Eaten Alive: James Herbert’s ‘Rats’ Trilogy

M.L. Schepps / December 1, 2020

When 30-year-old ad-man James Herbert set out to write a novel, he had a simple goal in mind: “to show you what it was really like to have your leg chewed by a mutant creature.” He succeeded admirably. 1974’s The Rats was a genuine cultural phenomenon upon release, a blockbuster that sold out its initial print run of 100,000 within three weeks and, in the words of The Observer, “irrevocably mutated British horror,” tearing it “from the grip of the bourgeoisie” by “writing about working-class characters” and squaring off against the ugliness and frank brutality of contemporary life.

Herbert would go on to become an author of global significance, his 23 novels eventually selling over 54 million copies worldwide in 34 different languages. He would develop as an author and an activist, tempering the trademark gore with more refined language and higher literary aims. But during his first decade as a professional writer, Herbert excelled at what the British called “nasties,” publishing a novel per year, including two sequels to The Rats that completed a trilogy.

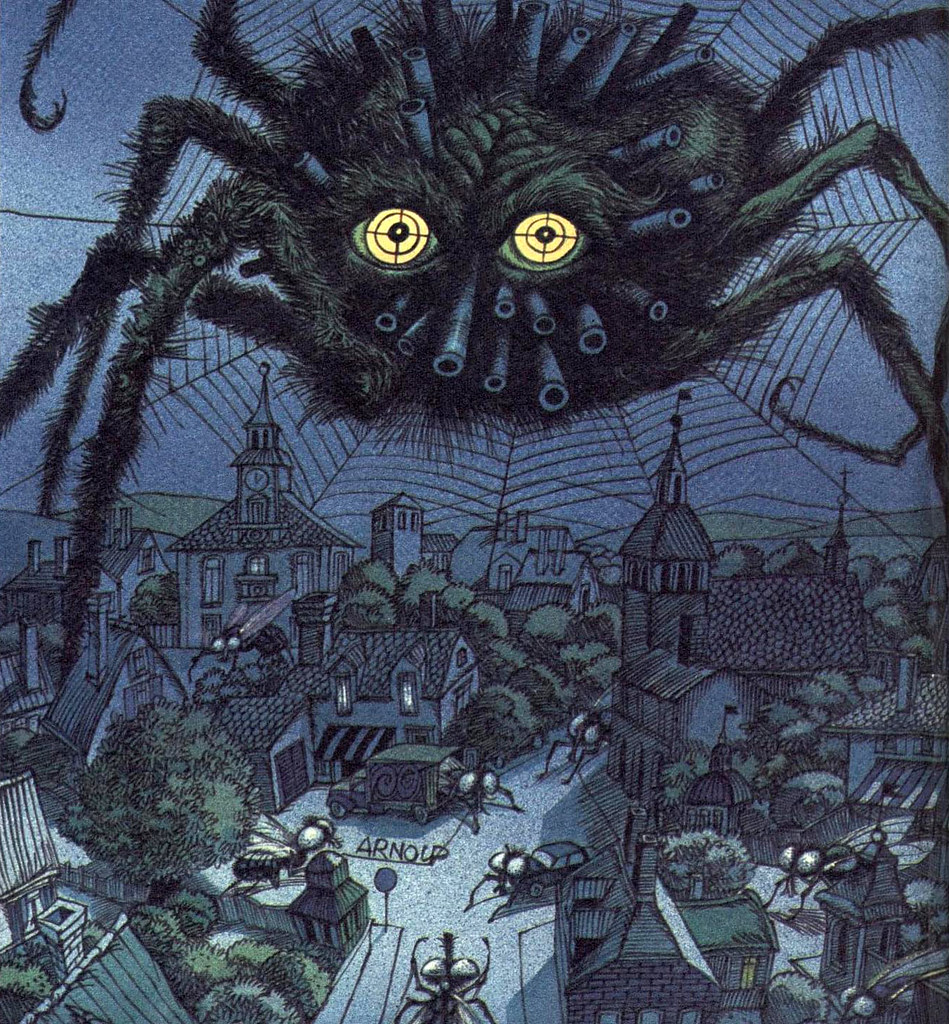

Gory, puerile, and utterly appealing, the Rats trilogy has much to offer the modern eye. In addition to the unnerving horror and gore—neatly scaffolded by clean prose and the occasional purple flourish—we are given a glimpse of a vanished London, a city of vast slums, uncleared bombsites, abandoned docklands, feral children, casual racism, and lusty English perversion—a half-tamed London, not yet leveraged and financialized and vertical, but sprawling, old, and mean.

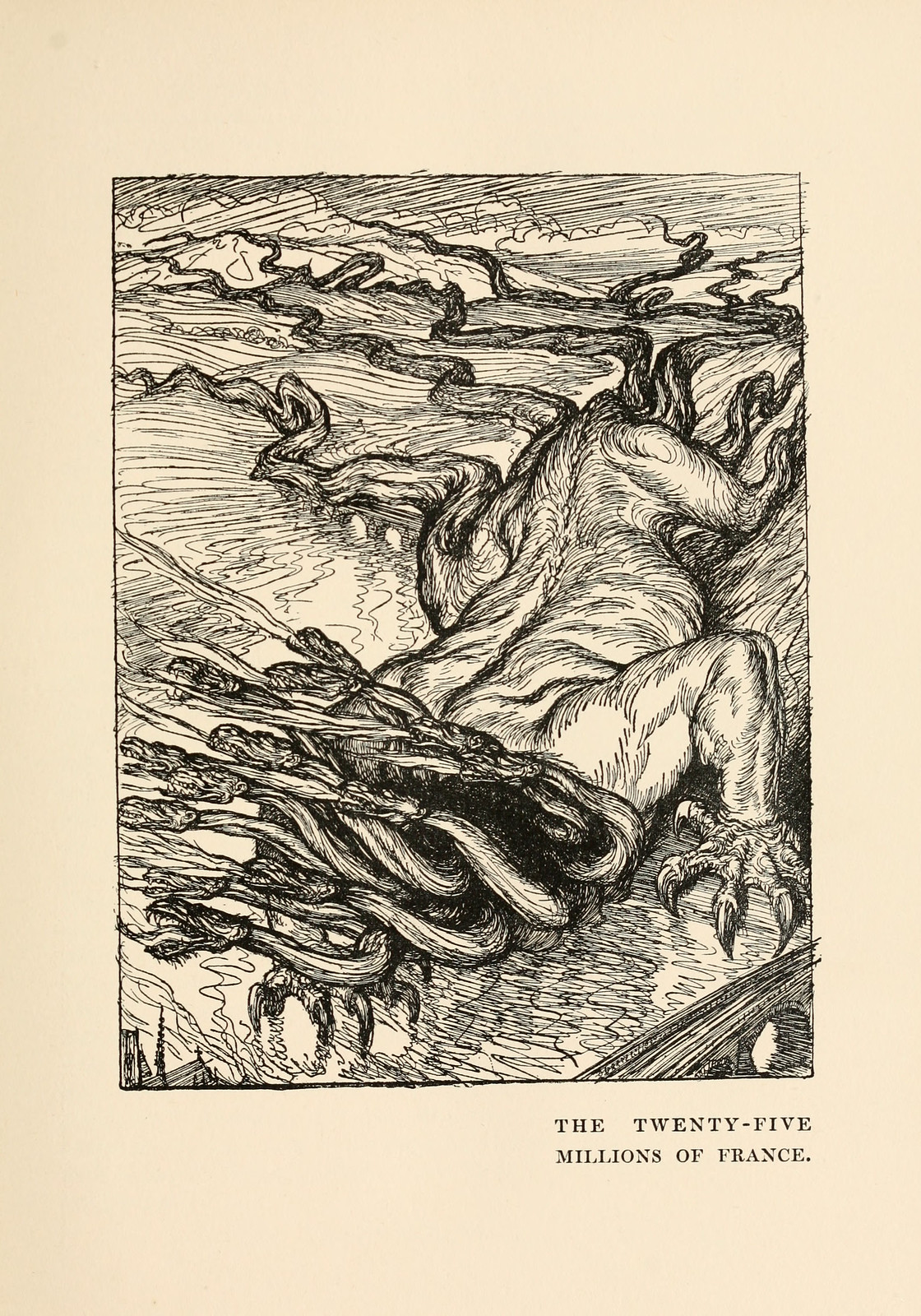

It is this London that James Herbert was raised in, and it is the one he viscerally evokes in the pages of his first novel. The Rats is, in the words of the author himself, “packed with metaphor and subtext.” In a 1993 interview with The Observer, Herbert relays the theme quite plainly: “the subtext of ‘The Rats’ was successive governments’ neglect of the East End of my childhood.” Herbert conjures up the decaying East End, centered around the dying Thames port known as the London Docklands, with righteous indignation. For centuries, the London Docklands were the beating, sclerotic heart of Empire. The wealth and legacy of untold peoples, developed over countless millennia, were ruthlessly extracted by the ships that plied those waterways, amassing vast amounts of cultural heritage, wealth, and treasure in the name of English colonialism while sending out fleets of gunships, grave-robbers, and bankers in exchange.

By the 1970s, however, the area was in a state of absolute collapse. The docklands that survived the transition from East Indiaman to steam to diesel, that survived the Blitz and powered the world-historic growth and exploitation of the British Empire, died as a result of the proliferation and adoption of intermodal shipping containers, which led to larger ships that required deeper ports than the Docklands could offer. Shipping moved irrevocably to provincial centers like Felixstowe or further downstream to the Port of London, leaving the great bulk of the Docklands largely abandoned, the surrounding neighborhoods subject to flight. Between 1976 and 1981, the population of the area was reduced from 55,000 to 39,000.

So, the East End of this period was one of decay and transition. Herbert said that he was raised in “an old slum that had to be pulled down,” a common occurrence in an area marked by decades-old bomb sites full of dangerous debris. When compared to the anesthetized, homogenized, health-and-safety-fied, thoroughly Wetherspooned London of today, Herbert’s childhood world seems almost unimaginably distant, the rotten strata upon which all the Gherkins, Shards, and legions of Pret-a-Manger rest uneasy.

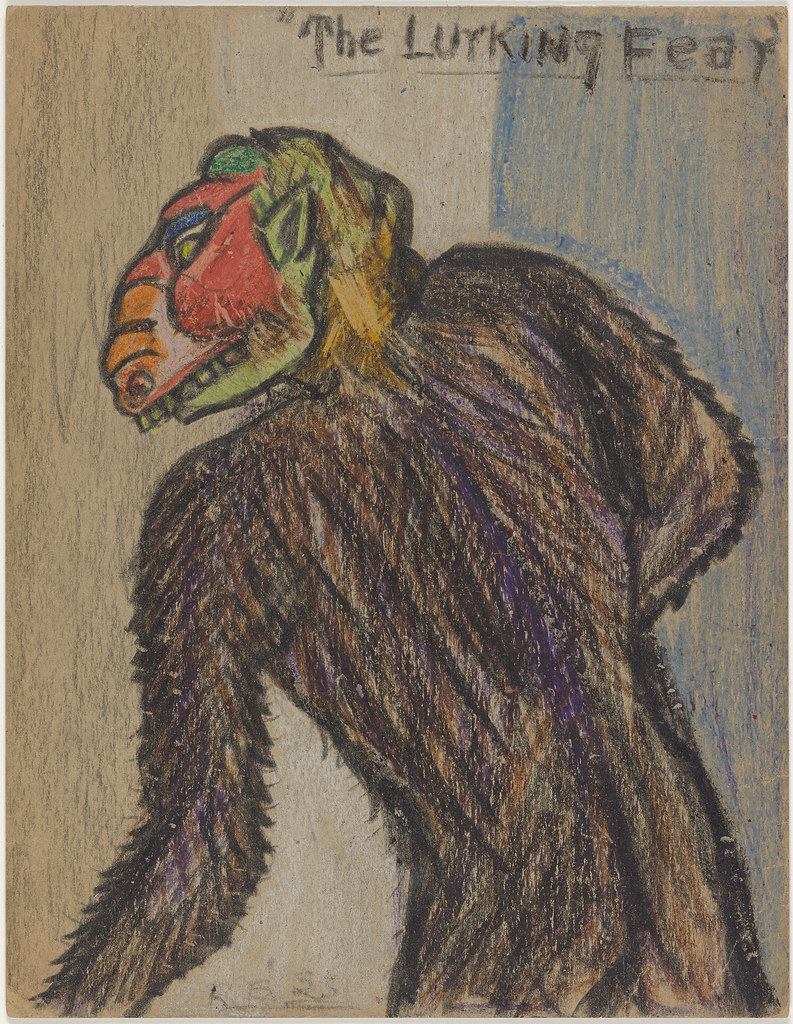

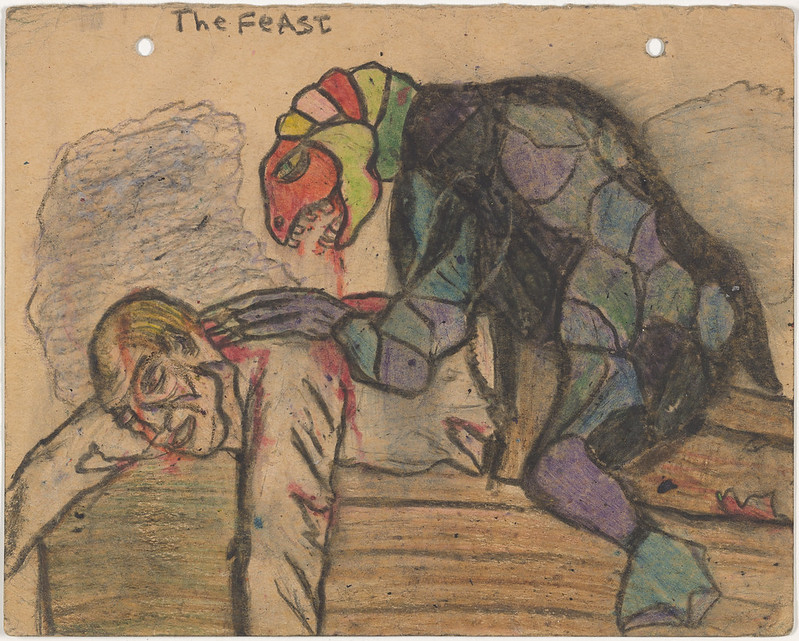

Written over a ten-year span, the Rats trilogy is fairly formulaic plot-wise. Take a London location (the East End, Epping Forest, and the rubble of post-nuclear exchange). Stir in some mutant rats. Add a stolidly generic middle-class man-of-action as the protagonist who urges common sense, morality, and righteous violence in the face of quibbling bureaucratic toffs and effete scientists, wins over the determinedly “modern” young woman (who nevertheless yearns for marriage), and survives the ravening rodent hordes. Salt in occasional vignettes in which characters are introduced (their life histories and often their crudest perversions) in close-third perspective, before having them destroyed in gory Grand Guignol fashion by rats (and, in the third novel, nuclear explosions). The primary storyline is interrupted repeatedly by these deeply personal vignettes, and it is in these sections that Herbert is most effective as an author, demonstrating the character-driven subjectivity and mastery of visceral horror that would develop substantially over his career.

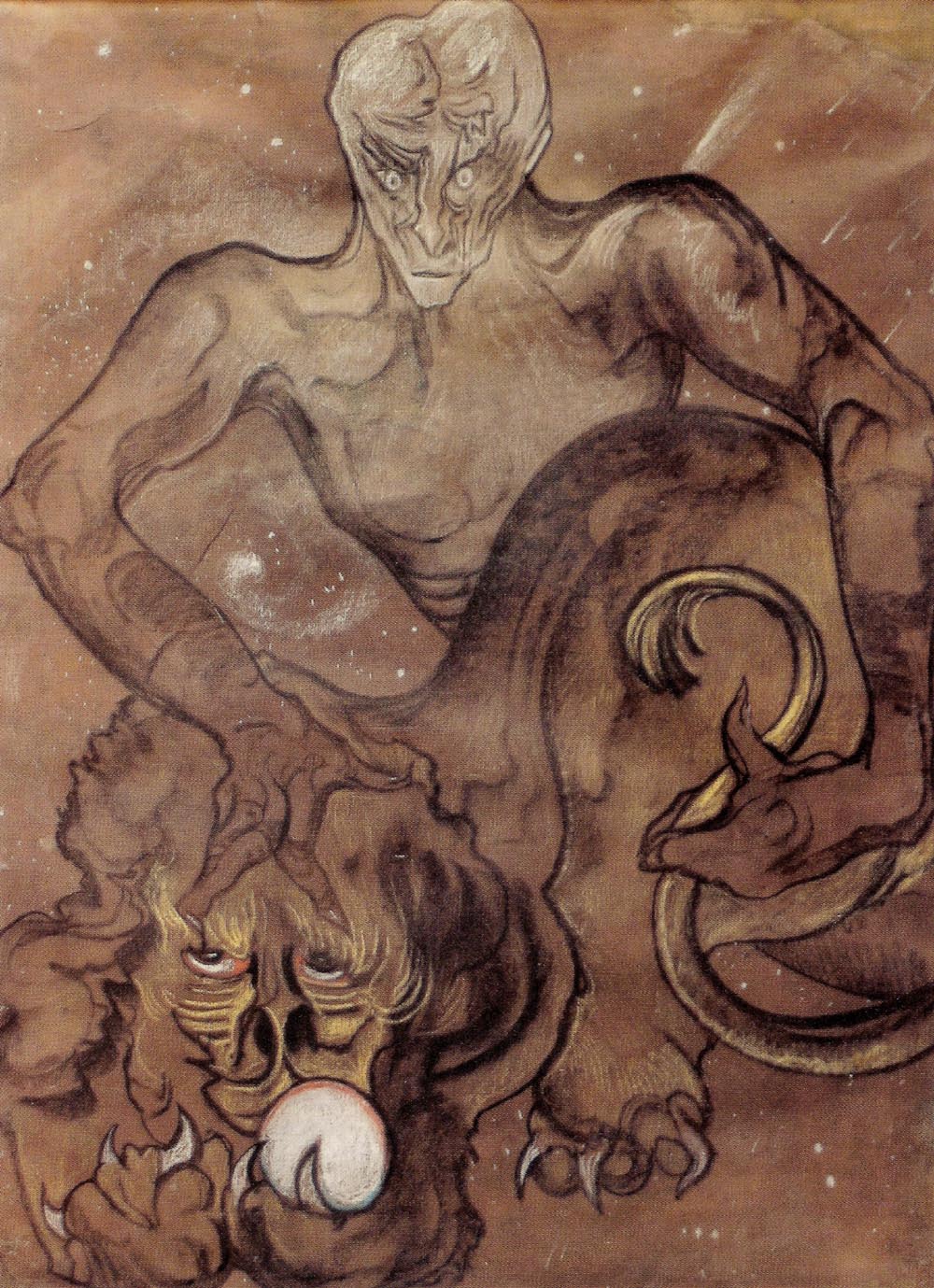

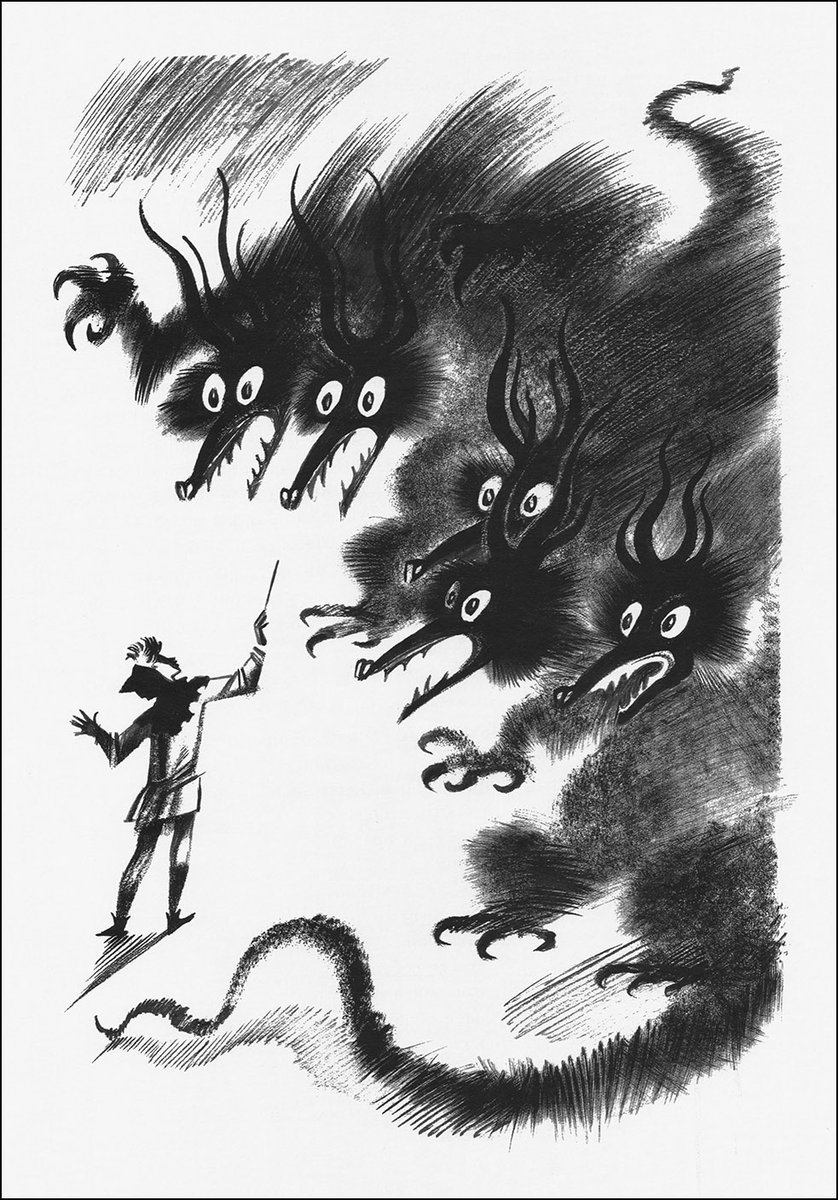

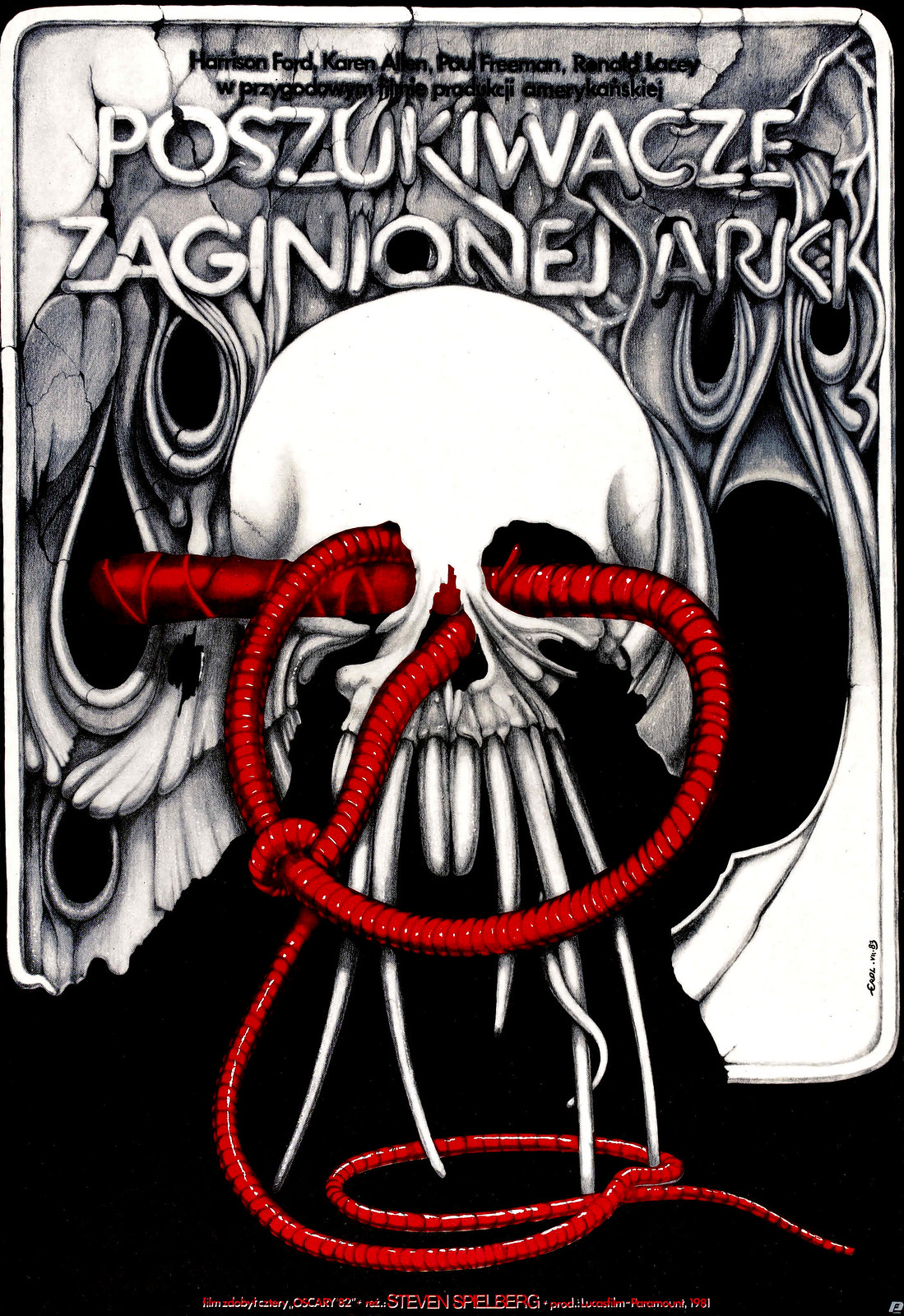

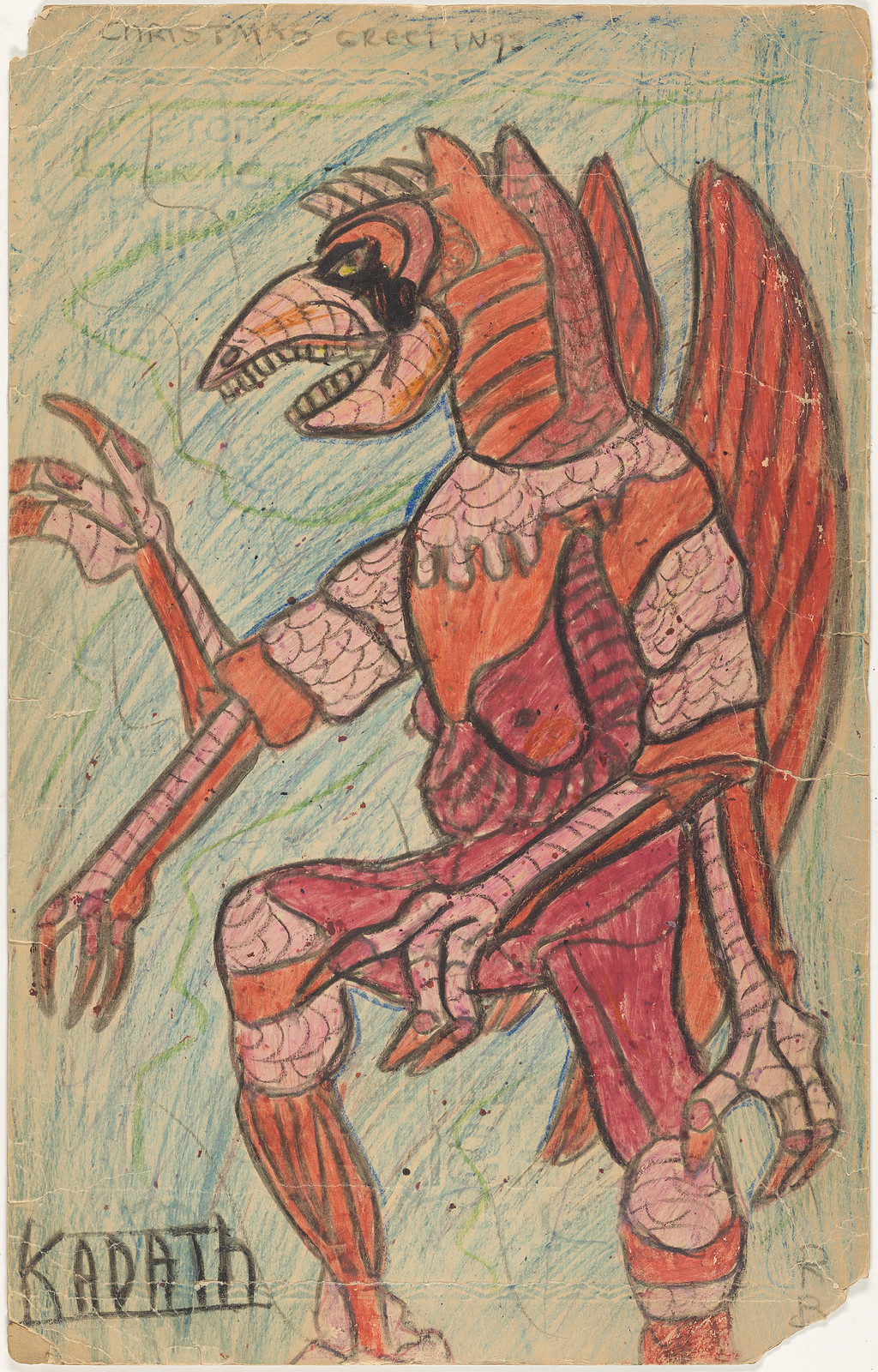

In the first book the protagonist is Harris, a former East End resident returned to work as a school teacher of “art to little bastards whose best work is on lavatory walls.” He is soon made aware of the presence of dog-sized predatory rodents that pursue schoolchildren and various other residents, tearing them to shreds while also carrying a deadly virus that ensures even the slightest bite is fatal. The creatures themselves are mutants, the product of breeding experiments performed by a mad scientist who used a shack in the Docklands as a lab in order to hybridize common black rats with their tropical cousins, irradiated as the result of nuclear testing in the South Pacific. This union results in a much larger, more intelligent, more aggressive species of rat, one that acts cooperatively under the mental command of psychic, two-headed albino rats who serve as overlords.

Various bureaucrats and ministers propose various technocratic solutions to the crisis, like engineered viruses and ultrasonics. The infestation is deemed solved again and again by authorities, only for the monsters to subsequently reemerge and eat the inhabitants of tube stations, cinemas, and schools. By the end, Harris has to take matters into his own hands, dispatching the two-headed rat leader with an axe.

In terms of Herbert’s stated theme of East End neglect, the metaphor is not a particularly subtle one. The residents know there is a problem (urban decay/radioactive rodents), while the government either ignores them or attempts the bare minimum before declaring victory. It’s a pattern painfully analogous to contemporary global catastrophes like the coronavirus pandemic and climate change.

Deeper themes are present in the novel as well, indicative of older prejudices and contexts. The monsters are hybrids, the product of rodent miscegenation and genetic tampering. They are foreign. They operate with a communal intelligence and willing self-sacrifice. The fears of the foreign other, of a caricatured communism and of what the protagonist refers to during a visit to the Royal Shakespeare Theater as the “multi-racial accents that destroyed any hope of atmosphere,” are present throughout the initial novel. They aren’t the predominant themes, but their presence is notable—and somewhat glaring—to the modern reader.

The Rats is an ugly and propulsive book, with scenes of depravity and gore whose power is no less diminished four decades later. While I have never been consumed by rodents (mutant or otherwise), sections like the following seem to capture the flavor (as it were) of the experience:

Rats! His mind screamed the words. Rats eating me alive! God, God help me. Flesh was ripped away from the back of his neck. He couldn’t rise now for the sheer weight of writhing, furry vermin feeding from his body, drinking his blood.

Shivers ran along his spine, to his shocked brain. The dim shadows seemed to float before him, then a redness ran across his vision. It was the redness of unbelievable pain. He couldn’t see any more—the rats had already eaten his eyes.

Respectable reviewers were aghast. Martin Amis’s infamous and vinegary assessment in The Observer set the tone: “By page 20 the rats are slurping up the sleeping baby after the brave bow-wow has fought to the death to save its charge… enough to make a rodent retch, undeniably—and enough to make any human pitch the book aside.” When Herbert went to his local W.H. Smith’s to ask if they had a copy, he was told, “no, and nor were they likely to.”

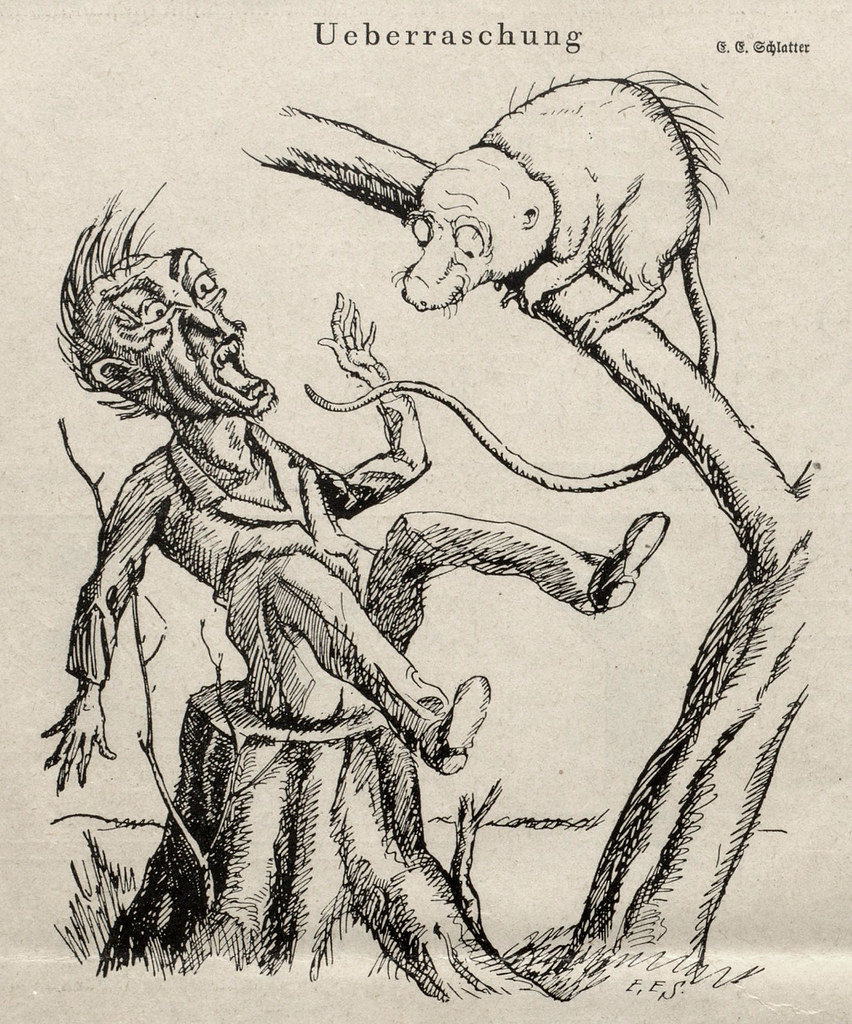

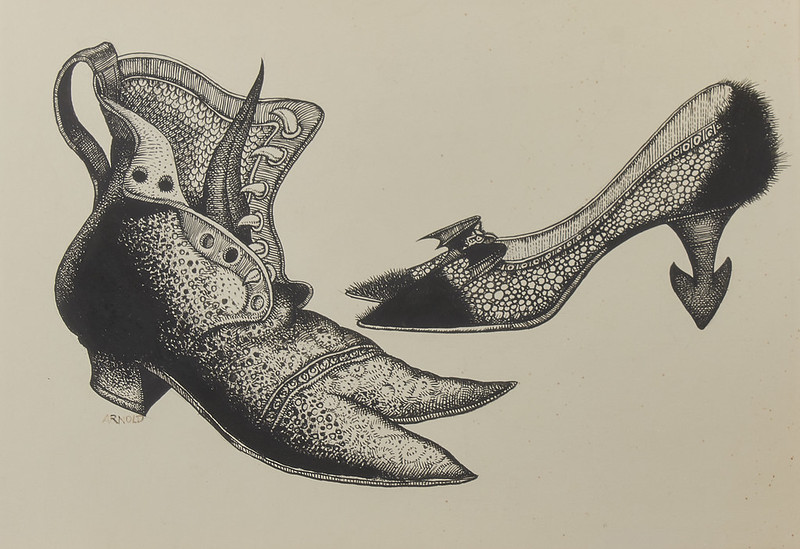

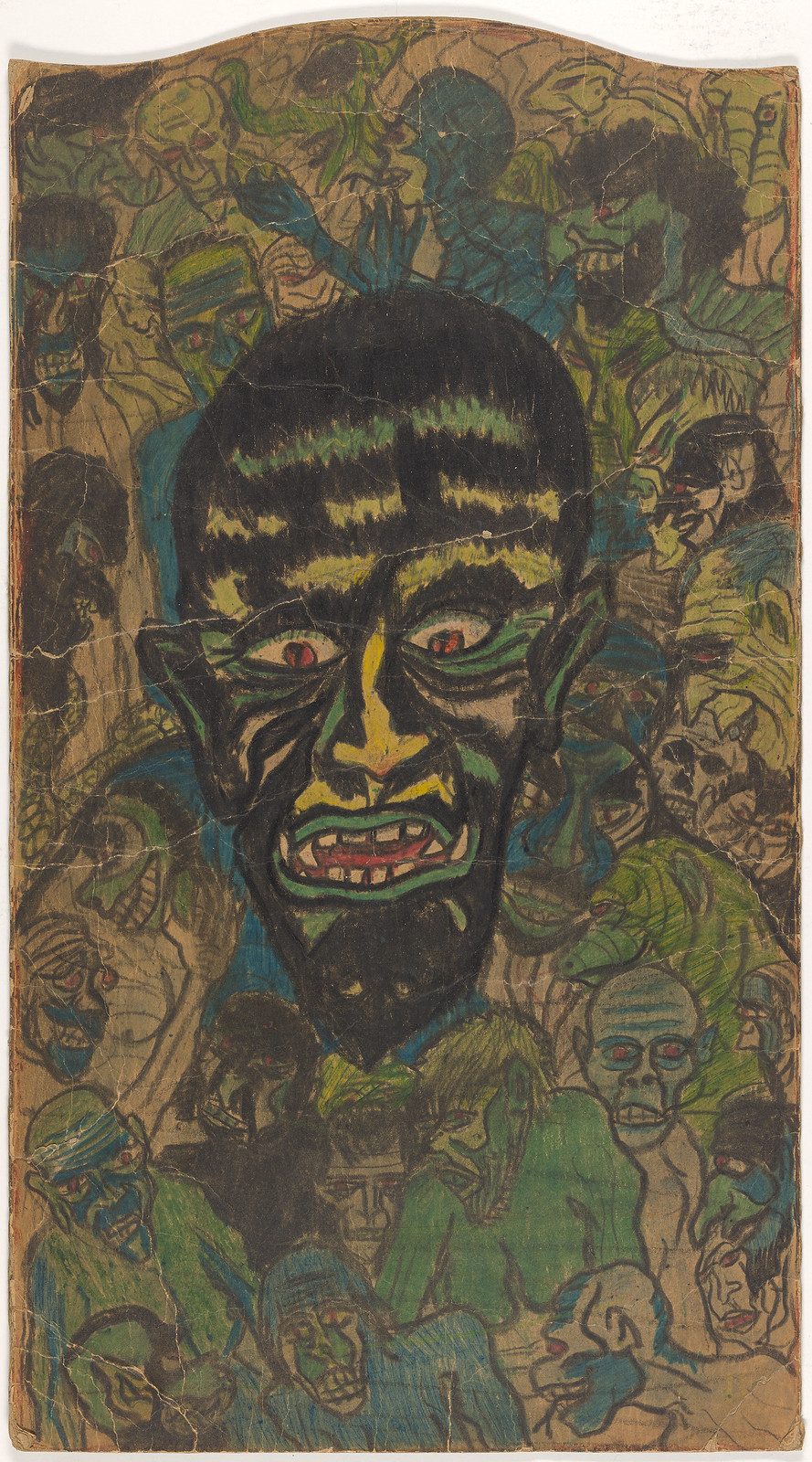

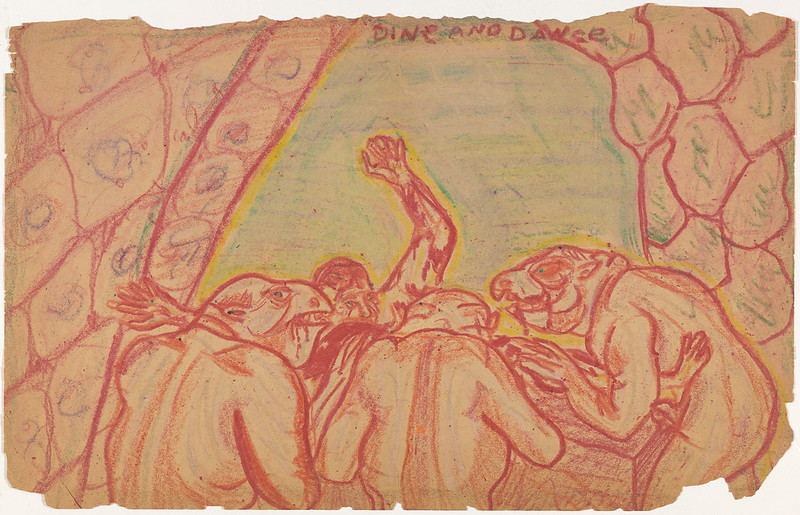

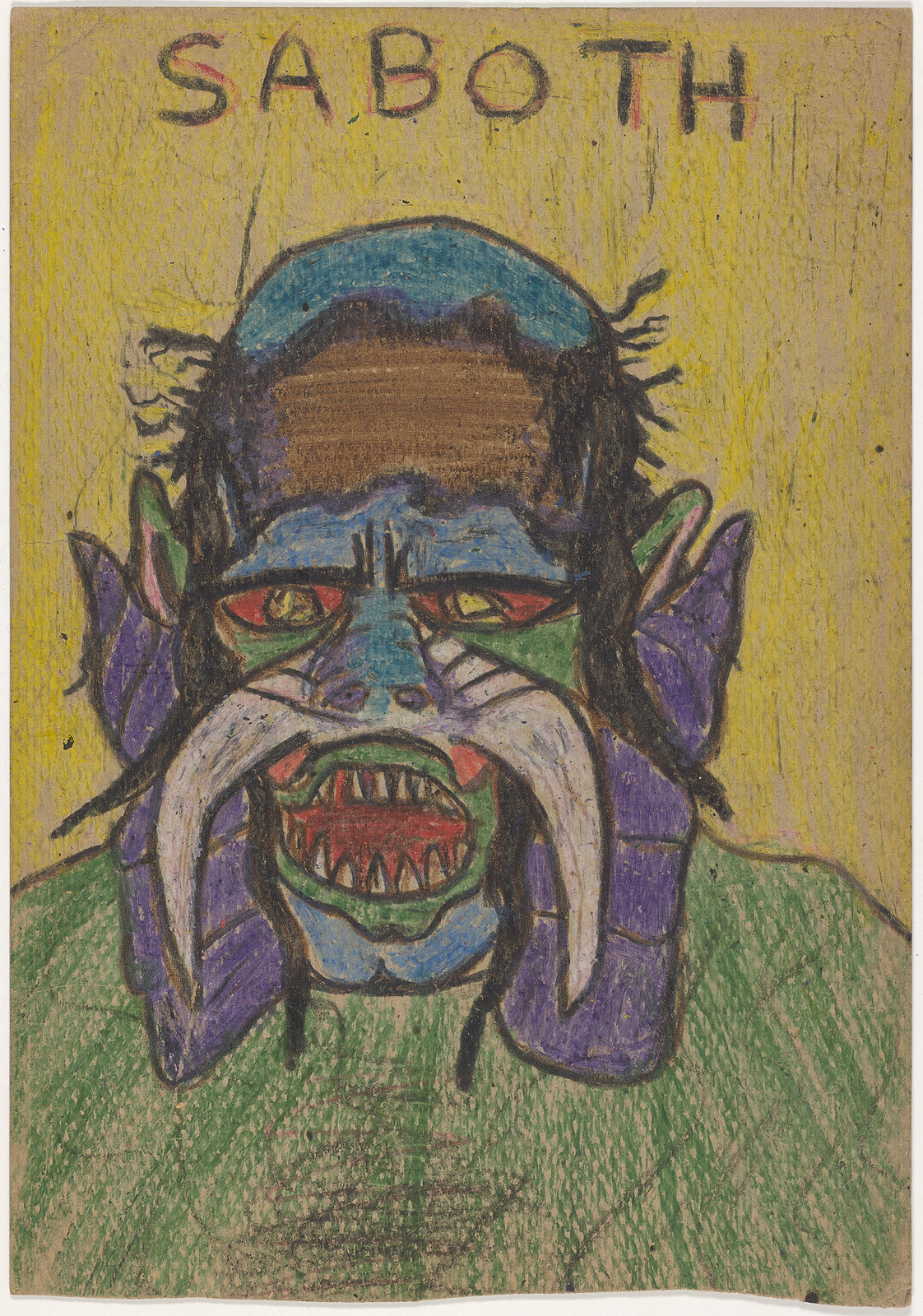

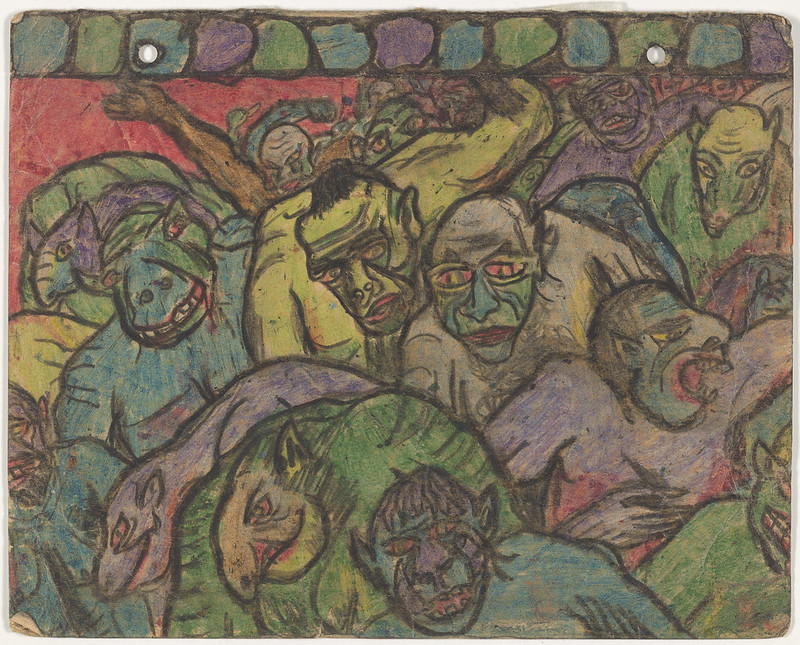

Despite the critical drubbing, the books were an immediate sensation. There is a raw vitality to The Rats, a kind of atavistic anger and verve. At times it has the feel of outsider art, a hint of Henry Darger in the sheer excess of gore coupled with the violations of “good taste” and narrative expectation. In his 1981 book of nonfiction cultural criticism Danse Macabre, Stephen King called it “the literary version of Anarchy in the U.K.”

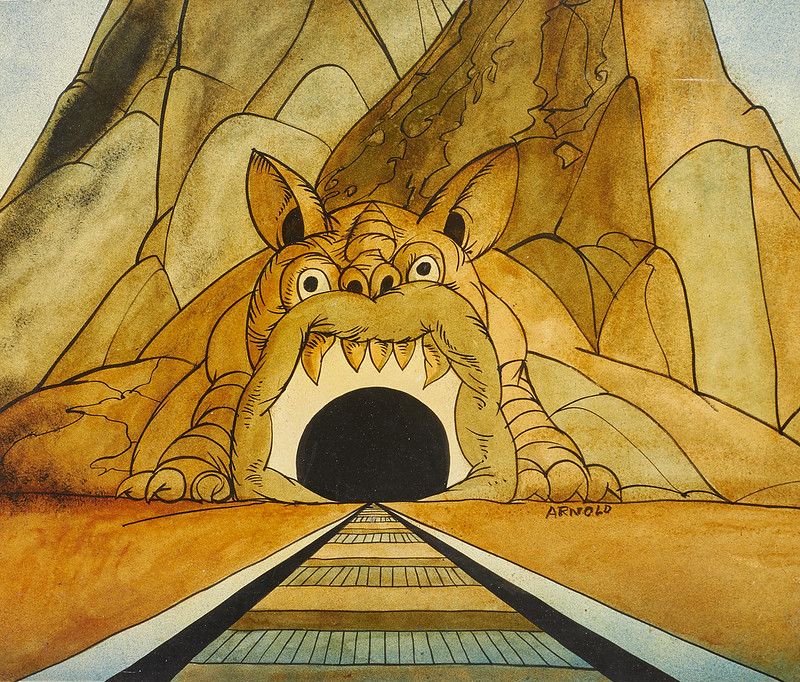

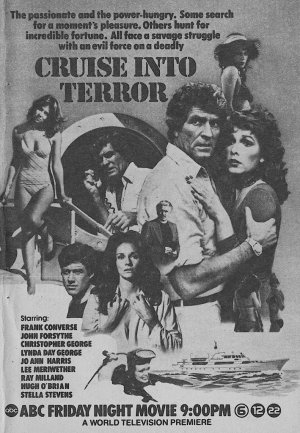

Adaptations of The Rats followed in short order and included a groundbreaking Commodore 64 game, among the first that set out to intentionally frighten the player. The survival horror game won praise for innovations that included the titular creatures eating right through the player’s screen. A 1982 film version was made in Canada as Deadly Eyes, trading the atmospheric decay of London for bland Ontario provincialism. The rats themselves are played by costumed dachshunds, and these unwitting actors were and are the subject of considerable scorn. They look like what they are: plump little pups wriggling beneath latex and fur overcoats. Still, watching these costumed dogs (and puppets in some scenes) in 2020 produces an uncanny valley discomfort, the primal recognition of distorted reality, a sensation that has almost vanished entirely within the weightless wonders of our CGI age.

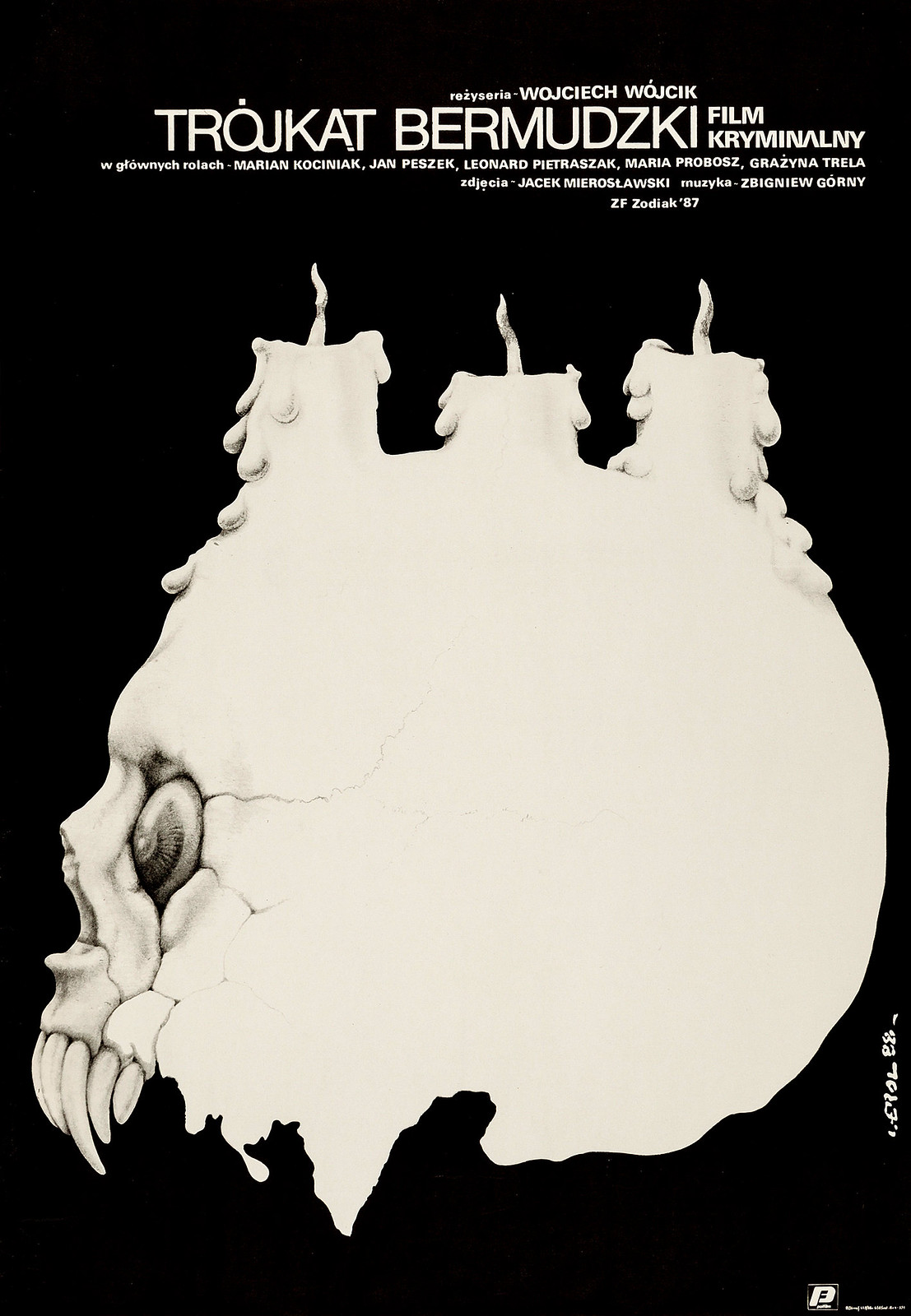

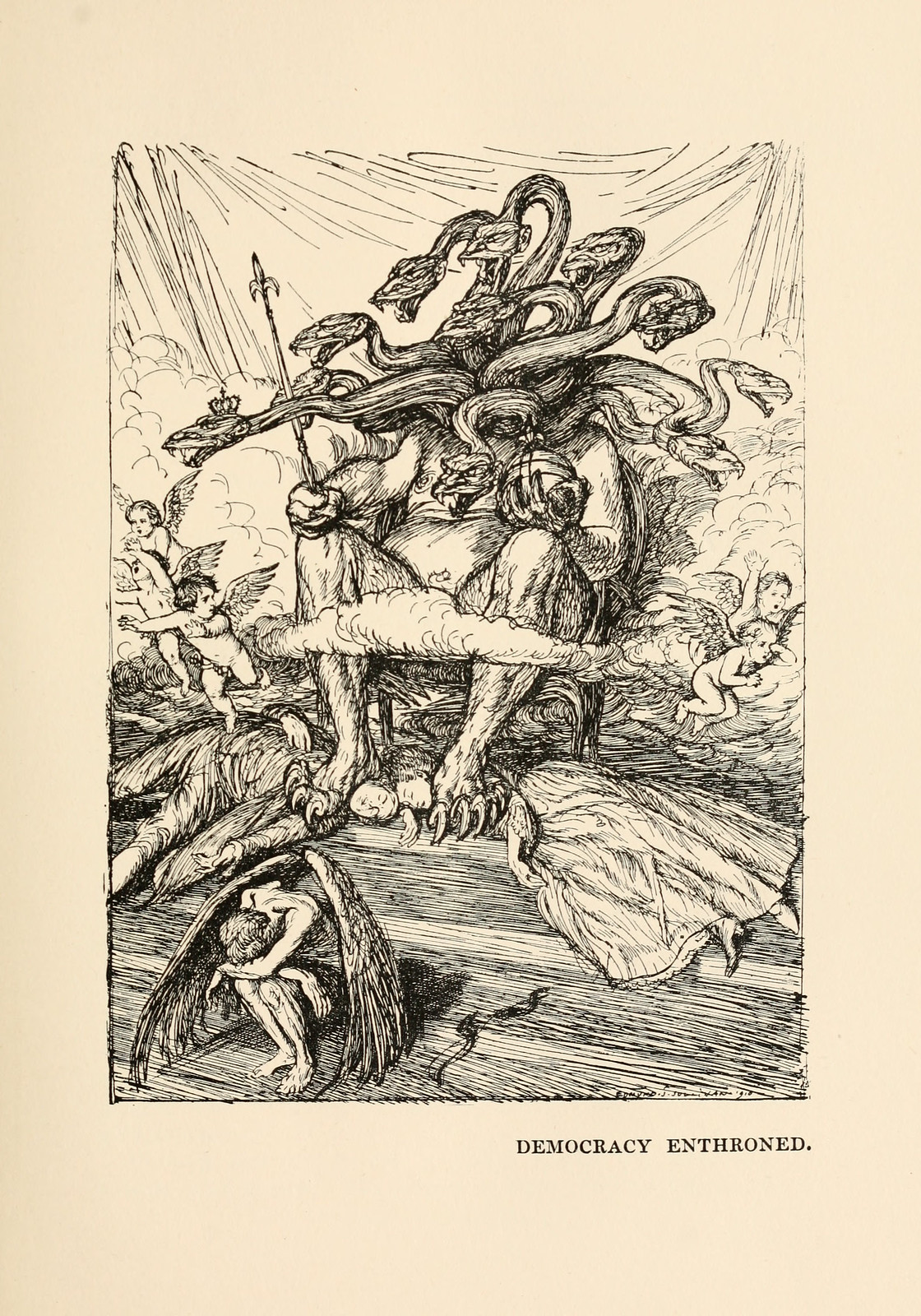

*** The first sequel to The Rats, 1979’s Lair, moves the action from the rotting labyrinth of the Docklands to the green and gentle hills of Greater London’s Epping Forest. Our new muscular protagonist (an exterminator this time) encounters the surviving vermin, while the rats encounter (and eat) various philanderers, exhibitionists, and innocents. Bureaucrats and ministers get in the way of things, problems are thought solved and then, inevitably, the ravaging rodents return. The book ends with rat revolution (reminiscent of Caesar’s ape revolution in the original Planet of the Apes series) as the grotesque two-headed albino psychic overlords are overthrown by the rank-and-file, who then make their stealthy return to London itself.

The first sequel to The Rats, 1979’s Lair, moves the action from the rotting labyrinth of the Docklands to the green and gentle hills of Greater London’s Epping Forest. Our new muscular protagonist (an exterminator this time) encounters the surviving vermin, while the rats encounter (and eat) various philanderers, exhibitionists, and innocents. Bureaucrats and ministers get in the way of things, problems are thought solved and then, inevitably, the ravaging rodents return. The book ends with rat revolution (reminiscent of Caesar’s ape revolution in the original Planet of the Apes series) as the grotesque two-headed albino psychic overlords are overthrown by the rank-and-file, who then make their stealthy return to London itself.

While there is some novelty in the setting of Epping Forest, and Herbert’s depiction therein of a truly English patchwork of bucolic woodlands, raunchy public sex, earnest scouts, depraved flashers, and rotten feudal privilege abutting modern development, Lair is a bit of a letdown. Where The Rats benefits from the sheer audacity and verve of Herbert’s amateur prose, its sequel is a liminal book, in terms of both Herbert’s development as a writer and the period when it was written, the so-called “Winter of Discontent”—which would fuel the rise and electoral triumph of Margaret Thatcher.

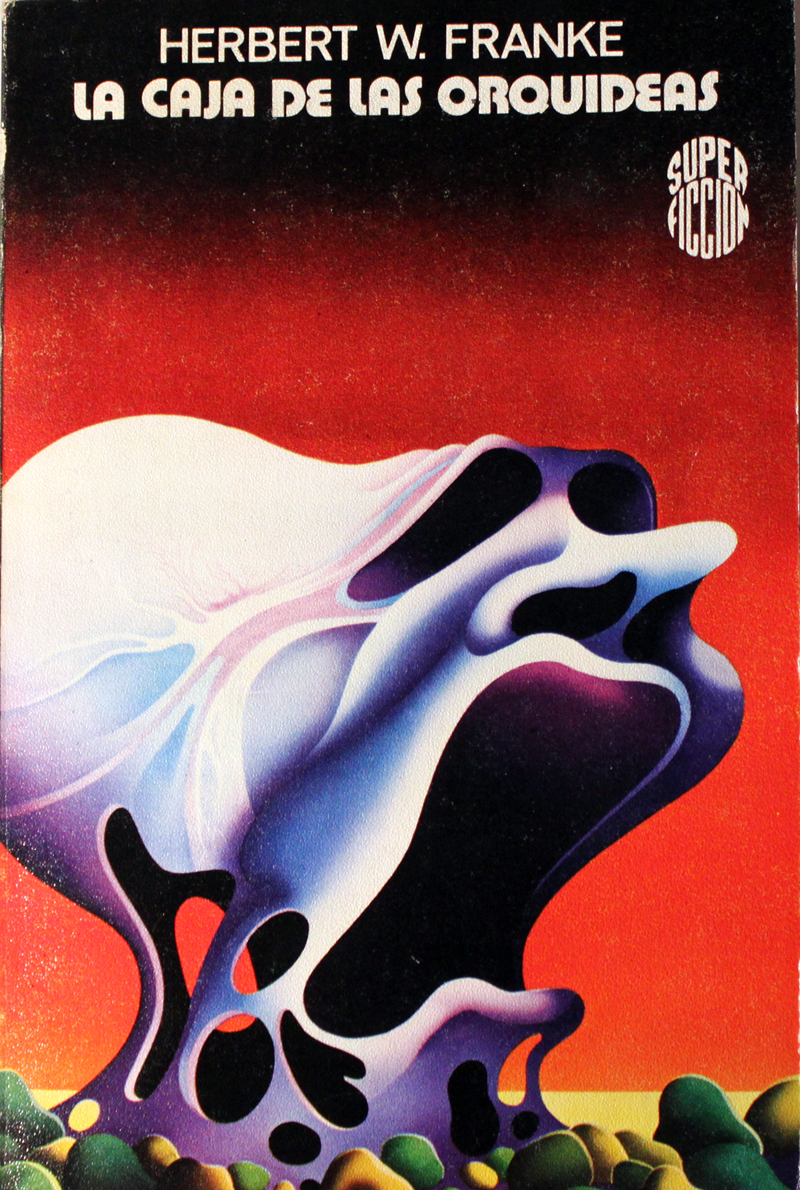

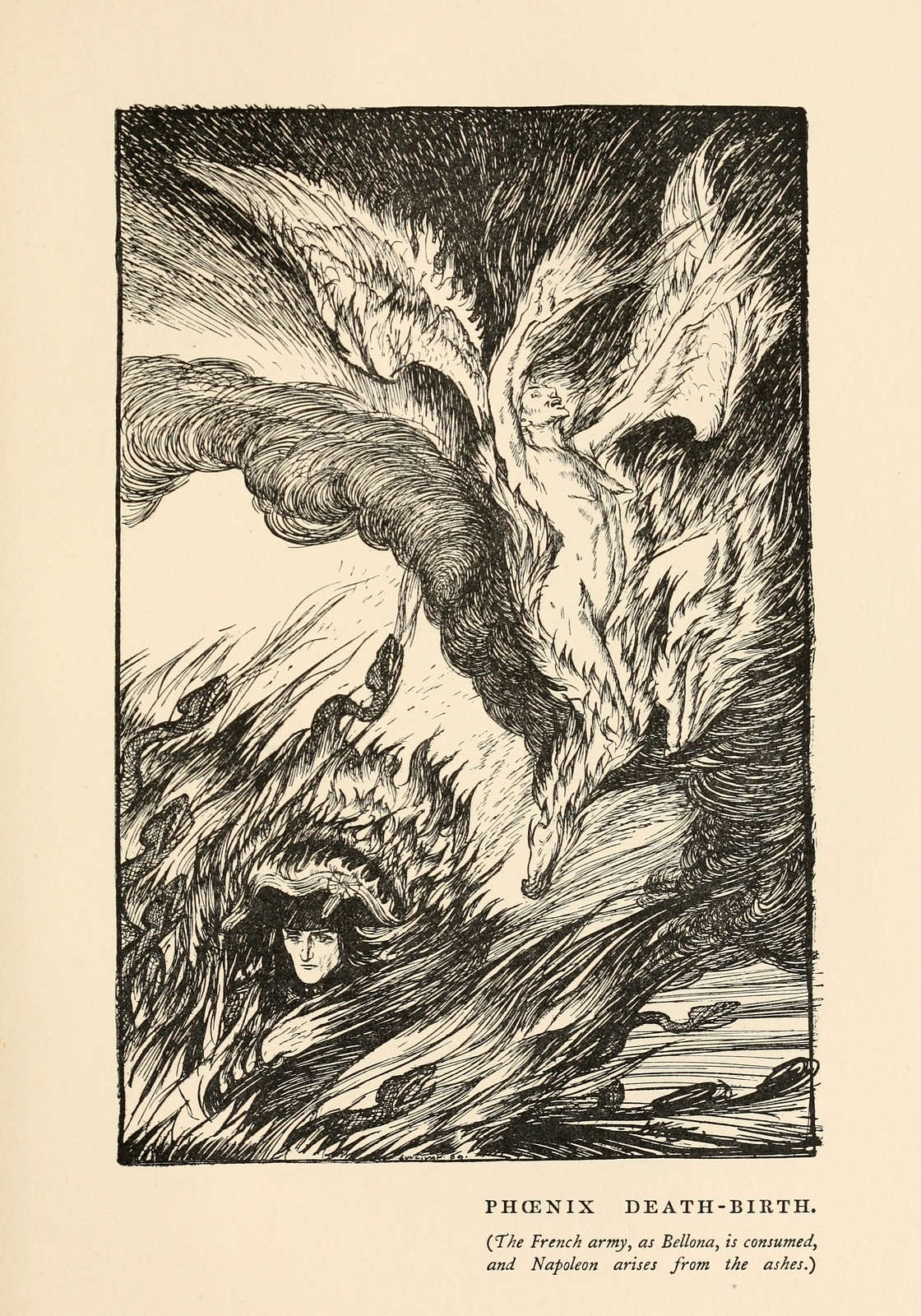

Written five years later, 1984’s Domain, the third book in the trilogy, drips with anger and disdain towards the seismic upheavals convulsing British society, the widening gulf between the machinations of the elite stewards of the neoliberal state and that of the socially integrated individual. Herbert terms this divide in Domain as the “Them” and the “Us.” By this point, the ancient Docklands that had so influenced both the life of James Herbert and the plot of The Rats had been transformed. A firestorm of tax breaks and development subsidies cleared away the rubble and decay (along with venerable neighborhoods and communities), and the new office blocks and skyscrapers of Canary Wharf began their long vertical climb. In Domain, multiple hydrogen bombs are responsible for the razing of the Docklands. In reality, it was Thatcher and the Tory vision of “urban regeneration.”

Domain begins with absolute devastation, with London laid waste by a series of nuclear explosions. Amid the rubble of the city’s ancient roots, a beleaguered group of survivors huddles within a fallout shelter. Among their number is the cold-blooded representative of the government, some hot-headed working-class maintenance staff, and the requisite muscular protagonist, a pilot named Culver. There is bickering, a love-interest, and, of course, a massive horde of waiting, hungry mutants.

Domain begins with absolute devastation, with London laid waste by a series of nuclear explosions. Amid the rubble of the city’s ancient roots, a beleaguered group of survivors huddles within a fallout shelter. Among their number is the cold-blooded representative of the government, some hot-headed working-class maintenance staff, and the requisite muscular protagonist, a pilot named Culver. There is bickering, a love-interest, and, of course, a massive horde of waiting, hungry mutants.

Things quickly fall apart, and the best laid plans of bureaucrats (and rats) go awry. The shelter is breached and the plucky human survivors attempt to find the government’s primary underground headquarters. The bulk of the novel takes place in the ruin of the city itself, one in which the destruction of Herbert’s bombsite-riddled childhood has been spread across the entirety of London. In Domain, the action stays rooted in character, the setting is fully realized, and, like a rock band that knows to save the old hits for the encore, Herbert includes his requisite vignettes in which we meet and sympathize with several characters shortly before their gory demise. While the atavistic blood-rite horror-magic of The Rats is unimpeachable, Domain is far more successful as a novel. When James Herbert reflected on the trilogy in a 2003 interview with the Evening Standard, he agreed, saying that “each one improved on the last. ‘Domain,’ I think validates the first two.”

The key theme in Domain is that of the hubris of the government elite, the “Them” who sought to “manage” a nuclear holocaust safely ensconced within sumptuously appointed fallout shelters (which include royal apartments for “the elite among the elite”). This hubris is punished by a problem they had already declared solved and subsequently ignored: the rats. The consequence of the planner’s plan is a great pit of gnawed, headless bodies, with Thatcher’s mangled corpse assuredly among them. Herbert delights in his own machinations, writing

A failsafe refuge had been constructed for a select few, the rest of the country’s population… left to suffer the full onslaught of the nuclear strike; but the plan had gone terribly wrong, a freak of nature—literally—destroying those escapers just as surely as the nuclear blitz itself…. If there were really a Creator somewhere out there in the blue, he would no doubt be chuckling over mankind’s folly and the retribution paid out to at least some of its leaders.

This indifference and denial of the elite contributes to the bitter humor all throughout. There are multiple scenes where people vaguely remember some nasty business with a new breed of rat having taken place “a few years ago,” the characters emphasizing that thousands of Londoners devoured in a rodent massacre failed to make much of an impression when the victims were the working class residents of the East End.

***While it may not be “fine literature,” reading Herbert’s Rats trilogy in 2020 gives the novels a new layer of subtext that, for all his horrific (and sometimes ridiculous) imaginative powers, the author couldn’t have conceived at the time. Even a revolutionary goresmith like Herbert failed to anticipate the myriad horrors of the neoliberal consensus and the entrenchment of hard-right conservatism: the long half-century of atomization, inequality, loss of empathy, and environmental degradation. Herbert could vividly imagine rats eating London’s impoverished alive by the dozen, but the thought of 130,000 being needlessly sacrificed at the altar of the great god Austerity was too much horror, even for him.

The theme of elite neglect and conscious denial that runs throughout the Rats trilogy has a remarkable resonance with contemporary Western society’s response to the novel coronavirus. Wishful thinking, denial, and elite arrogance have proven no substitute for painful and necessary action. Throughout Herbert’s novels, government officials declare the issue of ravening mutated rodents gnawing their way through the populace “solved”—mission accomplished—after a minimum of effort, simply because it’s easy to say. The parallels are obvious.

Our leadership exacerbates the crises of pandemic through denial, half-measures, and simple nihilistic greed. It’s easy to make a ludicrous lie like “there is no second wave” an official government statement. It’s easy to urge the disposable “us” to “reopen” and return to our “normal life,” without having to make any of the necessary economic or political sacrifices to do so safely. When Boris Johnson’s chief adviser Dominic Cummings boldly breaks curfew or Donald Trump’s Chief of Staff Mark Meadows throws a lavish indoor wedding, the arrogance and disdain is palpable. “We” must sacrifice so “they” can celebrate. As the size of our current COVID-19 wave swells ever larger, with no crest in sight, the true horror lurks at the edges, ready to assert its dominion yet again.

The rats are still here, monstrous as ever. And they’re hungry.

![]() M.L. Schepps lives in federally occupied Portland, where he takes many photos of birds. He spent the last year developing a deep appreciation of Kate Bush while also writing a book about 19th century Chinese immigration and Arctic exploration. Find more of his work at MLSchepps.com.

M.L. Schepps lives in federally occupied Portland, where he takes many photos of birds. He spent the last year developing a deep appreciation of Kate Bush while also writing a book about 19th century Chinese immigration and Arctic exploration. Find more of his work at MLSchepps.com.

Snowbeast

Snowbeast