Marrying the Monster: Apocalyptic and Utopian Impulses in 1950s Sci-Fi Cinema

Pepe Tesoro / May 26, 2021

If you are even mildly interested in science fiction criticism, chances are that you have bumped into Susan Sontag’s 1965 essay “The Imagination of Disaster.” Written at the tail end of the long 1950s golden era of sci-fi film, the text is a bold and keen examination of a genre that wouldn’t receive serious criticism for quite a few years, especially in its cinematic form. Sontag, always motivated to engage with the marginal and seemingly worthless aspects of her culture, was one of the first voices to address the wild popularity of disaster and monster movies during an era that defines the genre to this day.

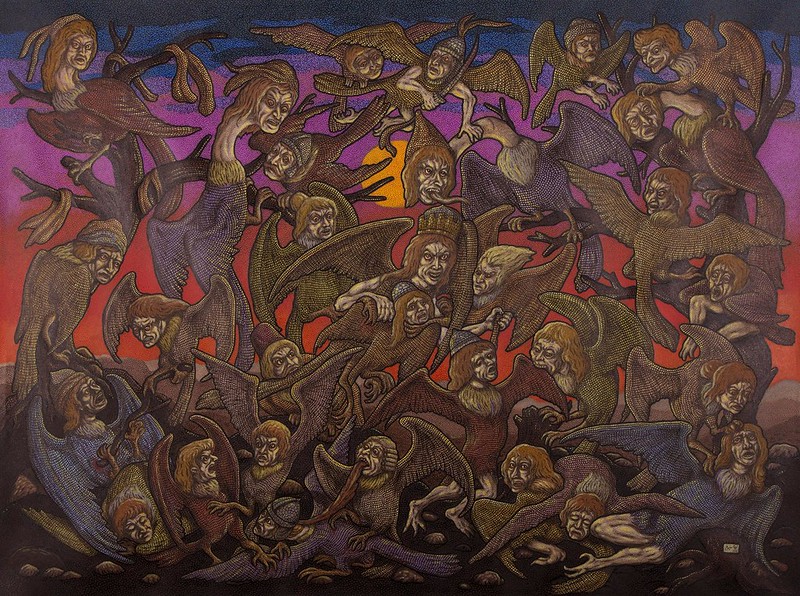

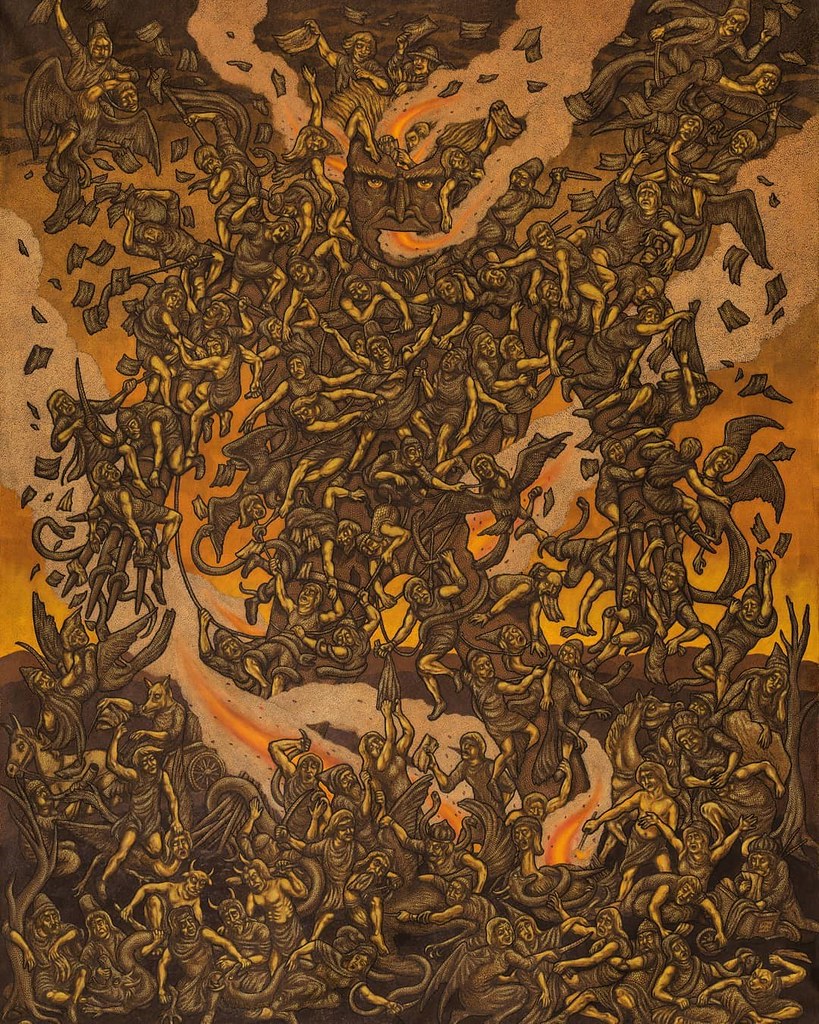

It may seem, though, that Sontag’s central insight was pretty trivial. These movies, for her, represented an expression of a historically specific transformation to a permanent human anxiety towards death, intensified to a qualitatively new level after the horror of concentration camps and the reality of nuclear weapons. This was the result of “the trauma suffered by everyone in the middle of the 20th century,” explains Sontag, “when it became clear that from now on to the end of human history, every person would spend his individual life not only under the threat of individual death, which is certain, but of something almost unsupportable psychologically—collective incineration and extinction which could come any time, virtually without warning.”

It is important to stress, especially today, that the intensification of the fear of extinction and global catastrophe was not just a matter of an increase in potential victims; it was also the new technological sophistication of the means of that destruction. After World War II it became clear not only that humans were able to destroy their own species in a matter of seconds, but also that the new menace of instant extinction was a direct result of human scientific inquiry and the advancement of industry.

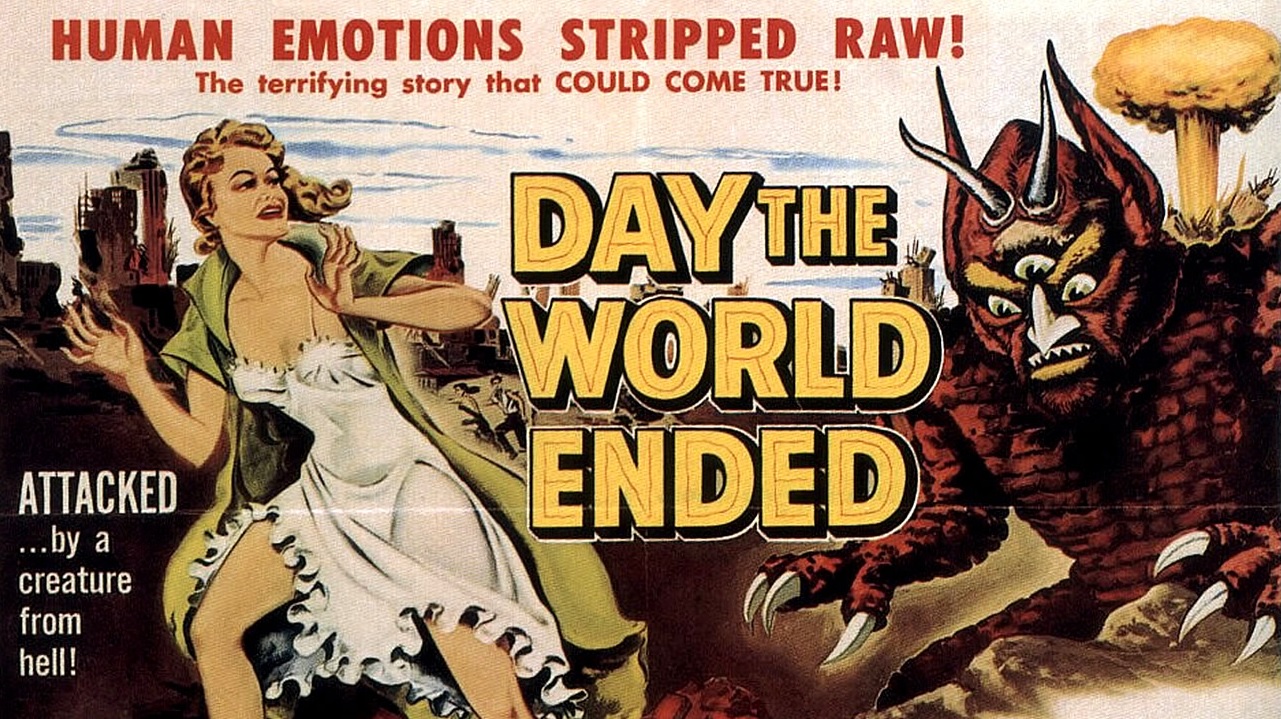

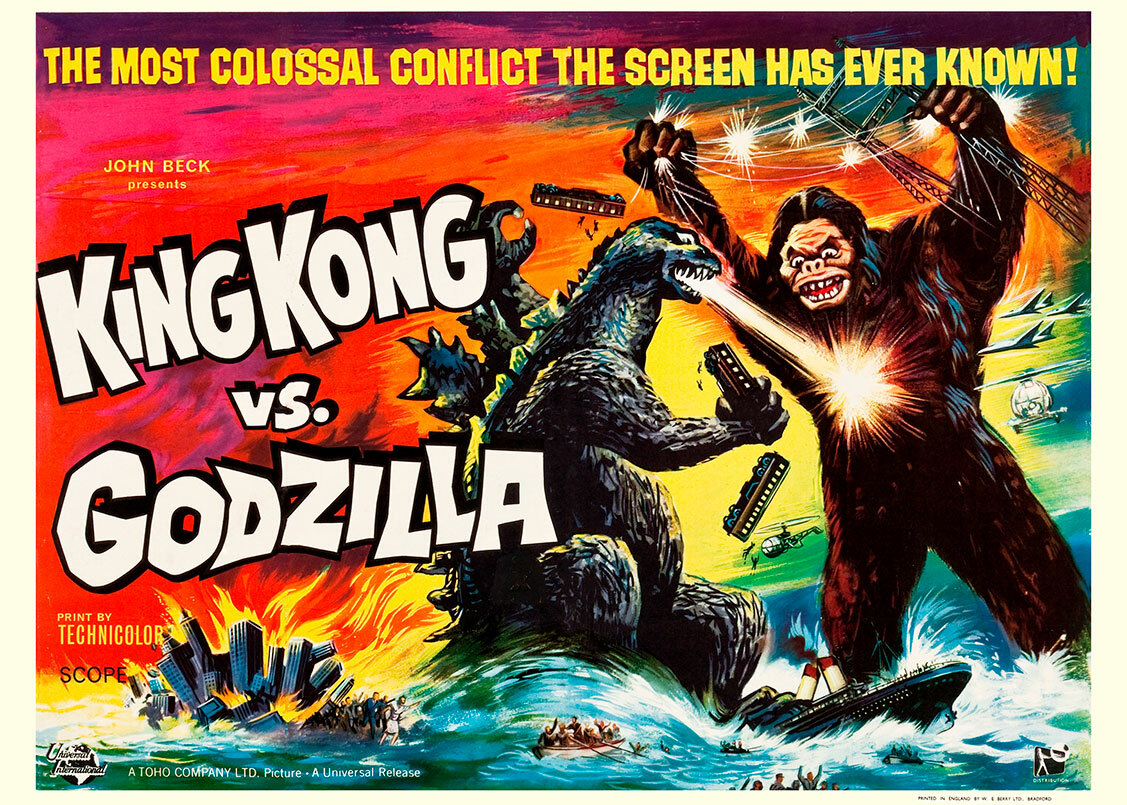

This pretty much encapsulates the ambivalence towards science in 1950s science fiction. In these early genre movies, a scientific advancement or weapon test gone wrong almost always initiates the plot. In The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953), a monstrous prehistoric lizard preserved inside the ice is set free by a series of atomic tests in the Arctic. In an almost identical manner, the giant beast of the quintessential kaiju film Godzilla (1954) is awoken from a dormant state in the bottom of the ocean by the deployment of nuclear weapons. In both of these movies (and in many others, like 1954’s Them! and 1957’s The Amazing Colossal Man), collective destruction is the result of unpredicted consequences of human scientific development that awaken a deadly power that not only surpasses but also often precedes human existence, and which breaks down conventional power structures. Here human responsibility is diluted; there are no discernible culprits and everyone is equally a victim. But there is also the idea of a pre-existing geological determination of human extinction that eerily relates to today’s anxiety about our biological vulnerabilities in the face of environmental collapse.

Godzilla, 1954

There are many themes that can be extracted from 1950s sci-fi movies, from the early postwar tensions of gender dynamics in American society to a sometimes not-so-obvious subtext about racial inequality, to fear of revolution in the face of the decolonization of the Third World and, most prominent, the ghostly menace of communism. There is also a near ubiquitous obsession with depersonalization or, quite literally, “alien”-ation. As Sontag sees it, the mythology of possession has been historically related to animalistic traits, as an overdose of passion and animal instinct, but now it seems that the true fear “is understood as residing in man’s ability to be turned into a machine.” This is the case of productions such as 1960’s Village of the Damned or the fantastic Jack Arnold classic It Came from Outer Space (1953). In both these films (see also 1958’s I Married a Monster from Outer Space), some alien race or entity possesses human hosts or recreates human-like bodies to communicate with us—or to infiltrate our society. This trope (which had the added benefit of being budget-friendly) encapsulated the modern fear of losing human passions and emotions, such as love or solidarity, to the advancement of a cold, sober, and technocratic rationality.

This is, of course, the case of the much-discussed Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956), mostly considered an anti-communist metaphor. But without disregarding the common interpretation around McCarthyism and the Red Scare, the film can also be explained as an expression of greater anxieties about modern dehumanization. As M. Keith Booker puts it, the anti-communist metaphor is available, but “is also perfectly consistent with the content of the film to read the interchangeable pod people as representative of conformist forces within American society itself.”

Countless interpretations are available in these particular visions of catastrophe, but I’d like to focus on the complicity of cinematic spectacle in defusing the threat of catastrophe itself. Sontag herself was wary of science fiction’s fascination with destruction and collective incineration, and appropriately points to the ways in which these films encapsulated the fear of collapse in a satisfactory hour-and-a-half-long narrative, where the good guys always win and the apocalyptic menace is symbolically defeated. Not only could you go on with your life without fearing the bomb, but you could also enjoy the mesmerizing spectacle of the bomb in the glow of a cinema’s film projector. These symbolic solutions more often than not include some form of technological messianism, because even when the problem is caused by science, the threat is almost always defeated by science (Godzilla, 1953’s The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms, 1956’s Earth vs. The Flying Saucers). 1950s science fiction was simultaneously fearful of unleashing scientific advances but also placed its utopian hopes in technology. We enjoy the spectacle of not just crumbling buildings and fiery towers but also of the dissolution of social hierarchies and the incursion of the extraordinary into the monotony of daily life. (The disaster movie genre originates in sci-fi, particularly 1951’s When Worlds Collide and 1953’s The War of the Worlds.) Because at the end, all returns to normal: the scientists save the day, the hero gets the girl, authority is restored.

But these films offer more than mere utopian aspirations focused on technology, or the naturalizing of spectacular violence. The depersonalization inherent in these films often leaves traces of a yearning not so much for technology but for human connection and solidarity. In this sense, I’m personally fascinated by an obscure and low-budget film (Roger Corman’s second sci-fi production) called The Beast with a Million Eyes (1955), in which we are presented with a weird and ghostly ranch, inhabited by a stereotypical patriarchal family, in the middle of the spectral landscapes of the southwestern American desert. After the impact of an extraterrestrial artifact, the ranch is rapidly haunted by the incorporeal presence of an alien spirit that takes control of, first, the animals, and then attempts the same with the humans.

Once again, we are presented with the familiar theme of alien mind control, which turns humans into lifeless machines—no budget needed. But this time the alien encounters a surprising obstacle to its plan: it seems especially difficult to take control of humans when they are bonded by love. In an unexpected speech at the end, the father of the family tells the alien that the secret of human survival is quite simply love and connection, or, as the mother says: “you would never find a human alone.” Other details of the film point to this idea of care and solidarity. For example, the seemingly mute and terrifying servant of the family is revealed in the end to be a war veteran suffering from heavy trauma; the father, a fellow soldier, had taken this traumatized man under his protection from a society that mistakenly deemed him dangerous after feeding him to the machinery of war.

The message is all-too-naive and corny to the modern eye. The question is, though, why do we deem positively portrayed examples of love and affection as something unbearably corny and naive? Speaking about our contemporary cultural sensibility at large and not merely about 1950s science fiction, it seems that today we are totally desensitized to the most extreme images of violence, but the mere representation of unconditional love might make us sick. The technocratic utopianism that runs through 1950s sci-fi cinema has infested not just our fiction about catastrophe, but our narratives of survival and endurance at large. In this sense, a weird oddity like The Beast with a Million Eyes can be seen as a genuine instance where apocalyptic destruction is resisted not by our machines, but by human connection.

These movies don’t necessarily contain a secret revolutionary agenda; we must remain skeptical about the potential of fiction to reconnect to any utopian desire, considering the widely differing receptions and political interpretations that different people bring to the same cultural products. But the overpowering cultural sensibilities that lead us to cynically dismiss messages of connection and solidarity as unsophisticated and credulous, our collective ways of reading fiction and art, can be inverted. I experienced this realization in a recent re-watch of James Cameron’s Aliens (1986). Having seen the movie only once as a teenager, I thought about it as just another militaristic and frenzied spectacle of violence. All I remembered were burning buildings, bullets flying, and the splattering of giant bugs’ acidic blood, so I was pleasantly surprised to discover a compelling tale about teamwork, motherhood, and love, where a bunch of nobodies and outcasts are able to overcome the terror unchained by mindless corporatism through cooperation and quite literally caring for each other.

It goes without saying how pressing and important these attitudes towards violence and solidarity are for us today, in an especially dark and apocalyptic time. I don’t want to indulge in nihilism with an infinite series of examples that offers little to no hope that humanity’s utopian desires and survival instincts can be diverted away from delusional technocracy and towards an aspiration for greater mutual help and cooperation. But if movies about the end of times can be useful at what may be the end of the world as we know it, we may be required to reeducate ourselves and (re)train our sensibilities to forsake the scathing modern cynicism that excretes from this cult-like adoration of technology. We have to search for better answers, better utopias—based on working together and loving one another.

Special thanks to David Sánchez Usanos.

![]() Pepe Tesoro is a philosophy PhD student from Madrid. You can follow him at @pepetesoro.

Pepe Tesoro is a philosophy PhD student from Madrid. You can follow him at @pepetesoro.