’s time of social amnesia, when too much information inevitably causes some things to be remembered and others to be forgotten. And the episode uses aviation to reveal the politics of social forgetting, exposing the truth that only those who remember the past disappear.

“And When the Sky Was Opened” is not the only Twilight Zone entry to feature disappearing aircraft. The third season also-ran “The Arrival” tells the story of a commercial flight that lands mysteriously without anyone on board. A detective with a perfect record is assigned the case, and he slowly comes to believe the plane isn’t real. When he attempts to prove this by placing his hand in the path of a spinning propeller, the plane vanishes. The twist? The detective does not actually have a perfect record. In his entire career, there was only one case he couldn’t solve: a missing airplane that disappeared mid-flight years earlier. The empty plane is merely a ghost that has come back to torment him. And in the brilliant “The Odyssey of Flight 33,” a routine flight encounters a strange tailwind that accelerates it past the speed of sound. When the plane slows, the pilots attempt a landing—only to realize they have traveled backwards in time to some prehistoric era. They successfully pick up the tailwind again, hoping to travel back to the present. This time they stop in 1939. The episode concludes with the pilots preparing to ride the tailwind back to the present one last time before the plane runs out of fuel.

“Now, most airplanes take off and land as per scheduled,” Rod Serling reminds us in his opening to “The Arrival.” “On rare occasions, they crash. But all airplanes can be counted on doing one or the other.” Except when they don’t. Serling wrote Twilight Zone plots around vanishing airplanes because he knew they shake our faith in a thinkable world. How can something so huge and with so many people involved simply vanish?

***It’s a question asked in the wake of every major aviation mystery, from Flight 19 to the recent disappearance of Malaysia Airlines Flight 370. The commercial flight took off from Kuala Lumpur International Airport and headed to Beijing on March 8, 2014. It never landed. Shortly after takeoff ATC lost contact, and the plane, with its 239 people on board, disappeared from radar. The search for it became the most expensive in aviation history, but nothing was found. Some say it crash landed; others have speculated it was hijacked. There is no consensus among investigators.

James Bridle calls aviation a “site where technology, scientific research, defense and security interests, and computation converge in a nexus of transparency/opacity and visibility/invisibility.” But it’s more than that. For over a century, aviation has been the engine of information science, as well as the proof that once-impossible dreams can come true with the help of mighty computing power. Along with the realization of human flight came unprecedented connectivity, which in turn caused an explosive outbreak of information: projections, predictions, models, and data. Over the twentieth century, technology progressed at a dizzying rate. Planes, along with everything else, got faster. “At such an exponential rate,” David Graeber writes, “it must have seemed reasonable to assume that within a matter of decades, humanity would be exploring other solar systems.”

And then something strange happened. Technological advancement slowed in some areas, and planes were no longer quite as fast. While aviation slowed, however, information science did not. Today, futurity is measured not by the speed of an airplane but by the speed of WiFi. A technology today seems futuristic if it provides us with a steady drip of information, of which there is more than could ever be analyzed by anyone. The so-called infodemic—a viral outbreak of information and misinformation—did not start with the 2020 outbreak of COVID-19. It’s been ongoing since the birth of the information age, and it’s only gotten worse.

Without aerospace science, funded largely by the military, there would be no information age, for aviation is only possible via advanced information technologies. The disappearance of planes, such as Malaysia Airlines Flight 370, proves that information can vanish too—a shocking truth almost too horrible to bear in our control society. “For everything that is shown,” Bridle writes about plane-tracking, “something is hidden.”

Information loss is a natural occurrence, and it’s especially prevalent—and dreadful—in a society obsessed with eliminating unknowns. But sometimes, disappearance is artificially induced to serve certain interests. Ideas that challenge ruling ideologies, the ones that resist capital especially, are erased. Memories of radical events are written out of history, consigning non-normative knowledge to the margins—very often deleting them from the official account altogether. If they do survive, traces of these events hunker underground, or they hide beneath the cover of normativity, passing as “appropriate” but occasionally winking from behind the veil at those who also know. If they are eradicated, stamped out of the cultural script, radical memories will always return as ghosts, terribly inconvenient reminders of an alternative future that was foreclosed by capitalism. This act of hauntology, of the forgotten past haunting the present with visions of lost futures, is crucial for collectives to combat the neoliberal “eternal” present—if only we could remember.

Information loss is a natural occurrence, and it’s especially prevalent—and dreadful—in a society obsessed with eliminating unknowns. But sometimes, disappearance is artificially induced to serve certain interests. Ideas that challenge ruling ideologies, the ones that resist capital especially, are erased. Memories of radical events are written out of history, consigning non-normative knowledge to the margins—very often deleting them from the official account altogether. If they do survive, traces of these events hunker underground, or they hide beneath the cover of normativity, passing as “appropriate” but occasionally winking from behind the veil at those who also know. If they are eradicated, stamped out of the cultural script, radical memories will always return as ghosts, terribly inconvenient reminders of an alternative future that was foreclosed by capitalism. This act of hauntology, of the forgotten past haunting the present with visions of lost futures, is crucial for collectives to combat the neoliberal “eternal” present—if only we could remember.

When American soldiers returned from World War II, they came back bearing secret knowledge: the horrors of warfare and the absurdity of power. Waking up as civilians, the returned had their memories wiped by the burgeoning postwar consumer society, which promised pleasure through purchasing and fixed gender roles as binary, locking into place a suffocating bureaucratic rationality that extended from the corporate sector to the body. Like the pilots in “And When the Sky Was Opened,” those who remembered had to disappear for the postwar dream to persist. Rod Serling served in WWII and witnessed the carnage of war firsthand in the Philippines. He grew familiar with the randomness of death during his service. He saw a fellow private decapitated by a falling food crate while telling a joke. The collision of comedy and death stunned Serling, who was eventually awarded the Purple Heart but experienced difficulty returning to civilian life—how far removed it was from war’s chaos. To cope, he filtered his knowledge through the medium of television, encountering fierce resistance from studio executives as he created The Twilight Zone, itself an indictment of unbridled power disguised as a fantasy series.

By the time Serling died in 1975 from a series of heart attacks, Augusto Pinochet was forcefully disappearing thousands of political opponents in Chile. Animated by American free-market ideology, Chile began a neoliberal conversion in the 1970s, and anyone who opposed it was punished. Some were thrown from helicopters into the ocean; others simply vanished. Decades later, the United States would wage its own regime of disappearance. Conducting “extraordinary rendition” in the wake of 9/11, CIA agents abducted so-called enemy combatants, transported them to makeshift prisons, and tortured them for information about global terror cells. Forty of these combatants remain at Guantanamo Bay, a concentration camp operated by the United States. The prisoners kept there are “ghost detainees”: neither dead nor alive, liminal, in between the cogs of a ruthless penal machine beholden to no one. Their flickering presence/absence haunts the American imaginary.

Living with the knowledge that things will disappear is a dreadful existence, made all the more horrible when we understand that not all disappearances are accidental. Realizing something erased his co-pilot and lifelong friend from existence, Colonel Forbes is sick with dread. He knows that erasure is an act of historical violence. It is a singularly cruel feat to exterminate every last memory of a person, especially if they carry a truth that reveals the hideous countenance of injustice. Capitalism is a disappearing act. Work is contingent; markets, volatile. Things are stable until they aren’t—which means they never truly are. When the sky opens, only the privileged survive. Only the amnesiacs are left alive.

![]() Grafton Tanner is the author of The Circle of the Snake: Nostalgia and Utopia in the Age of Big Tech and Babbling Corpse: Vaporwave and the Commodification of Ghosts. His writing has appeared in The Nation and the Los Angeles Review of Books.

Grafton Tanner is the author of The Circle of the Snake: Nostalgia and Utopia in the Age of Big Tech and Babbling Corpse: Vaporwave and the Commodification of Ghosts. His writing has appeared in The Nation and the Los Angeles Review of Books.

Cottage Cosmos: Alan Jefferson’s ‘Galactic Nightmare’

Richard McKenna / June 23, 2020

Bear with me, because this might get a bit rambling: the way I see it, in a healthy world, not only would we have in hand the levers of the factories, we’d also have the tools for our own artistic fulfillment. And to anyone saying that the tools are there for the buying if you just toil away at the grindstone long enough, I’d reply that tools aren’t simply physical artifacts. Tools are also time, the mental structures like self-belief, the very idea of art as something worthwhile—all of which are etched upon your cerebral cortex by your environment and your upbringing. It isn’t just because we can’t afford brushes that most of us don’t become artists—though for plenty that actually is the reason—it’s because if we do have spare time, we’ve often been trained to feel that art and creativity are not worthwhile ways of using it.

None of this is helped by the establishment’s ongoing drive to turn the clock back to 1902 and formalize creativity into a narrow set of structures accessible only to the wealthy or those the wealthy choose to sponsor. We’re trained to consume their creativity instead of employing our own, so that our “betters” get the structures, spotlight, and funding to follow their muses while our own muses are left moldering in our heads. I don’t mean by this that each of us is necessarily a budding Mozart; I mean that art shouldn’t only be in the hands of those the establishment decides are budding Mozarts—and that Mozarts are in any case an unhealthy metric for judging the value of creativity.

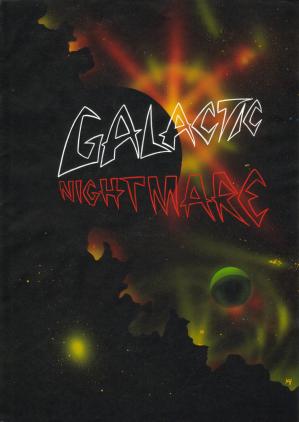

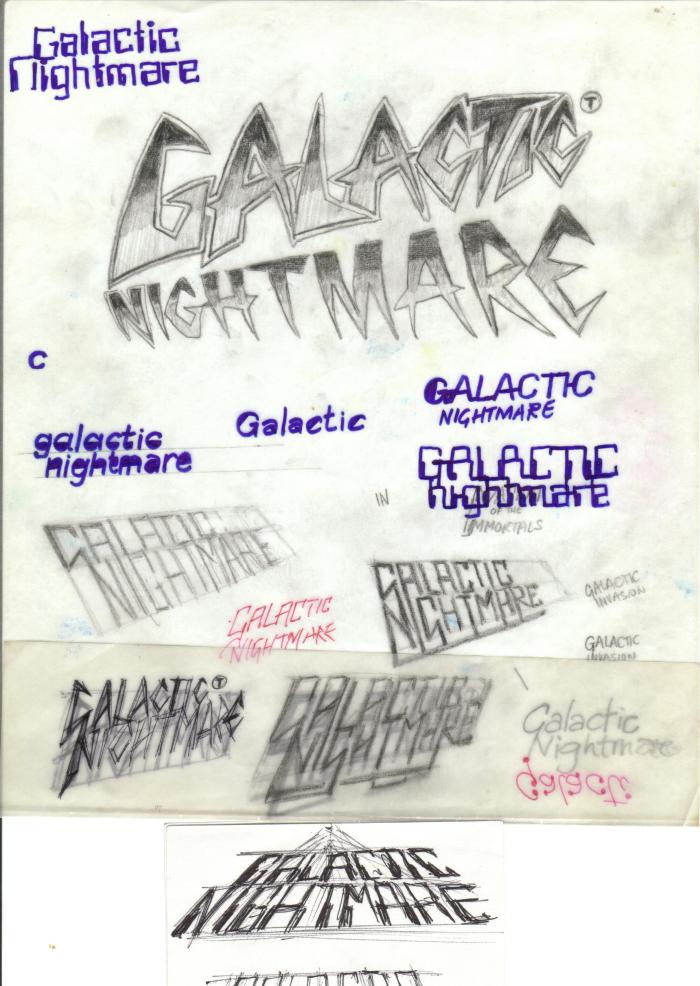

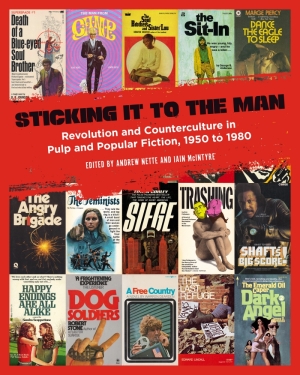

The front page of the Galactic Nightmare story file

Yet, despite all that, fully-formed miniature Mozarts do sometimes appear and seize the tools of creativity for themselves—occasionally at the helms of gleaming spacecraft decked out with banks of pulsing synthesizers. Such is the case of Alan Jefferson, the self-taught polymath behind Galactic Nightmare.

I appreciate that this is a roundabout and slightly bombastic way to start an article about an alien war rock opera concept album made partly in a bedroom in Hull, but Galactic Nightmare deserves flights of rhetoric. Composed, written, played, sung, recorded, and illustrated almost in its entirety by one young Yorkshireman, it tells the tale of how computer expert Doctor Larson discovers a series of extraterrestrial transmissions describing an attack on the inhabitants of planet Zeon by a race known as the Immortals, who plan on using them as cell donors for the serum that gives them their longevity. The Zeons eventually win out, but Galactic Nightmare ends with a newsflash warning that the Immortals are beginning their invasion of Earth.

I don’t know how many of you have been walking around for years with vastly detailed imaginary worlds inside your heads—I know I have—but listening to Galactic Nightmare feels like watching somebody’s head split open, their imaginary world bursting out in full laser-lit, synth-blasting glory: an effect only made more intense by the lovely artwork Alan himself created to illustrate it.

“[I] worked as a milk man on my father’s milk round at Featherstone for a short time before leaving to attend Wakefield Art College when I was 17, where I completed a three year graphic design course,” says Alan. “I left to find there were no jobs for graphic designers without experience and ended up as a corrugated box designer.” After a year of low-paid work in said box design, and a period of low-paid greeting card illustration, he decided to pack it in and go freelance.

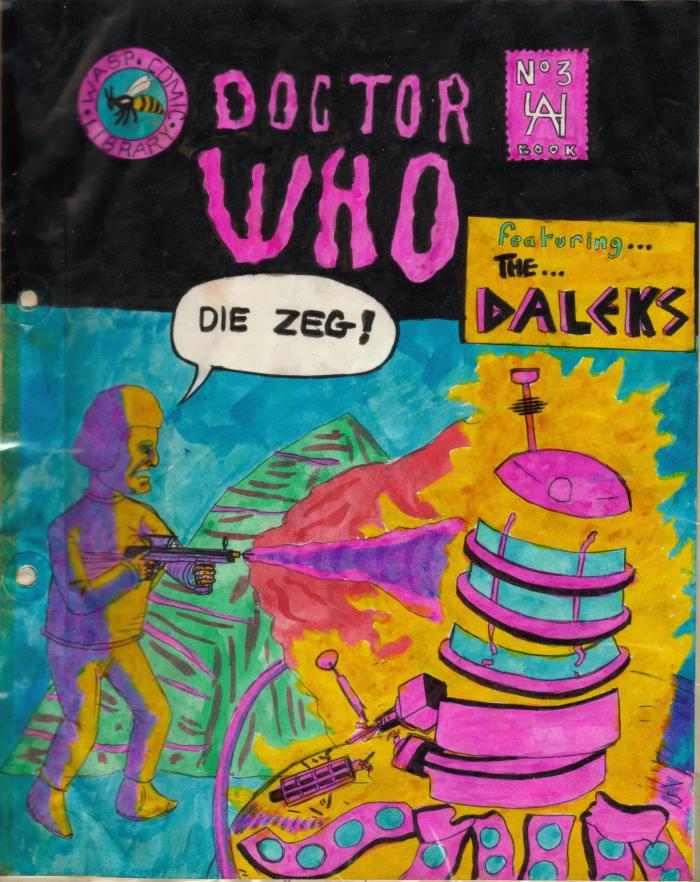

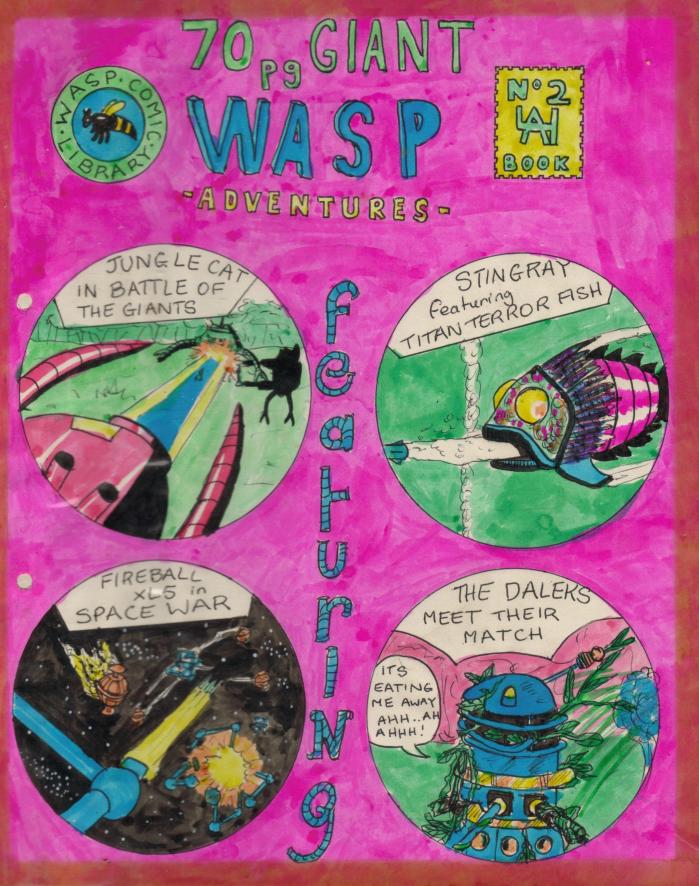

Together with a love of art, Alan had long nurtured an interest in recording and making music, becoming involved in it, like many kids, by taping songs from the radio and TV: “I had a reel-to-reel tape recorder when I was 13 and used to tape singles from Top of the Pops with the microphone attached to the TV speaker grill. So I had always been interested in listening and recording music from a young age, but as for playing, that came much later… I was more interested in drawing, making my own SF comic books, and playing football and cricket in the school teams.”

A few examples of Alan’s homemade comics

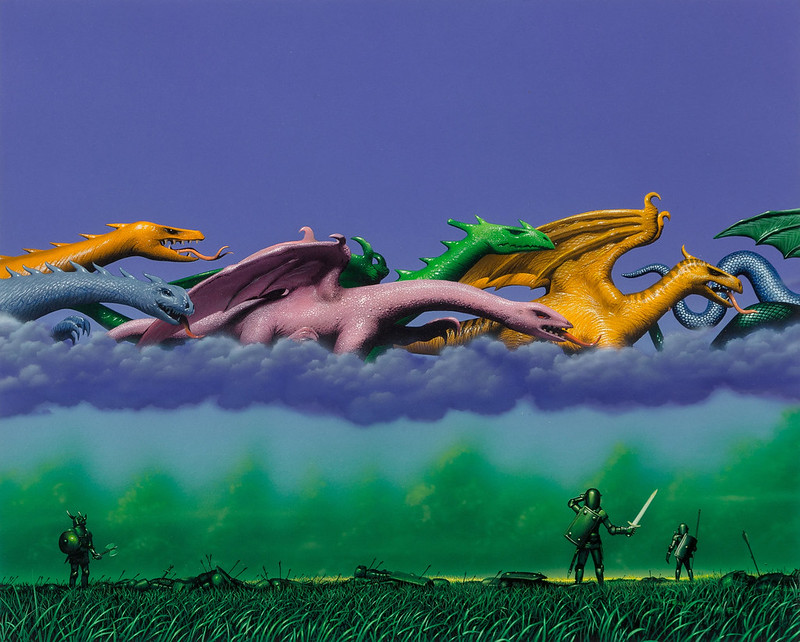

Alan had been a science-fiction fan since he was a child, drawing his own comics inspired by the strips in the Gerry Anderson TV21 comic and The Eagle, his brightly-colored imagery revealing a vivid personal aesthetic that would later erupt in the artwork for Galactic Nightmare. “The First SF film that inspired me as a child was Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea,” Alan recounts, “[then at] art college, The Omega Man, Planet of the Apes and 2001: A Space Odyssey… and This Island Earth.” With its glowing, unearthly palette and wars on distant planets, it’s perhaps the mood of this last film that Galactic Nightmare most evokes.

Alan’s interest in music led to him working his way up from a tiny squeaking Stylophone to an electronic organ, upon which—inspired by things like Keith Emerson’s crazed antics in The Nice’s performance of “America” on BBC2s Old Grey Whistle Test and Uriah Heep’s performance of “July Morning” on the same program—he undertook to learn to play. “Having no formal music training—as my school had six hours of music in four years and only had kazoos to play—this was extremely ambitious, but I managed it. I then purchased a dual portable organ keyboard and Korg synthesizer and continued to learn songs by ear from records.”

One of Alan’s youthful paintings, inspired by 1955’s This Island Earth

Alan’s art college friend Jack Stoker played guitar and had a deaf next-door neighbor that meant they could rehearse without complaints, so once a week Alan would “… pack my gear into the Mini and make my way to Garforth were we would play the songs I taught him to play. At this time I got the Mini Moog synth due to being impressed by Ken Hensley using one on stage and on records in Uriah Heep.” (And I think we can all appreciate the recursive beauty of a Mini Moog being transported around West Yorkshire inside a Mini.)

After Alan and friend had been playing together for about five years, he purchased a four track TEAC reel-to-reel recorder and mixer to do multi-track recordings, initially recording instrumental covers, laying down each sound separately on the four track and gradually overdubbing, before starting to write original songs that eventually evolved into the demo for an SF concept album influenced by Uriah Heep, Deep Purple, and Boston. Alan sent it around the record companies, but the lukewarm response was that it was not commercial enough.

In 1979, after hearing Jeff Wayne’s 1978 double-LP rock opera adaptation of H.G. Wells’ War of the Worlds, Alan decided to give the SF concept album another try, this time basing it around a narrative. “I had a title for a song called ‘Giant Metal Monsters’ which I wanted to incorporate into the story. So I developed the story around that. In order to be different from H.G. Wells’s ‘War of the Worlds’, I placed my story of alien invasion on another planet with alien beings. I would write the song lyrics first or fit the lyrics to the music. ‘Old and Grey’ is a prime example, where I had this chorus riff and thought of the lyrics to fit it. The whole song then developed from that riff, as did the reason for the Immortal invasion of Zeon in the story.”

Some of Alan’s concept artwork for the Galactic Nightmare packaging

Galactic Nightmare was recorded “in fits and bursts over several years, also while recording other non-SF music” in a 12′ x 12′ room in Alan’s house near Pontefract, and completed in a bedroom in Hull using a Tascam 8 Track reel to reel recorder, Teac 4 Track reel to reel recorder, two cassette recorders, a 6×4 and a 6×2 small mixers, Great British Spring Reverb, Electric Mistress flanger, phaser/distortion/ noise gate pedals, Hammond C3 organ with a Yamaha amp/rotating speaker, a Grant Stratocaster copy, AKG/Sennheiser mics, and Paiste hi-hat and crash symbols.

“The complexity of recording all the sounds individually—in real time, no sequencers then—was extremely time consuming,” says Alan. “Frustratingly, there were also the problems of equipment reliability in those days. For example, the Mini Moog was an expensive synth that needed new keys after six months as they were always wearing out! If I had stuck knives in them as Keith Emerson did in his Hammond organ you could understand it.” In fact, the creation of Galactic Nightmare was at times an actually physically dangerous process. “While I was rewinding the Tascam 8-track recorder, another very expensive machine, one of the large eight and a half inch tape reels flew across the room—very dangerous! It was only held on by two small aluminum nuts.”

The process was grueling in other ways, too. “Mixing down was a nightmare, as you needed four hands on the faders to mix all the sounds from the eight track, four track echo, spring reverb, and cassette deck. We had moved back to Hull again so there was only myself to do it. I ended up mixing down a lot of the tracks in sections down on to the four track and then splicing them together with splicing tape. Many splices had to be redone so you didn’t notice the joins,” says Alan. “Now on computers you can have all these things automated apart from joining tracks. But that is also easier to do on the computer.”

In 1985, six years after he’d begun it, Galactic Nightmare was finished. But the record companies’ cool reception to the demo cassette he sent them—together with a 17-page story file, including lyrics and illustrations—convinced Alan to take matters into his own hands. “Rather than waste my efforts, I made improvements to Galactic Nightmare, including re-recording a different beginning and ending, and decided to release version two myself on vinyl LPs. I designed and illustrated an LP cover using updated illustrations from the story file showing elements of the story, hopefully to get people interested in the musical.”

Releasing it on LP proved prohibitively expensive, so Alan opted for a cassette version that would be accompanied by an A2 poster of the cover art and four-page story file. He placed ads in several magazines, but unfortunately his DIY advertising offensive proved unsuccessful, perhaps victim to the mood of the day—consumer tastes were shifting from small-scale experiment to large-scale bombast, and the country’s various cottage industries were rapidly being marginalized. Alan made a second attempt to spark some interest from UK record companies: “[I] got some nice replies, including one from Sir Tim Rice who found it interesting. Stephen Garrett of Channel 4 urged me to turn it into a stage play. Lucas films and Spielberg films returned everything unread/unheard!”

It took thirty years for Galactic Nightmare to get a proper release. Though its initial appearance hadn’t been the success Alan had hoped, pervasive memories of those strange adverts and the few copies that had circulated gradually accumulated a strange momentum of their own over the decades, and in 2015 Trunk Records released a limited edition Galactic Nightmare double LP. The different format meant editing the the original cassette’s 98 minutes down to 88 minutes to fit four sides, and though not one to shy away from daunting undertakings—as the entire story so far should indicate—Alan admits that “[it] was a nightmare to do, even using computer sequencer software.”

This, then, is the story of Galactic Nightmare—a hand-crafted cosmic odyssey whose vast scope ranges between esoteric locales as disparate as Zeon and Mythmolroyd. It remains a stunning DIY chef d’oeuvre, and Alan’s dedication to realizing his own personal vision over the space of years to little interest from an incurious outside world continues to be inspiring. The quality of the whole thing, from the artwork to the production to the music, completely belies its artisan genesis: in fact, perhaps the only thing that gives Galactic Nightmare‘s origins away might be Alan’s vocals—but, strangely, while I’m sure he’d be the first to admit that he might not have the pipes of a Phil Lynott or a Justin Haywood, the earnest, plaintive quality of his voice only makes the album that much more touching and human, and even more clearly the product of one person’s quest to bring to life his own riotous vision as opposed to some slick, corporate box of delights. It’s galling to think that something so unique was snubbed by record companies who were happy to throw money at forgettable “concept album” dross like the Intergalactic Touring Band.

Them’s the breaks, I suppose. Alan is now retired and considering getting involved with music and painting again—to follow along, visit the Galactic Nightmare website he has put together himself—and has also produced an enhanced version three of Galactic Nightmare that boasts two extra tracks and lasts 110 minutes. Let’s all hope that when it eventually sees the light of day, it gets the treatment and reception it deserves. I don’t know if Alan would agree with my ideas about art and creativity, but what I do know is that we should all take his example and try and make more home-produced concept rock operas about alien invasions—or whatever else—because, like Galactic Nightmare, they can only make the universe a better place.

Many thanks to Alan for very kindly agreeing to speak to us and allowing the use of his artwork, all of which is © Alan Jefferson.![]() Richard McKenna grew up in the visionary utopia of 1970s South Yorkshire and now ekes out a living among the crumbling ruins of Rome, from whence he dreams of being rescued by the Terran Trade Authority.

Richard McKenna grew up in the visionary utopia of 1970s South Yorkshire and now ekes out a living among the crumbling ruins of Rome, from whence he dreams of being rescued by the Terran Trade Authority.

“No Bars Between Us”: Joanna Russ, Gwyneth Jones, and the Feminist Utopia

Noah Berlatsky / June 18, 2020

Joanna Russ

Joanna RussBy Gwyneth Jones

University of Illinois Press (2019)

Gwyneth Jones’s new critical biography of Joanna Russ for the Modern Masters of Science Fiction series (called simply Joanna Russ) seems less like an academic reconsideration than a continuation of its subject’s oeuvre. That is part of Joanna Russ’s peculiar genius. Her most famous novel, The Female Man (1975), is (as Jones deftly explains) itself a critical biography of her self, in which four versions of Russ meet and interrogate each other’s motivations, desires, and fates across somewhat more than four different worlds. “The novel’s séance-like structure of competing voices is fiction laid bare,” Jones explains, as her own book becomes another “twisted braid of the author’s mind.” The volume is a polyvocal analysis of a polyvocal analysis, speaking to and about a Joanna who is speaking to and about Joanna. Jones and Joanna (as Jones calls her throughout) are not subject and object, but sister speakers together, most alike when their voices are most individual.

Russ is best known for her science fiction, a genre in which she experimented, and with which she argued, throughout her life. That argument, as Jones makes clear, was primarily a feminist one. In her 1972 critical essay “What Can a Heroine Do?: or Why Women Can’t Write,” Russ declared in all caps “WOMEN CANNOT WRITE—USING THE OLD MYTHS. BUT USING NEW ONES?”

Science fiction and fantasy, with their postulation of distant or future worlds, allowed a rejiggering or reimagining of realism’s tropes, and therefore of realism’s patriarchy. In The Female Man, one instance of Joanna named Jeannine, a younger, sadder, still heterosexual self, wanders through a drab, timid world waiting to marry some drab, timid man. Meanwhile, another instance, Janet, fights duels to the death with rapiers (“apparently, since that’s the kind of scar Janet Evason has to show—though we never see the rapiers,” Jones offers, in a very Russ-like aside) on the all-female alternate timeline of Whileaway. These alternate Joannas are joined by Joanna herself, both as in-novel character and as an authorial voice that comments on her own fictional creations as they appear and disappear from each other’s worlds. The novel is then a realist story (both in the sense that we visit Jeannine’s drab grey realist world and in the sense that Joanna is speaking as her real self). But it’s also an exploration of a science fiction alternative to realism, as the self-confident, unquenchable Janet deftly thumps would-be assaulters in our world, and has duels and adventures in her own lesbian all-female utopia.

The science fiction world of Whileaway gives women room and breadth for feminism. But Jones, and/or Russ, are careful to document the ways in which science fiction itself was mired in the all-too-real conventions of misogyny. Russ’s work was attacked as an exercise in angry man-hating by male SF writers like Poul Anderson and Philip K.Dick, and Russ was frequently frustrated that Ursula K. LeGuin, the most prominent woman writer in the genre, wrote almost exclusively male protagonists.

Russ’s 1978 novel The Two of Them is, in Jones’s brilliant reading, a violent rejection of the science fiction establishment. The novel is the story of Irene Waskiewicz, a transtemporal agent working with her partner Ernst Neumann on a trade deal with the world of Ka’abeh. Women on Ka’abeh are brutally segregated and subjugated. Irene is outraged and arranges the rescue of a young girl, Zubeydeh, who wants to be a poet in contravention of her society’s norms. Irene assumes that Ernst, her lover, will be horrified by Ka’abeh, and that he, like the science fiction genre, will want to free women’s writing. But Ernst drags his feet and warns Irene that their superiors will not support her. Eventually, Irene has to kill him.

The Two of Them becomes not about how Irene and Ernst adventure together, but about how Irene and Zubeydeh have to stand against male institutions on both of their worlds. “As a young woman, longing for escape,” Jones explains,

Russ had found refuge in sf without noticing, perhaps without caring, that women as agents were usually excluded from the game. She’d been faithful for years: explaining science fiction to itself; excusing its faults and trying to transform it even as an ‘out’ lesbian feminist. Maybe she still wanted the relationship to work, as the seventies drew to a close. But her belief in the mission was shaken, and her unease was growing. Was the increasingly difficult position, as an exceptional woman in a male-ordered organization, even morally tenable?

Jones is a science fiction writer herself, and the disillusionment here doesn’t just belong to Russ. Indeed, part of the brilliance of Jones’s discussion of the novel is the way it shifts the meaning of the title again, so that “the two of them” means not Irene and Ernst, and not Irene and Zubeydeh, but Joanna and the community of women in science-fiction, or, specifically, Joanna and Jones. Jones’s reading rescues Joanna from science fiction, just as Joanna’s novel rescues the writers, like Jones, who follow in her interdimensional path.

Jones follows in that path not just as a science-fiction writer, but as a critic. Joanna Russ provides not just careful consideration of the novels, but of Russ’s own reviews and essays. Her critical voice, like Jones’s, is thoughtful, sharp, and delightfully funny. Non-scholars will need to read the book to find out which one of them refers to Stephen R. Donaldson’s Lord Foul’s Bane as “sub-Tolkien” fantasy, and which says that it is a “daydream of Byronic suffering and self-importance… that could easily have been cut by three-quarters.”

By giving criticism and fiction equal weight, Jones (or is that Joanna?) shows with rare clarity how each is embedded in each. Russ’s great 1977 novel We Who Are About To is in large part a critical dissection of the shipwrecked colonization novel. A small passenger vessel crash-lands on a distant planet, and most of the men on board decide they need to start a breeding program to populate the world. The narrator, though, recognizes that they will never be rescued and can’t live on a planet with no usable food or water; she refuses to be raped for a hopeless colonial dream. And so she kills them all.

The book could almost be one of Russ’s devastating reviews—while, for her part, Jones’s analysis of the book is in part an exercise in cross-genre fiction writing. “I found it fun to think of [the characters in We Who Are About Too] as stagecoach passengers—dumped out of their hospitable nineteenth-century world and stranded in hostile Indian country. Beset by peril, these mismatched strangers need a common cause. They don’t realize that the puny outlaw hidden in their midst [i.e., the narrator], who swiftly becomes their scapegoat, is also their nemesis.” Fiction functions as criticism, and criticism involves fictional rewriting. Puncturing imperialist dreams, for Jones and Joanna, is an act of both analysis and imagination. To get to a different and better world you need to be able to cut the old one up and build it anew.

These acts of destruction and creation, of reimagining and remaking, are collaborative. Russ’s vital personal and professional friendships with Samuel Delany and Alice Sheldon dip in and out of Jones’s narrative, as does Russ’s engagement with science fiction, with feminism, and with her teacher Vladimir Nabokov. For that matter, the book reads in many ways as an extended conversation between the protagonists, Jones and Joanna, as they argue, agree, inspire, or think with each other, or near each other, or within each other. It’s a collaboration.

It’s also an elaboration of Russ’s feminist utopian visions of a society that has changed so completely that women can actually talk to each other—or of a feminist utopian vision in which women talking to each other is powerful enough to change the world. Jones (or is that Joanna?) was no doubt inspired by Joanna (or perhaps Jones?) when she wrote in another fiction, which was also another critique: “I dream of another planet, with an ocean of heavy air, where I can swim and she can fly, where we can be the marvelous creatures that we became; and be free together, with no bars between us. I wonder if it exists, somewhere, out there…”

![]() Noah Berlatsky is the author of Wonder Woman: Bondage and Feminism in the Marston/Peter Comics.

Noah Berlatsky is the author of Wonder Woman: Bondage and Feminism in the Marston/Peter Comics.

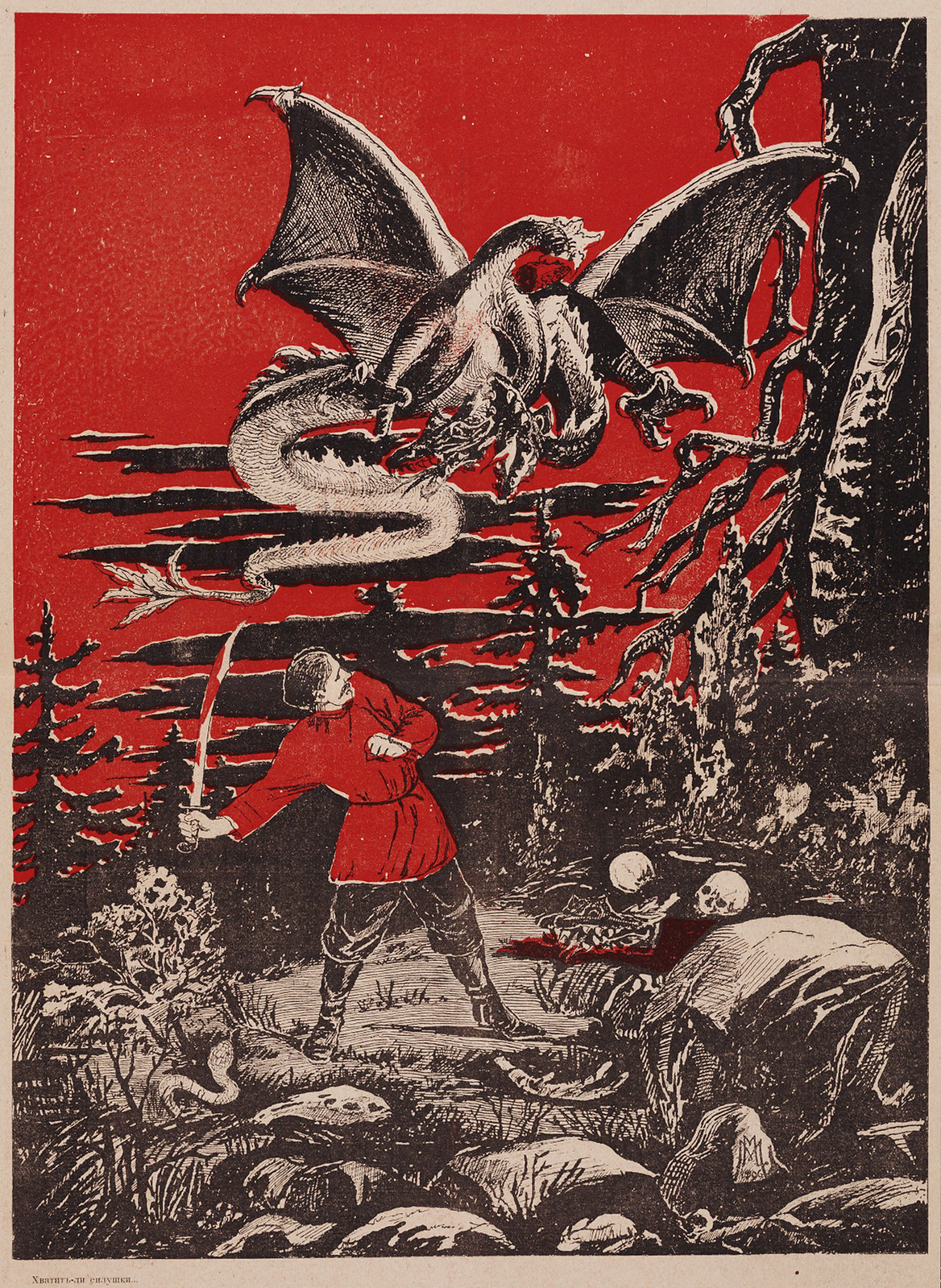

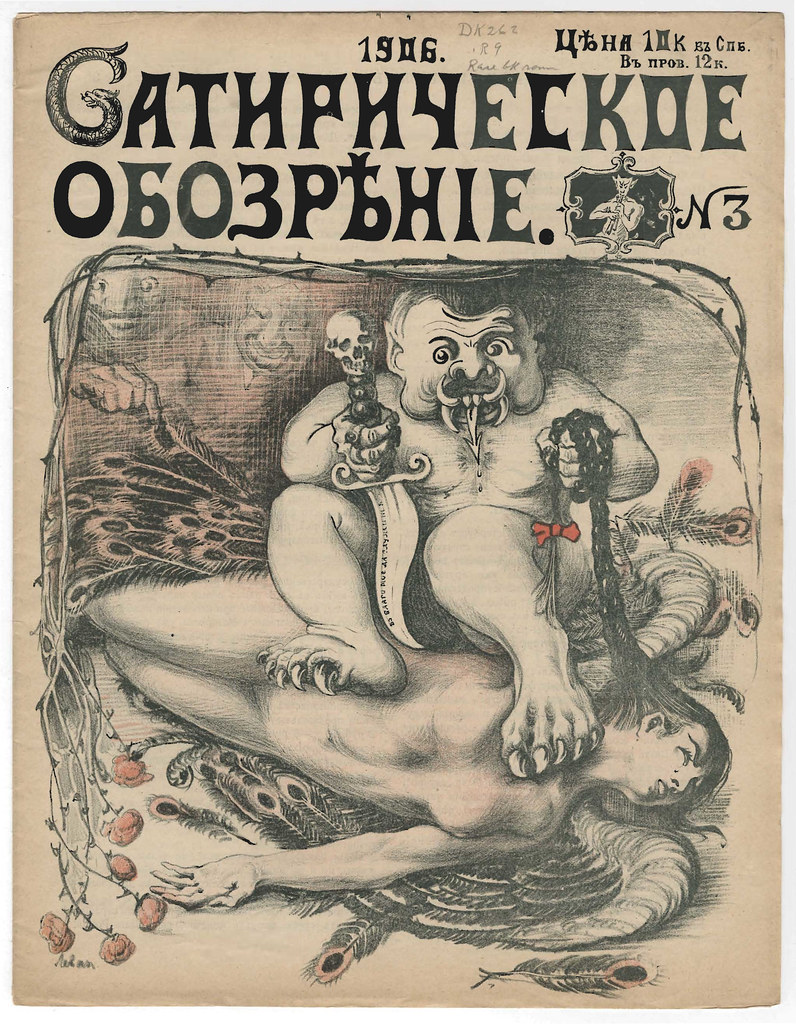

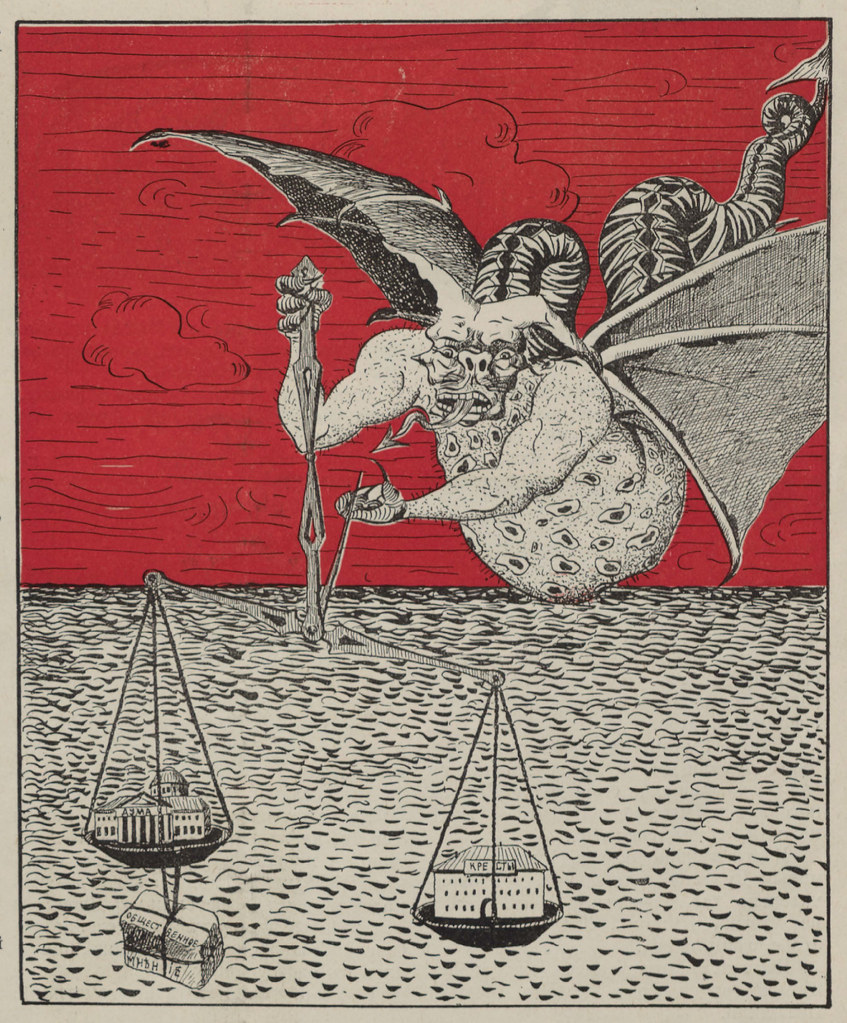

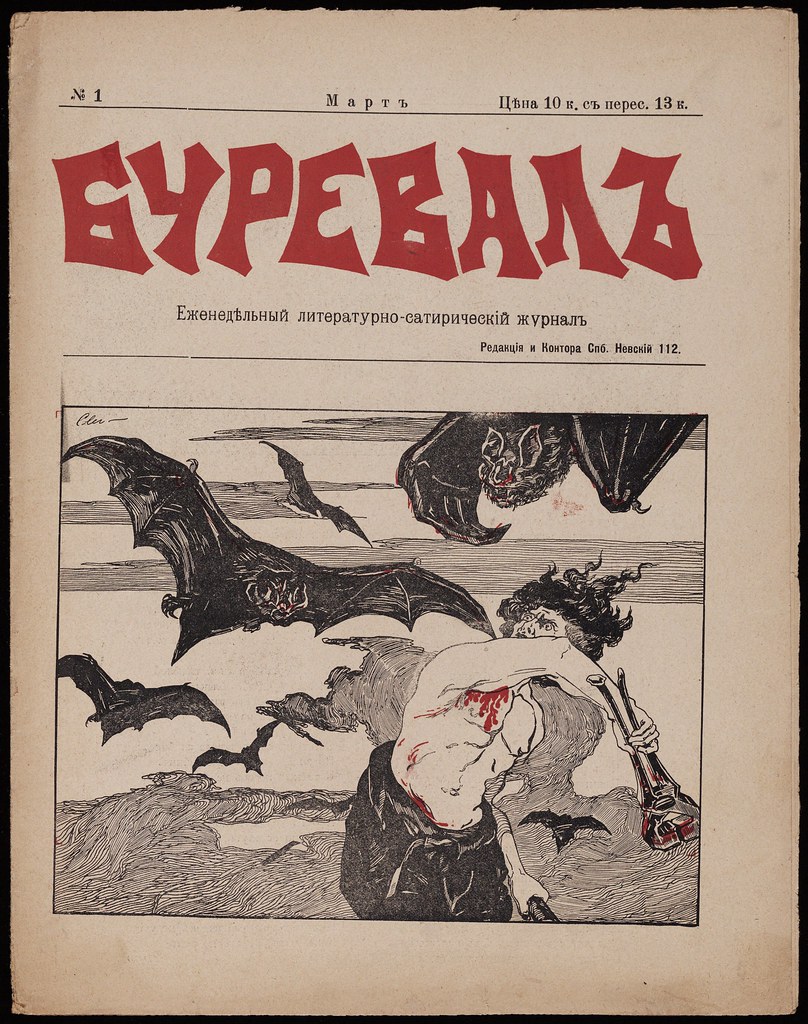

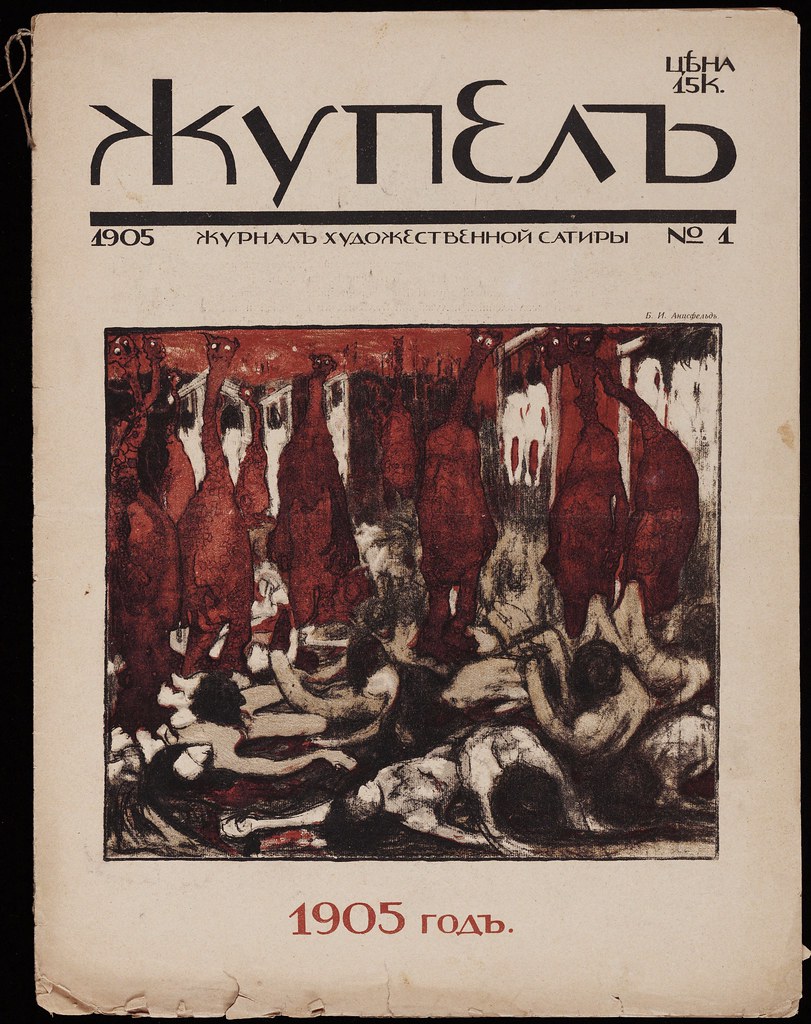

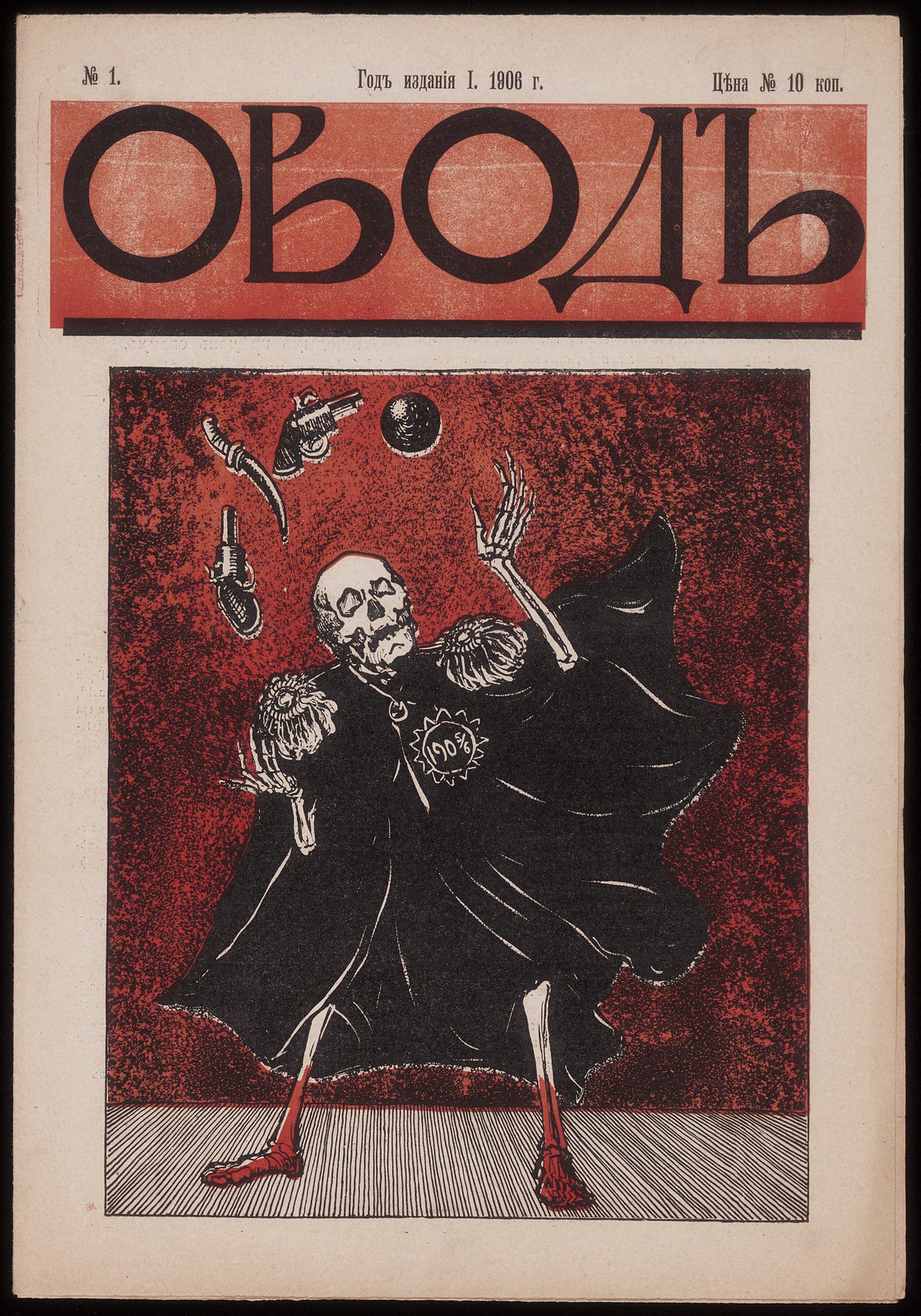

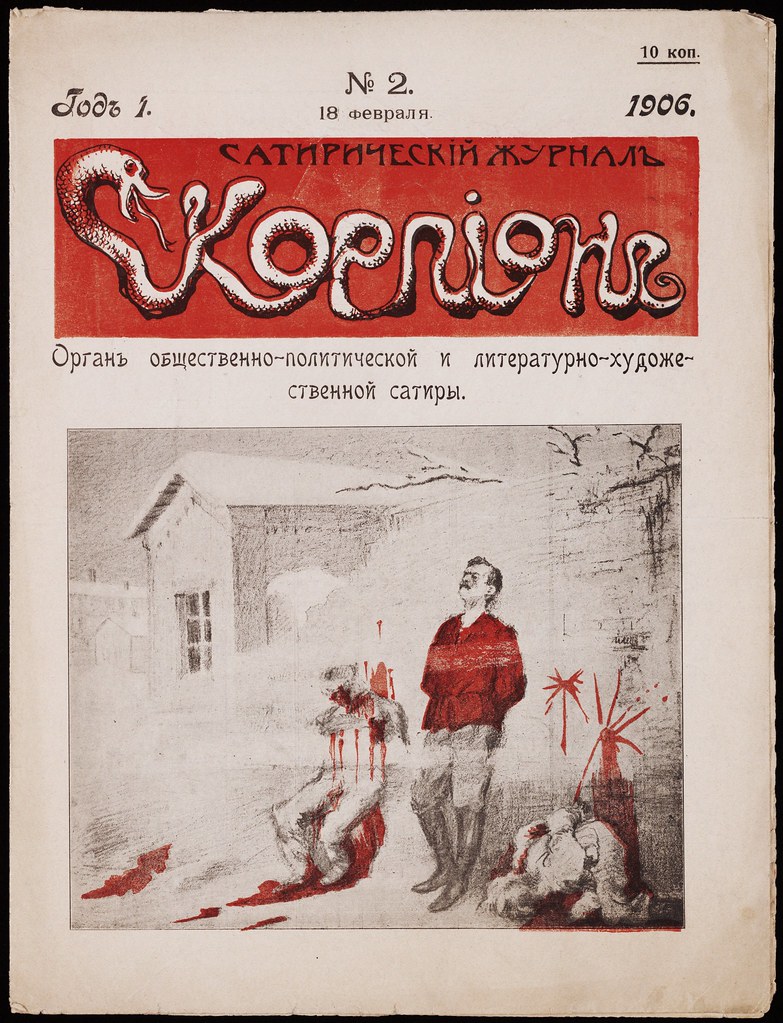

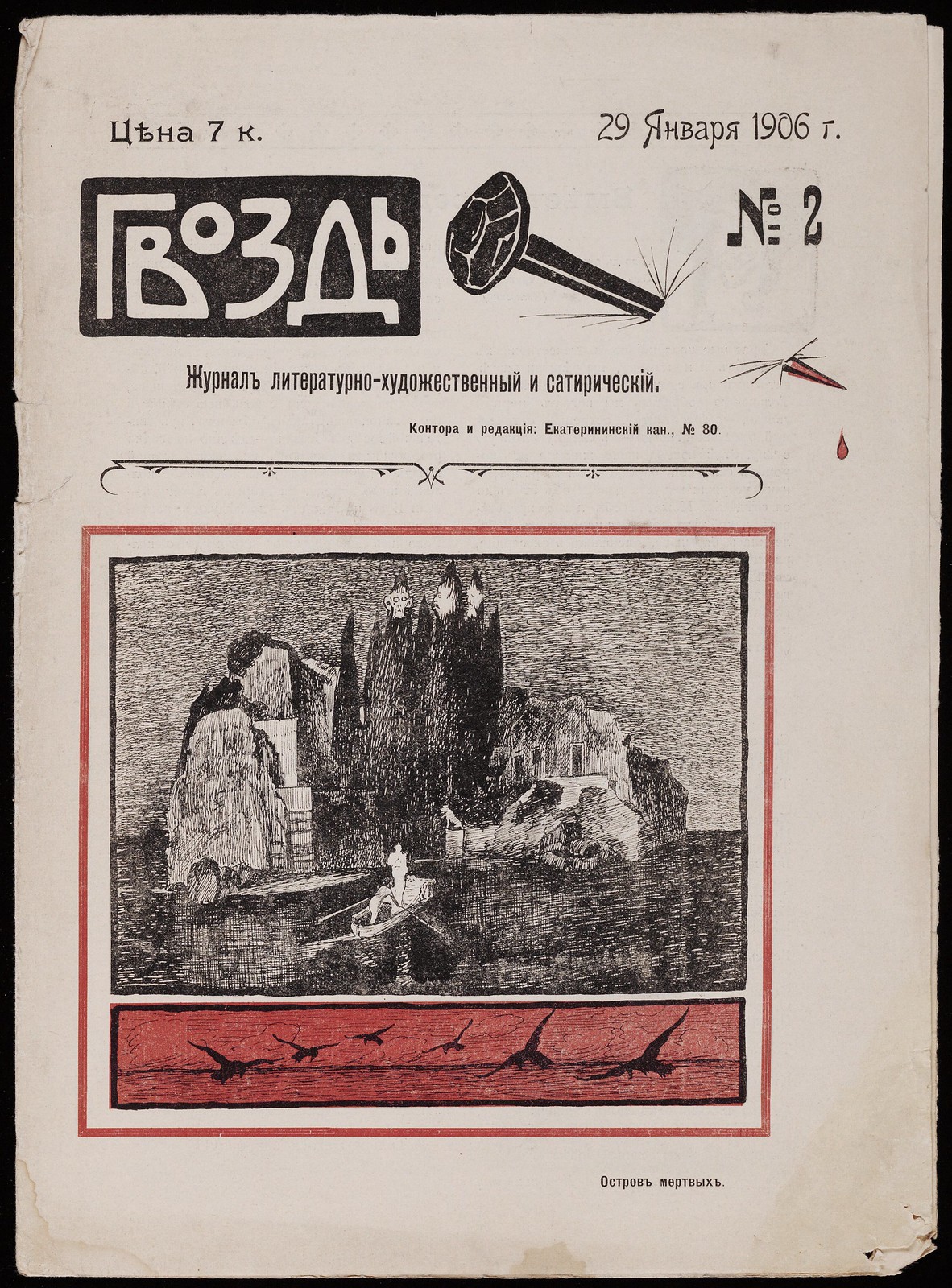

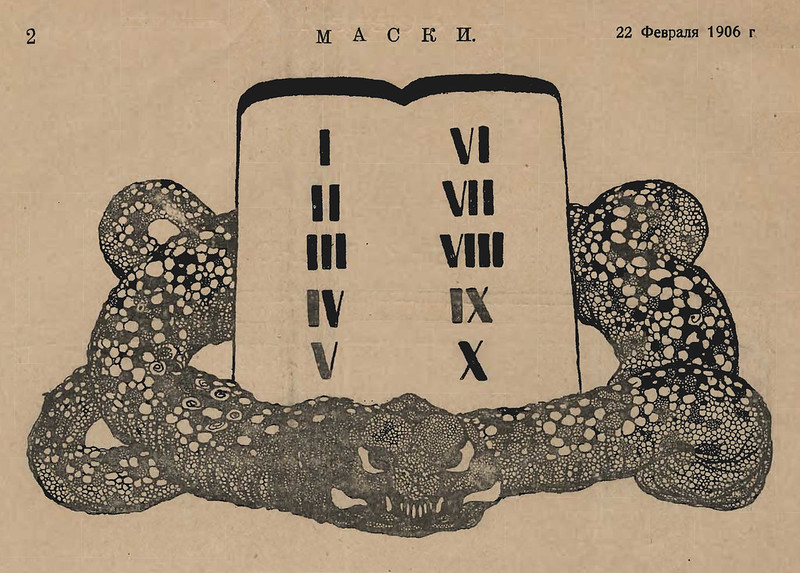

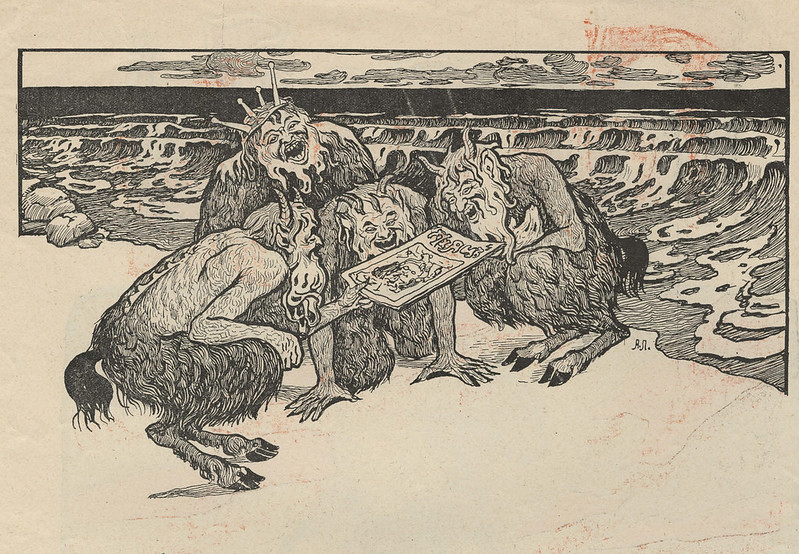

Russian Satirical Journals from the Revolutionary Upheaval of 1905-1907

"This collection documents some of the most important events of the period known as the first Russian Revolution of 1905-1907. It was during this unprecedented rise of national self-identity that the first Russian Constitution and Russian Parliament were initially created. The first Russian Revolution was a period of struggle for political, social and human rights, and the press, which had previously been subject to censorship, enjoyed a new freedom which had never before appeared in Russia.

Nevertheless, disillusionment with the political and social reforms was expressed through political satire and caricature, published in numerous journals all over the country. The pages of these journals served as an arena for political parties and the newly born social classes of Russia – both the bourgeois and the workers. The explicit satirical form of these publications and their subsequent immediate distribution to interested readers attracted many well-known writers and artists who were either contributors or, occasionally, editors of these journals. The journals in the collection present a unique and sparkling collaboration amongst famous Russian authors such as Konstantin Bal’mont, Ivan Bunin, Maxim Gorky, Aleksandr Kuprin, Valerii Brusov, etc., with the artistic talents of Ivan Bilibin, Boris Kustodiev, Léon Bakst, Valentin Serov, Alexandre Benois, and others.

As the Russian autocracy regained its power, the unprecedented freedom of the Russian press diminished and then vanished. While some journals were published continuously for months afterward, many others were either closed or suppressed, and their editors prosecuted, with the entire publishing run of some issues confiscated and destroyed by the authorities. " - quote source

Images mostly found at USC Libraries.

Fire Beneath the Fen: The Wyrd and the Modern in ‘Robin Redbreast’ and ‘Penda’s Fen’

Mark Sheridan / June 16, 2020

The 1970s have always occupied a grim place in the British imagination. Sandwiched between Harold Wilson’s utopian “Swinging Sixties” and Thatcher’s anti-social eighties, the decade represents a time of tremendous turbulence and change. With the empire in ruins, anti-colonial backlash came home to roost as Northern Ireland descended into civil war and the IRA began its bombing campaign in Britain. The naked enthusiasm of the post-war consensus dissipated, and the battle between labor and industry heated up. Bombs, blackouts, and shortages recalled war-like conditions during a time of supposed peace. Modern scholarship has pointed to an eerie style in British cultural output from the period. From its cinema to its television to its public information films, there pervades a gothic sensibility commonly identified with Mark Fisher’s concept of “hauntology,” the idea that the present state of cultural paralysis is a function of a collective mourning for futures that never materialized.

The 1970s have always occupied a grim place in the British imagination. Sandwiched between Harold Wilson’s utopian “Swinging Sixties” and Thatcher’s anti-social eighties, the decade represents a time of tremendous turbulence and change. With the empire in ruins, anti-colonial backlash came home to roost as Northern Ireland descended into civil war and the IRA began its bombing campaign in Britain. The naked enthusiasm of the post-war consensus dissipated, and the battle between labor and industry heated up. Bombs, blackouts, and shortages recalled war-like conditions during a time of supposed peace. Modern scholarship has pointed to an eerie style in British cultural output from the period. From its cinema to its television to its public information films, there pervades a gothic sensibility commonly identified with Mark Fisher’s concept of “hauntology,” the idea that the present state of cultural paralysis is a function of a collective mourning for futures that never materialized.

The dark and mystic sensibility that emerged from this disruptive and paranoid milieu, now called “folk horror,” manifests a fear of sublimation—the absorption of the individual into the mass, the human into the environment, modernity into the unknown. While the horror of Hammer Films and Roger Corman that had dominated the ‘50s and ‘60s was preoccupied with endless combinations of 19th century gothic, folk horror steps outside time as we understand it, beyond the scope of the human. In the 2010 documentary series A History of Horror, Mark Gatiss outlined a rough canon for this folk horror tradition based on the unholy trilogy of Witchfinder General (1968), The Blood on Satan’s Claw (1971), and The Wicker Man (1973). Intense ideological conflict pervades these stories: Witchfinder General is set in and around the Battle of Naseby, where Cromwell’s revolutionary New Model Army destroyed the veteran feudal forces of King Charles, and tells the story of a soldier who pursues a charlatan witch-hunter across the English countryside. And in The Blood on Satan’s Claw, set around the same time, a secular magistrate must slay a demon summoned from “the forest, from the furrows, from the fields” by the local pagan cult.

These historical tales come at us from the dawn of modern time, in the midst of feudal collapse and the emergence of capitalism. Our heroes are rational, secular agents of the state; our villains the ancient forces of paganistic superstition that batter at the door of our burgeoning technological world. It’s telling that the only film in Gatiss’s trilogy set in contemporary times, The Wicker Man, advances a very different view of the battle between the rational modern and the primordial other. Here, the heroic agent of the state, in this case a police officer, dies alone in the flames of the titular effigy, while the villagers dance in rings around him. Christopher Lee would go on to insist that The Wicker Man was not actually a horror film, an assertion that hints at the sublimation of genre itself, and how this paranoid affect had settled over the British imagination like an eerie fog.

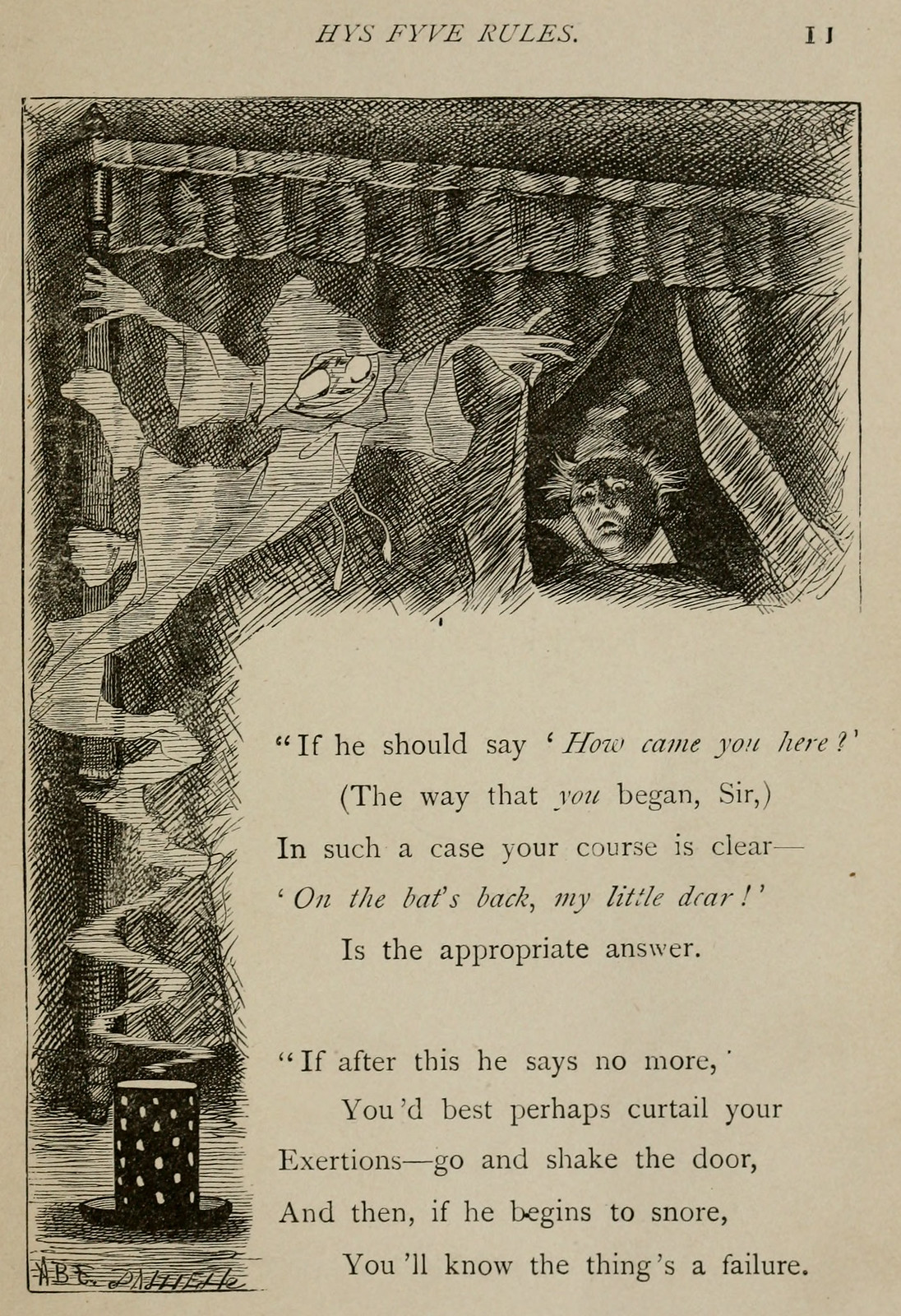

Well before The Wicker Man hit theaters, however, there was the television play Robin Redbreast (1970), which tells a similar story: middle-class metropolitan Norah Palmer (Anna Cropper) ventures into the English countryside only to find herself caught up in the fatal fertility rites of the polytheistic locals. Robin Redbreast is noteworthy for its appearance on Play for Today, a BBC anthology series typically reserved for kitchen-sink realist drama that has been described in posterity as everything from a “national theatre of the air” to an “[exercise] in viewer patronisation” (the latter quote coming from current Conservative Party MP and Boris Johnson ally, Michael Gove). Abrasive, polemical, socially conscious to a fault, its moral messaging embodied the paternalistic spirit of the ‘60s welfare state. If television was the medium of the masses, Play for Today was its conscience.

Set in the present day, Robin Redbreast inverts the conventional relationship between the modern and the un-modern, configuring our world as hopelessly encompassed by a dark architecture of the outside. From the moment Norah arrives in the village, she’s deprived of all agency. Everything she does is preempted, public and private spaces are intermeshed—the villagers always seem to know what she’s doing in advance, repeatedly wander onto her property without invitation, and even orchestrate events so that she ends up sleeping with Rob (Andy Bradford), an awkward local man who she first encounters practicing karate naked in the woods.

Set in the present day, Robin Redbreast inverts the conventional relationship between the modern and the un-modern, configuring our world as hopelessly encompassed by a dark architecture of the outside. From the moment Norah arrives in the village, she’s deprived of all agency. Everything she does is preempted, public and private spaces are intermeshed—the villagers always seem to know what she’s doing in advance, repeatedly wander onto her property without invitation, and even orchestrate events so that she ends up sleeping with Rob (Andy Bradford), an awkward local man who she first encounters practicing karate naked in the woods.

Norah can sense she’s being manipulated in some way but remains powerless to stop it. The menacing Mr. Fisher (Bernard Hepton), apparent leader of the community, even explains their sinister designs, albeit in elliptical language, at various junctures. Yet Norah is unable to resist literal and metaphorical seduction by the strange persuasions of the village folk. There’s a dark implication that in some respect Norah wants, or is at least allowing herself, to be trapped. The heightened emotions of country life contrast starkly against the bourgeois detachment of her conversations with city friends. To an extent, we get the impression that Norah’s volatile relationship with the villagers is a reaction to her own suppressed Dionysian impulses.

The shadowed social commentary is compounded when Fisher explains that the villagers are under no pretense of doing justice to the “old ways.” He admits the basis of the robin sacrifice could be Greek, Egyptian, even Mexican in origin. He mentions James George Frazer’s “The Golden Bough,” a largely discredited work of comparative mythology that serves as the basis for most popular representations of paganism. Historical authenticity is immaterial here. What scares us about paganism is what it tells us about ourselves, how it recalls our own innate strangeness.

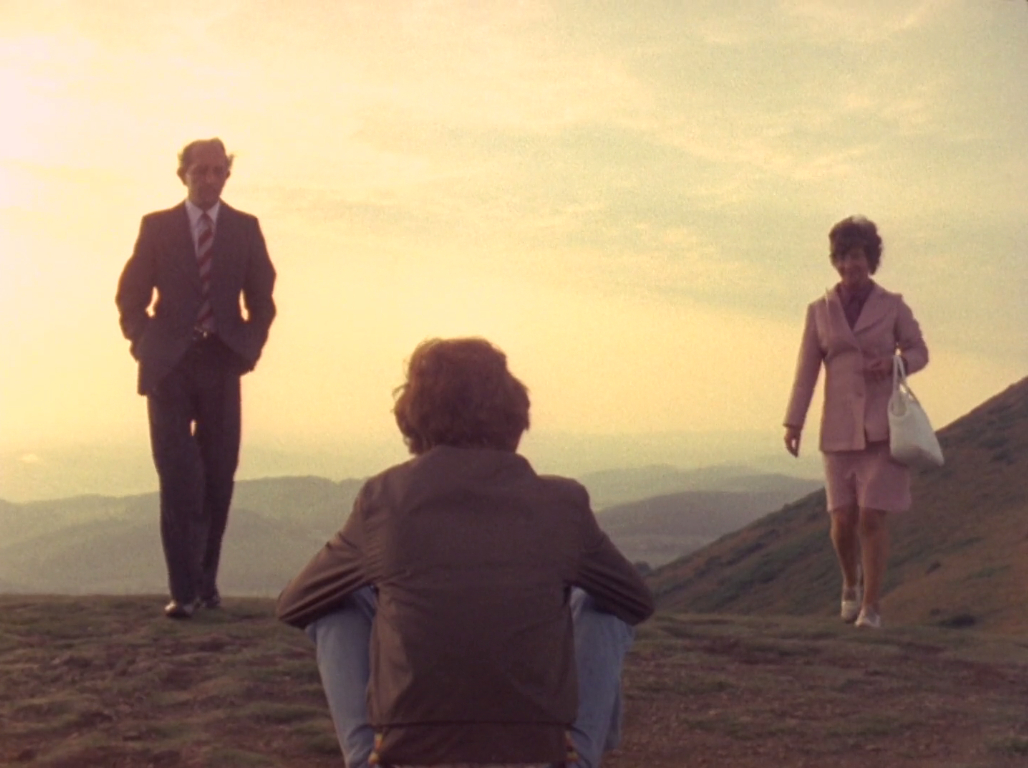

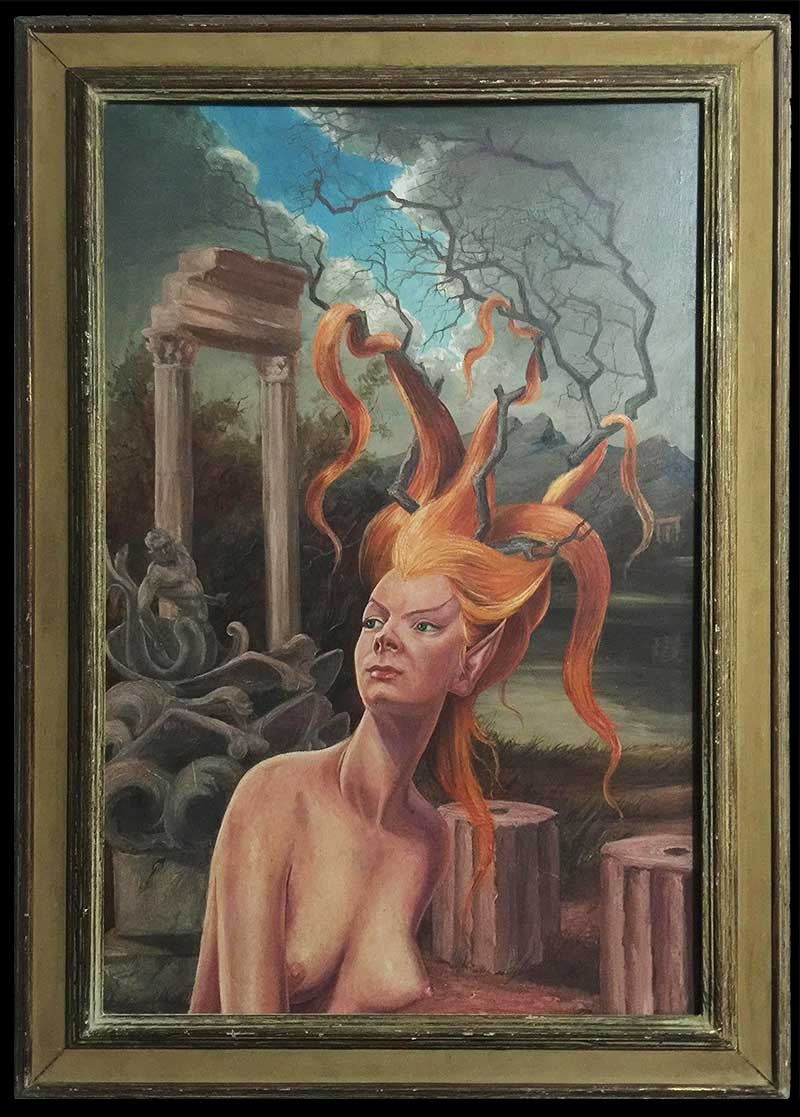

After the ritual slaughter of Rob (short for Robin), a pregnant Norah flees the village, but her escape will never be complete. She knows that the same cycle will repeat itself when her baby, the new robin, comes of age. As she drives away, she looks back to find that the villagers, still watching from the cottage, have transformed into pagan deities. The fact that the villagers do nothing to stop her from returning to the city amplifies the play’s paranoid pessimism. As Fisher, having taken the form of Herne the Hunter, watches Norah disappear over the hill, the viewer is left with the horrible feeling that nothing Norah can do will have any impact on the ultimate fate of her unborn child. (The narrative is clearly inspired in part by Ira Levin’s Rosemary’s Baby).

After the ritual slaughter of Rob (short for Robin), a pregnant Norah flees the village, but her escape will never be complete. She knows that the same cycle will repeat itself when her baby, the new robin, comes of age. As she drives away, she looks back to find that the villagers, still watching from the cottage, have transformed into pagan deities. The fact that the villagers do nothing to stop her from returning to the city amplifies the play’s paranoid pessimism. As Fisher, having taken the form of Herne the Hunter, watches Norah disappear over the hill, the viewer is left with the horrible feeling that nothing Norah can do will have any impact on the ultimate fate of her unborn child. (The narrative is clearly inspired in part by Ira Levin’s Rosemary’s Baby).

Robin Redbreast’s horror is reactive, bird-brained—evoking the feeling of being cornered. The great fear is a lack of control, the feeling of being swept away by strange currents beyond the self. Even in her fleeing, Norah’s fate is ultimately foreclosed by forces that not only surround her but exist elementally within her. If Witchfinder General is set at the dawn of modernity, Robin Redbreast is set at modernity’s dusk, in a world that shrinks from itself as it feels the darkness loom ahead. The postponed reclamation of the robin proves a compelling metaphor for the hopeless uncertainty of a historical moment in which strange futures pounded on the door of the present, threatening to break in at any moment.

* * *The first three years of the 1970s would see five states of emergency, each presided over by Ted Heath’s Conservative government following its surprise election in 1970, and each involving battles between Heath and what Thatcher would later refer to as “the enemy within”—the labor movement. Problems continued to pile up, each new disruption amplifying the last. The stock market crashed in January 1973, sending inflation soaring into double figures; then, in October, OPEC declared an oil embargo that set the western world reeling. Seeing an opportunity, the National Union of Mineworkers voted to go on strike in pursuit of fairer pay. Heath’s government responded by introducing the infamous Three-Day Week, in which consumption of electricity was to be limited to three non-consecutive days per week to conserve coal supplies. For two months, Britain was plunged into a cold, dark winter unlike anything it had seen since wartime.

Described by The Times as a “fight to the death between the government and the miners,” this was the second large-scale confrontation in as many years and one the government couldn’t afford to lose. Heath resolved to call an election to serve as a referendum on the issue of union power, with the Conservatives campaigning on the slogan “Who governs Britain?” The election of February 28, 1974 returned yet another dramatic development: despite the weight of the media and the state behind them, the Conservatives had in fact lost ground and handed the Labour Party a plurality in parliament. A settlement was soon reached in which the strikers secured a 35% pay-increase—the miners had won, at least for now.

Two weeks after the lifting of restrictions, millions of Britons tuned in to BBC1 to watch the latest installment of Play for Today. That evening’s episode was Penda’s Fen, a fittingly unsettling exploration of unsettling times, the most developed folk horror film to date, and a triumph of public programming in its own right. Writer David Rudkin gives voice to the dark song of the fields with a visionary script about a devout young Christian who must confront both the unseen forces that stir beneath the village where he lives and the “unnatural” desires that emerge contrary to his pious pretensions.

Two weeks after the lifting of restrictions, millions of Britons tuned in to BBC1 to watch the latest installment of Play for Today. That evening’s episode was Penda’s Fen, a fittingly unsettling exploration of unsettling times, the most developed folk horror film to date, and a triumph of public programming in its own right. Writer David Rudkin gives voice to the dark song of the fields with a visionary script about a devout young Christian who must confront both the unseen forces that stir beneath the village where he lives and the “unnatural” desires that emerge contrary to his pious pretensions.

Stephen Franklin (Spencer Banks) is a boy possessed by the “new gods”—he is ordered, anal, orthodox, patriotic, loyal to the structures of church and state. He’s the kind of kid that almost deserves the vicious bullying he gets from his grammar school classmates. As Stephen matures into his eighteenth year, however, things fall apart as he discovers that he’s both gay and adopted. Through the mentorship of his heretical parson father, a politically radical local playwright, and a series of disturbing apparitions, he begins to come to terms with his inner “ungovernableness.”

Director Alan Clarke, Britain’s mirror-holder-in-chief behind such brutal portraits as Elephant (1989) and Made in Britain (1982), presents an image of Britishness that’s wild, diverse, almost ethereal. Clarke, typically known for his uncompromising realism, adopts a more hallucinogenic style to portray the metaphysical turbulence of Stephen’s new understandings. The haunted, shifting landscapes of Worcestershire work as a kind of demonic mutation of Situationist psychogeography. Whereas the students of May 1968 were implored to uncover “the beach beneath the streets,” Clarke and Rudkin invite us to discover the flames beneath the fen.

Penda’s Fen stands apart from other artifacts of the “wyrd” in its overt politicization of strangeness. Almost immediately we meet the playwright Arne (Ian Hogg) as he puts up a one-man defense of the strikers at a town hall debate, while naïve Little Englander Stephen huffs and puffs in the audience. As Stephen begins to lose, or rather relinquish, control of himself, his grades suffer and his mother warns him not to fall foul of “the machine,” the inhuman conveyor belt of modernity and its cult of productivity. Later, the Reverend Franklin (John Atkinson) expounds on Moloch as the sun sets behind him, explaining to Stephen how the new gods of industry and institutions are perversions that have disfigured the message of the “revolutionary” Jesus. The Reverend speculates that the people may “revolt from the monolith and come back to the village,” noting that “pagan” means “of the village,” contrasting with what it means to be “of the city”—”bourgeois.”

The provisional nature of modernity is a key theme. Arne speaks of the urban behemoth swelling to a great city that will “[choke] the globe from pole to pole” but that will also “bear the seed of its own destruction.” We might imagine Hobbes’s Leviathan, bloated and turgid, decomposing back into the earth. Elsewhere, Stephen and his father discuss King Penda, the last pagan ruler of Britain. The Reverend reimagines the heretic as a transcendent symbol of resistance, wondering aloud what secrets he took with him when he fell. “The machine,” like the meaty bodies of its busy multitudes, is imagined as just one combination among an infinite number, an entirely temporary arrangement destined for the dirt.

The provisional nature of modernity is a key theme. Arne speaks of the urban behemoth swelling to a great city that will “[choke] the globe from pole to pole” but that will also “bear the seed of its own destruction.” We might imagine Hobbes’s Leviathan, bloated and turgid, decomposing back into the earth. Elsewhere, Stephen and his father discuss King Penda, the last pagan ruler of Britain. The Reverend reimagines the heretic as a transcendent symbol of resistance, wondering aloud what secrets he took with him when he fell. “The machine,” like the meaty bodies of its busy multitudes, is imagined as just one combination among an infinite number, an entirely temporary arrangement destined for the dirt.

Landscape is a focal point of the play but, unlike in our other examples, here serves as a vector of elemental truth rather than a source of corruption. Rudkin draws on the Gothic and Romantic traditions to conjure up an English countryside pregnant with ancient histories that lie unknown, hidden or forgotten. It was here, after all, in the 16th century, that the machine first emerged out of the fields and the fens and separated the peasantry from the land—the original trauma that encloses the margins of modern Western history. What lies beyond that temporal boundary is the vanishing realm of nightmare, of un-modernity, where yawns the black abyss of the unknown, the domain of animal and reigning wilderness. But, paradoxically, that abyss is essential to our nature—it’s where billions of lives were lived, where our minds and bodies were wrought and cultivated. Penda’s Fen considers the abyss for all its hidden potentials and reconfigures rupture as opportunity. The horror of recognizing the self in the other, or vice versa, is imagined as a route to emancipation.

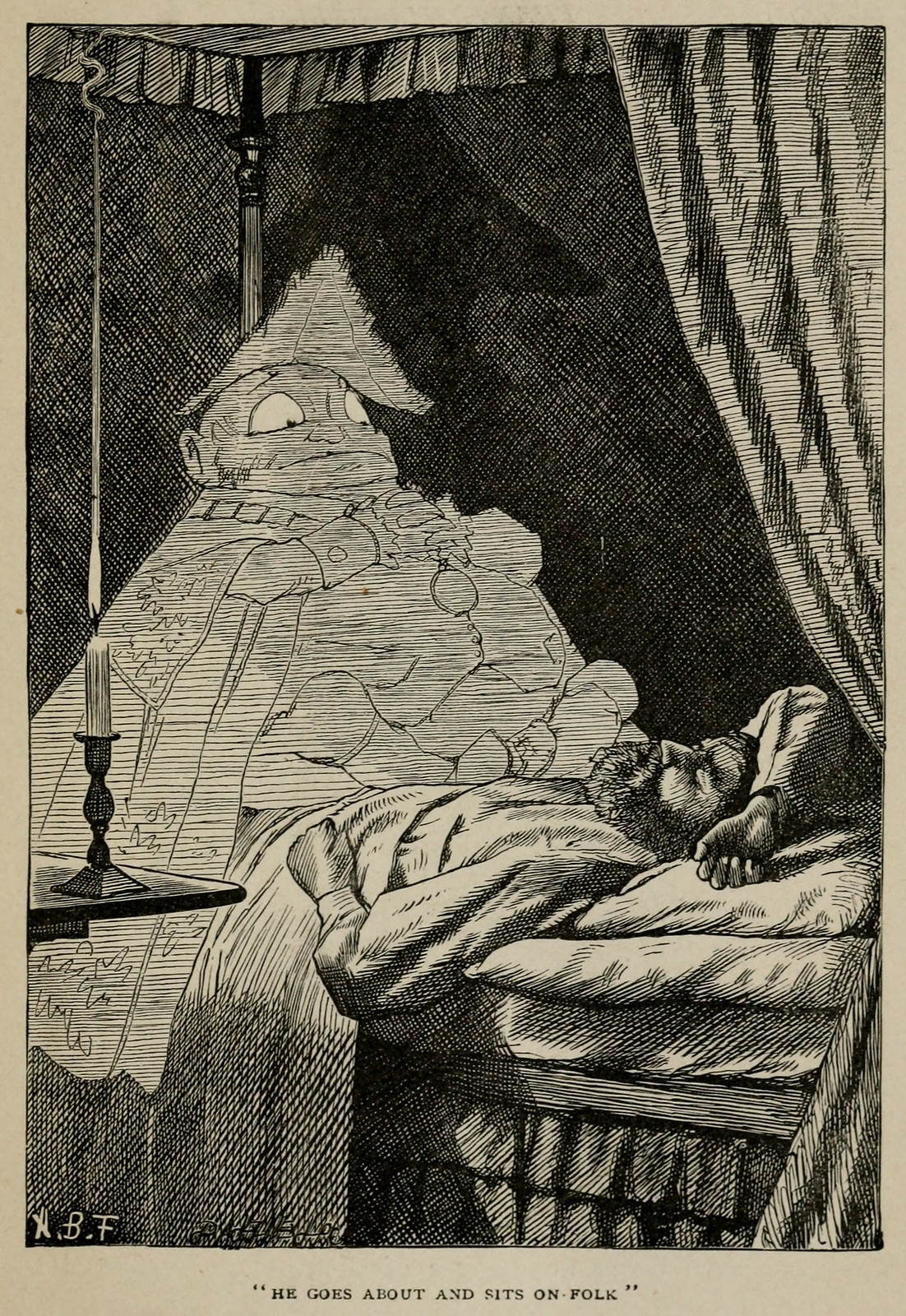

In perhaps the most famous scene, Stephen awakes from a homoerotic dream to discover a demonic entity straddling him in his bed, which then takes the shape of the local milkman (Ron Smerczak). What haunts him is not his sexuality but his dedication to the authoritarian norms of middle-class Protestant England. As Arne prophecies in a later scene, the only way to purge ourselves of these demons and reach salvation is by way of “chaos” and “disobedience,” to summon our basest selves.

In perhaps the most famous scene, Stephen awakes from a homoerotic dream to discover a demonic entity straddling him in his bed, which then takes the shape of the local milkman (Ron Smerczak). What haunts him is not his sexuality but his dedication to the authoritarian norms of middle-class Protestant England. As Arne prophecies in a later scene, the only way to purge ourselves of these demons and reach salvation is by way of “chaos” and “disobedience,” to summon our basest selves.

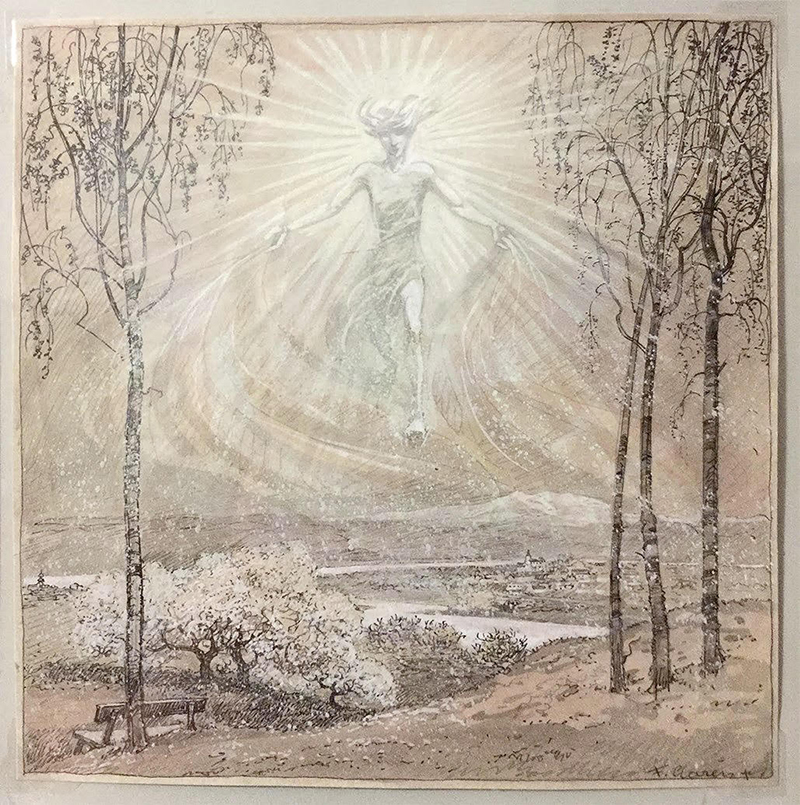

When we first find Stephen, he’s alone in his room, listening to his favorite composer Edward Elgar’s The Dream of Gerontius and reflecting on the moment when the protagonist meets God. Stephen is isolated from the world, only able to theorize obliquely about transcendent experiences. By contrast, the final sequence sees him meet his maker on an open hillside—not God, per se, but King Penda himself, the half-real spirit of “ungovernableness,” who tells him to go forth and “be strange.”

Much like its predecessors, the play makes no attempt at an authentic depiction of pre-Christian spirituality—we have no idea what the titular King Penda might have believed, what his traditions were, what cosmologies were lost when he was defeated all those years ago. But this is precisely the point. The last pagan king functions as an empty vector of “possibilities” and “unknown elements,” much like Stephen himself. Despite being an apparition of a long-dead historical figure, King Penda represents a haunting from the future, that dark domain of the beyond with which we are in contact every moment of our lives, full of unthinkable potential and inherent strangeness.

Penda’s Fen advances itself as the spiritual resolution to the folk horror cycle, a psychic exorcism of the demons that haunted the ‘70s. Rudkin’s play summons the future from the past, reconstituting the volatility of its day as a rite of passage into a new world. Horror in this sense denotes contact with new terrain, communion between the self and the beyond. To be comfortable is to live in fear of the strange invasions that confront us at every moment and in every thought and experience—to flee from ourselves. In a time when people want change without having to confront the proverbial milkman, the play enjoys continued relevance long after its first life.

Both Robin Redbreast and Penda’s Fen were aired only once more on British television, in 1971 and 1990 respectively, lending these tales the ephemeral quality of weird dreams dreamt long ago—and raising the question of why they’ve now returned to haunt us. The villagers never came to reclaim the robin in the end, yet still we see their shapes in the window and hear strange knocks at the door. Will we ever face up to the horrors that guard the margins of our world? Or are we, like Norah Palmer, doomed to retreat further and further into the city, to delay the inevitable day when the outside closes in? In the closing scene of Rudkin’s play, King Penda prophesies exile as the sun sets behind him: “Night is falling; your land and mine goes down into a darkness now… but the flame still flickers in the fen.” The future promised by that strange flame lies lost somewhere in that expanse of night. Only by embracing the dark might we find it again.

![]() Mark Sheridan is a writer from Dublin, Ireland. He recently graduated from Dublin City University.

Mark Sheridan is a writer from Dublin, Ireland. He recently graduated from Dublin City University.

draconym: A mermaid is just the lindworm of the...

“Fact—Not Fiction”: UFO Journals from the Archives for the Unexplained

Michael Grasso / May 28, 2020

Detail from cover of issue No. 1 of “Mysteria,” a German “trade magazine for UFO research and ancient astronautics.”

Part of the “unprecedented” reality that humanity has been experiencing the past couple of months has been the way this pandemic has scrambled one’s normal cognitive pathways. Putting aside how badly my remotely-diagnosed COVID infection last month sent me into a deep spiral of brain fog, even since recovering from that misery I haven’t been able to concentrate on much. For a while, reading anything more complicated than a comic book was completely beyond me. And even as I’ve been slotting longer books back into my everyday routines, it’s been nearly impossible for me to write. Even when I find a topic that speaks to me, every single piece I’ve tried to start has withered on the vine. “Why bother?” I find myself asking myself. “Who cares?” Mental illness will steal a lot from you if you are unlucky enough to have it play a prominent role in your life: your time, your pride in your labor, your self-respect, even your friends and significant others. But what it seems to steal from me most often—even under “normal,” non-pandemic circumstances—is joy, the joy of discovering something amazing and getting to share that discovery with others. With existential anxiety stalking the human race along with this deadly virus, those simple pleasures of life have been so hard to find.

So when I was reminded last week of a link to an amazing archive of UFO organizations’ publications and zines hosted by the Archives For The Unexplained of Norrköping, Sweden, I was gifted with a brief afternoon of respite, a momentary return of long lost joy. When I’d first glimpsed the archive back in October of last year, I had a brief breeze through it. I was overwhelmed by the variety and relatively secure in the possibility that it would be there if I ever wanted to revisit it. This month, the archive was there for me when I needed it. I discovered over the course of that afternoon that this collection’s cockeyed series of hand-drawn flying saucer encounters and alien visitors, its poorly mocked-up layouts and headlines, its entirely sui generis outsider art vibe—all of it was medicine for the despair and crushing lack of a hope that was ailing me.

I think part of the profound impact of this archive is the way I found it, from an off-handed mention in a tweet that had made its way to me through academic folklore studies circles. But it’s often those accidental discoveries that have sent me down the most satisfying paths while I’ve been writing for Mutants. It’s how I discovered video of the uncanny Nebraska PBS performance by Entourage: after reading a Pitchfork review of a reissue of their albums. It’s how I discovered so many great Mutants exhibit subjects on the Internet Archive, and how I discovered yet another inspirational ufological archive, at textfiles.com. So yes, when I rediscovered this archive I dove in head-first, marveling at the dozens of countries these UFO zines came from, the impressive time period they represented (all the way from the 1950s to the 21st century), and the care that had been taken in assembling and scanning them. Since the original link had gone to a featureless web directory page, I never even bothered back in October to investigate fully who had collected and assembled this amazing archive. This time however, that was the first thing I wanted to find out.

As mentioned, this trove of treasure was preserved for posterity by the Archives of the Unexplained in Norrköping, Sweden. Formerly known as the Archives For UFO Research, the organization was founded in 1973 specifically to collect and preserve an archive and library of UFO sightings and ephemera for researchers. It is also connected to one of those very UFO research organizations whose magazines and periodicals I had fallen in love with last October. The AFU’s founders had broken away from a ufological group called UFO-Sweden over differences in “ideology” to found the AFU. By 1986, that rift was reconciled and UFO-Sweden and AFU agreed to a reciprocal agreement of support that would see AFU preserve UFO-Sweden’s archives full of materials from over a hundred local UFO-Sweden groups. But AFU preserves far more than materials from its native Sweden. UFO documentation from dozens of countries finds representation in both its material and online archives.

And that sort of local, bespoke interest in UFOs is precisely what makes AFU’s archive of magazines so special. I of course restricted myself to UFO zines produced during our usual Cold War period in preparing this piece, but you can find plenty of later material from the dawn of the home computer “desktop publishing” era of the ’90s and beyond. Needless to say, while they have their own charming aesthetic, I was won over by the hand-layout and manifold typewriter typefaces of the zines from the 1950s to 1980s. Some of the covers of these periodicals, especially the ones produced in the 1950s, display a strikingly professional sense of artistic composition on par with their bigger competitors of the early UFO era, such as Fate magazine. Of course, the AFU magazine archive is far too vast for me to give a review of every single periodical in there. But despite the startling diversity, both culturally and philosophically, on display, it’s the commonalities between all these organizations that pleased me the most. While the magazines themselves vary—from very simple typewritten and mimeographed/photocopied bulletins to quite professionally-produced full-color magazines—the common thread linking these publications is their passion and obsession for a subject that, one senses after reading a few of the articles and editorials within, has largely left them on the outside of the mainstream.

Because despite some of these publications representing the official organs of “national” UFO organizations like UFO-Sweden, the vast majority represent UFO aficionados on the state/provincial/county/city level. You may well wonder if there was enough content to keep a magazine like “Merseyside UFO Bulletin” or “UFO-Quebec” or the “Sri Lanka UFO Register” going for longer than a couple of issues, but even some of these smaller local publications went on for a decade or more! And in the archives of each, you get these magnificent glimpses of local culture, UFO or otherwise. I had a blast reviewing the archives of the two-page MUFON Massachusetts newsletter from the early 1980s, of course, a time and place where I myself was getting deeply into ufology as a little kid. Seeing the quotidian details of the Mass. MUFON group—their fundraising efforts, convention organizational efforts, meeting minutes, appearances on local Boston television (these were especially exciting for me, of course), and indeed the gradual maturity of their merrily amateurish newsletter layout skills—sent me back in time and made me feel like I was part of the team. On the flip side, you have more eerie dispatches from the past, such as the silent testament of the brief run of UFO Chile abruptly ending in May of 1969—poignant because we know what transpired a few short years thereafter.

These are mostly small clubs of like-minded individuals, all doing their best to keep track of local UFO happenings and dutifully preserving those records for posterity. And on the masthead of a majority of these zines, in all the languages of the world, there is a consistent clarion call: please make contact. Not a message to our alien visitors, mind you, but to the publishers and clubs of enthusiasts all over the world. Please reach out, please make a connection. Several of the publications in non-English-speaking nations produced separate English-language editions of their bulletins expressly for this purpose. And I think this aspect of the AFU archive is why it spoke to me so deeply and meaningfully in a time of quarantine and lockdown. Here is a global subculture, in the days before wide adoption of the internet, which ends up assembling and organizing itself in a modular, fractal, rhizomatic manner. Here, despite all odds and with very little in the way of resources either professional or financial, small groups banded together over a shared occult interest, one that likely exposed many of their members to mockery and derision. They not only found each other on the local level but produced collectively a massive, tangible archive that serves as a testament to a Cold War-era social phenomenon. It is an archive with real, profound historical value.

These magazines reached across the oceans and continents in a time when the only means of communication UFO enthusiasts had at their disposal were the national postal service and maybe some stolen Xerox machine time at the office. A sense of community, however dispersed and fragmentary, was what these ufologists really sought—the visitors in flying discs are almost incidental. One wonders if the lesson of the UFO craze is not its possible origins as an intel operation meant to distract citizens of the West from experimental machines of war, but instead perhaps its subsequent co-optation by ufologists into an exploration of the potential of global togetherness and understanding. It’s an historical example of a kind of virtual community spontaneously forming, triumphing over distance and very long odds, that really hits home at a time when we’re all lucky enough to have a global communications network at our disposal, and yet are still somehow feeling only tenuously connected to each other. In these wonderfully weird artifacts of the past, we gain a new perspective on community for our increasingly troubled present.

![]() Michael Grasso is a Senior Editor at We Are the Mutants. He is a Bostonian, a museum professional, and a podcaster. Follow him on Twitter at @MutantsMichael.

Michael Grasso is a Senior Editor at We Are the Mutants. He is a Bostonian, a museum professional, and a podcaster. Follow him on Twitter at @MutantsMichael.

Debt of Honor: The Complex Reality of 1980s War Comics

Mike Apichella / May 26, 2020

Detail from the cover of The ‘Nam #24, November, 1988

The Reagan-worshiping, Polo-drenched patriotism of the 1980s couldn’t hide the scars left by the Vietnam War. An entire generation grew up with nightly news reports sporting brutal images of guerilla warfare and violent political demonstrations. The confusion left by Vietnam caused moral perceptions of American wars and soldiers to become complicated and uncertain. Cultural ephemera in the ‘80s reflected this ambiguity across all media. More than a decade to meditate on Vietnam through books (Born on the Fourth of July, The Best and the Brightest), film (Coming Home, Apocalypse Now), and both mainstream and underground journalism led to the conclusion that there were no longer concise justifications for large scale armed conflicts. Even garden variety action fare like the Rambo films and the A-Team TV series had protagonists embodying the “crazy Vietnam vet” stereotype.

Objective definitions of right and wrong attached to previous “popular wars”—especially World War II, which gave rise to the first war comics and mass-produced war toys—no longer applied. Trusted storytelling tropes faded away as war’s questionable nature became a muse for artists seeking to portray the reality of battle minus vainglorious machismo and nationalism.

‘80s comic books were no different than any other medium. Marvel Comics’ The ‘Nam, DC’s G.I. Combat and Weird War Tales, and Charlton’s Battlefield Action eschewed “feel good” war stories in order to focus on the far-reaching consequences of physical violence, the shifty political motives of the Cold War, and the universal philosophies that define military service. With the exception of The ‘Nam, most mainstream ’80s war comics were created by artists who were WWII veterans and aging members of the “Greatest Generation.” Even though they never made overt anti-war propaganda, Sam Glanzman, Robert Kanigher, Joe Simon, Jack Kirby, Joe Kubert, and many others went out of their way to present war as a negative element of society. There’s nothing cold and heartless about their work, but there is always a sense that something is being held back. While The ‘Nam was biting anti-war criticism, the rest of these books gave voice to the confused masses who had yet to take a side in the struggle for peace.

The quintessential ‘80s war comic is the 255th issue of DC’s anthology title G.I. Combat. The series began publication in the ’50s as a conventional war book with a clear pro-war stance. During its final years it developed a much more nuanced perspective. The Joe Kubert cover art for #255 shows a grisly flaming skeleton dressed in a soldier’s uniform standing in the turret of a tank as two helpless infantry men look on, consumed by horror and fear. Before you even open to the first page it’s clear that American military might will not be this issue’s dominant theme. The burned up corpse comes from the book’s final story, “Dead Letter Office,” by Robert Kanigher and Sam Glanzman. By the time of the issue’s winter 1983 publication, Kanigher and Glanzman had become sequential art’s premier war story team, with careers that spanned more than 40 years in mainstream comics.

The quintessential ‘80s war comic is the 255th issue of DC’s anthology title G.I. Combat. The series began publication in the ’50s as a conventional war book with a clear pro-war stance. During its final years it developed a much more nuanced perspective. The Joe Kubert cover art for #255 shows a grisly flaming skeleton dressed in a soldier’s uniform standing in the turret of a tank as two helpless infantry men look on, consumed by horror and fear. Before you even open to the first page it’s clear that American military might will not be this issue’s dominant theme. The burned up corpse comes from the book’s final story, “Dead Letter Office,” by Robert Kanigher and Sam Glanzman. By the time of the issue’s winter 1983 publication, Kanigher and Glanzman had become sequential art’s premier war story team, with careers that spanned more than 40 years in mainstream comics.

“Dead Letter Office” is a seven page tale about Army Captain J.J. Jamison, a World War II officer assigned the thankless, heartbreaking job of composing letters to combat fatalities’ next of kin. It depicts the CO’s angst as he futilely attempts to keep emotional distance from the job while the death toll symbolically piles up in his office (nicknamed the dead letter office). Day after day stacks of casualty reports spill on to Jamison‘s desk, overflowing with all the warm sentiment of a corporate paper trail.

When a young soldier and his comrades are killed during a fierce tank battle, Captain Jamison suffers a moral crisis while attempting to write a letter that gives the soldiers’ story a heroic spin. It feels like Kanigher and Glanzman are describing themselves when they reveal the captain’s plight as a messenger who must document gory death in patriotic language that’s socially acceptable—or bear the burden that comes with an uncensored account of war’s power to twist bodies and minds beyond recognition.

Many of the latter G.I. Combat stories are poetic and heartbreaking, but none more so than “Debt Of Honor,” another Kanigher/Glanzman piece and the opening tale in G.I. Combat #255. Spoilers abound in any attempt to sum it up, but it’s safe to say that the hardest hitting element is the story’s ability to convey tragedy without visuals, a breathtaking feat for a medium driven by illustration. In “Debt Of Honor,” the reader’s own preconceived notions of violence, evil, love, reverie, and loss serve the same purpose as a pen, a pencil, or a typewriter. The story’s tragic elements are as old as war itself, and they remain as relevant now as they have always been.

A few months after G.I. Combat #255 hit the newsstands, Charlton Comics published the 83rd and 84th issues of their war anthology Battlefield Action. The two comics were entirely comprised of true stories written and drawn by veterans of World War II and the Korean conflict. These originally appeared in the pages of an innovative but obscure 1950s comic book called Foxhole, whose primary creators were none other than comics legends Jack Kirby and Joe Simon. In the ‘80s, Charlton was the biggest little indie publisher in the business, barely staying afloat financially and mainly reprinting material from their halcyon days. Even within a glut of reprint books, these Foxhole stories were exceptional. First and foremost, prior to the publication of Battlefield Action issues #83 and #84, the company had never made a focused effort to reprint material from one specific war series. Charlton’s creative core at the time included editors George Wildman (a veteran of both WWII and the Korean War) and Bill Pearson, a multimedia artist who got his start as a fanzine contributor for the Wally Wood publication witzend.

Battlefield Action #84, December, 1983

It’s anyone’s guess as to why Wildman and Pearson felt these books deserved a retrospective, but there’s no doubt that Foxhole didn’t get a fair shake in its original run. Early issues of the title appeared in 1954 and were published by Mainline, one of the many comic book companies whose sales were crushed by the censorship and witch-hunt tactics of child psychologist Frederic Wertham and his infamous anti-comic book rant Seduction Of The Innocent (1954). When Mainline went under, Charlton swooped in to scavenge the copyrights of their unpublished comics, which in the case of Foxhole applied to the last three issues of the series. Like The ‘Nam, Foxhole presented a distinctly unglamorous vision of war. Because it centered around WWII and the early days of the Cold War, the title had no acidic streak of anti-war sentiment, but nonetheless its stories expressed pain and tragedy in a way that was much more palpable than anything in either The ‘Nam or G.I. Combat. These true anecdotes were illuminated by informality and confessional intimacy. Despite rarely breaking seven or eight pages, they overflowed with character development and nuance.

Foxhole avoided any over-the-top reverence for the American military. It depicted war with stark realism and little else. Consequently, it only lasted for seven issues. Thought provoking stories like Jack Kirby’s “Listen To The Boidie” and Art Gates’ “Kamikaze Joe” struck a chord with fans in the post-Vietnam era, but they were freakish upon arrival in the mid-’50s, a period when G-rated pablum dominated comics as a result of Seduction Of The Innocent.

At the opposite end of the spectrum was Weird War Tales. Like G.I. Combat, this was a long running DC publication. The eccentric comic’s name says it all. The book featured supernatural fantasies set in war time (narrated by The Grim Reaper dressed in army fatigues) and serialized genre mashups starring G.I. Robot and The Creature Commandos. “The Day After Doomsday” was another serialized feature in WWT. Its post-apocalyptic narrative took place during the first days of The Great Disaster (a catastrophe made famous by Kirby in his dystopian DC title Kamandi: The Last Boy On Earth). Throughout its run, “The Day After Doomsday” possessed an emotional complexity identical to that of many ‘80s war comics, even though its first installments were published in the early ‘70s.